Category: Recommended Reading

Tony Lo Bianco (1936 – 2024) Actor

Self-understanding of self-organization

The Brainstem Fine-Tunes Inflammation Throughout the Body

Esther Landhuis in Quanta Magazine:

Last month, researchers discovered cells in the brainstem that regulate inflammation throughout the body. In response to an injury, these nerve cells not only sense inflammatory molecules, but also dial their circulating levels up and down to keep infections from harming healthy tissues. The discovery adds control of the immune system to the brainstem’s core functions — a list that also includes monitoring heart rate, breathing and aspects of taste — and suggests new potential targets for treating inflammatory disorders like arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease.

Last month, researchers discovered cells in the brainstem that regulate inflammation throughout the body. In response to an injury, these nerve cells not only sense inflammatory molecules, but also dial their circulating levels up and down to keep infections from harming healthy tissues. The discovery adds control of the immune system to the brainstem’s core functions — a list that also includes monitoring heart rate, breathing and aspects of taste — and suggests new potential targets for treating inflammatory disorders like arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease.

During an intense workout or high-stakes exam, your brain can sense the spike in your heart rate and help restore a normal rhythm. Likewise, the brain can help stabilize your blood pressure by triggering chemical signals that widen or constrict blood vessels. Such feats often go unnoticed, but they illustrate a fundamental concept of physiology known as homeostasis — the capacity of organisms to keep their internal systems working smoothly and stably amid shifting circumstances. Now, in a paper published on May 1 in Nature, researchers describe how homeostatic control extends even to the sprawl of cells and tissues that comprise our immune system. The team applied a clever genetic approach in mice to identify cells in the brainstem that adjust immune reactions to pathogens and other outside triggers. These neurons operate like a “volume controller” that keeps the animals’ inflammatory responses within a physiological range, said paper author Hao Jin, a neuroimmunologist at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

More here.

Edward Stone (1936 – 2024) Physicist

Sunday Poem

How to Be a Poet

(to remind myself)

i

Make a place to sit down.

Sit down. Be quiet.

You must depend upon

affection, reading, knowledge,

skill—more of each

than you have—inspiration,

work, growing older, patience,

for patience joins time

to eternity. Any readers

who like your poems,

doubt their judgment.

ii

Breathe with unconditional breath

the unconditioned air.

Shun electric wire.

Communicate slowly. Live

a three-dimensioned life;

stay away from screens.

Stay away from anything

that obscures the place it is in.

There are no unsacred places;

there are only sacred places

and desecrated places.

iii

Accept what comes from silence.

Make the best you can of it.

Of the little words that come

out of the silence, like prayers

prayed back to the one who prays,

make a poem that does not disturb

the silence from which it came.

by Wendell Berry

from The Selected Poems of Wendell Berry

Saturday, June 15, 2024

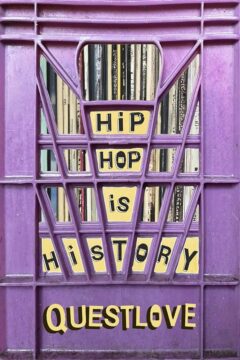

‘Hip-Hop Is History’ By Questlove

Dorian Lynskey at The Guardian:

Hip-hop officially turned 50 last year. It is generally accepted that it was born on 11 August 1973, when 18-year-old DJ Kool Herc first cut up breakbeats at a party in the Bronx and his friend Coke La Rock rapped along, but this DJ-driven art form, which evolved parallel to disco, took another six years to spawn its first hit single, the Sugarhill Gang’s Rapper’s Delight. The star MCs emerged in its second decade, each one redrawing the bounds of the possible. Run-DMC stripped it down, then Public Enemy blew it up. De La Soul made it friendly, Kool Keith made it freaky, NWA made it outrageous, and so on. Always changing, always expanding.

Hip-hop officially turned 50 last year. It is generally accepted that it was born on 11 August 1973, when 18-year-old DJ Kool Herc first cut up breakbeats at a party in the Bronx and his friend Coke La Rock rapped along, but this DJ-driven art form, which evolved parallel to disco, took another six years to spawn its first hit single, the Sugarhill Gang’s Rapper’s Delight. The star MCs emerged in its second decade, each one redrawing the bounds of the possible. Run-DMC stripped it down, then Public Enemy blew it up. De La Soul made it friendly, Kool Keith made it freaky, NWA made it outrageous, and so on. Always changing, always expanding.

Nobody knows more about hip-hop, and perhaps popular music in general, than Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson. Still drumming with the Roots, the Philadelphia hip-hop crew that have been Jimmy Fallon’s TV house band since 2009, he is also the Oscar-winning director of Summer of Soul, a prolific author, podcaster and DJ, and the man tasked with herding cats for the Grammys’ salute to hip-hop at 50.

more here.

Liberalism As a Way of Life

Damon Linker interviews Alexandre Lefebvre in Notes from the Middle Ground:

DL: Thanks for being here, Alex. One reason I enjoyed your book so much is that it’s such a departure from the tired, bone-dry proceduralism of the Rawlsian liberalism I imbibed in graduate school during the 1990s. Liberalism, we were taught, is “political, not metaphysical.” It isn’t a “comprehensive view” of the good. Rather, it shows how people holding such comprehensive views can come together and do politics without reference to such bigger, deeper, or higher commitments. Your account of the liberal tradition is very different and maintains that liberalism, rightly understood, is a “way of life,” which sounds pretty comprehensive to me. Would you say that’s a fair characterization of liberalism?

AL: Thanks for the invitation, Damon. So, those “bone-dry” kind of liberals you mention are still around, publishing in the top journals in the field. And to be fair, they’ve done important work. Starting in the early 1990s, partly in response to liberal democracies becoming more multicultural, they insisted that decent liberal democratic countries must be as inclusive as possible. The state shouldn’t be in the business of favoring or prescribing a particular worldview (whether religious or secular) but instead provide a framework for all its citizens to flourish.

That’s a worthy ideal, don’t get me wrong. But we have to ask: Is it accurate? Does this notion of a “neutral” liberal society, so dear to liberal philosophers, politicians, and pundits, reflect what liberal democratic societies are nowadays?

More here.

How to Raise Your Artificial Intelligence: A Conversation with Alison Gopnik and Melanie Mitchell

Julien Crockett in the LA Review of Books:

A GROWING FEAR and excitement for today’s AI systems stem from the assumption that as they improve, something—someone?—will emerge: feed large language models (LLMs) enough text and, rather than merely extracting statistical patterns in data, they will become intelligent agents with the ability to understand the world.

Alison Gopnik and Melanie Mitchell are skeptical of this assumption. Gopnik, a professor of psychology and philosophy studying children’s learning and development, and Mitchell, a professor of computer science and complexity focusing on conceptual abstraction and analogy-making in AI systems, argue that intelligence is much more complicated than we think. Yes, what today’s LLMs can achieve by consuming huge swaths of text is impressive—and has challenged some of our intuitions about intelligence—but before we can attribute to them something like human intelligence, AI systems will need the ability to actively interact with and engage in the world, creating their own “mental” models about how it works.

How might AI systems reach this next level? And what is needed to ensure their safe deployment? In our conversation, Gopnik and Mitchell consider various approaches, including a framework to describe our role in this next phase of AI development: caregiving

More here.

Market Ideologies

Jamie Martin interviews Oscar Sanchez-Sibony in Phenomenal World:

JAMIE MARTIN: Your new book is quite a bracing and revisionist history of the international political economy of the Cold War from the Soviet point of view. Both here and in your 2014 book, Red Globalization, you offer a distinct view of the Soviet Union as deeply engaged in the world economy. This tells us something key about how the Soviets navigated the global capitalist system, both from within and from without. Your aim seems to be to get us to think anew and more broadly about the nature of the world economy and global capitalism itself.

OSCAR SANCHEZ-SIBONY: Definitely. One continuity between the two books is that I highlight the extent of Soviet integration and the ideologies that encouraged this integration. I try to reconsider the categories that we usually use to understand the Soviet Union, which are largely ideological. When we look at the way the Soviet Union acts in the world, it doesn’t align with the image of the Soviet Union we tend to have—as the advocate for state control over markets.

But you are right, the main aim of the new book is to focus specifically on the transformation of the world at the end of Bretton Woods, not so much to ask questions specific to the Soviet Union, but rather: What is the power that is transforming the world? Bringing the Soviet perspective into our understanding of this period is where I hope the book can make a new intervention. I argue that during this period, the Soviet Union—like many other countries on the periphery—was trying to break down the boundaries that kept it from accessing capital. Under Bretton Woods, this capital was tightly controlled by the United States, which was specifically prohibiting access to the Soviet Union.

In response, the Soviet Union began to trade with European countries that were also trying to break down certain kinds of US monopolies. Through the construction of energy infrastructure, i.e. a series of pipelines, the Soviet Union gained access to capital and promoted the breakdown of all sorts of compartmentalizations that Bretton Woods had imposed. Through pipeline construction, the USSR set up a sort of debt treadmill.

More here.

My New York Intellectuals

Tomiwa Owolade in The Ideas Letter:

I am not from New York. I am not Jewish. I am not a member of a Marxist group. I did not live through the 1930s and 1940s. I am a 27-year-old British-Nigerian who grew up in London. Yet the New York Intellectuals are my people.

They are my people because even though they had ample reason to be defined by their identity, they tried to transcend their personal circumstances with their wide-ranging embrace of culture. They didn’t see themselves, and they should not be seen, simply as Jewish New Yorkers who were advocating anti-fascism and anti-Stalinism in the middle of the 20th century; they possessed a universalist spirit. And this is a spirit to which I aspire.

I remember the wonder I felt reading my first James Baldwin essays from his 1955 collection Notes of a Native Son at my university library or watching I Am Not Your Negro, Raoul Peck’s excellent documentary about Baldwin, on a bright spring afternoon of 2017. I remember in my early 20s picking up Elizabeth Hardwick’s fat collection of criticism (published by NYRB Classics) in a second-hand bookshop and devouring it. I remember discovering the lives and works of other New York Intellectuals in Louis Menand’s monumental 2021 cultural history The Free World: Art and Thought in the Cold War.

More here. Relatedly, Leonard Benardo in The New Statesman:

For many years my mother taught a course on women in literature in a public high school in the Bronx, New York. In the first half of the semester, she selected texts by men writing about women. The second half, books penned by women about women. Hers was a pedagogical conceit that fostered lively discussion among engaged teenagers as to how men and women write differently about the female experience.

Write Like a Man: Jewish Masculinity and the New York Intellectuals is historian Ronnie Grinberg’s variation on my mother’s theme. Grinberg wants to know how the writing of a legendary band of essayists and critics, dubbed the New York Intellectuals by one of its members, reflects what she calls a “secular Jewish masculinity”. Grinberg is especially focused on how the few women writers of the circle were engulfed by a masculine milieu, a trope that recurs in her book like a Wagnerian leitmotif. Did “secular Jewish masculinity” toughen the prose of (and establish a pose for) the New York Intellectuals? What exactly does it mean to “write like a man”, and is it a useful frame to reassess the criticism of this hallowed group?

The New York Intellectuals are customarily associated with that cohort of striving first-generation Jews who met in New York’s great public university, City College of New York (CCNY), and forged comradeships through the impassioned contestation of ideas. From the 1930s through the 1980s, by means of small journals with outsized influence – Partisan Review, Commentary, Encounter – this loosely fitted imagined community produced some of the most incisive and bold American writing of the 20th century. Arguing the World, Joseph Dorman’s documentary from 1997, which traced the intellectual life trajectories of four of its members, Daniel Bell, Irving Kristol, Irving Howe and Nathan Glazer, is the consummate statement of their original convictions and different roads taken. Predominantly male, white and Jewish, there were still others in the polymathic cauldron of the New York Intellectuals who were not: Hannah Arendt, James Baldwin, Mary McCarthy, Elizabeth Hardwick and Dwight Macdonald. What held such a complicated group together and over generations? In a word, ideas. Ideas were the currency, and politics and culture the canvas, upon which the American world of letters took a great leap forward.

Questlove Talks Drums, Dilla, and D’Angelo

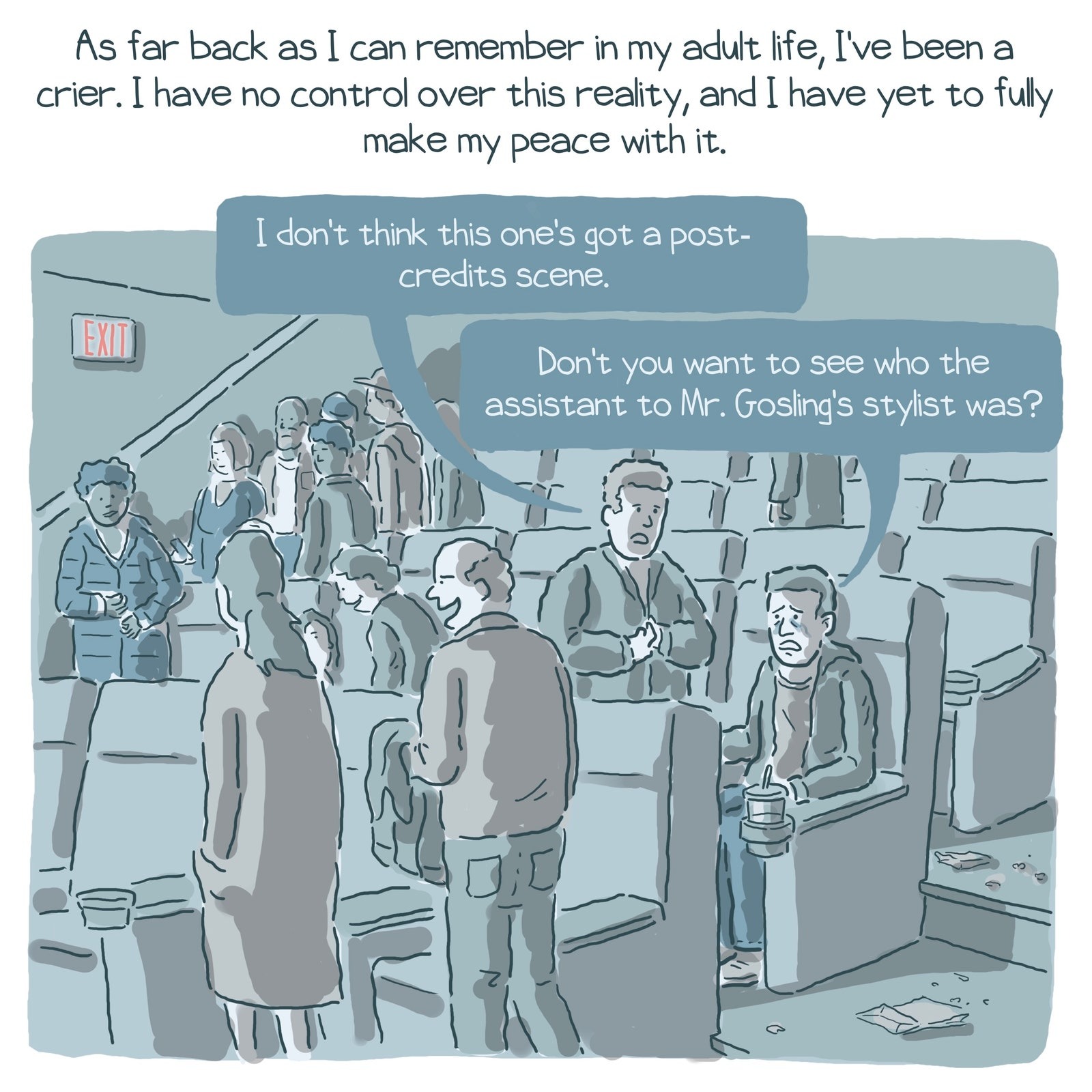

When Dads Cry: A Memoir in Man Tears

David Ostow in The New Yorker:

More here.

On the Crisis of Men

John Baskin in The Point:

I grew up in the age of the crisis of men. Already a frequent subject of national headlines when I became a teenager in the early Nineties (extensively catalogued by Susan Faludi in her 1999 book Stiffed), by the early 2000s, when I was in college, the burdens of contemporary manhood had become the dominant theme of prestige television and film. There were the belated men, the ones who had come “too late,” as Tony Soprano memorably put it to his psychiatrist, and thus instead of getting to build the country with their biceps were stuck in therapy and a rapidly feminizing suburbia, watching helplessly as the old codes were violated and then forgotten completely. There were the nostalgic men, like Don Draper, who aspired to live in the sepia-toned world that he famously pitched as an advertising template to Kodak executives on Mad Men. There were the men who found in violence and criminality a temporary respite from the confines of contemporary manhood—Tony again, but also Walter White on Breaking Bad and Frank Lucas in American Gangster. And there were the ones who impersonated a clearly disintegrated authority to unconsciously comedic effect, like Michael Scott in The Office. If you had to choose, the best among bad options at the time was to become one of Judd Apatow’s hapless husbands; sure, these were pudgy man-children destined to be remembered as footnotes even by their own families, but at least they seemed to be in on the joke.

I grew up in the age of the crisis of men. Already a frequent subject of national headlines when I became a teenager in the early Nineties (extensively catalogued by Susan Faludi in her 1999 book Stiffed), by the early 2000s, when I was in college, the burdens of contemporary manhood had become the dominant theme of prestige television and film. There were the belated men, the ones who had come “too late,” as Tony Soprano memorably put it to his psychiatrist, and thus instead of getting to build the country with their biceps were stuck in therapy and a rapidly feminizing suburbia, watching helplessly as the old codes were violated and then forgotten completely. There were the nostalgic men, like Don Draper, who aspired to live in the sepia-toned world that he famously pitched as an advertising template to Kodak executives on Mad Men. There were the men who found in violence and criminality a temporary respite from the confines of contemporary manhood—Tony again, but also Walter White on Breaking Bad and Frank Lucas in American Gangster. And there were the ones who impersonated a clearly disintegrated authority to unconsciously comedic effect, like Michael Scott in The Office. If you had to choose, the best among bad options at the time was to become one of Judd Apatow’s hapless husbands; sure, these were pudgy man-children destined to be remembered as footnotes even by their own families, but at least they seemed to be in on the joke.

More here.

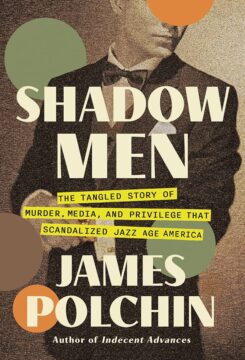

The Tangled Story of Murder, Media, and Privilege That Scandalized Jazz Age America

Marisa Meltzer at the NYT:

The case was the stuff of tabloid dreams. It had everything: murder, blackmail, money, class, secrets, even the occult. And the public, in the time of Prohibition, anti-vice crusades and so-called purity campaigns to combat germs, couldn’t get enough of it.

The case was the stuff of tabloid dreams. It had everything: murder, blackmail, money, class, secrets, even the occult. And the public, in the time of Prohibition, anti-vice crusades and so-called purity campaigns to combat germs, couldn’t get enough of it.

Polchin knows the era, and brings to his account a wealth of colorful supporting detail. While in the Westchester County jailhouse, for instance, Ward (who, despite a lack of experience, was the head of New Rochelle Police Commissioners) was placed in the same relatively luxurious “jail apartment” that another scion, Harry K. Thaw, had inhabited some 15 years earlier, after shooting the architect Stanford White at Madison Square Garden.

We also hear about the dapper William Fallon, a well-known criminal attorney, who in college “devised a three-mirror system that allowed him to cut his own hair, a trick that gave him complete control over the way he looked from almost every conceivable angle.”

more here.

Saturday Poem

Postcard from Home

In sepia a tractor

resting in sagebrush and snow,

rusting, resigned to wind.

A foreshortened farmhouse,

windows bereft of glass.

Last, a mountain range.

Among a hundred others

in a Billings second-hand store

a day before my flight.

A place, passing, someone paused

to take a photograph

of what remained of someone else.

Those exquisite peaks, horizons

never reached, abandoned without apology.

All the ways the West has

of giving up, of getting on.

As if a tourist, I pictured myself

working some other field,

seasons going somewhere else.

I took it with me when I left.

by Mike Barrett

from Post Road Magazine

Friday, June 14, 2024

Music Just Changed Forever

James O’Malley at Persuasion:

Imagine if after Oppenheimer successfully detonated the first atomic bomb, the rest of the world had just shrugged its shoulders and carried on as normal.

Imagine if after Oppenheimer successfully detonated the first atomic bomb, the rest of the world had just shrugged its shoulders and carried on as normal.

Because that’s what seems to have just happened in the entire field of human culture known as “music.”

A few weeks ago, a company called Suno released a new version of its AI-generated music app to the public. It works much like ChatGPT: You type in a prompt describing the song you’d like… and it creates it.

The results are, in my view, absolutely astounding. So much so that I think it will be viewed by history as the end of one musical era and the start of the next one. Just as The Bomb reshaped all of warfare, we’ve reached the point where AI is going to reshape all of music.

More here.

A common misunderstanding about wave-particle duality

Philip Ball in Chemistry World:

‘Particles caught morphing into waves’ was how a recent preprint from researchers in France was widely reported. The timing could not have been better, for this year is the centenary of Louis de Broglie’s remarkable and bold thesis – presented at the Sorbonne in Paris, where some of the team responsible for the new work are based – proposing that matter can behave like waves. De Broglie’s idea was dismissed at first by many of his contemporaries, but was verified three years later when Clinton Davisson and Lester Germer at Bell Laboratories in New York, US, observed diffraction of electrons – an unambiguously wave-like phenomenon – from crystalline nickel. Such waviness became enthroned as a central concept in the newly emergent quantum mechanics under the now famous rubric of ‘wave-particle duality’.

Except… None of this is so simple. The meaning and the significance of wave-particle duality is widely misunderstood, as some of the reporting of the latest work shows. The common perception is that quantum particles really are shape-changers: sometimes little balls of matter, other times smeared-out waves. But physicists have generally been dismissive of that idea.

More here.

The challenges to advanced nuclear reactors aren’t just technical and regulatory

Matthew L. Wald at The Breakthrough Institute:

For good and valid reasons, most of the United States has moved away from having electricity generated, transmitted and delivered by monopolies. The reasons for the change did not primarily have to do with nuclear energy. But a nuclear renaissance could turn out to be a casualty. The old model made construction of a new power plant a shared risk; the new one, in most of the country, turns building a generator into a speculative investment.

For good and valid reasons, most of the United States has moved away from having electricity generated, transmitted and delivered by monopolies. The reasons for the change did not primarily have to do with nuclear energy. But a nuclear renaissance could turn out to be a casualty. The old model made construction of a new power plant a shared risk; the new one, in most of the country, turns building a generator into a speculative investment.

Nearly all of the power reactors now operating in the United States got started by monopolies. Utility executives made their best estimates of future demand, and planned to add generation and transmission to meet it. Regulators in each state, usually called public service commissions, reviewed and approved the plans. The utilities, with a mostly-guaranteed revenue stream, easily sold stocks or bonds or borrowed money to build new generation.

More here.