From NMAAHC:

On “Freedom’s Eve,” or the eve of January 1, 1863, the first Watch Night services took place. On that night, enslaved and free African Americans gathered in churches and private homes all across the country awaiting news that the Emancipation Proclamation had taken effect. At the stroke of midnight, prayers were answered as all enslaved people in Confederate States were declared legally free. Union soldiers, many of whom were black, marched onto plantations and across cities in the south reading small copies of the Emancipation Proclamation spreading the news of freedom in Confederate States. Only through the Thirteenth Amendment did emancipation end slavery throughout the United States.

On “Freedom’s Eve,” or the eve of January 1, 1863, the first Watch Night services took place. On that night, enslaved and free African Americans gathered in churches and private homes all across the country awaiting news that the Emancipation Proclamation had taken effect. At the stroke of midnight, prayers were answered as all enslaved people in Confederate States were declared legally free. Union soldiers, many of whom were black, marched onto plantations and across cities in the south reading small copies of the Emancipation Proclamation spreading the news of freedom in Confederate States. Only through the Thirteenth Amendment did emancipation end slavery throughout the United States.

But not everyone in Confederate territory would immediately be free. Even though the Emancipation Proclamation was made effective in 1863, it could not be implemented in places still under Confederate control. As a result, in the westernmost Confederate state of Texas, enslaved people would not be free until much later. Freedom finally came on June 19, 1865, when some 2,000 Union troops arrived in Galveston Bay, Texas. The army announced that the more than 250,000 enslaved black people in the state, were free by executive decree. This day came to be known as “Juneteenth,” by the newly freed people in Texas.

More here.

Dear Reader,

Dear Reader, A hint of blue on the horizon meant morning was coming. And as they have for the past fifty-four years, Audrey and Gary Revell stepped out their screen door, walked down a ramp, and climbed into their pickup truck. Passing a cup of coffee back and forth, they headed south into Tate’s Hell—one corner of a vast wilderness in Florida’s panhandle where the Apalachicola National Forest runs into the Gulf of Mexico. Soon, they turned off the road and onto a two-track that stretched into a silhouette of pine trees. Their brake lights disappeared into the forest, and after about thirty minutes, they parked the truck along the road just as daylight spilled through the trees. Gary took one last sip of coffee, grabbed a wooden stake and a heavy steel file, and walked off into the woods. Audrey slipped on a disposable glove, grabbed a bucket, and followed. Gary drove the wooden stake, known as a “stob,” into the ground and began grinding it with the steel file. A guttural noise followed as the ground hummed. Pine needles shook, and the soil shivered. Soon, the ground glowed with pink earthworms. Audrey collected them one by one to sell as live bait to fishermen. What drew the worms to the surface seemed like sorcery. For decades, nobody could say exactly why they came up, even the Revells who’d become synonymous with the tradition here. They call it worm grunting.

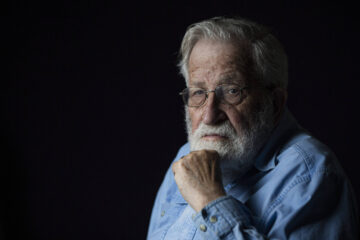

A hint of blue on the horizon meant morning was coming. And as they have for the past fifty-four years, Audrey and Gary Revell stepped out their screen door, walked down a ramp, and climbed into their pickup truck. Passing a cup of coffee back and forth, they headed south into Tate’s Hell—one corner of a vast wilderness in Florida’s panhandle where the Apalachicola National Forest runs into the Gulf of Mexico. Soon, they turned off the road and onto a two-track that stretched into a silhouette of pine trees. Their brake lights disappeared into the forest, and after about thirty minutes, they parked the truck along the road just as daylight spilled through the trees. Gary took one last sip of coffee, grabbed a wooden stake and a heavy steel file, and walked off into the woods. Audrey slipped on a disposable glove, grabbed a bucket, and followed. Gary drove the wooden stake, known as a “stob,” into the ground and began grinding it with the steel file. A guttural noise followed as the ground hummed. Pine needles shook, and the soil shivered. Soon, the ground glowed with pink earthworms. Audrey collected them one by one to sell as live bait to fishermen. What drew the worms to the surface seemed like sorcery. For decades, nobody could say exactly why they came up, even the Revells who’d become synonymous with the tradition here. They call it worm grunting. Besides being a linguist, Chomsky is a respected international political analyst. Of his more than one hundred books, four are specifically about Israel – its wars, governments, and aggressions against the Palestinian people. Despite hundreds of requests from the world press, he has not analyzed the Hamas attack on October 7 and the destruction of Gaza because he had a massive stroke last June. He has difficulty speaking, and the right side of his body is numb.

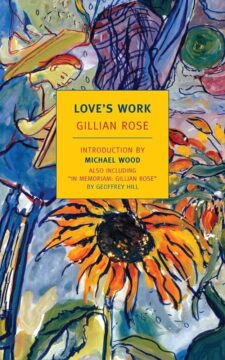

Besides being a linguist, Chomsky is a respected international political analyst. Of his more than one hundred books, four are specifically about Israel – its wars, governments, and aggressions against the Palestinian people. Despite hundreds of requests from the world press, he has not analyzed the Hamas attack on October 7 and the destruction of Gaza because he had a massive stroke last June. He has difficulty speaking, and the right side of his body is numb. “I may die before my time.” The English philosopher Gillian Rose (1947-1995) opened one of her final lectures with these words; soon after, she would die of cancer at the age of 48. Rose’s words were doubly prescient. While her reputation has long been overshadowed by that of her more famous sister, the literary critic Jacqueline Rose, Gillian’s time seems to have arrived at last. Earlier this year in the U.K. Penguin Classics reissued Rose’s forthright memoir Love’s Work (1995), for which she is best known. The book, with its intimate yet unsentimental portrayal of sex, illness and death—in response to her cancer diagnosis, the author reaches “for my favourite whisky bottle” and vows “not to cease wooing, for that is my life affair”—has captivated many of its readers. London’s literati gathered in April at the London Review Bookshop for an event on Love’s Work, and preparations are already underway to mark the thirty years that have passed since the book’s publication and Rose’s death.

“I may die before my time.” The English philosopher Gillian Rose (1947-1995) opened one of her final lectures with these words; soon after, she would die of cancer at the age of 48. Rose’s words were doubly prescient. While her reputation has long been overshadowed by that of her more famous sister, the literary critic Jacqueline Rose, Gillian’s time seems to have arrived at last. Earlier this year in the U.K. Penguin Classics reissued Rose’s forthright memoir Love’s Work (1995), for which she is best known. The book, with its intimate yet unsentimental portrayal of sex, illness and death—in response to her cancer diagnosis, the author reaches “for my favourite whisky bottle” and vows “not to cease wooing, for that is my life affair”—has captivated many of its readers. London’s literati gathered in April at the London Review Bookshop for an event on Love’s Work, and preparations are already underway to mark the thirty years that have passed since the book’s publication and Rose’s death. ‘The trick is to create a world,’

‘The trick is to create a world,’  The average human head contains around 100,000 hairs. Each is connected to a follicle, which can hold one to five hairs. “It’s basically its own organ,” Dr. Mostaghimi said of a scalp follicle. “It has its own stem cells. It regenerates.”

The average human head contains around 100,000 hairs. Each is connected to a follicle, which can hold one to five hairs. “It’s basically its own organ,” Dr. Mostaghimi said of a scalp follicle. “It has its own stem cells. It regenerates.” Cheese fungus, head lice, human sperm, a bee eye, a microplastic bobble: scientific photographer Steve Gschmeissner has imaged them all under the probing lens of a scanning electron microscope (SEM). In his colourized electron micrographs, faecal bacteria resemble thin spaghetti, silica-walled diatoms look like cubes of breakfast cereal and a segmented tardigrade resembles a curled-up, tubby piglet. Gschmeissner, who has been imaging microbes, cancer cells and invertebrates for about 50 years, has crafted an extraordinary array of more than 10,000 SEM images, some of which have been featured in Nature. He spoke to Nature about the importance of scientific images, looking at imploding cancer cells and the miniature world he found on a rotten raspberry.

Cheese fungus, head lice, human sperm, a bee eye, a microplastic bobble: scientific photographer Steve Gschmeissner has imaged them all under the probing lens of a scanning electron microscope (SEM). In his colourized electron micrographs, faecal bacteria resemble thin spaghetti, silica-walled diatoms look like cubes of breakfast cereal and a segmented tardigrade resembles a curled-up, tubby piglet. Gschmeissner, who has been imaging microbes, cancer cells and invertebrates for about 50 years, has crafted an extraordinary array of more than 10,000 SEM images, some of which have been featured in Nature. He spoke to Nature about the importance of scientific images, looking at imploding cancer cells and the miniature world he found on a rotten raspberry. If you are single and looking for a romantic partner, chances are that you have used a

If you are single and looking for a romantic partner, chances are that you have used a  Today is a big one for Kemmerer—for the coal plant workers who will be able to see their future job site being constructed across the highway, for the local construction workers who will be part of a 1,600-person skilled labor force building the plant, and for the local businesses that will take care of the new workforce.

Today is a big one for Kemmerer—for the coal plant workers who will be able to see their future job site being constructed across the highway, for the local construction workers who will be part of a 1,600-person skilled labor force building the plant, and for the local businesses that will take care of the new workforce. “I feel enormous shame about what happened,” Susannah Herbert tells me.

“I feel enormous shame about what happened,” Susannah Herbert tells me. I successfully raised two children to adulthood who, until recently, I called my daughters. But in the past year, one of them has asked that I not refer to her with terms associated with females. She doesn’t feel that words like “her,” “ma’am,” or “daughter” describe her. In fact, she doesn’t think of herself as a woman and does not like to be referred to as “she.” Her pronouns are “they” and “them.”

I successfully raised two children to adulthood who, until recently, I called my daughters. But in the past year, one of them has asked that I not refer to her with terms associated with females. She doesn’t feel that words like “her,” “ma’am,” or “daughter” describe her. In fact, she doesn’t think of herself as a woman and does not like to be referred to as “she.” Her pronouns are “they” and “them.”