Category: Recommended Reading

Spycraft Through The Ages

Peter Davidson at Literary Review:

In the 17th century, the Uffizi offered its visitors a rather more diverse range of exhibits than it does now, among them weapons made by some distant precursor of Q Branch. The Scottish traveller James Fraser on a visit to Florence in the 1650s recorded what he saw: ‘A rarity, five pistol barrels joined together to be put in your hat, which is discharged at once as you salute your enemy & bid him farewell … another pistol with eighteen barrels in it to be shot desperately and scatter through a room as you enter.’

In the 17th century, the Uffizi offered its visitors a rather more diverse range of exhibits than it does now, among them weapons made by some distant precursor of Q Branch. The Scottish traveller James Fraser on a visit to Florence in the 1650s recorded what he saw: ‘A rarity, five pistol barrels joined together to be put in your hat, which is discharged at once as you salute your enemy & bid him farewell … another pistol with eighteen barrels in it to be shot desperately and scatter through a room as you enter.’

It is not possible to go very far in the divided Europe of the early modern period without coming across some instance of the many kinds of covert activity that are chronicled in this genial and immensely readable work. The spirit of the age is captured in an extraordinary line in the poem ‘Character of an Ambassador’ by the Dutch polymath and diplomat Constantijn Huygens, which says that ambassadors are ‘honourable spies’. An unexpected page in Nadine Akkerman and Pete Langman’s book is devoted to invisible inks in the family papers of a Lancashire Catholic squire.

more here.

Thursday, June 20, 2024

3QD Is Looking For New Columnists: DEADLINE APPROACHING!

Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,

Here’s your chance to say what you want to the large number of highly educated readers that make up 3QD’s international audience. Several of our regular columnists have had to cut back or even completely quit their columns for 3QD because of other personal and professional commitments and so we are looking for a few new voices. We do not pay, but it is a good chance to draw attention to subjects you are interested in, and to get feedback from us and from our readers.

We would certainly love for our pool of writers to reflect the diversity of our readers in every way, including gender, age, ethnicity, race, sexual orientation, etc., and we encourage people of all kinds to apply. And we like unusual voices and varied viewpoints. So please send us something. What have you got to lose? Click on “Read more” below…

NEW POSTS BELOW

Artificial Women: Sex Dolls, Robot Caregivers, and More Facsimile Females

Marion Thain at the Los Angeles Review of Books:

It seems no coincidence that Yorgos Lanthimos’s cinematic rendition of Alasdair Gray’s 1992 novel Poor Things, released at the end of 2023, would come at a time of obsessive commentary about the possibilities and threats of AI. While Lanthimos’s movie has nothing, ostensibly, to say about digital technologies (beyond its own production process), the publication this year of Julie Wosk’s Artificial Women: Sex Dolls, Robot Caregivers, and More Facsimile Females provides a context for considering the potential of the film in the public imaginary.

It seems no coincidence that Yorgos Lanthimos’s cinematic rendition of Alasdair Gray’s 1992 novel Poor Things, released at the end of 2023, would come at a time of obsessive commentary about the possibilities and threats of AI. While Lanthimos’s movie has nothing, ostensibly, to say about digital technologies (beyond its own production process), the publication this year of Julie Wosk’s Artificial Women: Sex Dolls, Robot Caregivers, and More Facsimile Females provides a context for considering the potential of the film in the public imaginary.

Wosk’s study explores the construction of artificial women in the age of AI as sex robots, care providers, domestic servants, and the disembodied voices of our digital tools and personal assistants. Considering both actually manufactured women and the many artworks that fabricate them as fictions, Artificial Women explores the strange phenomenon of womanhood in the artificially generated human world.

More here.

Eat, Poop, Die: How Animals Make Our World

Leon Vlieger at The Inquisitive Biologist:

What a killer title. Rarely have I seen three snappy words so effectively capture the essence of a concept in biology. What concept is that? Zoogeochemistry. Many scientists have convincingly made the case that it is the small things that run the world. Though it is undeniably true that e.g. microbes and insects have shaped our planet, and continue to do so, it would be a mistake to think that larger animals are just along for the ride. I was stoked the moment the announcement for this book dropped and conservation biologist and marine ecologist Joe Roman did not disappoint. Eat, Poop, Die is fun and fascinating, while always keeping one eye firmly on the facts and complexities of ecology. Is it too soon to start earmarking titles for this year’s top 5? I think not.

What a killer title. Rarely have I seen three snappy words so effectively capture the essence of a concept in biology. What concept is that? Zoogeochemistry. Many scientists have convincingly made the case that it is the small things that run the world. Though it is undeniably true that e.g. microbes and insects have shaped our planet, and continue to do so, it would be a mistake to think that larger animals are just along for the ride. I was stoked the moment the announcement for this book dropped and conservation biologist and marine ecologist Joe Roman did not disappoint. Eat, Poop, Die is fun and fascinating, while always keeping one eye firmly on the facts and complexities of ecology. Is it too soon to start earmarking titles for this year’s top 5? I think not.

More here.

The Myth of Low Black Self-Esteem

John McWhorter at Persuasion:

The 70th anniversary, last month, of the Brown v. The Board of Education decision has had me thinking about a certain conundrum regarding black students and education. Part of what has remained as the enduring legacy of Brown is Kenneth and Mamie Clark’s “Doll Test,” which featured in expert testimony for the case, and showed that a majority of black children preferred white over black dolls. The idea resonated thereafter that black children have a confidence problem, with a hovering implication that this confidence problem affects their performance in school. That hypothesis seemed to be borne out in Claude Steele and Joshua Aronson’s “stereotype threat” paper, their seminal 1995 study that showed that black students’ scores on a GRE test of verbal ability went down when asked to indicate their race on the test—suggesting that their knowledge of negative stereotypes impacted their performance. That paper went on to be cited over 5,000 times and to inspire a host of education reforms.

The 70th anniversary, last month, of the Brown v. The Board of Education decision has had me thinking about a certain conundrum regarding black students and education. Part of what has remained as the enduring legacy of Brown is Kenneth and Mamie Clark’s “Doll Test,” which featured in expert testimony for the case, and showed that a majority of black children preferred white over black dolls. The idea resonated thereafter that black children have a confidence problem, with a hovering implication that this confidence problem affects their performance in school. That hypothesis seemed to be borne out in Claude Steele and Joshua Aronson’s “stereotype threat” paper, their seminal 1995 study that showed that black students’ scores on a GRE test of verbal ability went down when asked to indicate their race on the test—suggesting that their knowledge of negative stereotypes impacted their performance. That paper went on to be cited over 5,000 times and to inspire a host of education reforms.

And certainly you might think that racism would leave black Americans as America’s least confident people. However, the reality is more counterintuitive and interesting than that.

More here.

The life and achievements of Nobel Prize winning physicist Ernest Lawrence

Hanif Abdurraqib Writes A Letter Of Love And Loss To Basketball And Ohio

Gene Seymour at Bookforum:

In this testament to both a sport and a state, Abdurraqib leads with his own heart, one that’s been broken over time by loss of family, friends, even a home. His previous works of cultural criticism (A Little Devil in America, Go Ahead in the Rain, They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us) and poetry (A Fortune for Your Disaster, The Crown Ain’t Worth Much) are steeped in elegy and tempered by irony. He goes all out to sustain this difficult balance in his newest and, one could argue, most ambitious solo performance thus far, an awesomely discursive mixtape of memoir, film criticism, tone poem, and sports punditry interspersed with brief tributes to “legendary Ohio aviators” in whose company he includes Lonnie Carmon, the Black Columbus junk collector who built a plane from some of his salvage and flew it on weekends to astonish and inspire his neighbors. Other Buckeye State heroes need little to no introduction to the rest of us: John Glenn and John Brown, Toni Morrison and Virginia Hamilton.

In this testament to both a sport and a state, Abdurraqib leads with his own heart, one that’s been broken over time by loss of family, friends, even a home. His previous works of cultural criticism (A Little Devil in America, Go Ahead in the Rain, They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us) and poetry (A Fortune for Your Disaster, The Crown Ain’t Worth Much) are steeped in elegy and tempered by irony. He goes all out to sustain this difficult balance in his newest and, one could argue, most ambitious solo performance thus far, an awesomely discursive mixtape of memoir, film criticism, tone poem, and sports punditry interspersed with brief tributes to “legendary Ohio aviators” in whose company he includes Lonnie Carmon, the Black Columbus junk collector who built a plane from some of his salvage and flew it on weekends to astonish and inspire his neighbors. Other Buckeye State heroes need little to no introduction to the rest of us: John Glenn and John Brown, Toni Morrison and Virginia Hamilton.

Though Abdurraqib doesn’t say so explicitly, those last two African American native daughters (Morrison was from Lorain and Hamilton was from Dayton, where, by the way, the Wright Brothers and Paul Lawrence Dunbar were well acquainted with one another) each wrote books declaring that Black people could, indeed, fly.

more here.

The Gods of Logic: Before and after artificial intelligence

Benjamin Labatut in Harper’s Magazine:

We will never know how many died during the Butlerian Jihad. Was it millions? Billions? Trillions, perhaps? It was a fantastic rage, a great revolt that spread like wildfire, consuming everything in its path, a chaos that engulfed generations in an orgy of destruction lasting almost a hundred years. A war with a death toll so high that it left a permanent scar on humanity’s soul. But we will never know the names of those who fought and died in it, or the immense suffering and destruction it caused, because the Butlerian Jihad, abominable and devastating as it was, never happened.

We will never know how many died during the Butlerian Jihad. Was it millions? Billions? Trillions, perhaps? It was a fantastic rage, a great revolt that spread like wildfire, consuming everything in its path, a chaos that engulfed generations in an orgy of destruction lasting almost a hundred years. A war with a death toll so high that it left a permanent scar on humanity’s soul. But we will never know the names of those who fought and died in it, or the immense suffering and destruction it caused, because the Butlerian Jihad, abominable and devastating as it was, never happened.

The Jihad was an imagined event, conjured up by Frank Herbert as part of the lore that animates his science-fiction saga Dune. It was humanity’s last stand against sentient technology, a crusade to overthrow the god of machine-logic and eradicate the conscious computers and robots that in the future had almost entirely enslaved us. Herbert described it as “a thalamic pause for all humankind,” an era of such violence run amok that it completely transformed the way society developed from then onward. But we know very little of what actually happened during the struggle itself, because in the original Dune series, Herbert gives us only the faintest outlines—hints, murmurs, and whispers, which carry the ghostly weight of prophecy. The Jihad reshaped civilization by outlawing artificial intelligence or any machine that simulated our minds, placing a damper on the worst excesses of technology.

More here.

Confirmed. Most robust evidence yet that plant-based diets protect both human and planetary health

Emma Bryce in Anthropocene Magazine:

People who follow a diet rich in plants cut their mortality risk by almost a third, while simultaneously slashing the climate impact of their food by a similar amount. These results come from the largest study ever to analyze the health and environmental impacts of the widely-publicized EAT-Lancet Planetary Health Diet.

People who follow a diet rich in plants cut their mortality risk by almost a third, while simultaneously slashing the climate impact of their food by a similar amount. These results come from the largest study ever to analyze the health and environmental impacts of the widely-publicized EAT-Lancet Planetary Health Diet.

Launched in 2019, the EAT-Lancet Commission brought together reams of research to determine what would be the best way for us to eat on a global scale, to limit the environmental impacts of farming and food. The Commission came up with a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grain and plant-sourced proteins, and lower in—but crucially not excluding—animal-sourced products like meat and dairy milk. That became known as the Planetary Health Diet. Until now, however, the benefits of this diet have been explored mainly on a small scale. The new study takes it up a notch. “This is by far the longest term, large study in actual people to look at both the human and planetary health benefits of the Planetary Health Diet,” says Walter Willett, the Fredrick John Stare professor of epidemiology and nutrition at the Harvard School of Public Health, and lead author on the research.

More here.

AI And AGI: Hype Vs. Reality

Thursday Poem

Silver Maple, Solstice

And still, forty years later, I lean

my cheek to your trunk, breathe

familiar summer. I imagine the sap

pulse running through, what your roots

tell the lake, what they told the other

two other maples you once knew,

network of under earth shared

in the black of Michigan soil. Storms

stole them, trunks yanked back

from decades. Lightning severed,

both fell with such protest they took

a house right down to its stone

basement heart. They never wanted to go.

I share this with them. I share

this with you. Keep up in gale and ice,

hundreds high. Hold fast in spring’s

torment wind. Abandon any blight.

Attend only to the insects

that adore, the birds that make

respectful nests. I say this all as I round

you, touch a secret I don’t want to admit:

one small rusted nail. You’ve grown

around it, taken the scar as a mossed beauty.

But I remember the story another way:

the tin sign it held after we hammered

it into you: Payne Cottage, est. 1982.

Forgive us for wanting to claim

what was never grown for owning.

Forgive us for attempting to harness majesty,

believing it was anything but yours.

by Julie E. Bloemeke

from Poetry Magazine

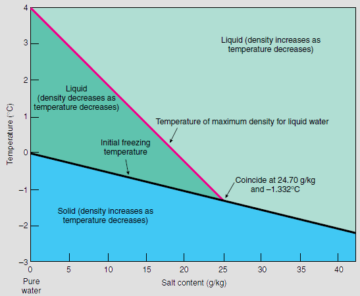

The Enduring Mystery Of How Water Freezes

Elise Cutts at Quanta:

We learn in grade school that water freezes at zero degrees Celsius, but that’s seldom true. In clouds, scientists have found supercooled water droplets as chilly as minus 40 C, and in a lab in 2014, they cooled water to a staggering minus 46 C before it froze. You can supercool water at home: Throw a bottle of distilled water in your freezer, and it’s unlikely to crystallize until you shake it.

We learn in grade school that water freezes at zero degrees Celsius, but that’s seldom true. In clouds, scientists have found supercooled water droplets as chilly as minus 40 C, and in a lab in 2014, they cooled water to a staggering minus 46 C before it froze. You can supercool water at home: Throw a bottle of distilled water in your freezer, and it’s unlikely to crystallize until you shake it.

Freezing usually doesn’t happen right at zero degrees for much the same reason that backyard wood piles don’t spontaneously combust. To get started, fire needs a spark. And ice needs a nucleus — a seed of ice around which more and more water molecules arrange themselves into a crystal structure.

The formation of these seeds is called ice nucleation. Nucleation is so slow for pure water at zero degrees that it might as well not happen at all. But in nature, impurities provide surfaces for nucleation, and these impurities can drastically change how quickly and at what temperature ice forms.

more here.

Wednesday, June 19, 2024

Tillosophy

Anil Gomes in the London Review of Books:

The philosopher Wilfrid Sellars thought that philosophy involved the reconciliation of disparate facts. Consider the disconnect between what he called the ‘scientific’ and the ‘manifest’ images of the world. Science describes a domain of fundamental particles situated in fields of force, spread out across a four-dimensional spacetime. Ordinary human life contains conscious creatures who make decisions, puzzle over problems, and find things good and beautiful. How do we integrate these two stories into a unified whole? One of the tasks of philosophy, Sellars said, was ‘to understand how things in the broadest possible sense of the term hang together in the broadest possible sense of the term’.

The philosopher Wilfrid Sellars thought that philosophy involved the reconciliation of disparate facts. Consider the disconnect between what he called the ‘scientific’ and the ‘manifest’ images of the world. Science describes a domain of fundamental particles situated in fields of force, spread out across a four-dimensional spacetime. Ordinary human life contains conscious creatures who make decisions, puzzle over problems, and find things good and beautiful. How do we integrate these two stories into a unified whole? One of the tasks of philosophy, Sellars said, was ‘to understand how things in the broadest possible sense of the term hang together in the broadest possible sense of the term’.

Daniel Dennett, who died in April, spent much of his career examining matters that populate ordinary thinking about the mind: beliefs, pain, consciousness, free will, the self. He sought to reconcile these aspects of the mind with the scientific story, to show how they can be integrated with such things as neural pathways carrying information, molecules moving according to mechanistic laws, the fundamental particles of atomic physics.

More here.

Cleaning up Cow Burps to Combat Global Warming

Bob Holmes in The Wire:

In the urgent quest for a more sustainable global food system, livestock are a mixed blessing. On the one hand, by converting fibrous plants that people can’t eat into protein-rich meat and milk, grazing animals like cows and sheep are an important source of human food. And for many of the world’s poorest, raising a cow or two — or a few sheep or goats — can be a key source of wealth.

In the urgent quest for a more sustainable global food system, livestock are a mixed blessing. On the one hand, by converting fibrous plants that people can’t eat into protein-rich meat and milk, grazing animals like cows and sheep are an important source of human food. And for many of the world’s poorest, raising a cow or two — or a few sheep or goats — can be a key source of wealth.

But those benefits come with an immense environmental cost. A study in 2013 showed that globally, livestock account for about 14.5% of greenhouse gas emissions, more than all the world’s cars and trucks combined. And about 40% of livestock’s global warming potential comes in the form of methane, a potent greenhouse gas formed as they digest their fibrous diet.

That dilemma is driving an intense research effort to reduce methane emissions from grazers.

More here.

Have beliefs in conspiracy theories increased over time?

Paper at the NIH website:

The public is convinced that beliefs in conspiracy theories are increasing, and many scholars, journalists, and policymakers agree. Given the associations between conspiracy theories and many non-normative tendencies, lawmakers have called for policies to address these increases. However, little evidence has been provided to demonstrate that beliefs in conspiracy theories have, in fact, increased over time. We address this evidentiary gap. Study 1 investigates change in the proportion of Americans believing 46 conspiracy theories; our observations in some instances span half a century. Study 2 examines change in the proportion of individuals across six European countries believing six conspiracy theories. Study 3 traces beliefs about which groups are conspiring against “us,” while Study 4 tracks generalized conspiracy thinking in the U.S. from 2012 to 2021. In no instance do we observe systematic evidence for an increase in conspiracism, however operationalized. We discuss the theoretical and policy implications of our findings.

More here.

David Albert & Tim Maudlin on Von Neumann on the Measurement Problem

Liam Gillick On The Artist’s Novel

David Maroto at Artforum:

THE TWO THINGS THAT I STARTED WITH at Bozar were the novel and the film, which is almost like a cliché. The relationship between a novel and a film always has a particular connection and disconnection at the same time. As a kid, I would look at novelizations of films. Or find the book that became the film. And I was always fascinated by the gap in between these two things: the fact that the novel (if the novel was written before the film) bore no relationship to the film that I saw. And vice versa: that it could work the other way around, that a novel written after a film can often be almost a transliteration of the film. So for this particular exhibition at Bozar, which has to do with the weight of history, I did fall back a little bit on the story structure, on the idea of someone who cannot enter, who cannot arrive, who’s always on the outside. And the novel and the film had the same name in this case—A Max De Vos—but their content was completely different.

THE TWO THINGS THAT I STARTED WITH at Bozar were the novel and the film, which is almost like a cliché. The relationship between a novel and a film always has a particular connection and disconnection at the same time. As a kid, I would look at novelizations of films. Or find the book that became the film. And I was always fascinated by the gap in between these two things: the fact that the novel (if the novel was written before the film) bore no relationship to the film that I saw. And vice versa: that it could work the other way around, that a novel written after a film can often be almost a transliteration of the film. So for this particular exhibition at Bozar, which has to do with the weight of history, I did fall back a little bit on the story structure, on the idea of someone who cannot enter, who cannot arrive, who’s always on the outside. And the novel and the film had the same name in this case—A Max De Vos—but their content was completely different.

more here.

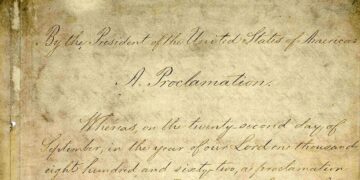

Emancipation Proclamation

From History:

On September 22, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, which declared that as of January 1, 1863, all enslaved people in the states currently engaged in rebellion against the Union “shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.” Lincoln didn’t actually free all of the approximately 4 million men, women and children held in slavery in the United States when he signed the formal Emancipation Proclamation the following January. The document applied only to enslaved people in the Confederacy, and not to those in the border states that remained loyal to the Union. But although it was presented chiefly as a military measure, the proclamation marked a crucial shift in Lincoln’s views on slavery. Emancipation would redefine the Civil War, turning it from a struggle to preserve the Union to one focused on ending slavery, and set a decisive course for how the nation would be reshaped after that historic conflict.

On September 22, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, which declared that as of January 1, 1863, all enslaved people in the states currently engaged in rebellion against the Union “shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.” Lincoln didn’t actually free all of the approximately 4 million men, women and children held in slavery in the United States when he signed the formal Emancipation Proclamation the following January. The document applied only to enslaved people in the Confederacy, and not to those in the border states that remained loyal to the Union. But although it was presented chiefly as a military measure, the proclamation marked a crucial shift in Lincoln’s views on slavery. Emancipation would redefine the Civil War, turning it from a struggle to preserve the Union to one focused on ending slavery, and set a decisive course for how the nation would be reshaped after that historic conflict.

…Lincoln personally hated slavery, and considered it immoral. “If the negro is a man, why then my ancient faith teaches me that ‘all men are created equal;’ and that there can be no moral right in connection with one man’s making a slave of another,” he said in a now-famous speech in Peoria, Illinois, in 1854. But Lincoln didn’t believe the Constitution gave the federal government the power to abolish it in the states where it already existed, only to prevent its establishment to new western territories that would eventually become states.

More here.