Henry Farrell over at his substack, Programmable Mutter:

When Ezra Klein and Chris Hayes talked recently about Chris’s new book, The Siren’s Call: How Attention Became the World’s Most Endangered Resource, my friend John Sides took polite exception. His criticism doesn’t seem to be available online (it was in the newsletter for Good Authority) but his broad claim was that we should not pay too much attention to attention. Even if Trump and other Republicans are good at getting eyeballs, they may not win enough votes, and might even alienate people. Attracting attention may end up being a bad idea.

Good Authority is a political science publication* and John was making a case for the established wisdoms of political science. It was a good case, and one which, I am pretty sure that Chris would largely agree with (he says some pretty similar things in the book). But in the interests of good argument, I’d like to keep the dialectic going, counter-claiming that standard political science could greatly benefit from engaging with the ideas that Chris and Ezra batted around in their conversation, and that are discussed in greater depth in Chris’s book. Both podcast and book highlight problems that political scientists are bad at understanding. When political scientists think about attention, they usually rely on survey analysis and similar static means of capturing what citizens say about their attitudes. They do not, with occasional exceptions think much about the flows involved in therelationship between attention, technology and bandwidth.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

E

E

Some of the microbes that rose from the ocean fell on land instead of water. Lying on the bare continents, they no longer had sea water to shield them from direct sunlight. Many likely died as the ultraviolet radiation ravaged their genes and proteins. Meanwhile, the atmosphere was sucking out the water from their interiors, causing their molecules to stick together and collapse into toxic shapes.

Some of the microbes that rose from the ocean fell on land instead of water. Lying on the bare continents, they no longer had sea water to shield them from direct sunlight. Many likely died as the ultraviolet radiation ravaged their genes and proteins. Meanwhile, the atmosphere was sucking out the water from their interiors, causing their molecules to stick together and collapse into toxic shapes.

In his introduction, Clark poses a more immediate question: “Shouldn’t we judge political art by its effects, not its beauty or truth?” Leaving aside the second clause, we find two questionable assertions implicit in the first: namely, that art can be political and that it can have an effect. In this context, he imagines the reader wondering why his book “makes room for Matisse and Jackson Pollock,” two artists who “reached the conclusion, in practice, that opinions had to be what art annihilated if it was to survive”. Their stance is one that Clark accepts: “The blankness was essential. It was reality as they lived it.”

In his introduction, Clark poses a more immediate question: “Shouldn’t we judge political art by its effects, not its beauty or truth?” Leaving aside the second clause, we find two questionable assertions implicit in the first: namely, that art can be political and that it can have an effect. In this context, he imagines the reader wondering why his book “makes room for Matisse and Jackson Pollock,” two artists who “reached the conclusion, in practice, that opinions had to be what art annihilated if it was to survive”. Their stance is one that Clark accepts: “The blankness was essential. It was reality as they lived it.”

For those hoping to cure death, and they are legion, a 2016 experiment at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in San Diego has become liminal — the moment that changed everything. The experiment involved mice born to live fast and die young, bred with a rodent version of progeria, a condition that causes premature aging. Left alone, the animals grow gray and frail and then die about seven months later, compared to a lifespan of about two years for typical lab mice.

For those hoping to cure death, and they are legion, a 2016 experiment at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in San Diego has become liminal — the moment that changed everything. The experiment involved mice born to live fast and die young, bred with a rodent version of progeria, a condition that causes premature aging. Left alone, the animals grow gray and frail and then die about seven months later, compared to a lifespan of about two years for typical lab mice. The Great Gatsby

The Great Gatsby It’s no secret that modern English is saturated with French. Insults and derogatory terms owe much to the French example – bastard, brute, coward, rascal, idiot. French oozes from the language of food and drink: chowder echoes the old French chaudière, meaning a cooking pot, while crayfish started out as escrevise before the English chopped off its initial vowel (something they also did with scarf, stew, slice and a host of others) and decided that the last syllable sounding like ‘fish’ was just too good to pass up. From arson to evidence, jury to slander, French runs through the language of the English law (and the ‘Oyez! Oyez! Oyez!’ of the

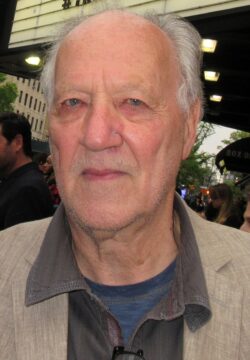

It’s no secret that modern English is saturated with French. Insults and derogatory terms owe much to the French example – bastard, brute, coward, rascal, idiot. French oozes from the language of food and drink: chowder echoes the old French chaudière, meaning a cooking pot, while crayfish started out as escrevise before the English chopped off its initial vowel (something they also did with scarf, stew, slice and a host of others) and decided that the last syllable sounding like ‘fish’ was just too good to pass up. From arson to evidence, jury to slander, French runs through the language of the English law (and the ‘Oyez! Oyez! Oyez!’ of the  I avoid contact with fans. Occasionally, I watch trash TV because I think the poet shouldn’t avert his eyes. I want to know what others aspire to. I’m a good but limited cook. My steaks are excellent, but they’ll never touch what you can get on any street corner in Argentina. Tree huggers are suspicious to me. Yoga classes for five-year-olds—which in California are a thing—are suspicious to me. I don’t use social media. If you see my profile anywhere there, you can be sure it’s a fake. I don’t use a smartphone. I never quite trust the media, so I get a truer picture of the political situation by going to multiple sources—the Western media, Al Jazeera, Russian TV, and occasionally by downloading the whole of a politician’s speech. I trust the Oxford English Dictionary, which is one of mankind’s greatest cultural achievements. I mean the one in twenty massive volumes with six hundred thousand entries and more than three million quotations culled from all over the English-speaking world and over a thousand years. I reckon thousands of researchers and amateur helpers spent 150 years combing through everything recorded. For me, it is the book of books, the one I would take to a desert island. It is inexhaustible, a miracle. The first time I visited Oliver Sacks on Wards Island north of Manhattan, I had mislaid the house number but knew the name of the little street. It was evening, winter-time; the slightly sloping street was icy. I parked and tiptoed along the icy pavement looking into every lit-up home. None of the windows had curtains. Through one window I saw a man sprawled on a sofa with one of the hefty volumes of the OED propped on his chest. I knew that had to be him, and so it was. Our first subject was the dictionary; for him as well, it was the book of books.

I avoid contact with fans. Occasionally, I watch trash TV because I think the poet shouldn’t avert his eyes. I want to know what others aspire to. I’m a good but limited cook. My steaks are excellent, but they’ll never touch what you can get on any street corner in Argentina. Tree huggers are suspicious to me. Yoga classes for five-year-olds—which in California are a thing—are suspicious to me. I don’t use social media. If you see my profile anywhere there, you can be sure it’s a fake. I don’t use a smartphone. I never quite trust the media, so I get a truer picture of the political situation by going to multiple sources—the Western media, Al Jazeera, Russian TV, and occasionally by downloading the whole of a politician’s speech. I trust the Oxford English Dictionary, which is one of mankind’s greatest cultural achievements. I mean the one in twenty massive volumes with six hundred thousand entries and more than three million quotations culled from all over the English-speaking world and over a thousand years. I reckon thousands of researchers and amateur helpers spent 150 years combing through everything recorded. For me, it is the book of books, the one I would take to a desert island. It is inexhaustible, a miracle. The first time I visited Oliver Sacks on Wards Island north of Manhattan, I had mislaid the house number but knew the name of the little street. It was evening, winter-time; the slightly sloping street was icy. I parked and tiptoed along the icy pavement looking into every lit-up home. None of the windows had curtains. Through one window I saw a man sprawled on a sofa with one of the hefty volumes of the OED propped on his chest. I knew that had to be him, and so it was. Our first subject was the dictionary; for him as well, it was the book of books.