David Enrich in the New York Times:

After a financial crisis torpedoed the U.S. economy in 2008, the public clamored for accountability. Millions had lost their homes and livelihoods. Crimes had been committed. Surely, the bankers, brokers and investors who had precipitated and profited from this collapse would be brought to justice.

Nope. While a few midlevel bank employees were prosecuted, the architects of a rotten system generally escaped with their nine-figure fortunes intact. It was not long afterward that Donald Trump began his rise to power, and many observers pointed to the hangover from the 2008 crisis, and the impunity that characterized it, as part of his appeal.

In “The Killing Fields of East New York,” Stacy Horn examines another, long forgotten financial crisis — one with a very different outcome.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

‘Big Steve,’ his students called him. Steven Weinberg was not physically imposing, but was an intellectually dominant and much-revered figure in the scientific community and on the public stage. One of the most distinguished theoretical physicists of the past 75 years, Weinberg dedicated his professional life to leading what he described as the ‘grand enterprise’ of seeking the bedrock laws of nature that underpin the workings of the Universe. He looked the part, too — at physics conferences, he was often the only participant wearing a suit and tie.

‘Big Steve,’ his students called him. Steven Weinberg was not physically imposing, but was an intellectually dominant and much-revered figure in the scientific community and on the public stage. One of the most distinguished theoretical physicists of the past 75 years, Weinberg dedicated his professional life to leading what he described as the ‘grand enterprise’ of seeking the bedrock laws of nature that underpin the workings of the Universe. He looked the part, too — at physics conferences, he was often the only participant wearing a suit and tie. A few weeks ago I

A few weeks ago I  One story

One story Did you know your gut microbiome can impact various aspects of your health—including your mental and

Did you know your gut microbiome can impact various aspects of your health—including your mental and  But the problem with advice is not conceptual. Atwood’s disappointed acolytes were hoping not for a kind of guidance that is analytically impossible but for one that is merely in severe decline.

But the problem with advice is not conceptual. Atwood’s disappointed acolytes were hoping not for a kind of guidance that is analytically impossible but for one that is merely in severe decline. The second hour of “Gone with the Wind,” the bold, almost brazenly romantic Civil War epic that won ten Academy Awards, is largely a portrait of hell. “The skies rained death,” the screen reads. General William Tecumseh Sherman and his Union Army have brutally taken Atlanta during a hard-fought campaign, at a combined cost of nearly seventy-five thousand casualties. Scarlett O’Hara, a wealthy white Southerner, picks her way out of the city, passing the littered remains of wagons and men while vultures hover overhead. All the plantation houses she sees have been reduced to charred ruins.

The second hour of “Gone with the Wind,” the bold, almost brazenly romantic Civil War epic that won ten Academy Awards, is largely a portrait of hell. “The skies rained death,” the screen reads. General William Tecumseh Sherman and his Union Army have brutally taken Atlanta during a hard-fought campaign, at a combined cost of nearly seventy-five thousand casualties. Scarlett O’Hara, a wealthy white Southerner, picks her way out of the city, passing the littered remains of wagons and men while vultures hover overhead. All the plantation houses she sees have been reduced to charred ruins. O

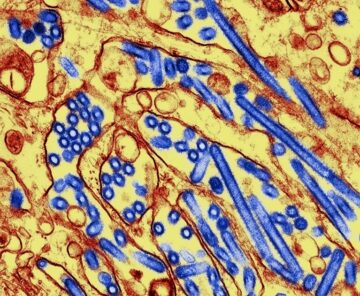

O Ten months on from the shocking discovery that a virus usually carried by wild birds

Ten months on from the shocking discovery that a virus usually carried by wild birds

…As for putting on the airs of religion and spirituality, this is probably both the saddest and desperate pose of all and one, if you are a believer, that perilously approaches blasphemy in its violation of the 3rd commandment: “Thou shalt not take the name of the Lord thy God in vain.”No wonder then that despite all the holy muttering there is no hint of the pathos and depth that can be conveyed by genuine religious art and sentiment even to sensitive non-believers. It is more spiritually sterile than the secular world it reviles.

…As for putting on the airs of religion and spirituality, this is probably both the saddest and desperate pose of all and one, if you are a believer, that perilously approaches blasphemy in its violation of the 3rd commandment: “Thou shalt not take the name of the Lord thy God in vain.”No wonder then that despite all the holy muttering there is no hint of the pathos and depth that can be conveyed by genuine religious art and sentiment even to sensitive non-believers. It is more spiritually sterile than the secular world it reviles. In 2009, Jonathan Weissman was hunting for a new way to spy on

In 2009, Jonathan Weissman was hunting for a new way to spy on  Robert Eggers’s new version of Nosferatu is not my favorite contemporary vampire movie (that would have to be Ana Lily Amipour’s A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night [2014]), or even my favorite Eggers film. The Lighthouse (2019), an extraordinary and idiosyncratic nightmare, is probably more true to Murnau’s Expressionist ideals, and the sublime potential of the Gothic, than this remake. For the first hour I didn’t know why Nosferatu was being remade at all – surely this was a mistaken project from the beginning since Murnau’s inimitable 1922 classic remains incorruptible from beyond the grave. As the second half of the film unfolded into abject madness, and afterwards thinking through the film with friends, however, Eggers’s Nosferatu has stayed with me, its shadows deepening as its various challenges to its predecessors have seeped into the frame.

Robert Eggers’s new version of Nosferatu is not my favorite contemporary vampire movie (that would have to be Ana Lily Amipour’s A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night [2014]), or even my favorite Eggers film. The Lighthouse (2019), an extraordinary and idiosyncratic nightmare, is probably more true to Murnau’s Expressionist ideals, and the sublime potential of the Gothic, than this remake. For the first hour I didn’t know why Nosferatu was being remade at all – surely this was a mistaken project from the beginning since Murnau’s inimitable 1922 classic remains incorruptible from beyond the grave. As the second half of the film unfolded into abject madness, and afterwards thinking through the film with friends, however, Eggers’s Nosferatu has stayed with me, its shadows deepening as its various challenges to its predecessors have seeped into the frame. B

B Other than fairy tales — which were, by and large, originally compiled for adult audiences — children’s literature from the past holds little of interest for children today. Consider one of the earliest known examples of a book targeted at children, James Janeway’s A Token for Children from 1671. A typical story in this collection tells us how young a child was when he memorized the catechism, how passionately he cared for the souls of his brothers and sisters, and how obedient and respectful he was with his elders. It might quote at length from one of his prayers and end by describing his peaceful death from the plague at the age of 10. Every story in Token ends in this way, with a boy or girl rewarded for his or her piety with a happy early death.

Other than fairy tales — which were, by and large, originally compiled for adult audiences — children’s literature from the past holds little of interest for children today. Consider one of the earliest known examples of a book targeted at children, James Janeway’s A Token for Children from 1671. A typical story in this collection tells us how young a child was when he memorized the catechism, how passionately he cared for the souls of his brothers and sisters, and how obedient and respectful he was with his elders. It might quote at length from one of his prayers and end by describing his peaceful death from the plague at the age of 10. Every story in Token ends in this way, with a boy or girl rewarded for his or her piety with a happy early death.