Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

Stephen Walt: Is the United States in Decline?

Stephen M. Walt in The Ideas Letter:

This introductory essay advances two main claims. First, I argue that although America’s relative power has declined from its post-Cold War peak, this trend is not as profound as pessimists maintain. The United States still retains enormous advantages relative to all other powers; barring a prolonged series of self-inflicted wounds, it will be the most powerful state in the world for many years to come. Unfortunately, the possibility of decline hastened by misguided policy decisions cannot be ruled out.

This introductory essay advances two main claims. First, I argue that although America’s relative power has declined from its post-Cold War peak, this trend is not as profound as pessimists maintain. The United States still retains enormous advantages relative to all other powers; barring a prolonged series of self-inflicted wounds, it will be the most powerful state in the world for many years to come. Unfortunately, the possibility of decline hastened by misguided policy decisions cannot be ruled out.

Second, I suggest that there is little to fear if America’s relative power declines somewhat, provided US leaders accept this development and adjust their policies accordingly. On the contrary, a more even distribution of power might be beneficial for the United States and for many others around the world. The United States does not need a position of unchallenged primacy to be secure or prosperous, and a somewhat more even distribution of power would force Washington to eschew the dangerous combination of counterproductive unilateralism and liberal hubris that has roiled world politics in recent decades. Although a few states may be alarmed if they can no longer count on unconditional US protection, on balance a modest decline in America’s power position might be a good thing.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Thursday Poem

Just a Bit of Wisdom

If I had just a bit of wisdom

I should walk the Great Path and fear

only straying from it.

Though the way is broad

People love shortcuts.

The court is immaculate,

While the fields are overgrown with weeds,

And the granaries are empty.

They wear silk finery,

Carry sharp swords,

Sate themselves on food and drink

Having wealth in excess.

They are called thieving braggarts.

This is definitely not the Way.

Lao Tzu

from Tao Te Ching

Barnes & Noble Classics, 2005

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Psychosocial Dread at the Heart of Japanese Horror

Michael Atkinson at The Current:

More than the films of any other genre, horror movies are the phenotypes of cultural anxiety—often, you can read the turbulence right on the skin, like hives. In Japan, a nation always rich with wild expressions of social stress, this phenomenon yielded two primary surges: the New Wave attack of the 1950s and ’60s, and the J-horror invasion starting in the late ’80s and ’90s. While these phases reflected different societal shifts, when you take the macro view, they come together to look like one big haunting.

More than the films of any other genre, horror movies are the phenotypes of cultural anxiety—often, you can read the turbulence right on the skin, like hives. In Japan, a nation always rich with wild expressions of social stress, this phenomenon yielded two primary surges: the New Wave attack of the 1950s and ’60s, and the J-horror invasion starting in the late ’80s and ’90s. While these phases reflected different societal shifts, when you take the macro view, they come together to look like one big haunting.

The New Wave horror films are primarily set in the broad swath of history stretching from the early feudal centuries to the Edo period. In America, the Old West is just for westerns, but in Japan, the medieval epoch has always been ripe for use in any genre or mode. Both eras were formative and have proven irresistible because they represent the evolution from semicivilized lawlessness to modernity (still, despite its massive mythology, the Old West, from the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 onward, stretched for maybe eighty-five years, while the Japanese had over half a millennium to play with). The history was always a fuming source of folktales, including kaidan (ghost stories), and that’s the boneyard the New Wave dug into; after the distinctly gentle ghostliness of Kenji Mizoguchi’s Ugetsu (1953), the most notable kaidan adaptations include Kaneto Shindo’s Onibaba (1964), Kuroneko (1968), and The Iron Crown (1972), as well as Nobuo Nakagawa’s The Ghost of Kasane (1957), Black Cat Mansion (1958), and The Ghost of Yotsuya (1959); Masaki Kobayashi’s lavish Kwaidan (1964); and Kimiyoshi Yasuda and Yoshiyuki Kuroda’s Yokai Monsters trilogy (1968–69).

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

How A 10-Year-Old Girl Wrote Japan’s Most Insane Horror Film

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

How a Moldy Cantaloupe Took Fleming’s Penicillin from Discovery to Mass Production

Hannah Thomasy in The Scientist:

Tucked away in a dusty corner of St. Mary’s Hospital in London lies a tiny, one-room museum dedicated to one of the most important discoveries in the history of medicine: a mold that changed the world. Curators have recreated Alexander Fleming’s laboratory as it would have looked on the day of his discovery, from the cigarettes that he smoked incessantly while working in the lab to a replica of the famous Petri dish of Penicillium.

Tucked away in a dusty corner of St. Mary’s Hospital in London lies a tiny, one-room museum dedicated to one of the most important discoveries in the history of medicine: a mold that changed the world. Curators have recreated Alexander Fleming’s laboratory as it would have looked on the day of his discovery, from the cigarettes that he smoked incessantly while working in the lab to a replica of the famous Petri dish of Penicillium.

While samples of the original isolate, known as Penicillium rubens IMI 15378, are cryopreserved in collections around the world, this strain is curiously absent from modern-day commercial penicillin production. The isolate used in mass production today didn’t originate in Fleming’s laboratory at all; instead, the multi-billion dollar industry uses a microbe derived from a moldy cantaloupe found at a fruit market in Peoria, Illinois in the early 1940s.1

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Indicators of an aging brain: A 20-year study

From Phys.Org:

Johns Hopkins University-led researchers, working with the Biomarkers for Older Controls at Risk for Dementia (BIOCARD) cohort, have found that certain factors are linked to faster brain shrinkage and quicker progression from normal thinking abilities to mild cognitive impairment (MCI). People with type 2 diabetes and low levels of specific proteins in their cerebrospinal fluid showed more rapid brain changes and developed MCI sooner than others.

Johns Hopkins University-led researchers, working with the Biomarkers for Older Controls at Risk for Dementia (BIOCARD) cohort, have found that certain factors are linked to faster brain shrinkage and quicker progression from normal thinking abilities to mild cognitive impairment (MCI). People with type 2 diabetes and low levels of specific proteins in their cerebrospinal fluid showed more rapid brain changes and developed MCI sooner than others.

Long-term studies tracking brain changes over many years are rare but valuable. Previous research mostly provided snapshots in time, which can’t show how individual brains change over the years. By following participants for up to 27 years (20-year median), this study offers new insights into how health conditions might speed up brain aging.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

On Minor Characters And Human Possibility

Yiyun Li at Harper’s Magazine:

At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, I led a virtual discussion of War and Peace, with the thought that someone else might enjoy reading the novel with me. Three thousand people ended up following along, which seemed to me a good way to connect people in isolation. But there were disagreements. Someone complained to a friend of mine that she didn’t see why I bothered to read Tolstoy, who was a “patriarchal figure.” An acquaintance told me that I did not need to read Tolstoy to feel like a writer. Feel, I marveled: What did she mean? It was baffling that people would feel strongly about what I did with my reading time; it was as though someone took personal offense that I often eat broccoli.

Later, at a writers’ festival, I gave a talk on what I’d learned from reading War and Peace. Afterward, someone who had been in the audience asked me if I knew anything about Tolstoy’s life. I did, as I had read his biography and visited Yasnaya Polyana, his estate outside Moscow. “He was an aristocrat!” the woman said. “He had servants. His wife served him. He was a horrible man!”

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Wednesday, November 13, 2024

Dame Tracey Emin On Her Art And Life

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

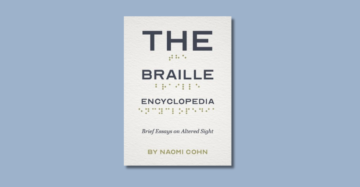

The Radical Gaze of ‘The Braille Encyclopedia’

Patricia Parks at The Millions:

In Vermeer’s Woman in Blue Reading a Letter, the observer is drawn into a simple domestic scene: the titular woman stands illuminated in the light of, we presume, an unseen window. The expression on her face as she reads is perhaps one of surprise, certainly one of concentration. In this vivid, static painting, she seems even more still and more rooted, unmoving though clearly moved by what she is reading. And the observer is similarly absorbed by this intimate moment.

In Vermeer’s Woman in Blue Reading a Letter, the observer is drawn into a simple domestic scene: the titular woman stands illuminated in the light of, we presume, an unseen window. The expression on her face as she reads is perhaps one of surprise, certainly one of concentration. In this vivid, static painting, she seems even more still and more rooted, unmoving though clearly moved by what she is reading. And the observer is similarly absorbed by this intimate moment.

This interpretation, such as it is, is arrived at first through the eyes: the light and color, the posture of the woman and her expression, the singularity of the room. Vermeer’s painting is a touchstone of sorts in Naomi Cohn’s compelling memoir, The Braille Encyclopedia: Brief Essays on Altered Sight. To her, with her very limited ability to see, the story is not in the painting; it is the painting. “Who cares what is on the letter?” she writes. “Look at how Vermeer makes folds with paint. Look at the intensity of his looking, how he chose what to see.”

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Charlotte Shane Discusses Desire, Sex Work, And Writing

Jamie Hood and Charlotte Shane at Bookforum:

JAMIE HOOD: Hello!

JAMIE HOOD: Hello!

CHARLOTTE SHANE: Hi! You look gorgeous—make sure to put that in.

HOOD: Oh, I will. An Honest Woman (Simon & Schuster, $26) is a sort of origin story, about the boys you grew up with and the cultural milieu of your youth, as well as an erotic Bildungsroman that eventually traces your history in sex work. I’m curious where you began.

SHANE: I went back to earlier writing and found a lot that surprised me. You learn how unreliable you are as a narrator, even to yourself. The more I looked, the more I realized one story—of how I was this homely teenager with few romantic options—was wrong. I had several boys who confessed their love to me, and this really good-looking boyfriend, but the facts of your life are not always the most important. I was so invested in this idea of being unattractive, I had to live my life that way, to be like, “Any guy who’s interested in me is weird, there’s something really wrong with him.” That feels so feminine: considering yourself from an ambiguous male vantage point. You’re trying to satisfy an ideal, but because it’s not the ideal of a real person, it’s impossible to meet the requirements. You exist in an aspirational state of failure.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Auden’s Island: The poet in the postwar era

Alan Jacobs at The Hedgehog Review:

When, on January 19, 1939, W.H. Auden boarded at Southampton a ship bound for New York City, he could not have known that he would never live in England again. But some months earlier, he had told his friend Christopher Isherwood that he wanted to settle permanently in the United States. Almost as soon as he arrived in New York, he began to rethink his calling as a poet, and, moreover, to reconsider the social role and function of poetry. (He also began a spiritual pilgrimage that would lead him to embrace the Christian faith of his childhood.)

When, on January 19, 1939, W.H. Auden boarded at Southampton a ship bound for New York City, he could not have known that he would never live in England again. But some months earlier, he had told his friend Christopher Isherwood that he wanted to settle permanently in the United States. Almost as soon as he arrived in New York, he began to rethink his calling as a poet, and, moreover, to reconsider the social role and function of poetry. (He also began a spiritual pilgrimage that would lead him to embrace the Christian faith of his childhood.)

His work of this period combined a proclamation of the value of microcultures with a commitment to an intellectual cosmopolitanism. He celebrated the “local understanding” achieved in the informal salon run by a German émigré, Elizabeth Mayer, from her home on Long Island, but what bound the members of that salon to one another was the combination of cultural and national diversity with moral sympathy. In a poem composed immediately after the Nazis invaded Poland in September 1939, he wrote:

Defenceless under the night

Our world in stupor lies;

Yet, dotted everywhere,

Ironic points of light

Flash out wherever the Just

Exchange their messages….

Like God in one ancient definition, “the Just” are a community whose center is everywhere and circumference nowhere. They are homeless in the world but at home with one another.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Book Review – The Story Of Earth’s Climate In 25 Discoveries: How Scientists Found The Connections Between Climate And Life

Leon Vlieger at The Inquisitive Biologist:

An important goal for Prothero is to explain how we know what we know so that readers understand how the climate works and why it changes. As such, much attention is given to the numerous lines of evidence on which palaeoclimatology draws. The fossils that show Greenland was once carpeted by lush forests while Antarctica was the stomping ground of dinosaurs. The stratigraphical evidence that tells stories of past ice ages by way of dropstones, erratics, and glacial till deposits. The fossil riverbeds in today’s deserts. The cyclical climate patterns revealed by repeating strata with obscure names such as cyclothems and varves. The palaeoclimatological archives contained in deep-sea sediment cores and Arctic ice cores. The numerous lines of evidence for plate tectonics. The geochemical evidence showing past changes in the composition of the atmosphere. The importance of microfossils, etc., etc. Prothero provides plenty of background material for the reader not schooled in geology and palaeontology. The only notable omission here is tree rings that are only mentioned in passing; unfortunate, as the story of dendrochronology is fascinating.

An important goal for Prothero is to explain how we know what we know so that readers understand how the climate works and why it changes. As such, much attention is given to the numerous lines of evidence on which palaeoclimatology draws. The fossils that show Greenland was once carpeted by lush forests while Antarctica was the stomping ground of dinosaurs. The stratigraphical evidence that tells stories of past ice ages by way of dropstones, erratics, and glacial till deposits. The fossil riverbeds in today’s deserts. The cyclical climate patterns revealed by repeating strata with obscure names such as cyclothems and varves. The palaeoclimatological archives contained in deep-sea sediment cores and Arctic ice cores. The numerous lines of evidence for plate tectonics. The geochemical evidence showing past changes in the composition of the atmosphere. The importance of microfossils, etc., etc. Prothero provides plenty of background material for the reader not schooled in geology and palaeontology. The only notable omission here is tree rings that are only mentioned in passing; unfortunate, as the story of dendrochronology is fascinating.

A secondary aim of this book is to show how life and climate have interacted with each other.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Judith Butler: Is Anti-Zionism Antisemitism?

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

If You’re Sure How the Next Four Years Will Play Out, I Promise: You’re Wrong

Adam Grant in the New York Times:

In a landmark study, the psychologist Philip Tetlock evaluated several decades of predictions about political and economic events. He found that “the average expert was roughly as accurate as a dart-throwing chimpanzee.” Although skilled forecasters were much better, they couldn’t see around corners. No one could foresee that a driver’s wrong turn would put Archduke Franz Ferdinand in an assassin’s path, precipitating World War I.

In a landmark study, the psychologist Philip Tetlock evaluated several decades of predictions about political and economic events. He found that “the average expert was roughly as accurate as a dart-throwing chimpanzee.” Although skilled forecasters were much better, they couldn’t see around corners. No one could foresee that a driver’s wrong turn would put Archduke Franz Ferdinand in an assassin’s path, precipitating World War I.

Yet a hunch about the future can feel like a certainty because the present is so overwhelmingly, well, present. It’s staring us in the face. Especially in times of great anxiety, it can be all too tempting — and all too dangerous — to convince ourselves the future is just as visible.

In 1919, when the Treaty of Versailles ended World War I, the Allied powers celebrated. The world was finally returning to peace. They had no idea that the national humiliation of that treaty would sow the seeds of another world war. Just as a tragedy can leave us oblivious to the possibility of silver linings, a triumph can blind us to the prospect of terrible reverberations.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Fallibilism can break America’s political fever

Kwame Anthony Appiah in The Washington Post:

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Can AI review the scientific literature — and figure out what it all means?

Helen Pearson in Nature:

When Sam Rodriques was a neurobiology graduate student, he was struck by a fundamental limitation of science. Even if researchers had already produced all the information needed to understand a human cell or a brain, “I’m not sure we would know it”, he says, “because no human has the ability to understand or read all the literature and get a comprehensive view.”

When Sam Rodriques was a neurobiology graduate student, he was struck by a fundamental limitation of science. Even if researchers had already produced all the information needed to understand a human cell or a brain, “I’m not sure we would know it”, he says, “because no human has the ability to understand or read all the literature and get a comprehensive view.”

Five years later, Rodriques says he is closer to solving that problem using artificial intelligence (AI). In September, he and his team at the US start-up FutureHouse announced that an AI-based system they had built could, within minutes, produce syntheses of scientific knowledge that were more accurate than Wikipedia pages1. The team promptly generated Wikipedia-style entries on around 17,000 human genes, most of which previously lacked a detailed page.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Wednesday Poem

Full of Days

Job died when he was “full of days”,

a wonderful expression. I too would like to arrive

at the point of feeling “full of days,”

and to close with a smile the brief circle

that is our life. I can still take pleasure in it, yes;

still enjoy the moon reflected on the sea,

the kisses of the woman I love, her presence

that gives meaning to everything; still savor

those Sunday afternoons at home in winter,

lying on the sofa filling pages with symbols

and formulae, dreaming of capturing another

small secret from among the thousands that still

surround us . . . I like to look forward to still tasting

from this golden chalice, to life that is teeming,

both tender and hostile, clear and inscrutable,

unexpected . . . But I have already drunk deep

of the bittersweet draft of this chalice, and if an

angel were to come for me right now, saying,

“Carlo, it’s time,” I would not ask to be left

even long enough to finish this sentence.

I would just smile up at him and follow.

by Carlo Rovelli

from The Order of Time

Riverhead Books, 2018

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going bydonating now.

Tuesday, November 12, 2024

A Brief History of the Most Famous Swear Word in the World

Jesse Sheidlower at Literary Hub:

In all of English there are few words rich enough in their history and variety of use to warrant a dedicated dictionary that runs to hundreds of pages and multiple editions. That fuck is at the same time one of the most notorious, popular, and emotive words in the language makes it all the more fascinating—and deserving of the attention given to it in this volume.

In all of English there are few words rich enough in their history and variety of use to warrant a dedicated dictionary that runs to hundreds of pages and multiple editions. That fuck is at the same time one of the most notorious, popular, and emotive words in the language makes it all the more fascinating—and deserving of the attention given to it in this volume.

There’s a good chance you have some story about your relationship to the word fuck. You asked a teacher what it meant; you used it inappropriately in a professional situation; you were thrilled to learn a story about its origin (probably false—see “Where It’s Not From,” below); you were disciplined by a parent or guardian for saying it; you discovered that a romantic partner liked—or really did not like—hearing it, or used it in a way that had a strong effect on you.

How has this word, which has been around for many hundreds of years, maintained both its intense interest and its uncommon power?

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sean Carroll: Emergence and Layers of Reality

Sean Carroll at Preposterous Universe:

![]() Emergence is a centrally important concept in science and philosophy. Indeed, the existence of higher-level emergent properties helps render the world intelligible to us — we can sensibly understand the macroscopic world around us without a complete microscopic picture. But there are various different ways in which emergence might happen, and a tendency for definitions of emergence to rely on vague or subjective criteria. Recently Achyuth Parola and I wrote a paper trying to clear up some of these issues: What Emergence Can Possibly Mean. In this solo podcast I discuss the way we suggest to think about emergence, with examples from physics and elsewhere.

Emergence is a centrally important concept in science and philosophy. Indeed, the existence of higher-level emergent properties helps render the world intelligible to us — we can sensibly understand the macroscopic world around us without a complete microscopic picture. But there are various different ways in which emergence might happen, and a tendency for definitions of emergence to rely on vague or subjective criteria. Recently Achyuth Parola and I wrote a paper trying to clear up some of these issues: What Emergence Can Possibly Mean. In this solo podcast I discuss the way we suggest to think about emergence, with examples from physics and elsewhere.

Transcript here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

I want to make the case for the power of thinking in the third person. The first person, of course, comes quite naturally to us. We have a vivid sense of our experiences and perspectives: This is who and what I am. People will live their lives with “main character energy.” Yet, with a little more work, we can also view ourselves the way historians and social scientists might: as creatures shaped by larger forces and bound by a culture’s pre-written scripts. That means seeing ourselves as the inheritor and inhabitant of various social identities — and, therefore, as a person like every other.

I want to make the case for the power of thinking in the third person. The first person, of course, comes quite naturally to us. We have a vivid sense of our experiences and perspectives: This is who and what I am. People will live their lives with “main character energy.” Yet, with a little more work, we can also view ourselves the way historians and social scientists might: as creatures shaped by larger forces and bound by a culture’s pre-written scripts. That means seeing ourselves as the inheritor and inhabitant of various social identities — and, therefore, as a person like every other.