Dan Falk in Undark:

While Sutter loves science, he believes there are deep problems with the way science is actually done. He began to notice some of those problems before the Covid-19 pandemic, but it was Covid that brought many of them to the fore. “I was watching, in real time, the erosion of trust in science as an institution,” he said, “and the difficulty scientists had in communicating with the public about a very urgent, very important matter that we were learning about as we were speaking about it.”

While Sutter loves science, he believes there are deep problems with the way science is actually done. He began to notice some of those problems before the Covid-19 pandemic, but it was Covid that brought many of them to the fore. “I was watching, in real time, the erosion of trust in science as an institution,” he said, “and the difficulty scientists had in communicating with the public about a very urgent, very important matter that we were learning about as we were speaking about it.”

“I was watching just one by one,” he continued, as “people stopped trusting science.”

Sutter takes issue with the hyper-competitiveness of science, with peer review, with the journals, with the way scientists interact with the public, with the politicization of science, and more. But his new book, “Rescuing Science: Restoring Trust In an Age of Doubt,’’ published this month by Rowman & Littlefield, is more than a laundry list of grievances — it’s also filled with ideas about how science might be improved.

More here.

Friedrich Nietzsche once wrote: ‘Mankind likes to put questions of origins and beginnings out of its mind.’ With apologies to Nietzsche, the ‘questions of origins and beginnings’ are in fact more controversial and hotly debated. The ongoing Israel-Gaza war has reopened old debates over the circumstances of Israel’s founding and the origins of the Palestinian refugee crisis. Meanwhile, in a speech he gave on the eve of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Vladimir Putin insisted that ‘since time immemorial’ Russia had always included Ukraine, a situation that was disrupted by the establishment of the Soviet Union. And in the US, The New York Times’

Friedrich Nietzsche once wrote: ‘Mankind likes to put questions of origins and beginnings out of its mind.’ With apologies to Nietzsche, the ‘questions of origins and beginnings’ are in fact more controversial and hotly debated. The ongoing Israel-Gaza war has reopened old debates over the circumstances of Israel’s founding and the origins of the Palestinian refugee crisis. Meanwhile, in a speech he gave on the eve of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Vladimir Putin insisted that ‘since time immemorial’ Russia had always included Ukraine, a situation that was disrupted by the establishment of the Soviet Union. And in the US, The New York Times’  Last summer, as I sat waiting for a train in Penn Station, I noticed a figure approaching and trying to get my attention. Keenly aware that I was patronizing an ostensibly public space where the only seats were placed behind gates monitored by security guards, I was eager to part with a few dollars if asked. It took me a moment to register that the woman standing before me, wearing a blue habit and a crucifix around her neck, was asking to borrow my cell phone. She needed to call her elderly father, she said, to tell him that her train would be late, and that she would seek shelter for the night at a convent she had heard of in Boston before continuing her journey. Flooded with a sense of the auspicious, I asked her what her destination was. She said she was heading—as I somehow had felt she would be—to her father’s house on Cape Cod. She named the same town where my in-laws live, to which I, too, was traveling. My husband Jack was picking me up in Providence to drive there, I told her. Would she like a ride?

Last summer, as I sat waiting for a train in Penn Station, I noticed a figure approaching and trying to get my attention. Keenly aware that I was patronizing an ostensibly public space where the only seats were placed behind gates monitored by security guards, I was eager to part with a few dollars if asked. It took me a moment to register that the woman standing before me, wearing a blue habit and a crucifix around her neck, was asking to borrow my cell phone. She needed to call her elderly father, she said, to tell him that her train would be late, and that she would seek shelter for the night at a convent she had heard of in Boston before continuing her journey. Flooded with a sense of the auspicious, I asked her what her destination was. She said she was heading—as I somehow had felt she would be—to her father’s house on Cape Cod. She named the same town where my in-laws live, to which I, too, was traveling. My husband Jack was picking me up in Providence to drive there, I told her. Would she like a ride? AI continues to generate plenty of light and heat. The best models in text and images—now commanding subscriptions and being woven into consumer products—are competing for inches. OpenAI, Google, and Anthropic are all, more or less, neck and neck. It’s no surprise then that AI researchers are looking to push generative models into new territory. As AI requires prodigious amounts of data, one way to forecast where things are going next is to look at what data is widely available online, but still largely untapped. Video, of which there is plenty, is an obvious next step. Indeed, last month, OpenAI previewed

AI continues to generate plenty of light and heat. The best models in text and images—now commanding subscriptions and being woven into consumer products—are competing for inches. OpenAI, Google, and Anthropic are all, more or less, neck and neck. It’s no surprise then that AI researchers are looking to push generative models into new territory. As AI requires prodigious amounts of data, one way to forecast where things are going next is to look at what data is widely available online, but still largely untapped. Video, of which there is plenty, is an obvious next step. Indeed, last month, OpenAI previewed  Lacan collected works by the likes of Duchamp and Picasso, which he displayed proudly in his country home. But to be sure, the most iconic work of his collection, also on view, was Gustave Courbet’s L’Origine du Monde (1866); today, it is owned by the Musée d’Orsay. Famously, Lacan hid this detailed rendering of a vulva behind a sliding wooden door, onto which his friend (and eventual brother-in-law) André Masson painted his own Surrealist rendition. Masson added clouds that drift above an outline of L’Origine’s body, whose curves he recast as hills, her pubic hair resembling a bunch of flowers. L’Origine du Monde almost never leaves d’Orsay. But at the Pompidou-Metz, it no longer hangs alongside other 19th-century works, which often feel prudish in L’Origine’s presence. Instead, the curators have hung it beside more recent representations of vulvas—some of them direct retorts to the famous L’Origine—by the likes of Art & Language, Mircea Cantor, VALIE EXPORT, Victor Man, Betty Tompkins, and Agnès Thurnauer. Deborah de Robertis’s photograph hangs near L’Origine, showing a 2014 performance in which the artist, wearing a gold dress referring to the painting’s gilded frame, squatted in front of the work, spreading her legs wider than Courbet’s model topart her vagina, revealing what she calls “infinity,” or “the origin of the origin,” the depth that Courbet concealed.

Lacan collected works by the likes of Duchamp and Picasso, which he displayed proudly in his country home. But to be sure, the most iconic work of his collection, also on view, was Gustave Courbet’s L’Origine du Monde (1866); today, it is owned by the Musée d’Orsay. Famously, Lacan hid this detailed rendering of a vulva behind a sliding wooden door, onto which his friend (and eventual brother-in-law) André Masson painted his own Surrealist rendition. Masson added clouds that drift above an outline of L’Origine’s body, whose curves he recast as hills, her pubic hair resembling a bunch of flowers. L’Origine du Monde almost never leaves d’Orsay. But at the Pompidou-Metz, it no longer hangs alongside other 19th-century works, which often feel prudish in L’Origine’s presence. Instead, the curators have hung it beside more recent representations of vulvas—some of them direct retorts to the famous L’Origine—by the likes of Art & Language, Mircea Cantor, VALIE EXPORT, Victor Man, Betty Tompkins, and Agnès Thurnauer. Deborah de Robertis’s photograph hangs near L’Origine, showing a 2014 performance in which the artist, wearing a gold dress referring to the painting’s gilded frame, squatted in front of the work, spreading her legs wider than Courbet’s model topart her vagina, revealing what she calls “infinity,” or “the origin of the origin,” the depth that Courbet concealed. In these cases, climate science theory and observations are well aligned. Climate change has increased the frequency of

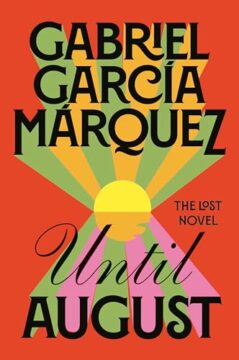

In these cases, climate science theory and observations are well aligned. Climate change has increased the frequency of  What is most jarring is that the story has all the hallmarks of García Márquez; despite its deficiencies, the writing is unmistakably his. At its center is Ana Magdalena Bach, who is a virgin when she marries and remains contentedly faithful to her husband until, at 46, she embarks on a series of explosive one-night stands, a new one each year. She meets the men, all of them strangers, during solo visits to the Caribbean island where her mother is buried. Without fail, every Aug. 16 she lays a bouquet of fresh gladioli on her mother’s grave, clears the weeds that have sprung up around the stone and quickly fills her mother in on the latest family news. Then she gets down to the serious business of finding a partner until morning, when a ferry will take her back to the mainland.

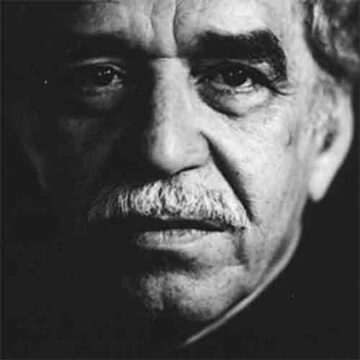

What is most jarring is that the story has all the hallmarks of García Márquez; despite its deficiencies, the writing is unmistakably his. At its center is Ana Magdalena Bach, who is a virgin when she marries and remains contentedly faithful to her husband until, at 46, she embarks on a series of explosive one-night stands, a new one each year. She meets the men, all of them strangers, during solo visits to the Caribbean island where her mother is buried. Without fail, every Aug. 16 she lays a bouquet of fresh gladioli on her mother’s grave, clears the weeds that have sprung up around the stone and quickly fills her mother in on the latest family news. Then she gets down to the serious business of finding a partner until morning, when a ferry will take her back to the mainland. Gabriel García Márquez died ten years ago this April, but people all over the world continue to be stunned, moved, seduced, and transformed by the beauty of his writing and the wildness of his imagination. He is the most translated Spanish-language author of this past century, and in many ways, rightly or wrongly, the made-up Macondo of One Hundred Years of Solitude has come to define the image of Latin America—especially for those of us from the Colombian Caribbean.

Gabriel García Márquez died ten years ago this April, but people all over the world continue to be stunned, moved, seduced, and transformed by the beauty of his writing and the wildness of his imagination. He is the most translated Spanish-language author of this past century, and in many ways, rightly or wrongly, the made-up Macondo of One Hundred Years of Solitude has come to define the image of Latin America—especially for those of us from the Colombian Caribbean. Hollywood rarely shops for film rights at academic presses. Yet if Samuel Moyn’s thought-provoking new book, Liberalism Against Itself, were adapted into a movie, I would recommend making it a courtroom drama.

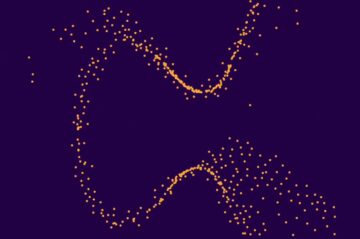

Hollywood rarely shops for film rights at academic presses. Yet if Samuel Moyn’s thought-provoking new book, Liberalism Against Itself, were adapted into a movie, I would recommend making it a courtroom drama. Understanding elliptic curves is a high-stakes endeavor that has been central to math. So in 2022, when a transatlantic collaboration used statistical techniques and artificial intelligence to discover completely unexpected patterns in elliptic curves, it was a welcome, if unexpected, contribution. “It was just a matter of time before machine learning landed on our front doorstep with something interesting,” said

Understanding elliptic curves is a high-stakes endeavor that has been central to math. So in 2022, when a transatlantic collaboration used statistical techniques and artificial intelligence to discover completely unexpected patterns in elliptic curves, it was a welcome, if unexpected, contribution. “It was just a matter of time before machine learning landed on our front doorstep with something interesting,” said  As environmental, social and humanitarian crises escalate, the world can no longer afford two things: first, the costs of economic inequality; and second, the rich. Between 2020 and 2022, the world’s most affluent 1% of people captured nearly twice as much of the new global wealth created as did the other 99% of individuals put together, and in 2019 they emitted as much carbon dioxide as the poorest two-thirds of humanity. In the decade to 2022, the world’s billionaires more than doubled their wealth, to almost US$12 trillion.

As environmental, social and humanitarian crises escalate, the world can no longer afford two things: first, the costs of economic inequality; and second, the rich. Between 2020 and 2022, the world’s most affluent 1% of people captured nearly twice as much of the new global wealth created as did the other 99% of individuals put together, and in 2019 they emitted as much carbon dioxide as the poorest two-thirds of humanity. In the decade to 2022, the world’s billionaires more than doubled their wealth, to almost US$12 trillion. Sam Crane was in the middle of doing Macbeth when the bullets started flying. A veteran of the British stage, Crane was on the verge of playing the lead in the London production of Harry Potter and the Cursed Child when COVID-19 shut down live performances, and by the U.K.’s third lockdown, he was itching for an audience. So instead of playing to a West End crowd, he found himself orating to a smattering of heavily armed lawbreakers inside the video game Grand Theft Auto. “If I could just request that you refrain from killing each other,” he calls out amid the tomorrows and tomorrows. “And don’t kill the actors either!”

Sam Crane was in the middle of doing Macbeth when the bullets started flying. A veteran of the British stage, Crane was on the verge of playing the lead in the London production of Harry Potter and the Cursed Child when COVID-19 shut down live performances, and by the U.K.’s third lockdown, he was itching for an audience. So instead of playing to a West End crowd, he found himself orating to a smattering of heavily armed lawbreakers inside the video game Grand Theft Auto. “If I could just request that you refrain from killing each other,” he calls out amid the tomorrows and tomorrows. “And don’t kill the actors either!” I

I