Category: Recommended Reading

Tuesday, June 25, 2024

Chatbots and the Problems of Life

Alan Jacobs at The Hedgehog Review:

With increasing availability and sophistication of chatbots, we teachers are seeing a drastic decline in the cost of what in Great Britain is called “commissioning”—that is, getting someone else to do your academic work for you. There are many forms of academic cheating, at various levels of schooling, but commissioning by university students is the one I want to discuss today.

With increasing availability and sophistication of chatbots, we teachers are seeing a drastic decline in the cost of what in Great Britain is called “commissioning”—that is, getting someone else to do your academic work for you. There are many forms of academic cheating, at various levels of schooling, but commissioning by university students is the one I want to discuss today.

Long, long ago, in a pre-Internet galaxy far away, commissioning was costly and therefore rare. It was a bespoke commodity: Typically you’d find someone smart and pay him or her to write an essay for you, or even (this could be done only in large lecture classes whose students were anonymous to their professors) take an exam for you. The talent was almost always local; in a large university, cynical or broke graduate students could supplement their meager stipends quite significantly by catering to the anxieties of academically marginal undergrads.

More here.

Computation Is All Around Us, and You Can See It if You Try

Lance Fortnow in Quanta:

Once you start thinking about computation, you start to see it everywhere. Take mailing a letter through the postal service. Put the letter in an envelope with an address and a stamp on it, and stick it in a mailbox, and somehow it will end up in the recipient’s mailbox. That is a computational process — a series of operations that move the letter from one place to another until it reaches its final destination. This routing process is not unlike what happens with electronic mail or any other piece of data sent through the internet. Seeing the world in this way may seem odd, but as Friedrich Nietzsche is reputed to have said, “Those who were seen dancing were thought to be insane by those who could not hear the music.”

Once you start thinking about computation, you start to see it everywhere. Take mailing a letter through the postal service. Put the letter in an envelope with an address and a stamp on it, and stick it in a mailbox, and somehow it will end up in the recipient’s mailbox. That is a computational process — a series of operations that move the letter from one place to another until it reaches its final destination. This routing process is not unlike what happens with electronic mail or any other piece of data sent through the internet. Seeing the world in this way may seem odd, but as Friedrich Nietzsche is reputed to have said, “Those who were seen dancing were thought to be insane by those who could not hear the music.”

This innate sense of a machine at work can lend a computational perspective to almost any phenomenon, even one as seemingly inscrutable as the concept of randomness.

More here.

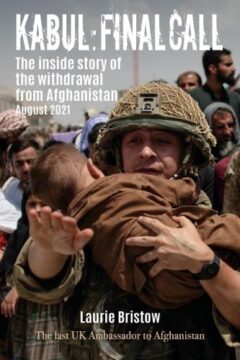

How the west abandoned Afghanistan….and what happened next

Luke Harding in The Guardian:

What went wrong? As Bristow tells it, the west failed because of bad strategy and a loss of will. After the attacks on the twin towers, a military response from the US and its allies was inevitable. Its goal: to exterminate al-Qaeda. As a young reporter, I watched the Taliban’s northern army surrender outside Mazar-i-Sharif. The five-year-old emirate ended in “a wilderness of shimmering desert and telegraph poles”, I wrote in 2001. It was “vanishing into history”.

What went wrong? As Bristow tells it, the west failed because of bad strategy and a loss of will. After the attacks on the twin towers, a military response from the US and its allies was inevitable. Its goal: to exterminate al-Qaeda. As a young reporter, I watched the Taliban’s northern army surrender outside Mazar-i-Sharif. The five-year-old emirate ended in “a wilderness of shimmering desert and telegraph poles”, I wrote in 2001. It was “vanishing into history”.

This prediction turned out to be wrong. After a period in Pakistan’s tribal regions, the Taliban returned. They waged a brutal and increasingly effective insurgency against international and Afghanistan government troops. The conflict cost billions. Meanwhile, George Bush’s administration invaded Iraq. A surge by the next US president, Barack Obama, didn’t bring results. By 2021, the public had lost interest in Afghanistan, seeing it as a for ever war with few benefits.

Washington and London’s mistake, in Bristow’s view, was to seek a military solution to what was a political problem.

More here.

Aravind Srinivas and Lex Fridman: The $1 trillion dollar question for AGI

The Five Stages Of AI Grief

Benjamin Bratton at Noema Magazine:

What is today called “artificial intelligence” should be counted as a Copernican Trauma in the making. It reveals that intelligence, cognition, even mind (definitions of these historical terms are clearly up for debate) are not what they seem to be, not what they feel like, and not unique to the human condition. Obviously, the creative and technological sapience necessary to artificialize intelligence is a human accomplishment, but now, that sapience is remaking itself. Since the paleolithic cognitive revolution, human intelligence has artificialized many things — shelter, heat, food, energy, images, sounds, even life itself — but now, that intelligence itself is artificializable. Kübler-Ross’s stages of grief provide a useful typology of the Western theory of AI: AI Denial, AI Anger, AI Bargaining, AI Depression and AI Acceptance. These genres of “grief” derive from the real and imagined implications of AI for institutional politics, the division of economic labor and many philosophical and religious traditions.

What is today called “artificial intelligence” should be counted as a Copernican Trauma in the making. It reveals that intelligence, cognition, even mind (definitions of these historical terms are clearly up for debate) are not what they seem to be, not what they feel like, and not unique to the human condition. Obviously, the creative and technological sapience necessary to artificialize intelligence is a human accomplishment, but now, that sapience is remaking itself. Since the paleolithic cognitive revolution, human intelligence has artificialized many things — shelter, heat, food, energy, images, sounds, even life itself — but now, that intelligence itself is artificializable. Kübler-Ross’s stages of grief provide a useful typology of the Western theory of AI: AI Denial, AI Anger, AI Bargaining, AI Depression and AI Acceptance. These genres of “grief” derive from the real and imagined implications of AI for institutional politics, the division of economic labor and many philosophical and religious traditions.

more here.

‘You look great! Ozempic?’ The new minefields of weight-loss etiquette

Branigin and Chery in The Washington Post:

Is Delaying Menopause the Key to Longevity?

Gupta and Smith in The New York Times:

In March, the first lady, Jill Biden, announced a new White House women’s health initiative that highlighted a seemingly obscure research question: What if you could delay menopause and all the health risks associated with it? The question comes from a field of research that has started to draw attention over the last few years, as scientists who study longevity and women’s health have come to realize that the female reproductive system is far more than just a baby-maker. The ovaries, in particular, appear to be connected to virtually every aspect of a woman’s health.

In March, the first lady, Jill Biden, announced a new White House women’s health initiative that highlighted a seemingly obscure research question: What if you could delay menopause and all the health risks associated with it? The question comes from a field of research that has started to draw attention over the last few years, as scientists who study longevity and women’s health have come to realize that the female reproductive system is far more than just a baby-maker. The ovaries, in particular, appear to be connected to virtually every aspect of a woman’s health.

They also abruptly stop performing their primary role in midlife. Once that happens, a woman enters menopause, which accelerates her aging and the decline of other organ systems, like the heart and the brain. While women, on average, live longer than men, they spend more time living with diseases or disabilities. The ovaries are “the only organ in humans that we just accept will fail one day,” said Renee Wegrzyn, director of the Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health, a government agency tasked with steering Dr. Biden’s mission. “It’s actually kind of wild that we all just accept that.”

This Portishead Track Is Crazy Beautiful And Here’s Why

The Perverse Magic of Long Ago

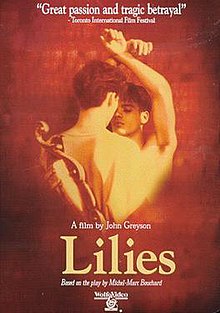

B. Ruby Rich at The Current:

Before he made Lilies (1996), the feature that became his grand masterpiece, John Greyson was already known for his groundbreaking work in video. Identified by his irreverent humor, dance-hall pastiches, fierce political commitment, and brash inventiveness, the Canadian artist had amassed a global following through various showcases, including in New York and at the Berlin Film Festival. I met him when he was just starting out as a young man in New York City championing video and, as he would go on to do throughout his career, the work of other artists.

Before he made Lilies (1996), the feature that became his grand masterpiece, John Greyson was already known for his groundbreaking work in video. Identified by his irreverent humor, dance-hall pastiches, fierce political commitment, and brash inventiveness, the Canadian artist had amassed a global following through various showcases, including in New York and at the Berlin Film Festival. I met him when he was just starting out as a young man in New York City championing video and, as he would go on to do throughout his career, the work of other artists.

Based on a play by Quebec playwright Michel Marc Bouchard, Lilies was Greyson’s first adaptation and his first work to be made in 35 mm. The film wraps its transgressive themes—forbidden sexuality, race, gender, the Catholic Church, murder, and the miscarriage of justice—in a voluptuous style that alternates polished tableaux of an imagined 1912 with rougher scenes staged forty years later.

more here.

Tuesday Poem

O Taste and See

The world is

not with us enough.

O taste and see

the subway Bible poster said,

meaning the Lord, meaning

if anything all that lives

to the imagination’s tongue,

grief, mercy, language,

tangerine, weather, to

breathe them, bite,

savor, chew, swallow, transform

into our flesh our

deaths, crossing the street, plum, quince,

living in the orchard and being

hungry, and plucking

the fruit.

Denise Levertov

from Literature and the Writing Process

Prentice Hall, 1996

Monday, June 24, 2024

3 Quarks Daily Welcomes Our New Monday Columnists

Hello Readers and Writers,

We received a large number of submissions of sample essays in our search for new columnists. Most of them were excellent and it was very hard deciding whom to accept and whom not to. If you did not get selected, it does not at all mean that we didn’t like what you sent; we just have a limited number of slots and also sometimes we have too many people who want to write about the same subject. Today we welcome to 3QD the following persons, in alphabetical order by last name:

- Azadeh Amirsadri

- Katalin Balog

- Gary Borjesson

- Monte Davis

- Mark DeLong

- Eric Feigenbaum

- John Hartley

- Xavier Muller

- Malcolm Murray

- Laurence Peterson

- Eleni Petrakou

- Rachel Robison-Greene

- Eric Schenck

- Daniel Shotkin

- Adele Stanislaus

- Steve Szilagyi

- Jeroen van Baar

- Sander Van de Cruys

I will be in touch with all of you in the next days to schedule a start date. The “Monday Magazine” page will be updated with short bios and photographs of the new writers on the day they start.

Thanks to all of the people who sent samples of writing to us. It was a pleasure to read them all. Congratulations to the new writers!

Best wishes,

Abbas

Sunday, June 23, 2024

Plants Warn, Defend, Scream, Remember, and Plan Ahead

Jeannette Cooperman in The Common Reader:

![]() Tempted as I am to lavish consciousness on everything around me, I was fascinated to learn that tobacco and tomato plants click when they are stressed. The frequency is too high for us to hear these distress calls, but mice and moths do. As a plant dehydrates, the clicking speeds up, as though they are nervously cracking their knuckles. The beach evening primrose reacts to the sound of bees buzzing by secreting a sweeter nectar. Deprived of water, plants avoid dehydration by tightening the pores in their leaves. Roots avoid salt in the soil by inching toward areas that are less salty. Grains of starch shift with gravity, telling a plant which way is up. Flowers plan ahead, turning toward the sun before it rises and timing their pollen production to be ready when a pollinator shows up. Plants release volatile chemicals when they are eaten or infected or mowed down (that summertime freshly-mown-grass smell we all rhapsodize about). Neighboring plants receive this communication and take, when possible, defensive measures.

Tempted as I am to lavish consciousness on everything around me, I was fascinated to learn that tobacco and tomato plants click when they are stressed. The frequency is too high for us to hear these distress calls, but mice and moths do. As a plant dehydrates, the clicking speeds up, as though they are nervously cracking their knuckles. The beach evening primrose reacts to the sound of bees buzzing by secreting a sweeter nectar. Deprived of water, plants avoid dehydration by tightening the pores in their leaves. Roots avoid salt in the soil by inching toward areas that are less salty. Grains of starch shift with gravity, telling a plant which way is up. Flowers plan ahead, turning toward the sun before it rises and timing their pollen production to be ready when a pollinator shows up. Plants release volatile chemicals when they are eaten or infected or mowed down (that summertime freshly-mown-grass smell we all rhapsodize about). Neighboring plants receive this communication and take, when possible, defensive measures.

Most astounding, plants learn.

More here.

Recycling Plastic Is a Dangerous Waste of Time

Frank Celia at Quillette:

By now, you probably know that plastic recycling is a scam. If not, this white paper lays out the case in devastating detail. To summarise, amid calls to reduce plastic garbage in the 1970s and ’80s, the petrochemical industry put forth recycling as a red herring to create the appearance of a solution while it continued to make as much plastic as it pleased. Multiple paper trails indicate that industry leaders knew from the start that recycling could never work at scale. And indeed, it hasn’t. Only about nine percent of plastic worldwide gets recycled, and the US manages only about six percent.

By now, you probably know that plastic recycling is a scam. If not, this white paper lays out the case in devastating detail. To summarise, amid calls to reduce plastic garbage in the 1970s and ’80s, the petrochemical industry put forth recycling as a red herring to create the appearance of a solution while it continued to make as much plastic as it pleased. Multiple paper trails indicate that industry leaders knew from the start that recycling could never work at scale. And indeed, it hasn’t. Only about nine percent of plastic worldwide gets recycled, and the US manages only about six percent.

As bad as this is, the situation might actually be much worse. According to an emerging field of study, the facilities that recycle plastic have been spewing massive amounts of toxins called microplastics into local waterways, soil, and air for decades. In other words, the very industry created to solve the plastic-waste problem has only succeeded in making it worse, possibly exponentially so. While the study that kicked off this new field received some press coverage when it appeared last year, the far-ranging import of its findings has yet to be fully integrated into environmental science. If the research is even close to accurate, and to date it has not been substantively challenged, the implications for waste management policies across the globe will be game-changing.

More here.

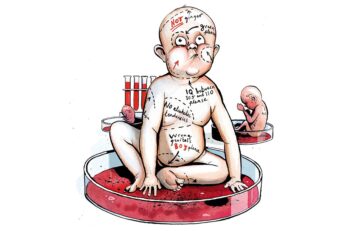

The quiet return of eugenics

Louise Perry in The Spectator:

Emerging technology is about to present parents with a set of ethical questions that make the usual kinds of debates – breast milk or formula? Nanny or daycare? – seem trivial. We have always had the power (more or less) to control our children’s nurture. Before long – perhaps in just a few years – any parent who can afford to will have control over the minutest details of a child’s nature too.

Emerging technology is about to present parents with a set of ethical questions that make the usual kinds of debates – breast milk or formula? Nanny or daycare? – seem trivial. We have always had the power (more or less) to control our children’s nurture. Before long – perhaps in just a few years – any parent who can afford to will have control over the minutest details of a child’s nature too.

The crucial change set to turn our lives upside-down is called ‘preimplantation genetic testing for polygenic disorders’ (PGT-P), hereafter ‘polygenic screening’. Testing a foetus or embryo for some conditions is now a routine part of the modern pregnancy experience. Prenatal Down’s Syndrome tests, for instance, are so widespread that in some Scandinavian countries almost 100 per cent of women choose to abort a foetus diagnosed with the condition, or – if using IVF – not implant the affected embryo. The result is a visible change to these populations: there are simply no more people with Down’s to be seen on the streets of Iceland and Denmark.

More here.

Columbia Law Review article critical of Israel sparks battle between student editors and their board − highlighting fragility of academic freedom

Neal H. Hutchens at The Conversation:

Editors of Columbia Law Review, a prominent journal run by students from the prestigious university’s law school, say the publication’s board of directors urged them on June 2, 2024, to refrain from publishing an article critical of Israel.

Editors of Columbia Law Review, a prominent journal run by students from the prestigious university’s law school, say the publication’s board of directors urged them on June 2, 2024, to refrain from publishing an article critical of Israel.

After the students published the article online the following day, the board, which includes Columbia Law School faculty members and alumni, had the law review’s website taken down.

The board soon relented and allowed the website back online on June 6, including the article in question. But it issued a statement accusing the student editors of failing to properly review the article prior to publication.

The student editors have rejected the assertions in the board’s statement and say they’re “on strike” – refraining from some of their review duties – to protest the board’s attempts to stifle them.

More here.

Donald Sutherland (1935 – 2024) Actor

Willie Mays (1931 – 2024) Baseball Player

James Chance (1953 – 2024) Punk, Jazz, No Wave Musician

Sunday Poem

In Reply

Tell me, Rock, do you think

my mother misses feeling gravity’s sly tug

as she lifted her hand

to brush my cheek?

And would that be enough to lure her back

to sniff her roses,

to feel again the planet’s brow beneath her feet?

It seemed she loved it here.

But what do I know

of the dead, what they miss? I ask you questions,

Rock. And feel in reply,

the absence that grows

when the last of the afternoon birds goes quiet

and the evening birds

haven’t yet sung.

by Clare Rossini

from Plume Magazine

A

A