Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

Eric Kaufmann on “The Third Awokening”

Yascha Mounk at his own Substack:

Yascha Mounk: I’ve read a lot of your work and have been in conversation with you for a long time. You’re somebody who approaches the growth and influence of what some people call wokeness, what I call the identity synthesis, what you and your recent work have called the Third Awokening, from a social scientific perspective.

Where do these ideas come from? How did they gain so much currency and why are you concerned about them?

Eric Kaufmann: Obviously you in your book, The Identity Trap, give a pretty good account of one route, I think, towards this, which is sort of the whole idea of strategic essentialism that came out of left-wing intellectual thought. I know yourself and Francis Fukuyama and Chris Rufo and others have sketched out its development out of essentially the post-Marxist left. What I try to do in my book, The Third Awokening, is to look at the more liberal humanitarian, if you like, prong of this, which runs through psychotherapy and gets us towards a kind of humanitarian extremism. And so I put a lot of emphasis on this idea of cranking the dial of humanitarianism.

Eric Kaufmann: Obviously you in your book, The Identity Trap, give a pretty good account of one route, I think, towards this, which is sort of the whole idea of strategic essentialism that came out of left-wing intellectual thought. I know yourself and Francis Fukuyama and Chris Rufo and others have sketched out its development out of essentially the post-Marxist left. What I try to do in my book, The Third Awokening, is to look at the more liberal humanitarian, if you like, prong of this, which runs through psychotherapy and gets us towards a kind of humanitarian extremism. And so I put a lot of emphasis on this idea of cranking the dial of humanitarianism.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Satyajit Ray and Claude Sautet – 1981

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Are the Internet and AI affecting our memory? What the science says

Helen Pearson in Nature:

Adrian Ward had been driving confidently around Austin, Texas, for nine years — until last November, when he started getting lost. Ward’s phone had been acting up, and Apple maps had stopped working. Suddenly, Ward couldn’t even find his way to the home of a good friend, making him realize how much he’d relied on the technology in the past. “I just instinctively put on the map and do what it says,” he says.

Adrian Ward had been driving confidently around Austin, Texas, for nine years — until last November, when he started getting lost. Ward’s phone had been acting up, and Apple maps had stopped working. Suddenly, Ward couldn’t even find his way to the home of a good friend, making him realize how much he’d relied on the technology in the past. “I just instinctively put on the map and do what it says,” he says.

Ward’s experience echoes a common complaint: that the Internet is undermining our memory. This fear has shown up in several surveys over the past few years, and even led one software firm to coin the term ‘digital amnesia’ for the experience of forgetting information because you know a digital device has stored it instead. Last year, Oxford University Press announced that its word of the year was ‘brain rot’ — the deterioration of someone’s mental state caused by consuming trivial online content.

“What you’ll see out there is all kinds of dire predictions about digital amnesia, and ‘we’re gonna lose our memory because we don’t use it anymore’,” says Daniel Schacter, who studies memory at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Eldridge Cleaver’s Soul on Ice—Still Relevant 50 years later

By Goth Grammarist:

Cleaver was born into and lived in a segregated world and didn’t question it. Once segregation was made illegal*, he realizes the world he was in, writing “Prior to 1954, we lived in an atmosphere of novocain. Negroes found it necessary, in order to maintain whatever sanity they could, to remain somewhat aloft and detached from ‘the problem.’ We accepted indignities and the mechanics of the apparatus of oppression without reacting by sitting-in or holding mass demonstrations.” (Cleaver, 4-5) Most of the African American writers I have read either grew up before segregation ended or after.

Cleaver was born into and lived in a segregated world and didn’t question it. Once segregation was made illegal*, he realizes the world he was in, writing “Prior to 1954, we lived in an atmosphere of novocain. Negroes found it necessary, in order to maintain whatever sanity they could, to remain somewhat aloft and detached from ‘the problem.’ We accepted indignities and the mechanics of the apparatus of oppression without reacting by sitting-in or holding mass demonstrations.” (Cleaver, 4-5) Most of the African American writers I have read either grew up before segregation ended or after.

He writes that “America has been a schizophrenic nation. It’s two conflicting images of itself were never reconciled, because never before has the survival of its most cherished myths made a reconciliation mandatory.” It was only when segregation was abolished that white America had to learn to share space with black America. And this, as Cleaver notes, allowed black people to become angry. This was when people were able to acknowledge those feelings some had kept ignoring. What is incredibly frustrating about Cleaver’s writing, is that it’s still relevant. He wrote over 1/2 a century ago and he was pissed off (rightly so) and demanded change. I wish he sounded dated. I wish his anger sounded unnecessary. But his words, his rhetoric could be written today.

More here. (Note: In honor of Black History Month, at least one post will be devoted to its 2025 theme of “African Americans and Labor” throughout the month of February)

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

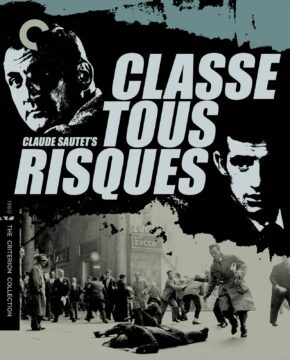

The films of Claude Sautet Defied The New Wave Fraternity

Sean Nam at The Baffler:

When the French crime film Classe tous risques—the English title, The Big Risk, fails to capture the pun on insurance policies and travel accommodations—premiered in Paris in March 1960, it was undercut by no less a modern heretic than Jean-Luc Godard, whose Breathless had premiered only a week before. Both films starred Jean-Paul Belmondo, an ex-boxer whose hardscrabble looks were belied by his soft pout. He plays underworld citizens in both films: In Breathless, the scapegrace Michel Poiccard, stroking his thumb across his lips in a pastiche of Humphrey Bogart, and in Classe tous risques a young louche named Éric Stark. The film’s director, Claude Sautet, was thirty-six at the time, having apprenticed for years as an assistant director of middling, prefab projects—George Franju’s Eyes Without a Face (1960), which Sautet cowrote, being a key exception. Sautet is mostly an unknown quantity in anglophone circles and Classe tous risques is probably his most recognizable achievement thanks to the Criterion Collection, which gave it one of its comprehensive DVD treatments in 2008.

When the French crime film Classe tous risques—the English title, The Big Risk, fails to capture the pun on insurance policies and travel accommodations—premiered in Paris in March 1960, it was undercut by no less a modern heretic than Jean-Luc Godard, whose Breathless had premiered only a week before. Both films starred Jean-Paul Belmondo, an ex-boxer whose hardscrabble looks were belied by his soft pout. He plays underworld citizens in both films: In Breathless, the scapegrace Michel Poiccard, stroking his thumb across his lips in a pastiche of Humphrey Bogart, and in Classe tous risques a young louche named Éric Stark. The film’s director, Claude Sautet, was thirty-six at the time, having apprenticed for years as an assistant director of middling, prefab projects—George Franju’s Eyes Without a Face (1960), which Sautet cowrote, being a key exception. Sautet is mostly an unknown quantity in anglophone circles and Classe tous risques is probably his most recognizable achievement thanks to the Criterion Collection, which gave it one of its comprehensive DVD treatments in 2008.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Wednesday Poem

THE ORIGIN OF LIGHT

to stand, he understood, but it was dark.

by Jack Coulehan

from Rattle Magazine

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Birth Of Naturalism

Peter Harrison at Aeon Magazine:

Leaving aside these associations with Western triumphalism, Huxley’s version of history, in which supernaturalism is engaged in an enduring struggle with naturalism, suffers from two fatal flaws. First, past historical actors, and indeed many non-Western cultures, observe no clear distinction between the natural and the supernatural. Second, and somewhat paradoxically, religious assumptions about the way in which nature is ordered turn out to have been crucial to the emergence of a naturalistic outlook.

Leaving aside these associations with Western triumphalism, Huxley’s version of history, in which supernaturalism is engaged in an enduring struggle with naturalism, suffers from two fatal flaws. First, past historical actors, and indeed many non-Western cultures, observe no clear distinction between the natural and the supernatural. Second, and somewhat paradoxically, religious assumptions about the way in which nature is ordered turn out to have been crucial to the emergence of a naturalistic outlook.

To most modern Westerners, the natural/supernatural distinction seems obvious and, well, natural. Yet, a few historians and social scientists have provided intimations of its historical and cultural novelty. In his classic book The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life (1912), the sociologist Émile Durkheim attempted to arrive at a definition of religion that fitted all of the relevant phenomena. He dispensed with the common assumption that ‘belief in supernatural beings’ was an essential component of religion, pointing out that ‘the idea of the supernatural arrived only yesterday.’ It has become increasingly apparent that Durkheim was understating the case: in most traditional cultures, the idea of the supernatural never arrived at all.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Tuesday, February 4, 2025

“The Blessed Curse” by Sarmad Sehbai, Reviewed

Prashant Keshavmurthy in the Asian Review of Books:

Fifteen years into his marriage, Noor Mohammad Ganju has never seen his wife naked. He lusts after her but sex, when she occasionally obliges him, is reduced by veils—literal and symbolic—to tedious and unimaginative coupling in the dark.

Fifteen years into his marriage, Noor Mohammad Ganju has never seen his wife naked. He lusts after her but sex, when she occasionally obliges him, is reduced by veils—literal and symbolic—to tedious and unimaginative coupling in the dark.

Negotiating with multiple folds of crumpled sheets, he would wander through the fluffy confusion, etching a figure in his mind, reading zips and buttons … At last, she would let him pull her shalwar half down and he would perform a missionary in her midwife position; a pantomime of awkward limbs and dull weight.

This early passage sets the tone for Sarmad Sehbai’s novel The Blessed Curse that, in 25 relatively short and vivid chapters, tells the increasingly absurdist story of the lengths to which a politically and militarily powerful trio of men will go to swell their ever-flagging male potency. The country is never named but is recognizably Sehbai’s home nation of Pakistan in which he has been, since the 1970s, esteemed as a poet and playwright in Urdu and Punjabi and as head of PTV’s theater department.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The End of Search, The Beginning of Research

Ethan Mollick at One Useful Thing:

A hint to the future arrived quietly over the weekend. For a long time, I’ve been discussing two parallel revolutions in AI: the rise of autonomous agents and the emergence of powerful Reasoners since OpenAI’s o1 was launched. These two threads have finally converged into something really impressive – AI systems that can conduct research with the depth and nuance of human experts, but at machine speed. OpenAI’s Deep Research demonstrates this convergence and gives us a sense of what the future might be. But to understand why this matters, we need to start with the building blocks: Reasoners and agents.

A hint to the future arrived quietly over the weekend. For a long time, I’ve been discussing two parallel revolutions in AI: the rise of autonomous agents and the emergence of powerful Reasoners since OpenAI’s o1 was launched. These two threads have finally converged into something really impressive – AI systems that can conduct research with the depth and nuance of human experts, but at machine speed. OpenAI’s Deep Research demonstrates this convergence and gives us a sense of what the future might be. But to understand why this matters, we need to start with the building blocks: Reasoners and agents.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

How does fear influence our relationships, art, and even our values?

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Rachel Cusk’s ‘Parade’

Jessica Swoboda at Commonweal:

Reading a Rachel Cusk novel is like watching a recording of your everyday life, with all your subtly unflattering habits, traits, and actions. A conversation with your seatmate on a plane reveals that you manipulate your family like items on an Excel sheet. A lunch meeting about a potential business partnership discloses that people only matter to you if you profit from them. No one at your get-together of acquaintances reacts when a woman admits she abuses her dog.

Reading a Rachel Cusk novel is like watching a recording of your everyday life, with all your subtly unflattering habits, traits, and actions. A conversation with your seatmate on a plane reveals that you manipulate your family like items on an Excel sheet. A lunch meeting about a potential business partnership discloses that people only matter to you if you profit from them. No one at your get-together of acquaintances reacts when a woman admits she abuses her dog.

These are references to scenes from Cusk’s acclaimed Outline trilogy (2014–18), novels driven by a series of exchanges that Faye, the mostly mute narrator, has with those she encounters. Her conversations read more like monologues, the characters talking at her like she’s on a bad date. These quasi-vignettes replace a traditional narrative arc. The characters don’t have rich inner lives, and they’re largely indistinguishable, different only in the ways that their greed, narcissism, and self-centeredness manifest. As a narrator, Faye is deadpan, sometimes even cruel; she allows no wrongdoing, misstep, or embarrassment to go unnoticed

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

A road forward for the center left

Matt Lutz at Persuasion:

Left-wing activists benefit from a framework where “center left” just means “whatever the left says, but less,” because this gives them the power to alter what it means to be on the center left just by advocating for more extreme views. If the left gets more extreme, the center left must follow them at least part of the way, or risk being labeled as “on the right.” That can be an effective rhetorical cudgel against those who care about being “on the left.” And it raises the question: If your position is that you support what we do (just less), why not go all the way? Not only does this framework provide too much power to activists, it also harms the electoral prospects of center-left political parties, like the Democrats. If the best account the Democrats can give of their stance on cultural issues is “Whatever activists say, but less,” they’re setting themselves up for defeat. That message alienates everyone.

Left-wing activists benefit from a framework where “center left” just means “whatever the left says, but less,” because this gives them the power to alter what it means to be on the center left just by advocating for more extreme views. If the left gets more extreme, the center left must follow them at least part of the way, or risk being labeled as “on the right.” That can be an effective rhetorical cudgel against those who care about being “on the left.” And it raises the question: If your position is that you support what we do (just less), why not go all the way? Not only does this framework provide too much power to activists, it also harms the electoral prospects of center-left political parties, like the Democrats. If the best account the Democrats can give of their stance on cultural issues is “Whatever activists say, but less,” they’re setting themselves up for defeat. That message alienates everyone.

To resist this dynamic, those on the center left must defend a positive vision of what it means to be on the center left. To that end, here are three principles that can provide a unifying framework:

- Liberalism is the first principle.

- Inequalities are problems to be solved.

- Absolutes are unwise.

I don’t pretend that any of these ideas are novel. But they’re no less important for being familiar. Let’s look at them in more depth.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

William Kentridge on Picasso, Goya, and Others

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Silent Catastrophes: Essays in Austrian Literature

Ritchie Robertson at Literary Review:

Why Austrian literature? Sebald was not Austrian, though his south German birthplace, Wertach, was within walking distance of the Austrian border. Austrian literature appealed to his feeling for marginality. Its major writers, from Franz Grillparzer via Arthur Schnitzler, Hugo von Hofmannsthal and Kafka to Peter Handke, do not fit easily into the pattern of German literature, stretching from Goethe via Thomas Mann to Günter Grass. They excel, in Sebald’s view, in exploring psychological states ranging from obsession and melancholia to schizophrenic breakdown. One notably empathetic essay concerns an actual schizophrenic, Ernst Herbeck (1920–91), who was confined for fifty years in a mental hospital near Klosterneuburg, north of Vienna, where Sebald visited him. Herbeck wrote a large number of poems with enigmatic lines, such as ‘the raven leads the pious on’. Although these poems yield nothing to academic exegesis, they not only linger in the memory but may also, Sebald suggests, reveal the primitive processes through which poetic language arises.

Why Austrian literature? Sebald was not Austrian, though his south German birthplace, Wertach, was within walking distance of the Austrian border. Austrian literature appealed to his feeling for marginality. Its major writers, from Franz Grillparzer via Arthur Schnitzler, Hugo von Hofmannsthal and Kafka to Peter Handke, do not fit easily into the pattern of German literature, stretching from Goethe via Thomas Mann to Günter Grass. They excel, in Sebald’s view, in exploring psychological states ranging from obsession and melancholia to schizophrenic breakdown. One notably empathetic essay concerns an actual schizophrenic, Ernst Herbeck (1920–91), who was confined for fifty years in a mental hospital near Klosterneuburg, north of Vienna, where Sebald visited him. Herbeck wrote a large number of poems with enigmatic lines, such as ‘the raven leads the pious on’. Although these poems yield nothing to academic exegesis, they not only linger in the memory but may also, Sebald suggests, reveal the primitive processes through which poetic language arises.

Herbeck’s poems are at the furthest distance from the modern, bureaucratic, administered world which Sebald, like the Frankfurt School, wanted to resist. He traces its development in 19th-century bourgeois literature, in which Enlightenment reason is converted into prescriptive rationality, and emotional and erotic impulses are subjected to the discipline of bourgeois marriage.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

7 Big Questions About Cancer, Answered

Nina Agrawal in The New York Times:

Every day, billions of cells in our body divide or die off. It’s all part of the intricate processes that keep blood flowing from our heart, food moving through our gut and our skin regenerating. Once in a while, though, something goes awry, and cells that should stop growing or die simply don’t. Left unchecked, those cells can turn into cancer.

Every day, billions of cells in our body divide or die off. It’s all part of the intricate processes that keep blood flowing from our heart, food moving through our gut and our skin regenerating. Once in a while, though, something goes awry, and cells that should stop growing or die simply don’t. Left unchecked, those cells can turn into cancer.

The question of when and why, exactly, that happens — and what can be done to stop it — has long stumped cancer scientists and physicians. Despite the unanswered questions that remain, they have made enormous strides in understanding and treating cancer.

“We’re a lot less fearful about telling patients what we do and don’t know, because we know a lot more,” said Dr. George Demetri, senior vice president for experimental therapeutics at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston.

Here are some of the biggest questions about cancer that scientists have started to answer.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

A Short History of Black Labor Movements in America

Emma Fridy in Louisville Review:

Born out of necessity, America’s Black labor movements have left an indelible mark upon the social fabric of our country. For hundreds of years Black activists have poured blood, sweat, and tears into organizing the American labor force for better working conditions. Until relatively recently, Black Americans were excluded from major unions, and therefore had to create separate institutions that fought for Black workers. Black men organized against all odds in the agriculture sector, and Black women, who were often excluded from leadership and sometimes even membership in other Black organizations, were early proponents of labor reform by unionizing domestic workers. As civil rights in America progressed, major unions integrated and partnered with Black labor movements across America to champion both economic reform and racial justice. Today, union membership in the Black community is declining despite the long tradition of Black-led labor activism.

Born out of necessity, America’s Black labor movements have left an indelible mark upon the social fabric of our country. For hundreds of years Black activists have poured blood, sweat, and tears into organizing the American labor force for better working conditions. Until relatively recently, Black Americans were excluded from major unions, and therefore had to create separate institutions that fought for Black workers. Black men organized against all odds in the agriculture sector, and Black women, who were often excluded from leadership and sometimes even membership in other Black organizations, were early proponents of labor reform by unionizing domestic workers. As civil rights in America progressed, major unions integrated and partnered with Black labor movements across America to champion both economic reform and racial justice. Today, union membership in the Black community is declining despite the long tradition of Black-led labor activism.

More here. (Note: In honor of Black History Month, at least one post will be devoted to its 2025 theme of “African Americans and Labor” throughout the month of February)

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Tuesday Poem

Border

I’m going to move ahead.

Behind me my whole family is calling,

My child is pulling my sari-end,

My husband stands blocking the door,

But I will go.

There’s nothing ahead but a river.

I will cross.

I know how to swim,

but they won’t let me swim, won’t let me cross.

There’s nothing on the other side of the river

but a vast expanse of fields,

But I’ll touch this emptiness once

and run against the wind, whose whooshing sound

makes me want to dance.

I’ll dance someday

and then return.

I’ve not played keep-away for years

as I did in childhood.

I’ll raise a great commotion playing keep-away someday

and then return.

For years I haven’t cried with my head

in the lap of solitude.

I’ll cry to my heart’s content someday

and then return.

There’s nothing ahead but a river,

and I know how to swim.

Why shouldn’t I go?

I’ll go.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Monday, February 3, 2025

Trump starts to break things

Noah Smith at Noahpinion:

Before the election, I wrote a whole bunch of posts about why it was a bad idea to elect Donald Trump. But sadly, America elected him anyway. After he won, I wrote a post outlining a best-case scenario for Trump’s second term. The optimistic scenario was that Trump’s threats to enact harmful policies and cause chaos were mostly bluster, and that in the end he’d end up just waging a bunch of culture wars instead of wrecking the economy and gutting U.S. institutions.

Before the election, I wrote a whole bunch of posts about why it was a bad idea to elect Donald Trump. But sadly, America elected him anyway. After he won, I wrote a post outlining a best-case scenario for Trump’s second term. The optimistic scenario was that Trump’s threats to enact harmful policies and cause chaos were mostly bluster, and that in the end he’d end up just waging a bunch of culture wars instead of wrecking the economy and gutting U.S. institutions.

We’re only two weeks into Trump’s presidency, and that optimistic scenario is looking more and more remote by the day. Trump is creating a lot of institutional chaos, and I’ll talk about that in a bit. Today I’m going to talk about Trump’s main economic policy: tariffs.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Collapse of Ego Depletion

Michael Inzlicht at Speak Now, Regret Later:

In the winter of 2015, I stood before the largest gathering of social psychologists in the world to accept one of the field’s highest honours. My collaborators and I were being celebrated for our theory about willpower—a theory I’d spent many years refining. For a kid who grew up with empty bookshelves, this should have been a moment of triumph [1].

In the winter of 2015, I stood before the largest gathering of social psychologists in the world to accept one of the field’s highest honours. My collaborators and I were being celebrated for our theory about willpower—a theory I’d spent many years refining. For a kid who grew up with empty bookshelves, this should have been a moment of triumph [1].

Instead, I felt like a fraud.

At that same conference, I had to confront an uncomfortable truth: the foundation of our celebrated paper was crumbling. Ego depletion—the once-famous idea that self-control relies on a finite resource that can be depleted through use—wasn’t real. That award? It was like winning a Nobel prize for developing the frontal lobotomy as a treatment for mental illness; and, yes, that really happened.

This isn’t just another story about failed replications or p-hacking (though those shenanigans will make an appearance). It’s a story about what happens when we fall in love with our theories more than the truth. The replication crisis didn’t just shake the foundations of psychology; it shook those of us who had built our careers on ideas that no longer held up to scrutiny.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.