Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

Pink: The History of a Color

Norma Clarke at Literary Review:

Michel Pastoureau began his wonderful and widely translated series on the history of colours with Blue a quarter of a century ago. Black, Green, Red, Yellow and White followed and now here is a history of pink, which may not be ‘a color in its own right’ and for which neither Latin nor ancient Greek has a standard word (it was long regarded as a shade of red). Nevertheless, Pink is as sumptuous as its predecessors, printed on gorgeous glossy paper and written with impassioned scholarship.

Michel Pastoureau began his wonderful and widely translated series on the history of colours with Blue a quarter of a century ago. Black, Green, Red, Yellow and White followed and now here is a history of pink, which may not be ‘a color in its own right’ and for which neither Latin nor ancient Greek has a standard word (it was long regarded as a shade of red). Nevertheless, Pink is as sumptuous as its predecessors, printed on gorgeous glossy paper and written with impassioned scholarship.

When Isaac Newton broke white light down into coloured rays in 1666, he did not find pink. Orange and purple were there, along with red, yellow, green and blue, so for scientists those were the true colours. Yet pink was observable in nature – in plants, on the feathers of animals, in minerals and in the sky. Pink had begun to appear in dyes and paints in the 14th century – relatively late compared to other colours – and it rapidly became fashionable. A unique document, Prammatica del vestire, has survived to tell us about the wardrobes of all women of the wealthy classes living in Florence between 1343 and 1345.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

What the ‘moral distress’ of doctors tells us about eroding trust in health care

Daniel T. Kim at The Conversation:

For the family, withdrawing or withholding life-sustaining treatments from a dying loved one, even if doctors advise that the treatment is unlikely to succeed or benefit the patient, can be overwhelming and painful. Studies show that their stress can be at the same level as people who have just survived house fires or similar catastrophes.

For the family, withdrawing or withholding life-sustaining treatments from a dying loved one, even if doctors advise that the treatment is unlikely to succeed or benefit the patient, can be overwhelming and painful. Studies show that their stress can be at the same level as people who have just survived house fires or similar catastrophes.

While making such high-stakes decisions, families need to be able to trust their doctor’s information; they need to be able to believe that their recommendations come from genuine empathy to serve only the patient’s interests. This is why prominent bioethicists have long emphasized trustworthiness as a central virtue of good clinicians.

However, the public’s trust in medical leaders has been on a precipitous decline in recent decades. Historical polling data and surveys show that trust in physicians is lower in the U.S. than in most industrialized countries. A recent survey from Sanofi, a pharmaceutical company, found that mistrust of the medical system is even worse among low-income and minority Americans, who experience discrimination and persistent barriers to care.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Media Spawned McCarthyism. Now History Is Repeating Itself

A. Brad Schwartz in Time Magazine:

Donald Trump’s return to the White House has plunged Washington into upheaval and anxiety, bringing loyalty tests and other efforts to purge government employees. This climate of fear recalls the anticommunist paranoia of the 1950s and its crucial turning point exactly 75 years ago—when a famous speech, based on a lie, catapulted a little-known politician to prominence and added a new word to the American lexicon: McCarthyism. With that speech, Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy seized the nation’s attention and would hold it for four years. Yet his words probably would have faded into obscurity if reporters hadn’t amplified and reinforced them — despite knowing they were false. The story of the speech offers a dire warning for the present, because it demonstrates how elevating the false claims of elected officials can distort American politics to catastrophic effect.

Donald Trump’s return to the White House has plunged Washington into upheaval and anxiety, bringing loyalty tests and other efforts to purge government employees. This climate of fear recalls the anticommunist paranoia of the 1950s and its crucial turning point exactly 75 years ago—when a famous speech, based on a lie, catapulted a little-known politician to prominence and added a new word to the American lexicon: McCarthyism. With that speech, Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy seized the nation’s attention and would hold it for four years. Yet his words probably would have faded into obscurity if reporters hadn’t amplified and reinforced them — despite knowing they were false. The story of the speech offers a dire warning for the present, because it demonstrates how elevating the false claims of elected officials can distort American politics to catastrophic effect.

…The senator asserted that five years after winning World War II, the U.S. was losing around the globe, locked in a struggle with communism that seemed destined to end in nuclear conflict. The blame for this terrifying scenario, McCarthy declared, rested with traitorous federal employees, who had sold their country out and had to be purged from its service. Near the end of his remarks, the senator made a more specific claim about the enemy within.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

White People Have a Very Very Serious Problem

More here. (Note: In honor of Black History Month, at least one post will be devoted to its 2025 theme of “African Americans and Labor” throughout the month of February)

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sunday, February 9, 2025

Susan Alcorn (1953 – 2025) Composer and Pedal Steel Player

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Morton Künstler (1931 – 2025) Painter

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Is Agnes Callard Making You Uncomfortable?

Laura Kipnis in TNR:

The non-modest mission of her sprightly new book, Open Socrates: The Case for a Philosophical Life, is to develop a strand of ethical thought that she labels “Neo-Socratic,” and which departs entirely from the prevailing ethical systems of Kant, Mill, and Aristotle. Among the challenges of the project, she notes, is that Socrates was content to refute everyone else’s positions while affirming nothing concrete himself, meaning that his philosophical heirs do a lot of performative contradiction, which is not sufficient. Nor is what we like to call “the Socratic method”—teaching by asking questions until students produce the correct answers—what Socrates had in mind. Such attempts to mimic him miss the point, which is that true thinking should be dangerous to your intellectual equilibrium. It should strive for answers that overthrow the terms of the questions being asked, not simply prove a point.

The non-modest mission of her sprightly new book, Open Socrates: The Case for a Philosophical Life, is to develop a strand of ethical thought that she labels “Neo-Socratic,” and which departs entirely from the prevailing ethical systems of Kant, Mill, and Aristotle. Among the challenges of the project, she notes, is that Socrates was content to refute everyone else’s positions while affirming nothing concrete himself, meaning that his philosophical heirs do a lot of performative contradiction, which is not sufficient. Nor is what we like to call “the Socratic method”—teaching by asking questions until students produce the correct answers—what Socrates had in mind. Such attempts to mimic him miss the point, which is that true thinking should be dangerous to your intellectual equilibrium. It should strive for answers that overthrow the terms of the questions being asked, not simply prove a point.

The failure to be sufficiently or dangerously philosophical besets most academic philosophers, she charges, who take off their philosopher hats when they arrive home after teaching their classes, shielding their lives from the kinds of inquiries that might disrupt their comfortable existences. They’re afraid of philosophy, and not actually doing it.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

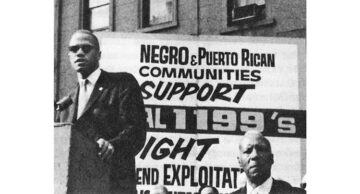

Leader of working people of all colors and creeds

Naomi Craine in The Militant:

During the last year of his life, Malcolm organized and spoke with increasing clarity on questions that remain central for working people today.

During the last year of his life, Malcolm organized and spoke with increasing clarity on questions that remain central for working people today.

“I believe that there will ultimately be a clash between the oppressed and those that do the oppressing,” he told a television reporter in 1965. “I believe that there will be a clash between those who want freedom, justice, and equality for everyone and those who want to continue the systems of exploitation. I believe that there will be that kind of clash, but I don’t think that it will be based upon the color of the skin, as Elijah Muhammad had taught it.”

Malcolm acted on his conviction that the fight to end racial oppression here was part of the worldwide struggle against colonialism and imperialism. He met and worked with other revolutionaries, taking two extended trips to Africa and the Middle East. He was attracted to the workers and farmers governments that had come to power through popular revolutions in Algeria and Cuba.

He was drawn to work with the Socialist Workers Party in the U.S.

Speaking at a Militant Labor Forum in New York in May 1964, Malcolm pointed to the example set by the Chinese and Cuban revolutions, where the capitalists and landlords had been expropriated. In contrast, he said, “The system in this country cannot produce freedom for an Afro-American. It is impossible for this system, this economic system, this political system, this social system, this system, period.”

More here. (Note: In honor of Black History Month, at least one post will be devoted to its 2025 theme of “African Americans and Labor” throughout the month of February)

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sunday Poem

The Herd

The herd is so vitally important for the individual

that their views, beliefs, feelings, constitute reality

more so than what his senses and his reason tell him.

For the majority of people, their identity is precisely

rooted in conformity with social clichés: “They”

are who they are supposed to be, hence fear

of ostracism implies fear of loss of identity,

and the combination of both has a most

powerful effect.

Ability to act according to one’s conscience

depends upon the degree to which one has

transcended the limits of one’s society and

become a citizen of the world.

by Eric Fromm

from Poetic Outlaws

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Is it all about power?

LuHan Gabel in The Ideas Letter:

The Japanese feminist Chizuko Ueno begins her book, The Ideology In Order to Survive, with an anecdote. In 1994, Ueno attended an international conference organized by the Japanese progressive journal Sekai and the French magazine Le Monde Diplomatique. At the end of the conference, a French speaker asked the audience: “Human rights is a concept that originated in France. Do you think it is universal?”

“This is a tricky question to answer,” Ueno thought to herself. “If we answered yes, that means ‘you people in Asia also accept this French concept.’ And it also means to acknowledge French universalism. But if we answered no, that could mean ‘Asians are such un-enlightened people who can’t even accept the concept of human rights.’”

After some pondering, however, Ueno thought of a better response: “Human rights is a special French concept. It claims to be universal, but it cannot reach the level of universality it claims, precisely because the West has had monopoly on it.”

Much has changed in the ensuing 30 years since this debate took place. I can imagine the French speaker in this story now asking herself the same question as Nicholas Bequelin does in his recent Ideas Letter piece: “Can human rights survive the decline of global Western hegemony?”

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

China’s Long Economic Slowdown

Ho-fung Hung in Dissent:

The China boom has ended. The country’s annual economic growth rate has decelerated from a height of more than 14 percent in 2007 to less than 6 percent in 2023. Total indebtedness (including both internal and external debt) surpassed an alarming 365 percent of GDP as of the first quarter of 2024, according to the Institute of International Finance—much higher than comparable middle-income countries like Brazil (208 percent), Argentina (152 percent), and Indonesia (86 percent). The collapse or near collapse of real estate giants like Evergrande, which just a few years ago was the poster child for China’s economic miracle, is just one example of the country’s economic difficulties.

Over the last three decades, China has experienced multiple economic crises driven by domestic imbalances or external shocks, including overheating in 1992–93, deflation in the aftermath of the 1997–98 Asian financial crisis, and fallout from the global financial crisis of 2008. Each time, the Chinese economy turned around swiftly thanks to decisive policy adjustments (Zhu Rongji’s reforms in 1994), new openings to trade (the 2001 accession to the WTO), and aggressive financial stimulus (the 2009–10 state-driven investment spree). These past successes have led many China watchers to assume the Chinese government can repeat the magic and rejuvenate the economy once again. But China’s current economic crisis has resulted from a long and deep structural imbalance that will be much more difficult to resolve.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Gold, volk and IQs: Hayek’s fatal conceit

Branko Milanovic over at his substack:

One has to admire Quinn Slobodan: in order to write his most recent book “Hayek’s bastards: The neoliberal roots of the populist right” (the title is modeled after “Voltaire’s bastards” by John Ralston Saul), he had to enter the world of madmen who produced movies, fictionalized novels, investment newsletters, and comic books detailing the forthcoming economic apocalypse (several apocalypses every year for half a century), invraisemblable conspiracies and own racial superiority. All of that was happening because the piles of money were paid by various tycoons to maintain in a comfortable lifestyle and publishing activity Mont Pelerin Society fellows, so that they could continue meeting each other and exchanging the predictions of doom and gloom in the luxury hotels of the Riviera, Alpine resorts and even on the Galapagos islands.

The reader is unsure if this is really a world of madmen or the world of smart people who pretend to be madmen in order to extract money from the self-interested oligarchs and credulous readers (so called “investors”) who subscribe to their investment newsletters. One has a strong felling of a con business, reminiscent of evangelical scandals where preachers call for humility and love while the real business is one of money.

Did it have to be so? Friedrich Hayek is a serious thinker. Did his writings empower madmen who in many ways distorted his thinking (I will come to that later)?

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Slashing the State

Pablo Pryluka in Phenomenal World:

Javier Milei’s rise to the presidency of Argentina came with all sorts of promises for economic, political and cultural repair. In one campaign speech in the run up to the October 2023 election, Milei claimed that should his party, La Libertad Avanza (Liberty Advances), come to power, “Argentina could reach living standards similar to those of Italy or France in fifteen years. If you give me twenty years,” he went on, “Germany. And if you give me thirty-five years, the United States.” When he did in fact come into office in December of that year, he did so with a bold political agenda but little congressional support; La Libertad Avanza won just 15 percent of seats in the Cámara de Diputados and 10 percent in the Senate, both of which remained dominated by Peronists on the one side and Juntos por el Cambio (Together for Change), the coalition that led Mauricio Macri to the presidency in 2015, on the other. The promises had been large but, though victorious, Milei had been granted a tight space in which to maneuver.

Milei’s popularity was premised on his reputation as a staunch market radical and his apparent position against Argentina’s political elite. In presidential debates, he warned against “the damned caste” that, he claimed, “in fifty years would turn Argentina into the biggest slum in the world.” Corrupt politicians were keeping the public hooked on state handouts so as to keep themselves elected. In turn, the system produced budgetary deficits that led to rising debt or excessive money printing, driving inflation and economic collapse.

The solution he proposed was a radical deregulation of the economy, focusing on a reduction in public spending and taxes.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Gene Barge (1926 – 2025) Saxophonist

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Friday, February 7, 2025

Why AI Is A Philosophical Rupture

Tobias Rees at Noema:

Tobias Rees, founder of an AI studio located at the intersection of philosophy, art and technology, sat down with Noema Editor-in-Chief Nathan Gardels to discuss the philosophical significance of generative AI.

Tobias Rees, founder of an AI studio located at the intersection of philosophy, art and technology, sat down with Noema Editor-in-Chief Nathan Gardels to discuss the philosophical significance of generative AI.

Nathan Gardels: What remains unclear to us humans is the nature of machine intelligence we have created through AI and how it changes our own understanding of ourselves. What is your perspective as a philosopher who has contemplated this issue not from within the Ivory Tower, but “in the wild,” in the engineering labs at Google and elsewhere?

Tobias Rees: AI profoundly challenges how we have understood ourselves.

Why do I think so?

We humans live by a large number of conceptual presuppositions. We may not always be aware of them — and yet they are there and shape how we think and understand ourselves and the world around us. Collectively, they are the logical grid or architecture that underlies our lives.

What makes AI such a profound philosophical event is that it defies many of the most fundamental, most taken-for-granted concepts — or philosophies — that have defined the modern period and that most humans still mostly live by. It literally renders them insufficient, thereby marking a deep caesura.

Let me give a concrete example.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Neurological Roots of ‘Sinful’ Behavior

Emily Cataneo at Undark:

In “Seven Deadly Sins,” Leschziner, a neurologist and sleep physician, interrogates the evolutionary, neurological, and psychological underpinnings of the seven greatest transgressions in Dante’s “Inferno”: wrath, lust, pride, greed, envy, sloth, and gluttony. He concludes that these so-called sins are inextricably interwoven with the experience of being a person, and that to understand them is “to gain insights into why we do what we do: the biology of being human.”

In “Seven Deadly Sins,” Leschziner, a neurologist and sleep physician, interrogates the evolutionary, neurological, and psychological underpinnings of the seven greatest transgressions in Dante’s “Inferno”: wrath, lust, pride, greed, envy, sloth, and gluttony. He concludes that these so-called sins are inextricably interwoven with the experience of being a person, and that to understand them is “to gain insights into why we do what we do: the biology of being human.”

Leschziner had several personal reasons for wanting to understand humanity’s darkest side. His family was defined by the trauma of his grandfather’s narrow escape from the Holocaust, a “supreme expression of human sin.” Leschziner’s curiosity about sin was also sparked by his 25 years as a doctor in London hospitals, where he’s seen the best and worst of humankind on display. In writing this book, he sought to push himself beyond merely observing and treating his patients’ issues and instead “to see beneath the surface, to delve into the depths.”

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Nobel Prize lecture: Geoffrey Hinton

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

World Order in a Time of Monsters

Minouche Shafik at Project Syndicate:

It is a multipolar world, with China, Russia, India, Turkey, Brazil, South Africa, and the Gulf states challenging the old order, alongside other emerging powers demanding a greater voice in shaping the rules of the international system. Meanwhile, belief in “universal values” and the idea of an “international community” has waned, as many point to the hypocrisy of rich countries hoarding vaccines during the COVID-19 pandemic and the response to the Ukraine war compared to the failures to act in response to humanitarian crises in Gaza, Sudan, and many other places.

It is a multipolar world, with China, Russia, India, Turkey, Brazil, South Africa, and the Gulf states challenging the old order, alongside other emerging powers demanding a greater voice in shaping the rules of the international system. Meanwhile, belief in “universal values” and the idea of an “international community” has waned, as many point to the hypocrisy of rich countries hoarding vaccines during the COVID-19 pandemic and the response to the Ukraine war compared to the failures to act in response to humanitarian crises in Gaza, Sudan, and many other places.

Adding to these pressures, US President Donald Trump has threatened to withdraw the security guarantees that have been crucial for Europe and Japan, quit many international organizations, and impose trade tariffs on friends and foes alike. When the guarantor of the system walks away from it, what comes next?

We may be heading to a zero-order world in which rules are replaced by power – a very difficult environment for smaller countries. Or it may be a world of large regional blocs, with the United States dominating its hemisphere, China prevailing over East Asia, and Russia reasserting control over the countries of the former Soviet Union. Ideally, we can find our way to a new rules-based order that more accurately reflects our multipolar world.

To get there, we need to better understand why the old order failed.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

W. G. Sebald | 92Y Readings

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.