Otherwise

I got out of bed

on two strong legs.

It might have been

otherwise. I ate

cereal, sweet

milk, ripe, flawless

peach, It might

have been otherwise.

I took the dog uphill

to the birch wood.

All morning I did

the work I love.

At noon I lay down

with my mate. It might

have been otherwise.

We ate dinner together

at a table with silver

candlesticks. It might

have been otherwise.

I slept in a bed

in a room with paintings

on the walls, and

planned another day

just like this day.

But one day, I know,

it will be otherwise.

by Jane Kenyon

from Poetry 180

Random House, 2003

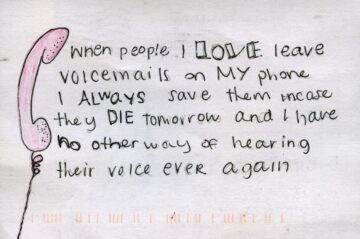

In the fall of 2004, Frank came up with an idea for a project. After he finished delivering documents for the day, he’d drive through the darkened streets of Washington, D.C., with stacks of self-addressed postcards—three thousand in total. At metro stops, he’d approach strangers. “Hi,” he’d say. “I’m Frank. And I collect secrets.” Some people shrugged him off, or told him they didn’t have any secrets. Surely, Frank thought, those people had the best ones. Others were amused, or intrigued. They took cards and, following instructions he’d left next to the address, decorated them, wrote down secrets they’d never told anyone before, and mailed them back to Frank. All the secrets were anonymous.

In the fall of 2004, Frank came up with an idea for a project. After he finished delivering documents for the day, he’d drive through the darkened streets of Washington, D.C., with stacks of self-addressed postcards—three thousand in total. At metro stops, he’d approach strangers. “Hi,” he’d say. “I’m Frank. And I collect secrets.” Some people shrugged him off, or told him they didn’t have any secrets. Surely, Frank thought, those people had the best ones. Others were amused, or intrigued. They took cards and, following instructions he’d left next to the address, decorated them, wrote down secrets they’d never told anyone before, and mailed them back to Frank. All the secrets were anonymous. On Thursday, astronomers who are conducting what they describe as the biggest and most precise survey yet of the history of the universe announced that they might have discovered a major flaw in their understanding of dark energy, the mysterious force that is speeding up the expansion of the cosmos.

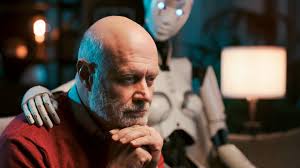

On Thursday, astronomers who are conducting what they describe as the biggest and most precise survey yet of the history of the universe announced that they might have discovered a major flaw in their understanding of dark energy, the mysterious force that is speeding up the expansion of the cosmos. Even though more people will cast a ballot in 2024 than any previous year, the prevailing mood seems more fearful than celebratory. In the words of Darrell M. West, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, the combination of online influence campaigns and artificial intelligence has created a “

Even though more people will cast a ballot in 2024 than any previous year, the prevailing mood seems more fearful than celebratory. In the words of Darrell M. West, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, the combination of online influence campaigns and artificial intelligence has created a “ V

V Simon Rosenberg was right about the congressional elections of 2022. All the conventional wisdom — the polls, the punditry, the fretting by fellow Democrats — revolved around the expectation of a big red wave and a Democratic wipeout. He disagreed. Democrats would surprise everyone, he said again and again: There would be no red wave. He was correct, of course, as he is quick to remind anyone listening. These days, Mr. Rosenberg, 60, a Democratic strategist and consultant who dates his first involvement in presidential campaigns to Michael Dukakis, the Democratic presidential candidate in 1988, is again pushing back against the polls and punditry and the Democratic doom and gloom. This time, he is predicting that President Biden will defeat Donald J. Trump in November.

Simon Rosenberg was right about the congressional elections of 2022. All the conventional wisdom — the polls, the punditry, the fretting by fellow Democrats — revolved around the expectation of a big red wave and a Democratic wipeout. He disagreed. Democrats would surprise everyone, he said again and again: There would be no red wave. He was correct, of course, as he is quick to remind anyone listening. These days, Mr. Rosenberg, 60, a Democratic strategist and consultant who dates his first involvement in presidential campaigns to Michael Dukakis, the Democratic presidential candidate in 1988, is again pushing back against the polls and punditry and the Democratic doom and gloom. This time, he is predicting that President Biden will defeat Donald J. Trump in November. In McCarthy’s novels, people commit terrible acts—necrophilia, infanticide, cannibalism—and often with reason. His villains are symbols of that dark reason: the trio of swampland marauders in Outer Dark (1968), the dream-curdling scalp-hunter in Blood Meridian, the frigid bounty hunter stalking No Country. In The Passenger and Stella Maris, McCarthy tops this rap sheet with his worst crime yet: nuclear Armageddon. And the perp is one of American history’s finest minds, the porkpie-hatted architect of the atomic bomb, J. Robert Oppenheimer.

In McCarthy’s novels, people commit terrible acts—necrophilia, infanticide, cannibalism—and often with reason. His villains are symbols of that dark reason: the trio of swampland marauders in Outer Dark (1968), the dream-curdling scalp-hunter in Blood Meridian, the frigid bounty hunter stalking No Country. In The Passenger and Stella Maris, McCarthy tops this rap sheet with his worst crime yet: nuclear Armageddon. And the perp is one of American history’s finest minds, the porkpie-hatted architect of the atomic bomb, J. Robert Oppenheimer. H

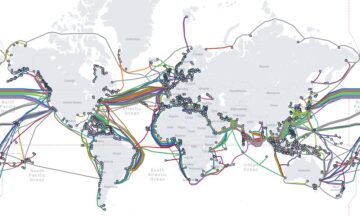

H Have you ever wondered how an email sent from New York arrives in Sydney in mere seconds, or how you can video chat with someone on the other side of the globe with barely a hint of delay? Behind these everyday miracles lies an unseen, sprawling web of undersea cables, quietly powering the instant global communications that people have come to rely on.

Have you ever wondered how an email sent from New York arrives in Sydney in mere seconds, or how you can video chat with someone on the other side of the globe with barely a hint of delay? Behind these everyday miracles lies an unseen, sprawling web of undersea cables, quietly powering the instant global communications that people have come to rely on. But single expressions are merely “pieces of a man,” as Adam Shatz, quoting Gil Scott-Heron, observes in The Rebel’s Clinic: The Revolutionary Lives of Frantz Fanon. In this timely and engaging new book—the first full-length biography in English since David Macey’s in 2000—Shatz restores a sense of wholeness to Fanon’s life and work. The unifying pursuit of Fanon’s life, Shatz argues, was the “disalienation” of those suffering from racial and colonial oppression—a project at once individual and social, clinical as well as political. For Fanon, Shatz concludes, this was the end goal of psychiatry as a practice of freedom.

But single expressions are merely “pieces of a man,” as Adam Shatz, quoting Gil Scott-Heron, observes in The Rebel’s Clinic: The Revolutionary Lives of Frantz Fanon. In this timely and engaging new book—the first full-length biography in English since David Macey’s in 2000—Shatz restores a sense of wholeness to Fanon’s life and work. The unifying pursuit of Fanon’s life, Shatz argues, was the “disalienation” of those suffering from racial and colonial oppression—a project at once individual and social, clinical as well as political. For Fanon, Shatz concludes, this was the end goal of psychiatry as a practice of freedom. Beyoncé

Beyoncé Heavy industry is one of the most stubbornly difficult areas of the economy to decarbonize. But new research suggests emissions could be reduced by up to 85 percent globally using a mixture of tried-and-tested and upcoming technologies. While much of the climate debate focuses on areas like electricity, vehicle emissions, and aviation, a huge fraction of carbon emissions comes from hidden industrial processes. In 2022, the sector—which includes things like chemicals, iron and steel, and cement—accounted for a quarter of the world’s emissions,

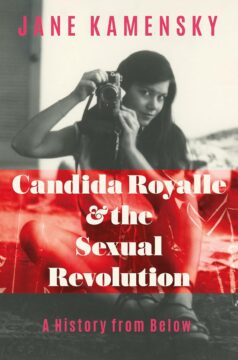

Heavy industry is one of the most stubbornly difficult areas of the economy to decarbonize. But new research suggests emissions could be reduced by up to 85 percent globally using a mixture of tried-and-tested and upcoming technologies. While much of the climate debate focuses on areas like electricity, vehicle emissions, and aviation, a huge fraction of carbon emissions comes from hidden industrial processes. In 2022, the sector—which includes things like chemicals, iron and steel, and cement—accounted for a quarter of the world’s emissions,  “DID PORN KILL feminism?” asked Amia Srinivasan in her widely read book The Right to Sex (2021). In the internet age, it sure can look that way. As Srinivasan pointed out, top commercial porn sites host billions of visitors every month. Today’s college students grew up with those sites just a click away. Many had their first sexual experiences in front of a computer screen. When she talked with her own college students, she saw the consequences:

“DID PORN KILL feminism?” asked Amia Srinivasan in her widely read book The Right to Sex (2021). In the internet age, it sure can look that way. As Srinivasan pointed out, top commercial porn sites host billions of visitors every month. Today’s college students grew up with those sites just a click away. Many had their first sexual experiences in front of a computer screen. When she talked with her own college students, she saw the consequences: Best Bees is one of the many companies carving out a niche in a commercial landscape increasingly focused on advertising environmental responsibility, pushed by both customer demand and regulatory requirements. Testing environmental DNA, which allows data to be gathered from the tiny pieces of skin, scales, and slime that species shed as they move through the world, has been framed as a cheap and efficient way to understand a corporation’s impact.

Best Bees is one of the many companies carving out a niche in a commercial landscape increasingly focused on advertising environmental responsibility, pushed by both customer demand and regulatory requirements. Testing environmental DNA, which allows data to be gathered from the tiny pieces of skin, scales, and slime that species shed as they move through the world, has been framed as a cheap and efficient way to understand a corporation’s impact.