Martha Bayles in The Hedgehog Review:

In March 2019, heavy rains in California led to a brilliant carpet of orange poppies in Walker Canyon, part of a 500,000-acre habitat reserve in the Temescal Mountains southeast of Los Angeles. Run by a state conservation agency, the reserve was mainly a local attraction until a twenty-four-year-old Instagram and YouTube influencer with tens of thousands of followers posted two selfies of herself amid the poppies. The result, as technology critic Nicholas Carr explains in his book Superbloom (named after the viral hashtag #superbloom), brought a Woodstock-size influx of selfie-seekers who “clogged roads and highways,” “trampled the delicate flowers,” and in general “offered a portrait in miniature of our frenzied, farcical, information-saturated time.”

In March 2019, heavy rains in California led to a brilliant carpet of orange poppies in Walker Canyon, part of a 500,000-acre habitat reserve in the Temescal Mountains southeast of Los Angeles. Run by a state conservation agency, the reserve was mainly a local attraction until a twenty-four-year-old Instagram and YouTube influencer with tens of thousands of followers posted two selfies of herself amid the poppies. The result, as technology critic Nicholas Carr explains in his book Superbloom (named after the viral hashtag #superbloom), brought a Woodstock-size influx of selfie-seekers who “clogged roads and highways,” “trampled the delicate flowers,” and in general “offered a portrait in miniature of our frenzied, farcical, information-saturated time.”

Today, Walker Canyon is closed until further notice. But the frenzied farce continues, as Donald Trump’s electoral victory sets the Big Tech companies against one another in a new, more politically visible way. If you’re wondering how we arrived at this pass, Carr is your man. An eloquent, levelheaded writer, he has been sticking pins into the hot-air optimism of Big Tech since 2001, when, as editor of the Harvard Business Review, he published several politely skeptical articles on the uses of what was then the new “information technology.” Less politely, and with sharper pins, Superbloom appraises the past and present of that technology and issues a warning about its future.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

‘I assume that the reader is familiar with the idea of extra-sensory perception … telepathy, clairvoyance, precognition and psycho-kinesis. These disturbing phenomena seem to deny all our usual scientific ideas … Unfortunately the statistical evidence, at least for telepathy, is overwhelming … Once one has accepted them it does not seem a very big step to believe in ghosts and bogies.’

‘I assume that the reader is familiar with the idea of extra-sensory perception … telepathy, clairvoyance, precognition and psycho-kinesis. These disturbing phenomena seem to deny all our usual scientific ideas … Unfortunately the statistical evidence, at least for telepathy, is overwhelming … Once one has accepted them it does not seem a very big step to believe in ghosts and bogies.’ T

T C

C On a rainy day in July 2024, Tim Bliss and Terje Lømo are in the best of moods, chuckling and joking over brunch, occasionally pounding the table to make a point. They’re at Lømo’s house near Oslo, Norway, where they’ve met to write about the

On a rainy day in July 2024, Tim Bliss and Terje Lømo are in the best of moods, chuckling and joking over brunch, occasionally pounding the table to make a point. They’re at Lømo’s house near Oslo, Norway, where they’ve met to write about the  Since Sir Francis Galton coined the phrase “nature versus nurture” 150 years ago, the debate about what makes us who we are has dominated the human sciences.

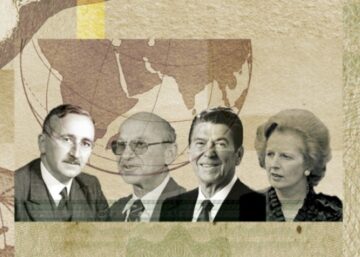

Since Sir Francis Galton coined the phrase “nature versus nurture” 150 years ago, the debate about what makes us who we are has dominated the human sciences. If critique could kill, neoliberalism would long be dead. So far, however, neither decades of intellectual opposition from the left and right nor the past decade of populist politics has done more than erode some measure of neoliberalism’s ideological preeminence. Talk from the right of “pro-family” policies, such as tax breaks and subsidies for having children, or moves by the Biden administration to secure domestic manufacturing of critical high-technology goods may hearten neoliberalism’s foes (even as they further blur the ideological map of American politics). Neither, however, offers anything like a consensus to replace the vision that, since the crises of the 1970s, has, with whatever degree of discontent, guided our collective thought and action.

If critique could kill, neoliberalism would long be dead. So far, however, neither decades of intellectual opposition from the left and right nor the past decade of populist politics has done more than erode some measure of neoliberalism’s ideological preeminence. Talk from the right of “pro-family” policies, such as tax breaks and subsidies for having children, or moves by the Biden administration to secure domestic manufacturing of critical high-technology goods may hearten neoliberalism’s foes (even as they further blur the ideological map of American politics). Neither, however, offers anything like a consensus to replace the vision that, since the crises of the 1970s, has, with whatever degree of discontent, guided our collective thought and action. An Australian man in his forties has become the first person in the world to leave hospital with an artificial heart made of titanium. The device is used as a stopgap for people with heart failure who are waiting for a donor heart, and previous recipients of this type of artificial heart had remained in US hospitals while it was in place.

An Australian man in his forties has become the first person in the world to leave hospital with an artificial heart made of titanium. The device is used as a stopgap for people with heart failure who are waiting for a donor heart, and previous recipients of this type of artificial heart had remained in US hospitals while it was in place. [SSW: The next quote is Pinker’s rebuttal of a common response to Judith Rich Harris’s claim that parents have little impact on their kids.] “‘So you’re saying it doesn’t matter how I treat my children?’ What a question! Yes, of course it matters… First, parents wield enormous power over their children, and their actions can make a big difference to their happiness… It is not OK for parents to beat, humiliate, deprive, or neglect their children, because those are awful things for a big strong person to do to a small helpless one… Second, a parent and a child have a human relationship. No one ever asks, ‘So you’re saying it doesn’t matter how I treat my husband or wife?’ even though no one but a newlywed believes that one can change the personality of one’s spouse. Husbands and wives are nice to each other (or should be) not to pound the other’s personality into a desired shape but to build a deep and satisfying relationship.”

[SSW: The next quote is Pinker’s rebuttal of a common response to Judith Rich Harris’s claim that parents have little impact on their kids.] “‘So you’re saying it doesn’t matter how I treat my children?’ What a question! Yes, of course it matters… First, parents wield enormous power over their children, and their actions can make a big difference to their happiness… It is not OK for parents to beat, humiliate, deprive, or neglect their children, because those are awful things for a big strong person to do to a small helpless one… Second, a parent and a child have a human relationship. No one ever asks, ‘So you’re saying it doesn’t matter how I treat my husband or wife?’ even though no one but a newlywed believes that one can change the personality of one’s spouse. Husbands and wives are nice to each other (or should be) not to pound the other’s personality into a desired shape but to build a deep and satisfying relationship.” The French scholar Pierre-Simon Laplace crisply articulated his expectation that the universe was fully knowable in 1814, asserting that a sufficiently clever “demon” could predict the entire future given a complete knowledge of the present. His thought experiment marked the height of optimism about what physicists might forecast. Since then, reality has repeatedly humbled their ambitions to understand it.

The French scholar Pierre-Simon Laplace crisply articulated his expectation that the universe was fully knowable in 1814, asserting that a sufficiently clever “demon” could predict the entire future given a complete knowledge of the present. His thought experiment marked the height of optimism about what physicists might forecast. Since then, reality has repeatedly humbled their ambitions to understand it. We can give ourselves far, far more than Donald Trump can ever take away, but it will—it will take extraordinary efforts. It won’t be business as usual. We will have to do things we haven’t imagined before, at speeds we didn’t think possible. […] I know, I know that these are dark days, dark days brought on by a country we can no longer trust. We are getting over the shock, but let us never forget the lessons: we have to look after ourselves and we have to look out for each other. We need to pull together in the tough days ahead.

We can give ourselves far, far more than Donald Trump can ever take away, but it will—it will take extraordinary efforts. It won’t be business as usual. We will have to do things we haven’t imagined before, at speeds we didn’t think possible. […] I know, I know that these are dark days, dark days brought on by a country we can no longer trust. We are getting over the shock, but let us never forget the lessons: we have to look after ourselves and we have to look out for each other. We need to pull together in the tough days ahead. T

T What do a mobile shooting game, a nuclear power plant, and a local Chinese government office have in common? In the past two months, they have all tried incorporating DeepSeek’s R1

What do a mobile shooting game, a nuclear power plant, and a local Chinese government office have in common? In the past two months, they have all tried incorporating DeepSeek’s R1  Given the chance to become a movie director in Hollywood or a professor of philosophy at Harvard, I imagine very few of us would choose the academic life. The money and fame of being a movie director are far more tantalizing than teaching Plato, Kant, or Simone de Beauvoir. Terrence Malick chose to become a movie director instead of a philosophy professor, but not for the reasons you might think. It was not money and fame that convinced him, but the inability of philosophy courses to help “him understand himself and his place in the order of the cosmos” as Martin Woessner explained in a

Given the chance to become a movie director in Hollywood or a professor of philosophy at Harvard, I imagine very few of us would choose the academic life. The money and fame of being a movie director are far more tantalizing than teaching Plato, Kant, or Simone de Beauvoir. Terrence Malick chose to become a movie director instead of a philosophy professor, but not for the reasons you might think. It was not money and fame that convinced him, but the inability of philosophy courses to help “him understand himself and his place in the order of the cosmos” as Martin Woessner explained in a