Guian Mckee in Time Magazine:

In recent years, major new studies have tried to rehabilitate the presidency of Jimmy Carter, who died on Dec. 29 at age 100. They’ve emphasized a range of underappreciated accomplishments in everything from foreign policy to environmental protection and racial equity. These accounts still acknowledge Carter’s failures but balance them with a longer-term perspective on how his presidency changed the United States and the world.

In recent years, major new studies have tried to rehabilitate the presidency of Jimmy Carter, who died on Dec. 29 at age 100. They’ve emphasized a range of underappreciated accomplishments in everything from foreign policy to environmental protection and racial equity. These accounts still acknowledge Carter’s failures but balance them with a longer-term perspective on how his presidency changed the United States and the world.

This positive reappraisal, however, hasn’t extended to health care policy. This makes sense considering how devastating the battle over health care was to Carter during his presidency. Congress rejected his major health care policy initiatives, and his grudging support for a much more limited national health insurance plan in part spurred Sen. Ted Kennedy (D-Mass.) to challenge the incumbent Carter from the left in the 1980 Democratic presidential primary.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Exosomes are tiny bubbles made by cells to carry proteins and genetic material to other cells. While still early, research into these mysterious bubbles suggests they may be involved in aging or be responsible for cancers spreading across the body.

Exosomes are tiny bubbles made by cells to carry proteins and genetic material to other cells. While still early, research into these mysterious bubbles suggests they may be involved in aging or be responsible for cancers spreading across the body. When asked why he didn’t begin writing novels until his 30s, the celebrated Czech author Milan Kundera said he didn’t have the requisite experience when he was younger. “This jerk that I was, I wouldn’t like to see him,” he added. Many of us look back at our former selves and wince to recall our immaturity. We vary quite a lot in the degree to which we feel friendly toward, and connected to, both our former and our future selves. Psychologists call this trait self-continuity, and suggest that it carries enormous weight in determining our long-term well-being.

When asked why he didn’t begin writing novels until his 30s, the celebrated Czech author Milan Kundera said he didn’t have the requisite experience when he was younger. “This jerk that I was, I wouldn’t like to see him,” he added. Many of us look back at our former selves and wince to recall our immaturity. We vary quite a lot in the degree to which we feel friendly toward, and connected to, both our former and our future selves. Psychologists call this trait self-continuity, and suggest that it carries enormous weight in determining our long-term well-being. My New Year’s resolutions have always had one thing in common: They’ve been all about me. Some years I’ve vowed to pick up my high school French again; some years I’ve sworn off impulse shopping; and some years (OK, every year) I’ve promised myself I’d go to bed earlier. The goal, though, has always been the same: to become a better, happier version of myself. But while there’s nothing wrong with self-improvement, experts say that focusing on our relationships with the people around us may go a long way to making us happier.

My New Year’s resolutions have always had one thing in common: They’ve been all about me. Some years I’ve vowed to pick up my high school French again; some years I’ve sworn off impulse shopping; and some years (OK, every year) I’ve promised myself I’d go to bed earlier. The goal, though, has always been the same: to become a better, happier version of myself. But while there’s nothing wrong with self-improvement, experts say that focusing on our relationships with the people around us may go a long way to making us happier. Percival Everett’s first novel was published in 1983. How long ago was that? It was same year Madonna, R.E.M. and Metallica released their first albums. Much of the world has only recently begun to catch up with him.

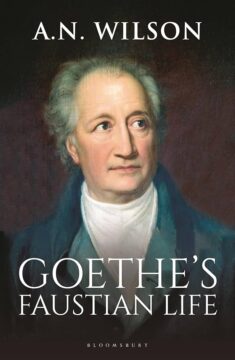

Percival Everett’s first novel was published in 1983. How long ago was that? It was same year Madonna, R.E.M. and Metallica released their first albums. Much of the world has only recently begun to catch up with him. Boyle’s treatment of Goethe’s readings and uses of Kant would make for a tidy monograph in itself. As would Boyle’s analysis of Goethe’s studies and experiments in optics, in the meaning and structure of light. The conclusions drawn were erroneous, but it has been argued that the treatise on colours, the Farbenlehre, is a stylistic, intellectual masterpiece at the heart of Goethe’s achievements. An achievement relating Goethe to Spinoza on the one hand, and to various schools of light-mysticism, of ‘illuminism’ in a literal vein, both Western and Oriental (Persian doctrines and literature fascinated Goethe).

Boyle’s treatment of Goethe’s readings and uses of Kant would make for a tidy monograph in itself. As would Boyle’s analysis of Goethe’s studies and experiments in optics, in the meaning and structure of light. The conclusions drawn were erroneous, but it has been argued that the treatise on colours, the Farbenlehre, is a stylistic, intellectual masterpiece at the heart of Goethe’s achievements. An achievement relating Goethe to Spinoza on the one hand, and to various schools of light-mysticism, of ‘illuminism’ in a literal vein, both Western and Oriental (Persian doctrines and literature fascinated Goethe). Regular people in countries like Bolivia depend on imported food and fuel for their daily lives. To import food and fuel you need dollars — or some other international currency like euros or yen or yuan or whatever. Bolivia can get dollars two ways — by selling exports or by selling bonds. If it doesn’t sell enough exports — for example, if gas prices drop and its exports are worth less — it has to sell bonds in order to keep importing.

Regular people in countries like Bolivia depend on imported food and fuel for their daily lives. To import food and fuel you need dollars — or some other international currency like euros or yen or yuan or whatever. Bolivia can get dollars two ways — by selling exports or by selling bonds. If it doesn’t sell enough exports — for example, if gas prices drop and its exports are worth less — it has to sell bonds in order to keep importing. At what point does an aside become a tangent, a tangent a digression, a digression a meander, a meander a ramble, a ramble a circumlocution, a circumlocution an excursus and an excursus a cul-de-sac? The reader has time to consider such matters while reading A.N. Wilson’s elastic-waisted but hardly unintelligent new biography, “Goethe: His Faustian Life.”

At what point does an aside become a tangent, a tangent a digression, a digression a meander, a meander a ramble, a ramble a circumlocution, a circumlocution an excursus and an excursus a cul-de-sac? The reader has time to consider such matters while reading A.N. Wilson’s elastic-waisted but hardly unintelligent new biography, “Goethe: His Faustian Life.” One Hundred Years of Solitude has a near-mythical status for me that no other book does. Aged about 14, bored one day during the summer holidays, I found the Picador 1978 paperback edition on my parents’ bookshelf. I opened it on a whim, and read one of the most iconic first sentences in existence: “Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.” I immediately sat down on the sofa and read for a further three hours. I date my life as a reader of literature to that afternoon, to that first sentence which I still know by heart. I have since reread it only once, 10 years later, because I wanted to wait until I had forgotten what happens. I’ll read it again as soon as the details have once more faded from my memory, and I can’t wait.

One Hundred Years of Solitude has a near-mythical status for me that no other book does. Aged about 14, bored one day during the summer holidays, I found the Picador 1978 paperback edition on my parents’ bookshelf. I opened it on a whim, and read one of the most iconic first sentences in existence: “Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.” I immediately sat down on the sofa and read for a further three hours. I date my life as a reader of literature to that afternoon, to that first sentence which I still know by heart. I have since reread it only once, 10 years later, because I wanted to wait until I had forgotten what happens. I’ll read it again as soon as the details have once more faded from my memory, and I can’t wait. A

A