Sensual

The word “sensual” is not intended to bring to mind

quivering dusky maidens or priapic black studs.

I refer to something much simpler and much less

fanciful. To be sensual, is to respect and rejoice in

the force of life, of life itself, and to be present

in all that one does, from the effort of loving to the

breaking of bread.

Something very sinister happens to the people of a

country when they begin to mistrust their own

reactions as they do here, and become joyless

as they as they have become. It is this individual

uncertainty on the part of white American men and

women, this inability to renew themselves at the

fountain of their own lives, that makes the discussion,

of any conundrum—any reality, so supremely difficult.

The person who distrusts himself has no touchstone

for reality— for this touchstone can only be oneself.

Such a person puts between himself and reality nothing

less than a labyrinth of attitudes, historical and public,

that do not relate to the present any more than they

relate to the person. Therefore, whatever white people

do not know about Negroes reveals, precisely what they

do not know about themselves.

by James Baldwin

from The Fire Next Time

Dell Publishing, New York, 1962

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

For Kristian Cook, every pizza box he opened was another door closed on the path to overcoming obesity. “I had massive cravings for pizza,” he says. “That was my biggest downfall.” At 114 kilograms and juggling a daily regimen of medications for high cholesterol, hypertension and gout, the New Zealander resolved to take action. In late 2022, at the age of 46, Cook joined a clinical trial that set out to test a combination of the

For Kristian Cook, every pizza box he opened was another door closed on the path to overcoming obesity. “I had massive cravings for pizza,” he says. “That was my biggest downfall.” At 114 kilograms and juggling a daily regimen of medications for high cholesterol, hypertension and gout, the New Zealander resolved to take action. In late 2022, at the age of 46, Cook joined a clinical trial that set out to test a combination of the  Women have always had a special relationship with lies; often, we have relied on them for survival. But it was the aspirational feminism of the 2010s—individualistic, empowering, breathless, especially after SoulCycle—which first introduced many of us to the art of lying to ourselves.

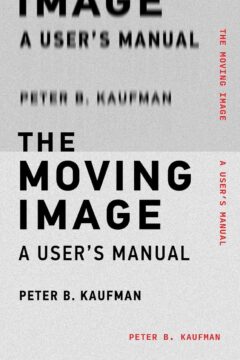

Women have always had a special relationship with lies; often, we have relied on them for survival. But it was the aspirational feminism of the 2010s—individualistic, empowering, breathless, especially after SoulCycle—which first introduced many of us to the art of lying to ourselves. QUIETLY, ALMOST ELUSIVELY, video has become the dominant medium of human communication. There are hundreds of billions of cameras out in the world filming as you’re reading this article. Two-thirds of global internet traffic is video; that number continues to climb. If we date print back to 1455 and

QUIETLY, ALMOST ELUSIVELY, video has become the dominant medium of human communication. There are hundreds of billions of cameras out in the world filming as you’re reading this article. Two-thirds of global internet traffic is video; that number continues to climb. If we date print back to 1455 and  In a column for The Point magazine, Agnes Callard, a philosopher and professor at the University of Chicago, comes out against advice. She makes her case using an anecdote involving the novelist Margaret Atwood. Asked about her advice for a group of aspiring writers, Atwood is stumped and ends up offering little more than bromides encouraging them to write every day and try not to be inhibited. Callard excuses Atwood’s banality, blaming it on the fundamental incoherence of the thing she was asked to produce.

In a column for The Point magazine, Agnes Callard, a philosopher and professor at the University of Chicago, comes out against advice. She makes her case using an anecdote involving the novelist Margaret Atwood. Asked about her advice for a group of aspiring writers, Atwood is stumped and ends up offering little more than bromides encouraging them to write every day and try not to be inhibited. Callard excuses Atwood’s banality, blaming it on the fundamental incoherence of the thing she was asked to produce.

We were fortunate that during our tenures in office no effort was made to unlawfully undermine the nation’s financial commitments. Regrettably,

We were fortunate that during our tenures in office no effort was made to unlawfully undermine the nation’s financial commitments. Regrettably,  Black History Month is a time to reflect on the central role of Black people in shaping this nation. Nowhere is that more evident than the labor movement. A founding tenet of American capitalism and our economy is that Black bodies are worth more than Black minds. This belief is continually demonstrated by the value placed on Black workers and their work. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Black workers risked their lives in essential jobs to keep the country operating. And in doing so faced an

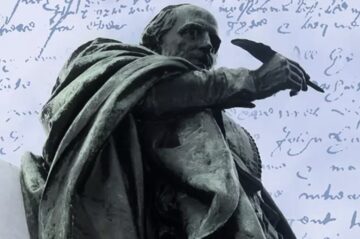

Black History Month is a time to reflect on the central role of Black people in shaping this nation. Nowhere is that more evident than the labor movement. A founding tenet of American capitalism and our economy is that Black bodies are worth more than Black minds. This belief is continually demonstrated by the value placed on Black workers and their work. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Black workers risked their lives in essential jobs to keep the country operating. And in doing so faced an  The most striking assertion in Wittgenstein’s critique of Shakespeare may be this, written in 1946: “Shakespeare’s similes are, in the ordinary sense, bad. So if they are nevertheless good – & I don’t know whether they are or not – they must be a law to themselves.” What makes Wittgenstein think he can lay claim to such a judgment? Part of the answer may lie in Wittgenstein’s own remarkable talent for similes and figures of comparison. Given their importance to his way of doing philosophy, it shouldn’t surprise that he was good at making them, and knew he was good.

The most striking assertion in Wittgenstein’s critique of Shakespeare may be this, written in 1946: “Shakespeare’s similes are, in the ordinary sense, bad. So if they are nevertheless good – & I don’t know whether they are or not – they must be a law to themselves.” What makes Wittgenstein think he can lay claim to such a judgment? Part of the answer may lie in Wittgenstein’s own remarkable talent for similes and figures of comparison. Given their importance to his way of doing philosophy, it shouldn’t surprise that he was good at making them, and knew he was good. I’m like a mechanic scrambling last-minute checks before Apollo 13 takes off. If you ask for my take on the situation, I won’t comment on the quality of the in-flight entertainment, or describe how beautiful the stars will appear from space.

I’m like a mechanic scrambling last-minute checks before Apollo 13 takes off. If you ask for my take on the situation, I won’t comment on the quality of the in-flight entertainment, or describe how beautiful the stars will appear from space. MIZDARKHAN, Uzbekistan — On a hill at the edge of the desert stands a wooden edifice above a simple tomb. It consists of four slanting poles that come together in a frame, inside of which are bundled sticks that resemble kindling. It seems a puzzling marker for a grave until you learn the legend of whose body lies inside: Gayōmart, the first human, neither woman nor man, who was created from mud by the Zoroastrian god Ahura Mazda. Zoroastrians venerate fire, so the structure makes sense. It is a symbolic beacon waiting for its flame.

MIZDARKHAN, Uzbekistan — On a hill at the edge of the desert stands a wooden edifice above a simple tomb. It consists of four slanting poles that come together in a frame, inside of which are bundled sticks that resemble kindling. It seems a puzzling marker for a grave until you learn the legend of whose body lies inside: Gayōmart, the first human, neither woman nor man, who was created from mud by the Zoroastrian god Ahura Mazda. Zoroastrians venerate fire, so the structure makes sense. It is a symbolic beacon waiting for its flame. Michel Pastoureau began his wonderful and widely translated series on the history of colours with Blue a quarter of a century ago. Black, Green, Red, Yellow and White followed and now here is a history of pink, which may not be ‘a color in its own right’ and for which neither Latin nor ancient Greek has a standard word (it was long regarded as a shade of red). Nevertheless, Pink is as sumptuous as its predecessors, printed on gorgeous glossy paper and written with impassioned scholarship.

Michel Pastoureau began his wonderful and widely translated series on the history of colours with Blue a quarter of a century ago. Black, Green, Red, Yellow and White followed and now here is a history of pink, which may not be ‘a color in its own right’ and for which neither Latin nor ancient Greek has a standard word (it was long regarded as a shade of red). Nevertheless, Pink is as sumptuous as its predecessors, printed on gorgeous glossy paper and written with impassioned scholarship. For the family, withdrawing or withholding life-sustaining treatments from a dying loved one, even if doctors advise that the treatment is unlikely to succeed or benefit the patient, can be overwhelming and painful. Studies show that their stress can be at the

For the family, withdrawing or withholding life-sustaining treatments from a dying loved one, even if doctors advise that the treatment is unlikely to succeed or benefit the patient, can be overwhelming and painful. Studies show that their stress can be at the