Audrey Curry in Science:

On the wall of his living room in Lier, Belgium, Werner van Beethoven keeps a family tree. Thirteen generations unfurl along its branches, including one that shows his best known relative, born in 1770: Ludwig van Beethoven, who forever redefined Western music with compositions such as the Fifth Symphony, Für Elise, and others. Yet that sprig held a hereditary, and potentially scandalous, secret.

On the wall of his living room in Lier, Belgium, Werner van Beethoven keeps a family tree. Thirteen generations unfurl along its branches, including one that shows his best known relative, born in 1770: Ludwig van Beethoven, who forever redefined Western music with compositions such as the Fifth Symphony, Für Elise, and others. Yet that sprig held a hereditary, and potentially scandalous, secret.

That Beethoven, Werner learned to his dismay in 2023, is biologically unrelated to Werner and his contemporary kin. This uncomfortable fact was brought to light by Maarten Larmuseau, a geneticist at KU Leuven who specializes in answering a question relatively few others have explored: How often do women have children with men they’re not partnered with?

In most societies, kinship is at least partly socially constructed, and for example can include adoption and stepfamilies. Yet questions about biological paternity have roiled families and fueled cultural anxieties for eons. Male authors have written about hidden paternity for millennia, including in Greek dramas and The Canterbury Tales; William Shakespeare and Molière wrote plays about it. Knowing a child’s biological father is also important for forensically identifying cadavers, recording accurate medical histories, and charting the manifold ways in which people structure families around the world.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

In mid-March 2024, Daniel Kahneman flew from New York to Paris with his partner, Barbara Tversky, to unite with his daughter and her family. They spent days walking around the city, going to museums and the ballet, and savoring soufflés and chocolate mousse. Around March 22, Kahneman, who had turned 90 that month, also started emailing a personal message to several dozen of the people he was closest to. On March 26, Kahneman left his family and flew to Switzerland. His email explained why:

In mid-March 2024, Daniel Kahneman flew from New York to Paris with his partner, Barbara Tversky, to unite with his daughter and her family. They spent days walking around the city, going to museums and the ballet, and savoring soufflés and chocolate mousse. Around March 22, Kahneman, who had turned 90 that month, also started emailing a personal message to several dozen of the people he was closest to. On March 26, Kahneman left his family and flew to Switzerland. His email explained why: My wife Alma Gottlieb is an anthropologist, and for years we had lived in small villages in West Africa, among the Beng people of Côte d’Ivoire. In 1993, during our third extended stay, news of my father’s death back in the U.S. arrived in the village, too late for us to return for his funeral. Stunned, I couldn’t decide what to do, how to mourn, until village elders offered to give my American father the ceremonies of a traditional Beng funeral. After days of elaborate ritual, the village’s religious leader, Kokora Kouassi, confided to us that my father now visited him in his dreams—from Wurugbé, the Beng afterlife—with messages of farewell and comfort. The Beng believe the dead exist in an invisible social world beside the living, and Kouassi’s dreams were meant to assure me that my father wasn’t far away at all. Instead, he hovered invisibly beside me.

My wife Alma Gottlieb is an anthropologist, and for years we had lived in small villages in West Africa, among the Beng people of Côte d’Ivoire. In 1993, during our third extended stay, news of my father’s death back in the U.S. arrived in the village, too late for us to return for his funeral. Stunned, I couldn’t decide what to do, how to mourn, until village elders offered to give my American father the ceremonies of a traditional Beng funeral. After days of elaborate ritual, the village’s religious leader, Kokora Kouassi, confided to us that my father now visited him in his dreams—from Wurugbé, the Beng afterlife—with messages of farewell and comfort. The Beng believe the dead exist in an invisible social world beside the living, and Kouassi’s dreams were meant to assure me that my father wasn’t far away at all. Instead, he hovered invisibly beside me. Can you pass me the whatchamacallit? It’s right over there next to the thingamajig.

Can you pass me the whatchamacallit? It’s right over there next to the thingamajig. T

T In January,

In January, Nobel Laureate and a psychologist, best known for his work on psychology of judgment and decision-making as well as behavioural economics,

Nobel Laureate and a psychologist, best known for his work on psychology of judgment and decision-making as well as behavioural economics,  Covid was a privatized pandemic. It is this technocratic, privatized model that is its lasting legacy and that will define our approach to the next pandemic. It solves some problems, but on balance it’s a recipe for disaster. There are some public goods that should never be sold. Dr. Gounder checked off the basic mechanisms by which public health experts confront a pandemic: They create systems to understand and track its cause and spread; they identify the people most at risk; they deploy scalable mechanisms of protection, like air and water sanitation; they distribute necessary tools, such as vaccines and protective gear; they gather and communicate accurate information; and they try to balance individual freedoms and mass restrictions.

Covid was a privatized pandemic. It is this technocratic, privatized model that is its lasting legacy and that will define our approach to the next pandemic. It solves some problems, but on balance it’s a recipe for disaster. There are some public goods that should never be sold. Dr. Gounder checked off the basic mechanisms by which public health experts confront a pandemic: They create systems to understand and track its cause and spread; they identify the people most at risk; they deploy scalable mechanisms of protection, like air and water sanitation; they distribute necessary tools, such as vaccines and protective gear; they gather and communicate accurate information; and they try to balance individual freedoms and mass restrictions.

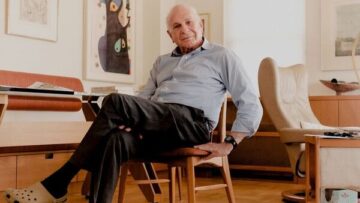

In the introduction to his latest book, How to Feed the World, Vaclav Smil writes that “numbers are the antidote to wishful thinking.” That one line captures why I’ve been such a devoted reader of this curmudgeonly Canada-based Czech academic for so many years. Across his decades of research and writing, Vaclav has tackled some of the biggest questions in energy, agriculture, and public health—not by making grand predictions, but by breaking down complex problems into measurable data.

In the introduction to his latest book, How to Feed the World, Vaclav Smil writes that “numbers are the antidote to wishful thinking.” That one line captures why I’ve been such a devoted reader of this curmudgeonly Canada-based Czech academic for so many years. Across his decades of research and writing, Vaclav has tackled some of the biggest questions in energy, agriculture, and public health—not by making grand predictions, but by breaking down complex problems into measurable data. ELAINE MAY DIDN’T SET OUT to become a director. What she really wanted to do was write. Her first film, A New Leaf, came about partly because it was 1968 and Paramount knew it would look good to hire a woman director. And partly because May wouldn’t sell her script without being guaranteed director approval—the only way to ensure her work didn’t get turned into something else entirely. The studio said no but told her she could direct the film herself; they also wouldn’t let her cast the female lead, but the part was hers if she wanted it. As May tells it, she had been offered $200,000 for the script alone, but as writer-director-star, she received just a quarter of the original fee. “You can’t expect to get that much the first time you direct,” her manager explained. Charles Bluhdorn, the industrialist who owned Paramount, told May that he was going to make her the next Ida Lupino. On the first day of shooting, when the crew asked May where she wanted the camera, she couldn’t find it. “I began sort of on one foot,” May remembered, “and just continued that way.” It was a fitting start for a woman who had become famous for improvising.

ELAINE MAY DIDN’T SET OUT to become a director. What she really wanted to do was write. Her first film, A New Leaf, came about partly because it was 1968 and Paramount knew it would look good to hire a woman director. And partly because May wouldn’t sell her script without being guaranteed director approval—the only way to ensure her work didn’t get turned into something else entirely. The studio said no but told her she could direct the film herself; they also wouldn’t let her cast the female lead, but the part was hers if she wanted it. As May tells it, she had been offered $200,000 for the script alone, but as writer-director-star, she received just a quarter of the original fee. “You can’t expect to get that much the first time you direct,” her manager explained. Charles Bluhdorn, the industrialist who owned Paramount, told May that he was going to make her the next Ida Lupino. On the first day of shooting, when the crew asked May where she wanted the camera, she couldn’t find it. “I began sort of on one foot,” May remembered, “and just continued that way.” It was a fitting start for a woman who had become famous for improvising.