Eric Reinhart & Craig Spencer at the Boston Review:

On Saturday Francis Collins resigned from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) after directing it for over a decade. His departure, coming on the heels of the expected confirmation of Stanford’s Jay Bhattacharya as his replacement, represents more than the loss of an influential physician-scientist who once led the Human Genome Project and played a central role in the United States’ COVID-19 response. It marks the culmination of a decades-long missed opportunity: despite being the world’s largest funder of biomedical research, the NIH has not built a broad public constituency to protect it from partisan destruction.

On Saturday Francis Collins resigned from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) after directing it for over a decade. His departure, coming on the heels of the expected confirmation of Stanford’s Jay Bhattacharya as his replacement, represents more than the loss of an influential physician-scientist who once led the Human Genome Project and played a central role in the United States’ COVID-19 response. It marks the culmination of a decades-long missed opportunity: despite being the world’s largest funder of biomedical research, the NIH has not built a broad public constituency to protect it from partisan destruction.

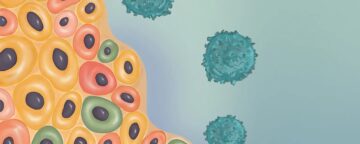

In his resignation letter, Collins notes that the institute “is the main piston of a biomedical discovery engine that is the envy of the globe. Yet it is not a household name. It should be.” He singles out two notable discoveries. “When you hear about patients surviving stage 4 cancer because of immunotherapy,” he writes, “that was based on NIH research over many decades.” And “when you hear about sickle-cell disease being cured because of CRISPR gene editing, that was built on many years of research supported by NIH.”

Collins is right, but he fails to mention the fundamental reason many Americans don’t credit the government for these achievements: they only ever learn of NIH’s work from intermediaries—deeply unpopular pharmaceutical or medical device companies—that take credit for NIH science while leveraging it to extract as much money as possible from desperate patients and families.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Whenever I read The Letters of Abelard and Héloïse I have in mind another, more contemporary couple, whose collaborative work I have come to think of as sacred, too. As soon as the performance artists Marina Abramović and Ulay met in the 1970s, they fell hard in love and began making performance art together. They called this work a “third energy,” their souls combined, a kind of artistic procreation (we don’t know what happened to Héloïse and Abelard’s child—only that she called him Astrolabe, after the astronomical instrument for reckoning with time and observing the stars. Astrolabe as the one instrument that could point up to the star-crossed lovers who made him and prove that their love had been real). The idea for “The Lovers” came to Abramović as a vision in a dream. They would walk from either end of the Great Wall of China to finally meet in the middle where they would marry, documenting the whole expedition on film—the kind of exaggeratedly cinematic, romantic scheme that is destined to go wrong. In the time it took to secure their visas—several years—the relationship had already begun to fall apart. Five years later, they set out at last to make “The Lovers.” After almost 90 days of walking, each covering over two thousand kilometres alone, they reunited on the wall, not to marry, but to break up. Watching the footage of “The Lovers,” I imagine they are actually Héloïse and Abelard, setting out on their private pilgrimages through life in the wake of their painful estrangement, then meeting in the middle again through the form of letters.

Whenever I read The Letters of Abelard and Héloïse I have in mind another, more contemporary couple, whose collaborative work I have come to think of as sacred, too. As soon as the performance artists Marina Abramović and Ulay met in the 1970s, they fell hard in love and began making performance art together. They called this work a “third energy,” their souls combined, a kind of artistic procreation (we don’t know what happened to Héloïse and Abelard’s child—only that she called him Astrolabe, after the astronomical instrument for reckoning with time and observing the stars. Astrolabe as the one instrument that could point up to the star-crossed lovers who made him and prove that their love had been real). The idea for “The Lovers” came to Abramović as a vision in a dream. They would walk from either end of the Great Wall of China to finally meet in the middle where they would marry, documenting the whole expedition on film—the kind of exaggeratedly cinematic, romantic scheme that is destined to go wrong. In the time it took to secure their visas—several years—the relationship had already begun to fall apart. Five years later, they set out at last to make “The Lovers.” After almost 90 days of walking, each covering over two thousand kilometres alone, they reunited on the wall, not to marry, but to break up. Watching the footage of “The Lovers,” I imagine they are actually Héloïse and Abelard, setting out on their private pilgrimages through life in the wake of their painful estrangement, then meeting in the middle again through the form of letters. To understand Trump’s political order, then, we need to familiarize ourselves with the

To understand Trump’s political order, then, we need to familiarize ourselves with the M

M D

D Building a film around a temperamental genius is never as simple as placing a star at its center. Murphy and Chalamet both do their parts: they create, they scowl, they have affairs. They are misunderstood. But their perceived genius is less about their particular actions than it is about the reactions of secondary characters. This is apparent throughout A Complete Unknown. In her review of the film, Vulture’s Alison Willmore highlights the cast around Chalamet: “Its best sequences aren’t about Dylan so much as they are about what it was like to be in his orbit when it felt like he could remake the universe.” The film succeeds because it captures how Dylan’s peers saw him—what made them want to be near him, what made them want to support his career.

Building a film around a temperamental genius is never as simple as placing a star at its center. Murphy and Chalamet both do their parts: they create, they scowl, they have affairs. They are misunderstood. But their perceived genius is less about their particular actions than it is about the reactions of secondary characters. This is apparent throughout A Complete Unknown. In her review of the film, Vulture’s Alison Willmore highlights the cast around Chalamet: “Its best sequences aren’t about Dylan so much as they are about what it was like to be in his orbit when it felt like he could remake the universe.” The film succeeds because it captures how Dylan’s peers saw him—what made them want to be near him, what made them want to support his career. In Kinsky’s latest novel,

In Kinsky’s latest novel,  I can’t recall the first time I saw “The Misfits,” John Huston’s 1961 cinematic masterpiece about a quartet of mutually disenfranchised wanderers, but I’m certain it was after I’d become a divorcée. I know it wouldn’t have stuck with me so permanently otherwise. Set in Reno, Nev., a city once as famous for its hassle-free divorces as its casinos, the film is a timeless meditation on what it means to lose.

I can’t recall the first time I saw “The Misfits,” John Huston’s 1961 cinematic masterpiece about a quartet of mutually disenfranchised wanderers, but I’m certain it was after I’d become a divorcée. I know it wouldn’t have stuck with me so permanently otherwise. Set in Reno, Nev., a city once as famous for its hassle-free divorces as its casinos, the film is a timeless meditation on what it means to lose. Working in the field of genetics is a bizarre experience. No one seems to be interested in the most interesting applications of their research.

Working in the field of genetics is a bizarre experience. No one seems to be interested in the most interesting applications of their research. The 20th century had a bunch of rising powers that all reached their peaks in terms not just of relative military might and economic strength, but of technological and cultural innovation. These included the United States, Japan, Germany, and Russia. So far, the 21st century is a little different, because only one major civilization is

The 20th century had a bunch of rising powers that all reached their peaks in terms not just of relative military might and economic strength, but of technological and cultural innovation. These included the United States, Japan, Germany, and Russia. So far, the 21st century is a little different, because only one major civilization is  Genetically engineered woolly mice could one day help populate the Arctic with hairy, genetically modified elephants and help stop the planet warming.

Genetically engineered woolly mice could one day help populate the Arctic with hairy, genetically modified elephants and help stop the planet warming. I

I A

A He began studying

He began studying