Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

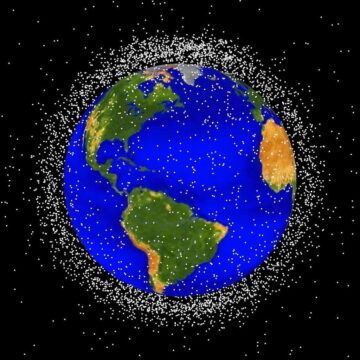

Does Space Need Environmentalists?

Nathaniel Scharping at Noema:

“Everywhere that humans go, they cause ecological problems. The environmental history is clear about this,” Daniel Capper, an adjunct professor of philosophy at the Metropolitan State University of Denver, who is a vocal proponent of such a movement, recently told me. Capper, who has a Walt Whitman beard and speaks with a genial kind of urgency, argues that commonly-held beliefs about the value of land and wilderness on Earth should hold just as much sway in space. He is part of a small but growing chorus of intellectuals who argue that we must carve out protections sooner rather than later — backed by a concrete theoretical and legal framework — for certain areas of the solar system. The United Nations has convened a working group on the use of space resources, and the International Astronomical Union has set up a different working group to delineate places of special scientific value on the moon.

“Everywhere that humans go, they cause ecological problems. The environmental history is clear about this,” Daniel Capper, an adjunct professor of philosophy at the Metropolitan State University of Denver, who is a vocal proponent of such a movement, recently told me. Capper, who has a Walt Whitman beard and speaks with a genial kind of urgency, argues that commonly-held beliefs about the value of land and wilderness on Earth should hold just as much sway in space. He is part of a small but growing chorus of intellectuals who argue that we must carve out protections sooner rather than later — backed by a concrete theoretical and legal framework — for certain areas of the solar system. The United Nations has convened a working group on the use of space resources, and the International Astronomical Union has set up a different working group to delineate places of special scientific value on the moon.

Some researchers have proposed creating a planetary park system in space, while others advocate for a circular space economy that minimizes the need for additional resources.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Rouen’s Municipal Library, 1959–1964

Annie Ernaux at the Paris Review:

If it hadn’t been for a philosophy classmate at the Lycée Jeanne-d’Arc, I never would have entered the municipal library. I wouldn’t have dared. I vaguely assumed it was open only to university students and professors. Not at all, my classmate told me, everyone’s allowed in, you can even settle down and work there. It was winter. When I would return after class to my closet-size room in the Catholic girls’ dorm, I found it gloomy and awfully chilly. Going to a café was out of the question, I didn’t have any money. The thought of working on my philosophy essays, surrounded by books, somewhere that was surely well heated, was an appealing prospect. The first time I entered the municipal library, at once shy and determined, I suppose, I was struck by the silence, by the sight of people reading or writing as they sat at long rows of tables pushed together and overhung by lamps. I was struck by its hushed and studious atmosphere, which had something religious about it. There was that very particular smell—a little like incense—which I would rediscover later, elsewhere, in other venerable libraries. A sanctuary that required treading cautiously, almost on tiptoe: the opposite of the commotion and confusion of the lycée. An impressive and severe world of knowledge. I didn’t know its rituals, which I had to learn: how to consult the card catalogue, separated into “Authors” and “Subjects”; how to record the call numbers accurately; how to deposit the card into a basket, before waiting, occasionally a long time, sometimes shorter, for the requested book. I got into the habit of coming to the library regularly and writing my philosophy essays there.

If it hadn’t been for a philosophy classmate at the Lycée Jeanne-d’Arc, I never would have entered the municipal library. I wouldn’t have dared. I vaguely assumed it was open only to university students and professors. Not at all, my classmate told me, everyone’s allowed in, you can even settle down and work there. It was winter. When I would return after class to my closet-size room in the Catholic girls’ dorm, I found it gloomy and awfully chilly. Going to a café was out of the question, I didn’t have any money. The thought of working on my philosophy essays, surrounded by books, somewhere that was surely well heated, was an appealing prospect. The first time I entered the municipal library, at once shy and determined, I suppose, I was struck by the silence, by the sight of people reading or writing as they sat at long rows of tables pushed together and overhung by lamps. I was struck by its hushed and studious atmosphere, which had something religious about it. There was that very particular smell—a little like incense—which I would rediscover later, elsewhere, in other venerable libraries. A sanctuary that required treading cautiously, almost on tiptoe: the opposite of the commotion and confusion of the lycée. An impressive and severe world of knowledge. I didn’t know its rituals, which I had to learn: how to consult the card catalogue, separated into “Authors” and “Subjects”; how to record the call numbers accurately; how to deposit the card into a basket, before waiting, occasionally a long time, sometimes shorter, for the requested book. I got into the habit of coming to the library regularly and writing my philosophy essays there.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Tuesday Poem

Coffee House Poets

They like to write

where people are.

They like a little noise

with their silence.

They want to look up

and see something.

They want to be surprised.

They like the flow

of bodies around them.

Or perhaps it’s just loneliness–

yes, that too.

But more than that:

they like the atmosphere

a little smoke laden.

They like aromas–

coffee, tobacco, meat frying.

They like the sudden revelation

as eyes look off

or blur with tears

looking across a table.

Where others court eternity,

they’re in love with the moment

in all its tawdriness and glory,

that instant when truth appears

out of nowhere–a truth

as simple and as natural

as people sitting together

in a room over coffee

in all their vulnerability

and their humanness.

by Albert Huffstickler

from Poetic Outlaws

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Monday, December 9, 2024

Getting Lost And Found In The Bob Dylan Archives

Justin Taylor at Bookforum:

The Bob Dylan Archive had long been a subject of rumor and legend. Few outside the singer’s inner circle knew for sure whether it existed, let alone what it contained. It was kind of hard to picture Mr. Dont Look Back himself boxing up old notebooks for posterity. But if he didn’t, someone did. When the sale was announced in March 2016, the New York Times described it as “deeper and more vast than even most Dylan experts could imagine, promising untold insight into the songwriter’s work. . . . A private trove of his work, dating back to his earliest days as an artist, including lyrics, correspondence, recordings, films and photographs.”

The Bob Dylan Archive had long been a subject of rumor and legend. Few outside the singer’s inner circle knew for sure whether it existed, let alone what it contained. It was kind of hard to picture Mr. Dont Look Back himself boxing up old notebooks for posterity. But if he didn’t, someone did. When the sale was announced in March 2016, the New York Times described it as “deeper and more vast than even most Dylan experts could imagine, promising untold insight into the songwriter’s work. . . . A private trove of his work, dating back to his earliest days as an artist, including lyrics, correspondence, recordings, films and photographs.”

Steadman Upham, then the president of the University of Tulsa, promised that “we will be set up for serious scholars and for people who have a record of being Dylanologists.” Upham died in 2017, and GKFF has since bought out the university’s stake in the Archive, but the promise of access has been kept. Two early hires were the curator Michael Chaiken (who has worked on the archives of Norman Mailer, Nicholas Ray, and D. A. Pennebaker), and the poet/biographer/Dylan-freak Robert Polito. Though it would be years before the Center would open its doors, Chaiken and Polito began bringing writers to Tulsa.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Inayat Khan & Universal Sufism

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Contemporary Poets Respond (in Verse) to Taylor Swift

Kristie Frederick Daugherty at Literary Hub:

When Taylor Swift announced the title of her new album The Tortured Poets Department at the Grammy Awards in February, a question popped into my mind: How can poets and poetry enter into conversation with Swift? As a debut-era Swiftie, I knew that her lyrics contain all of the elements of poetry, and that her songwriting is simply unparalleled and literary.

When Taylor Swift announced the title of her new album The Tortured Poets Department at the Grammy Awards in February, a question popped into my mind: How can poets and poetry enter into conversation with Swift? As a debut-era Swiftie, I knew that her lyrics contain all of the elements of poetry, and that her songwriting is simply unparalleled and literary.

As quickly as the question formed in my mind, so did an answer: Ask the best poets writing today to respond with a poem to one specific song of Swift’s without using direct lyrics or titles; then, create a one-of-a-kind ekphrastic poetry anthology which leans into the spirit of Swift’s songwriting, highlighting the way she interacts with her huge fan base whom she has trained to search for “Easter Eggs” in everything from her songwriting to the clothes she wears.

I started with Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Diane Seuss, who not only said yes, but also offered a list of a poets to contact. From that moment the project blossomed into something absolutely beautiful, with 113 poets joyfully agreeing to take part.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Wuhan lab samples hold no close relatives to virus behind COVID

Smriti Mallapaty in Nature:

After years of rumours that the virus that causes COVID-19 escaped from a laboratory in China, the virologist at the centre of the claims has presented data on dozens of new coronaviruses collected from bats in southern China. At a conference in Japan this week, Shi Zhengli, a specialist on bat coronaviruses, reported that none of the viruses stored in her freezers are the most recent ancestors of the virus SARS-CoV-2.

After years of rumours that the virus that causes COVID-19 escaped from a laboratory in China, the virologist at the centre of the claims has presented data on dozens of new coronaviruses collected from bats in southern China. At a conference in Japan this week, Shi Zhengli, a specialist on bat coronaviruses, reported that none of the viruses stored in her freezers are the most recent ancestors of the virus SARS-CoV-2.

Shi was leading coronavirus research at the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV), a high-level biosafety laboratory, when the first cases of COVID-19 were reported in that city. Soon afterwards, theories emerged that the virus had leaked — either by accident or deliberately — from the WIV.

Shi has consistently said that SARS-CoV-2 was never seen or studied in her lab. But some commentators have continued to ask whether one of the many bat coronaviruses her team collected in southern China over decades was closely related to it. Shi promised to sequence the genomes of the coronaviruses and release the data.

The latest analysis, which has not been peer reviewed, includes data from the whole genomes of 56 new betacoronaviruses, the broad group to which SARS-CoV-2 belongs, as well as some partial sequences. All the viruses were collected between 2004 and 2021.

“We didn’t find any new sequences which are more closely related to SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2,” said Shi, in a pre-recorded presentation at the conference, Preparing for the Next Pandemic: Evolution, Pathogenesis and Virology of Coronaviruses, in Awaji, Japan, on 4 December.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Geoff Hinton: Will Digital Intelligence Replace Biological Intelligence?

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Secret Pentagon War Game That Offers a Stark Warning for Our Times

William Langewiesche in the New York Times:

The descent — in the language of nuclear war, an escalation — is shaped by grave uncertainties. How well do my enemies understand me, and how well do I understand them? Furthermore, how does my understanding of their understanding affect their understanding of me? These and similar questions stand like the endless images in opposing mirrors, but without diminishing in size. The threat they pose is immediate and real. It leaves us to grapple with the central truth of the nuclear age: The sole way for humanity to survive is to communicate clearly, to sustain that communication indefinitely and to understand how readily communications can be misunderstood. Crucial to handling the attendant distrust are fallback communications integral to the art of de-escalation — an art that has been neglected and is now dangerously foundering.

The descent — in the language of nuclear war, an escalation — is shaped by grave uncertainties. How well do my enemies understand me, and how well do I understand them? Furthermore, how does my understanding of their understanding affect their understanding of me? These and similar questions stand like the endless images in opposing mirrors, but without diminishing in size. The threat they pose is immediate and real. It leaves us to grapple with the central truth of the nuclear age: The sole way for humanity to survive is to communicate clearly, to sustain that communication indefinitely and to understand how readily communications can be misunderstood. Crucial to handling the attendant distrust are fallback communications integral to the art of de-escalation — an art that has been neglected and is now dangerously foundering.

After the Cold War, the two great powers paid less attention to the matter. Surprise attacks were their main concern, but they assumed that the existing warning systems and retaliatory capabilities were sufficient to ward off such events. At the Pentagon, ambitious officers chose some other track to advance their careers. Terrorism, cyberwarfare, even global warming — that’s where the action lay.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

‘Queer’ Review: The Seductive, Damaged Charm of Daniel Craig

Manhola Dargis in The New York Times:

When William Lee stalks through Mexico City in “Queer,” he often seems on high alert, though sometimes he’s just high. The louche protagonist in Luca Guadagnino’s soft-serve adaptation of the William S. Burroughs autobiographical novella, Lee is a smoker, drinker, heroin addict and epic storyteller. He’s a refugee from America who at times seems like a visitor from another dimension. Played with sensitivity and predatory heat by Daniel Craig, Lee has a feverish mind, eyes like searchlights and a mouth that’s quick to sneer. There are moments when he seems possessed, though it’s not often clear what’s taken hold of his soul.

When William Lee stalks through Mexico City in “Queer,” he often seems on high alert, though sometimes he’s just high. The louche protagonist in Luca Guadagnino’s soft-serve adaptation of the William S. Burroughs autobiographical novella, Lee is a smoker, drinker, heroin addict and epic storyteller. He’s a refugee from America who at times seems like a visitor from another dimension. Played with sensitivity and predatory heat by Daniel Craig, Lee has a feverish mind, eyes like searchlights and a mouth that’s quick to sneer. There are moments when he seems possessed, though it’s not often clear what’s taken hold of his soul.

As in the book, the movie follows Lee during an adventure that takes him from Mexico circa 1950 further south — to Panama, Ecuador and parts distinctly unknown — only to bring him back to where he began or thereabouts. The novella runs a scant 160 or so pages, and while it’s crammed with incisive details, characters and observations, the story is fairly compressed and, for the most part, focuses on Lee’s preoccupation with another American, Eugene Allerton (Drew Starkey), a tall, good-looking veteran. Lee first sees him gawking at a street cockfight, a distinctly Guadagnino take on what romantic stories call the meet cute.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Why Are Our Brains So Big? Because They Excel at Damage Control

Shelly Fan in Singularity Hub:

Compared to other primates, our brains are exceptionally large. Why?

Compared to other primates, our brains are exceptionally large. Why?

A new study comparing neurons from different primates pinpointed several genetic changes unique to humans that buffer our brains’ ability to handle everyday wear and tear. Dubbed “evolved neuroprotection,” the findings paint a picture of how our large brains gained their size, wiring patterns, and computational efficiency. It’s not just about looking into the past. The results could also inspire new ideas to tackle schizophrenia, Parkinson’s disease, and addiction caused by the gradual erosion of one type of brain cell. Understanding these wirings may also spur artificial brains that learn like ours. The results haven’t yet been reviewed by other scientists. But to Andre Sousa at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, who wasn’t involved in the work, the findings can help us understand “human brain evolution and all the potentially negative and positive things that come with it.”

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sunday, December 8, 2024

December 2024 Athlete of the Month: Morgan Meis

Interview from the website of Core City Fitness in Detroit:

Interviewer: How long have you been doing CrossFit?

Morgan Meis: Well, see, the thing is I had a massive heart attack last October. This was considered not good by most of my doctors. I mean, not to brag or anything, but it was a super-huge heart attack. Some say legendary. The jokers in the cardiology community call the type of heart attack I had a widowmaker. Anyway, it is probably in poor taste to go on and on about one’s heart attack, so I’ll just say it was a doozy. Did I mention that about 12 percent of people survive a widowmaker? Legendary. Where was I? Oh yeah, once I got out of cardiac rehab my cardiologist said two things 1) you’re only allowed to eat grass and a few crunchy grains from now on and 2) get your ass to some regular exercise. I came back the next week (which was last February) and told her I’m going to do Crossfit. “Are you frickin’ nuts?” she asked me. “Yes,” I answered.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The AI We Deserve

Evgeny Morozov in Boston Review:

For a technology that seemed to materialize out of thin air, generative AI has had a remarkable two-year rise. It’s hard to believe that it was only on November 30, 2022, when ChatGPT, still the public face of this revolution, became widely available. There has been a lot of hype, and more is surely to come, despite talk of a bubble now on the verge of bursting. The hawkers do have a point. Generative AI is upending many an industry, and many people find it both shockingly powerful and shockingly helpful. In health care, AI systems now help doctors summarize patient records and suggest treatments, though they remain fallible and demand careful oversight. In creative fields, AI is producing everything from personalized marketing content to entire video game environments. Meanwhile, in education, AI-powered tools are simplifying dense academic texts and customizing learning materials to meet individual student needs.

In my own life, the new AI has reshaped the way I approach both everyday and professional tasks, but nowhere is the shift more striking than in language learning. Without knowing a line of code, I recently pieced together an app that taps into three different AI-powered services, creating custom short stories with native-speaker audio. These stories are packed with tricky vocabulary and idioms tailored to the gaps in my learning. When I have trouble with words like Vergesslichkeit (“forgetfulness” in German), they pop up again and again, alongside dozens of others that I’m working to master.

In over two decades of language study, I’ve never used a tool this powerful. It not only boosts my productivity but redefines efficiency itself—the core promises of generative AI. The scale and speed really are impressive. How else could I get sixty personalized stories, accompanied by hours of audio across six languages, delivered in just fifteen minutes—all while casually browsing the web? And the kicker? The whole app, which sits quietly on my laptop, took me less than a single afternoon to build, since ChatGPT coded it for me. Vergesslichkeit, au revoir!

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Simes Agonistes

Keith Gessen in The Ideas Letter:

Earlier this year I wrote a piece for the New Yorker about military analysts and their arguments over the war in Ukraine. Why did so many people think that Russia would take Kyiv in a matter of days? Was it an area studies issue, an overreliance on quantitative methods, a credulity about Russian propaganda? What conclusions, if any, could we draw for the rest of the war from this initial error? And so on.

One of the military analysts I spoke with spent a lot of time on Twitter. He used it to find photos and videos from the battlefield, gauge public opinion in Ukraine, and get answers to questions about his own work. As a result, he was deeply concerned about all the mistakes, misinterpretations, and bad actors on the platform. He was willing to talk about the war in Ukraine. But what he really wanted to talk about was Twitter.

I thought about this analyst when I saw the news, in September, that Dimitri Simes, longtime president of the Center for the National Interest think tank in Washington, D.C., had been indicted by the Biden Justice Department for sanctions violations and money laundering, chiefly for his work as a talk show host on Russia’s most popular TV station, Channel One. There was war, I thought, and then, as my military analyst well knew, there was info-war. Simes was the latest casualty.

Who was Dimitri Simes?

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Class Cleavages

Alex Browne in Phenomenal World:

On January 10, 2021, four days after the January 6 attack at the Capitol, Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan Chase, Citigroup, and Morgan Stanley—four of the six largest banks in the United States—suspended contributions to the Republican Party. The next day, the Chamber of Commerce declared that politicians who had voted against certifying the election would no longer receive its financial support. “The president’s conduct last week was absolutely unacceptable and completely inexcusable,” said Thomas Donahue, the Chamber’s CEO: “By his words and actions, he has undermined our democratic institutions and ideals.” Over 123 Fortune 500 firms—collectively accounting for a quarter of American GDP—eventually did the same.

American capital’s boycott against the Republican Party, signifying new heights of estrangement between organized business and what it saw as a dangerously anti-system conservative movement, lasted less than two months. By March, the Chamber had reversed course. “We do not believe it is appropriate to judge members of Congress solely based on their votes on the electoral certification,” explained Ashlee Rich Stephenson, the Chamber’s senior political strategist. Citi and JPMorgan Chase resumed their donations to the GOP in June, once a bipartisan group of senators emerged to separate infrastructure spending from the administration’s proposals for a tax increase. In the 2022 primaries, Republican members of Congress who refused to certify the 2020 election still faced an average fundraising penalty of $100,000 from Fortune 500 PACs; this penalty dropped in the 2022 general election, and once again in the 2024 primaries. Within two years, organized business’s opposition to the Republican Party had disintegrated.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Comprador Nation

Ammar Ali Jan in Sidecar:

Last week in Islamabad, a series of violent confrontations erupted between supporters of Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI), the party of the jailed former Prime Minister Imran Khan, and state security forces. Hundreds were injured as police and paramilitary rangers used bullets and tear gas to disperse the crowds. PTI’s chair, Gohar Khan, claimed that at least a dozen were killed. The brutal crackdown was facilitated by internet stoppages, roadblocks and mass arrests of PTI staffers and activists. These heavy-handed tactics have succeeded in clearing the streets, but they have also highlighted the growing instability of Pakistan’s hybrid regime, characterized by an amalgam of civilian administrators and military rulers. What are the causes and consequences of this legitimacy crisis? Is it a matter of conjunctural politics, or of long-term structural trends?

Since Pakistan’s first military coup in 1958, US backing for the army – seen as an essential counterweight to Soviet influence – has made the country’s political sphere hostile for democratic forces. By signing up to the infamous SEATO and CENTO agreements, the military brought Pakistan into America’s Cold War camp, making it a crucial subordinate power in South Asia. Since then, it has directly ruled the country on-and-off for more than thirty years.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Mary McGee (1936 – 2024) Motorsport Racing Pioneer

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Rohit Bal (1961 – 2024) Fashion Designer

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Silvia Pinal (1931 – 2024) Actor

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.