Laura Hackett in The Sunday Times:

When Sylvia Townsend Warner expressed an interest in a cottage in East Chaldon, Dorset, in 1930, the surveyor described it as “a small undesirable property, situated in an out of the way place and with no attractions whatever”. Today, one imagines, the cottage, which had no electricity or running water, would be described as “bursting with potential”. Undeterred, Townsend Warner bought it for £90. In escaping London she was following the example of her novel Lolly Willowes, in which an unmarried woman moves to the countryside and becomes a witch. Virginia Woolf once asked her how she knew so much about witches. “Because I am one,” Townsend Warner replied.

When Sylvia Townsend Warner expressed an interest in a cottage in East Chaldon, Dorset, in 1930, the surveyor described it as “a small undesirable property, situated in an out of the way place and with no attractions whatever”. Today, one imagines, the cottage, which had no electricity or running water, would be described as “bursting with potential”. Undeterred, Townsend Warner bought it for £90. In escaping London she was following the example of her novel Lolly Willowes, in which an unmarried woman moves to the countryside and becomes a witch. Virginia Woolf once asked her how she knew so much about witches. “Because I am one,” Townsend Warner replied.

Woolf moved to the countryside herself, to Asheham House, near Lewes in East Sussex, in 1915. And so did Rosamond Lehmann, the author of the scandalous Dusty Answer, in 1941 — her idyll of choice was the Berkshire village of Aldworth. All three women had gone through upheavals: Woolf was recovering from a suicide attempt, Townsend Warner had ended a long relationship and Lehmann had separated from her husband. Rural England offered rest and retreat.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

LUMS is proud and thrilled to acquire the Lutfullah Khan Sound Archive, the premier repository for the literary, cultural, musical, and intellectual heritage of Pakistan and the wider region. There is no other audio library in the region that comes close to matching the scale, richness, and uniqueness of this incredible collection that is bound to serve as an invaluable resource for interdisciplinary scholarship, student learning, and community outreach across various disciplines, including history, sociology, religion, cultural studies, musicology, film studies, and more.

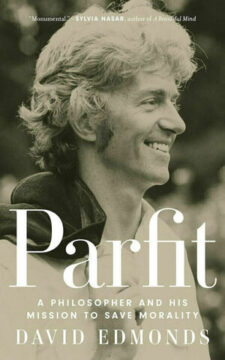

LUMS is proud and thrilled to acquire the Lutfullah Khan Sound Archive, the premier repository for the literary, cultural, musical, and intellectual heritage of Pakistan and the wider region. There is no other audio library in the region that comes close to matching the scale, richness, and uniqueness of this incredible collection that is bound to serve as an invaluable resource for interdisciplinary scholarship, student learning, and community outreach across various disciplines, including history, sociology, religion, cultural studies, musicology, film studies, and more. David Edmonds’ Parfit belongs to a burgeoning genre. There are the two recent collective biographies of Anscombe, Foot, Midgley and Murdoch (by Benjamin Lipscomb and by Claire Mac Cumhaill and Rachael Wiseman). There are M.W. Rowe’s J.L. Austin: Philosopher and D-Day Intelligence Officer and Nikhil Krishnan’s A Terribly Serious Adventure. Earlier works include Ray Monk’s Russell and Wittgenstein volumes, Tom Regan’s Bloomsbury’s Prophet, and Bart Schultz’s books on Sidgwick and the other classical utilitarians. And Edmonds himself is inter alia the author of The Murder of Professor Schlick and the coauthor of Wittgenstein’s Poker.

David Edmonds’ Parfit belongs to a burgeoning genre. There are the two recent collective biographies of Anscombe, Foot, Midgley and Murdoch (by Benjamin Lipscomb and by Claire Mac Cumhaill and Rachael Wiseman). There are M.W. Rowe’s J.L. Austin: Philosopher and D-Day Intelligence Officer and Nikhil Krishnan’s A Terribly Serious Adventure. Earlier works include Ray Monk’s Russell and Wittgenstein volumes, Tom Regan’s Bloomsbury’s Prophet, and Bart Schultz’s books on Sidgwick and the other classical utilitarians. And Edmonds himself is inter alia the author of The Murder of Professor Schlick and the coauthor of Wittgenstein’s Poker.

Yascha Mounk: I’ve been trying to think through the state of economic policy at the moment, and it seems to me that we’re in a strange moment where there was a clear paradigm that economists followed in the ‘90s and perhaps the early 2000s, and that ran aground. Then there was a principled alternative to it that parts of the left tried to put forward, but that seems to have run aground as well.

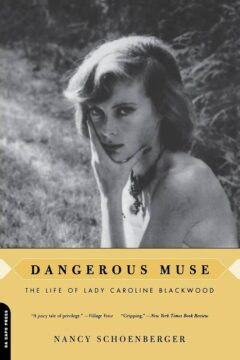

Yascha Mounk: I’ve been trying to think through the state of economic policy at the moment, and it seems to me that we’re in a strange moment where there was a clear paradigm that economists followed in the ‘90s and perhaps the early 2000s, and that ran aground. Then there was a principled alternative to it that parts of the left tried to put forward, but that seems to have run aground as well. In the room devoted to the archives of Lucian Freud in London’s National Portrait Gallery, a strikingly tender painting depicts a young woman with waifish features, blond tresses, and enormous slate-blue eyes. The portrait, “Girl in Bed,” has a delicacy that stands out amid the characteristically mottled, fleshy faces of Freud’s subjects—the slender fingers and crumpled duvet, the high blush on the cheeks. The girl in question is Caroline Blackwood, a twenty-one-year-old heiress of aristocratic extraction, who would soon become the artist’s wife. Freud made ten-odd paintings of Blackwood, charting the zigzag of their relationship, from the sensitive, alluring “Girl Reading” and “Girl in Bed” (both produced in 1952, at the height of their courtship), to the abject “Hotel Bedroom,” from 1954, in which Blackwood appears wizened and withdrawn, while Freud himself stands by the window, lost in shadow.

In the room devoted to the archives of Lucian Freud in London’s National Portrait Gallery, a strikingly tender painting depicts a young woman with waifish features, blond tresses, and enormous slate-blue eyes. The portrait, “Girl in Bed,” has a delicacy that stands out amid the characteristically mottled, fleshy faces of Freud’s subjects—the slender fingers and crumpled duvet, the high blush on the cheeks. The girl in question is Caroline Blackwood, a twenty-one-year-old heiress of aristocratic extraction, who would soon become the artist’s wife. Freud made ten-odd paintings of Blackwood, charting the zigzag of their relationship, from the sensitive, alluring “Girl Reading” and “Girl in Bed” (both produced in 1952, at the height of their courtship), to the abject “Hotel Bedroom,” from 1954, in which Blackwood appears wizened and withdrawn, while Freud himself stands by the window, lost in shadow. I

I In seventeenth-century England, people often commented after a meal: “We ourselves have had ourselves upon our trenchers”. This is an early version of today’s well-worn aphorism, ‘

In seventeenth-century England, people often commented after a meal: “We ourselves have had ourselves upon our trenchers”. This is an early version of today’s well-worn aphorism, ‘ Man-Devil is an entertaining exploration of Mandeville’s ideas, which he set out in The Fable of the Bees and other works. Callanan does not pretend that it is a full-scale biography of Mandeville. Indeed his life story, as far as we know it, could be told in a couple of pages. From a relatively prosperous Rotterdam family, educated in medicine at Leiden University, Mandeville was forced into exile in 1693 as a result of the family’s involvement in the Costerman riots, a protest against the activities of tax farmers, private citizens who collected revenue for the government in return for a large cut. He spent the rest of his life in London, working as a kind of psychiatrist with a particular interest in hypochondria. He died there in 1733.

Man-Devil is an entertaining exploration of Mandeville’s ideas, which he set out in The Fable of the Bees and other works. Callanan does not pretend that it is a full-scale biography of Mandeville. Indeed his life story, as far as we know it, could be told in a couple of pages. From a relatively prosperous Rotterdam family, educated in medicine at Leiden University, Mandeville was forced into exile in 1693 as a result of the family’s involvement in the Costerman riots, a protest against the activities of tax farmers, private citizens who collected revenue for the government in return for a large cut. He spent the rest of his life in London, working as a kind of psychiatrist with a particular interest in hypochondria. He died there in 1733. The very first gay bar I regularly attended in San Francisco was this little hole-in-the-wall called Aunt Charlie’s. In 2003 (the literal second I turned 21), I began to attend their Thursday night party (a party that went on for 20 years, mind you). It was all post-disco freestyle, Hi-NRG, urban—the span of music was from about 1978 to 1982. To paint a picture, the songs would be shit like Gwen McCrae’s “Keep the Fire Burning,” Carol Hahn’s “Do Your Best,” Erotic Drum Band’s “Touch Me Where It’s Hot”—you get the idea. One day, the resident DJ pulled out the 1983 single of Madonna’s “Everybody,” with the iconic collage cover done by Lou Beach. At the time I was in an electroclash band—electroclash being an era of 2000s music that imitated the ’80s. I danced to this Madonna song that I had heard all through my childhood. Now I was an adult, drinking in bars, wondering how a song from 30 years ago felt more like “the future” than anything my friends and I were currently doing. This here is the magic of Madonna. All classics defy time. Every time “Everybody” is played, I come alive on the dance floor.

The very first gay bar I regularly attended in San Francisco was this little hole-in-the-wall called Aunt Charlie’s. In 2003 (the literal second I turned 21), I began to attend their Thursday night party (a party that went on for 20 years, mind you). It was all post-disco freestyle, Hi-NRG, urban—the span of music was from about 1978 to 1982. To paint a picture, the songs would be shit like Gwen McCrae’s “Keep the Fire Burning,” Carol Hahn’s “Do Your Best,” Erotic Drum Band’s “Touch Me Where It’s Hot”—you get the idea. One day, the resident DJ pulled out the 1983 single of Madonna’s “Everybody,” with the iconic collage cover done by Lou Beach. At the time I was in an electroclash band—electroclash being an era of 2000s music that imitated the ’80s. I danced to this Madonna song that I had heard all through my childhood. Now I was an adult, drinking in bars, wondering how a song from 30 years ago felt more like “the future” than anything my friends and I were currently doing. This here is the magic of Madonna. All classics defy time. Every time “Everybody” is played, I come alive on the dance floor.

As reported credulously and breathlessly by just about every major media outlet, there are strange lights in the night sky all over the East Coast; particularly, it seems, in areas

As reported credulously and breathlessly by just about every major media outlet, there are strange lights in the night sky all over the East Coast; particularly, it seems, in areas  A novelist’s name is writ in water, and come a drought may be reduced to a wisp of spume. In his day Anthony Burgess was a very big fish in the literary pond, most famous, or infamous, for the 1962 novel A Clockwork Orange, written in a wonderfully clever Russo-English patois of the author’s invention. The book was adapted for the screen by Stanley Kubrick, who later suppressed the film because of its perceived infatuation with or even encouragement to extreme violence.

A novelist’s name is writ in water, and come a drought may be reduced to a wisp of spume. In his day Anthony Burgess was a very big fish in the literary pond, most famous, or infamous, for the 1962 novel A Clockwork Orange, written in a wonderfully clever Russo-English patois of the author’s invention. The book was adapted for the screen by Stanley Kubrick, who later suppressed the film because of its perceived infatuation with or even encouragement to extreme violence. When Javier Milei was sworn-in as Argentinian president a year ago, the smart money was on a spectacular train wreck. Impulsive, thin-skinned, hyper-ideological and irresistibly drawn to every culture war controversy, no matter how dumb, Milei doesn’t immediately strike you as the kind of leader that gets results. Taking over one of the world’s most notorious economic basketcases at a time of absolute fiscal disarray, Milei’s coming doom seemed all too predictable.

When Javier Milei was sworn-in as Argentinian president a year ago, the smart money was on a spectacular train wreck. Impulsive, thin-skinned, hyper-ideological and irresistibly drawn to every culture war controversy, no matter how dumb, Milei doesn’t immediately strike you as the kind of leader that gets results. Taking over one of the world’s most notorious economic basketcases at a time of absolute fiscal disarray, Milei’s coming doom seemed all too predictable.