Melissa Heikkilä in the MIT Technology Review:

I’m stressed and running late, because what do you wear for the rest of eternity?

I’m stressed and running late, because what do you wear for the rest of eternity?

This makes it sound like I’m dying, but it’s the opposite. I am, in a way, about to live forever, thanks to the AI video startup Synthesia. For the past several years, the company has produced AI-generated avatars, but today it launches a new generation, its first to take advantage of the latest advancements in generative AI, and they are more realistic and expressive than anything I’ve ever seen. While today’s release means almost anyone will now be able to make a digital double, on this early April afternoon, before the technology goes public, they’ve agreed to make one of me.

More here.

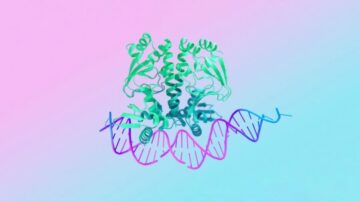

Proteins are biological workhorses. They build our bodies and orchestrate the molecular processes in cells that keep them healthy. They also present a wealth of targets for new medications. From everyday pain relievers to sophisticated cancer immunotherapies, most current drugs interact with a protein. Deciphering protein architectures could lead to new treatments. That was the promise of AlphaFold 2, an AI model from Google DeepMind that predicted how proteins gain their distinctive shapes based on the sequences of their constituent molecules alone. Released in 2020, the tool was a breakthrough half a decade in the making. But proteins don’t work alone. They inhabit an entire cellular universe and often collaborate with other molecular inhabitants like, for example, DNA, the body’s genetic blueprint.

Proteins are biological workhorses. They build our bodies and orchestrate the molecular processes in cells that keep them healthy. They also present a wealth of targets for new medications. From everyday pain relievers to sophisticated cancer immunotherapies, most current drugs interact with a protein. Deciphering protein architectures could lead to new treatments. That was the promise of AlphaFold 2, an AI model from Google DeepMind that predicted how proteins gain their distinctive shapes based on the sequences of their constituent molecules alone. Released in 2020, the tool was a breakthrough half a decade in the making. But proteins don’t work alone. They inhabit an entire cellular universe and often collaborate with other molecular inhabitants like, for example, DNA, the body’s genetic blueprint. As radical as they might seem, calls for limits on wealth are as old as civilization itself. The Hebrew Bible and Torah recognized years during which debts should be cancelled, slaves set free and property redistributed from rich to poor. In classical Greece, Aristotle praised cities that kept wealth inequality in check to enhance political stability. And in 1942, then-US president Franklin D. Roosevelt argued that annual incomes should be capped at the current equivalent of US$480,000.

As radical as they might seem, calls for limits on wealth are as old as civilization itself. The Hebrew Bible and Torah recognized years during which debts should be cancelled, slaves set free and property redistributed from rich to poor. In classical Greece, Aristotle praised cities that kept wealth inequality in check to enhance political stability. And in 1942, then-US president Franklin D. Roosevelt argued that annual incomes should be capped at the current equivalent of US$480,000. Mr. Simons equipped his colleagues with advanced computers to process torrents of data filtered through mathematical models, and turned the four investment funds in his new firm,

Mr. Simons equipped his colleagues with advanced computers to process torrents of data filtered through mathematical models, and turned the four investment funds in his new firm,

Editor-in-chief Sarahanne Field describes herself and her team at the Journal of Trial & Error as wanting to highlight the “ugly side of science — the parts of the process that have gone wrong”.

Editor-in-chief Sarahanne Field describes herself and her team at the Journal of Trial & Error as wanting to highlight the “ugly side of science — the parts of the process that have gone wrong”. Richard Pithouse: Mandela was released from prison on February 11, 1990, suddenly opening up the field of political possibility after a long and exhausting stalemate between the progressive forces, which were largely organized in two groups: the United Democratic Front (UDF) and the trade unions, and the apartheid state. What did Mandela’s release mean to you?

Richard Pithouse: Mandela was released from prison on February 11, 1990, suddenly opening up the field of political possibility after a long and exhausting stalemate between the progressive forces, which were largely organized in two groups: the United Democratic Front (UDF) and the trade unions, and the apartheid state. What did Mandela’s release mean to you? In the years following American independence, many questions would be asked, in different spheres, of what it meant to be a citizen, and

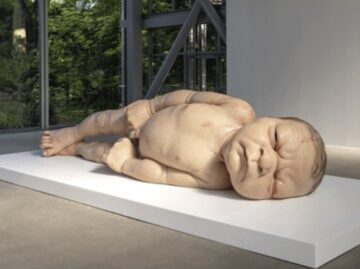

In the years following American independence, many questions would be asked, in different spheres, of what it meant to be a citizen, and  Longevity and eternal youth have frequently been sought after down through the ages, and efforts to keep from dying and fight off age have a long and interesting history.

Longevity and eternal youth have frequently been sought after down through the ages, and efforts to keep from dying and fight off age have a long and interesting history. Butler is soft-spoken and gallant, often sheathed in a trim black blazer or a leather jacket, but, given the slightest encouragement, they turn goofy and sly, almost gratefully. When they were twelve years old, they identified two plausible professional paths: philosopher or clown. In ordinary life, Butler incorporates both.

Butler is soft-spoken and gallant, often sheathed in a trim black blazer or a leather jacket, but, given the slightest encouragement, they turn goofy and sly, almost gratefully. When they were twelve years old, they identified two plausible professional paths: philosopher or clown. In ordinary life, Butler incorporates both.