Coquí

from Book Links

Poetry Magazine

Siddhartha Mukherjee in The New York Times:

On my way to a meeting on cancer and personalized medicine a few weeks ago, I found myself thinking, improbably, of the Saul Steinberg New Yorker cover illustration “View From Ninth Avenue.” Steinberg’s drawing (yes, you’ve seen it — in undergraduate dorm rooms, in subway ads) depicts a mental map of the world viewed through the eyes of a typical New Yorker. We’re somewhere on Ninth Avenue, looking out toward the water. Tenth Avenue looms large, thrumming with pedestrians and traffic. The Hudson is a band of gray-blue. But the rest of the world is gone — irrelevant, inconsequential, specks of sesame falling off a bagel. Kansas City, Chicago, Las Vegas and Los Angeles are blips on the horizon. There’s a strip of water denoting the Pacific Ocean, and faraway blobs of rising land: Japan, China, Russia. The whole thing is a wry joke on self-obsession and navel gazing: A New Yorker’s world begins and ends in New York.

On my way to a meeting on cancer and personalized medicine a few weeks ago, I found myself thinking, improbably, of the Saul Steinberg New Yorker cover illustration “View From Ninth Avenue.” Steinberg’s drawing (yes, you’ve seen it — in undergraduate dorm rooms, in subway ads) depicts a mental map of the world viewed through the eyes of a typical New Yorker. We’re somewhere on Ninth Avenue, looking out toward the water. Tenth Avenue looms large, thrumming with pedestrians and traffic. The Hudson is a band of gray-blue. But the rest of the world is gone — irrelevant, inconsequential, specks of sesame falling off a bagel. Kansas City, Chicago, Las Vegas and Los Angeles are blips on the horizon. There’s a strip of water denoting the Pacific Ocean, and faraway blobs of rising land: Japan, China, Russia. The whole thing is a wry joke on self-obsession and navel gazing: A New Yorker’s world begins and ends in New York.

In the mid-2000s, it felt to me, at times, as if cancer medicine were viewing the world from its own Ninth Avenue. Our collective vision was dominated by genomics — by the newfound capacity to sequence the genomes of cells (a “genome” refers to the complete set of genetic material present in an organism or a cell). Cancer, of course, is typically a disease caused by mutant genes that drive abnormal cellular growth (other features of cellular physiology, like the cell’s metabolism and survival, are also affected). By identifying the mutant genes in cancer cells, the logic ran, we would devise new ways of killing the cells. And because the exact set of mutations was unique to an individual patient — one woman’s breast cancer might have mutations in 12 genes, while another breast cancer might have mutations in a different set of 16 — we would “personalize” cancer medicine to that patient, thereby vastly increasing the effectiveness of therapy.

This kind of thinking had an exhilarating track record. In the 2000s, a medicine called Herceptin was shown to be effective for women with breast cancer, but only if the cancer cells carried a genetic aberration in a gene called HER-2. Another drug, Gleevec, worked only if the tumor cells had a mutant gene called BCR-ABL, or a mutation in a gene called c-kit. In many of our genome-obsessed minds, the problem of cancer had become reduced to a rather simple, scalable algorithm: find the mutations in a patient, and match those mutations with a medicine. All the other variables — the cellular environment within which the cancer cell was inescapably lodged, the metabolic and hormonal milieu that surrounded the cancer or, for that matter, the human body that was wrapped around it — might as well have been irrelevant blobs receding in the distance: Japan, China, Russia.

Christine Smallwood in Bookforum:

By the time Couples came out, John Updike had already published four novels, three story collections, two poetry collections, and a volume of assorted prose. He had been called, by the New York Times Book Review, “the most significant young novelist in America,” and had been sent by the State Department on a tour of the Communist bloc. And yet there was a growing sense that he had not made a major statement on the issues of the day. He could describe a barn well enough, but to what end? The man whose name will be forever asterisked with the insult David Foster Wallace made famous—“just a penis with a thesaurus”—was thought to be clever but a little small, too decorative, and overly fond of childhood reminiscence. Norman Podhoretz complained that Updike “has very little to say.” John Aldridge put him in “the second or just possibly the third rank of serious American novelists.” Elizabeth Hardwick admired Rabbit, Run, but thought there was “something insignificant, or understated, or too dimly felt in the heart of Rabbit himself.” As for his sexual frankness, Updike, like his contemporaries, had “not decided or discovered in what way this frankness will change the work itself. It cannot be merely interlarded like suet in the roast.”

By the time Couples came out, John Updike had already published four novels, three story collections, two poetry collections, and a volume of assorted prose. He had been called, by the New York Times Book Review, “the most significant young novelist in America,” and had been sent by the State Department on a tour of the Communist bloc. And yet there was a growing sense that he had not made a major statement on the issues of the day. He could describe a barn well enough, but to what end? The man whose name will be forever asterisked with the insult David Foster Wallace made famous—“just a penis with a thesaurus”—was thought to be clever but a little small, too decorative, and overly fond of childhood reminiscence. Norman Podhoretz complained that Updike “has very little to say.” John Aldridge put him in “the second or just possibly the third rank of serious American novelists.” Elizabeth Hardwick admired Rabbit, Run, but thought there was “something insignificant, or understated, or too dimly felt in the heart of Rabbit himself.” As for his sexual frankness, Updike, like his contemporaries, had “not decided or discovered in what way this frankness will change the work itself. It cannot be merely interlarded like suet in the roast.”

With Couples, Updike served up a whole plate of suet. (Do you understand the genius of Hardwick’s metaphor? Suet is the hard white fat on the loins of beef or mutton.) He worked out the plot in church, jotting down notes on the weekly program—maybe that’s why the book has the air of being so scandalized by itself.

More here.

Ed Yong in The Atlantic:

The Congo is one of the most biodiverse countries in the world. It was here that HIV bubbled into a pandemic, eventually detected half a world away, in California. It was here that monkeypox was first documented in people. The country has seen outbreaks of Marburg virus, Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever, chikungunya virus, yellow fever. These are all zoonotic diseases, which originate in animals and spill over into humans. Wherever people push into wildlife-rich habitats, the potential for such spillover is high. Sub-Saharan Africa’s population will more than double during the next three decades, and urban centers will extend farther into wilderness, bringing large groups of immunologically naive people into contact with the pathogens that skulk in animal reservoirs—Lassa fever from rats, monkeypox from primates and rodents, Ebola from God-knows-what in who-knows-where.

The Congo is one of the most biodiverse countries in the world. It was here that HIV bubbled into a pandemic, eventually detected half a world away, in California. It was here that monkeypox was first documented in people. The country has seen outbreaks of Marburg virus, Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever, chikungunya virus, yellow fever. These are all zoonotic diseases, which originate in animals and spill over into humans. Wherever people push into wildlife-rich habitats, the potential for such spillover is high. Sub-Saharan Africa’s population will more than double during the next three decades, and urban centers will extend farther into wilderness, bringing large groups of immunologically naive people into contact with the pathogens that skulk in animal reservoirs—Lassa fever from rats, monkeypox from primates and rodents, Ebola from God-knows-what in who-knows-where.

On average, in one corner of the world or another, a new infectious disease has emerged every year for the past 30 years: mers, Nipah, Hendra, and many more. Researchers estimate that birds and mammals harbor anywhere from 631,000 to 827,000 unknown viruses that could potentially leap into humans. Valiant efforts are under way to identify them all, and scan for them in places like poultry farms and bushmeat markets, where animals and people are most likely to encounter each other. Still, we likely won’t ever be able to predict which will spill over next; even long-known viruses like Zika, which was discovered in 1947, can suddenly develop into unforeseen epidemics.

More here.

Cass R. Sunstein in the New York Review of Books:

Liberal democracy has enjoyed much better days. Vladimir Putin has entrenched authoritarian rule and is firmly in charge of a resurgent Russia. In global influence, China may have surpassed the United States, and Chinese president Xi Jinping is now empowered to remain in office indefinitely. In light of recent turns toward authoritarianism in Turkey, Poland, Hungary, and the Philippines, there is widespread talk of a “democratic recession.” In the United States, President Donald Trump may not be sufficiently committed to constitutional principles of democratic government.

Liberal democracy has enjoyed much better days. Vladimir Putin has entrenched authoritarian rule and is firmly in charge of a resurgent Russia. In global influence, China may have surpassed the United States, and Chinese president Xi Jinping is now empowered to remain in office indefinitely. In light of recent turns toward authoritarianism in Turkey, Poland, Hungary, and the Philippines, there is widespread talk of a “democratic recession.” In the United States, President Donald Trump may not be sufficiently committed to constitutional principles of democratic government.

In such a time, we might be tempted to try to learn something from earlier turns toward authoritarianism, particularly the triumphant rise of the Nazis in Germany in the 1930s. The problem is that Nazism was so horrifying and so barbaric that for many people in nations where authoritarianism is now achieving a foothold, it is hard to see parallels between Hitler’s regime and their own governments. Many accounts of the Nazi period depict a barely imaginable series of events, a nation gone mad. That makes it easy to take comfort in the thought that it can’t happen again.

But some depictions of Hitler’s rise are more intimate and personal. They focus less on well-known leaders, significant events, state propaganda, murders, and war, and more on the details of individual lives. They help explain how people can not only participate in dreadful things but also stand by quietly and live fairly ordinary days in the midst of them. They offer lessons for people who now live with genuine horrors, and also for those to whom horrors may never come but who live in nations where democratic practices and norms are under severe pressure.

More here.

Robert B. Talisse in 3:AM Magazine:

It seems everyone these days laments the polarized condition of democratic politics. It is widely agreed that fake news is a central cause of the degradation of our political culture. That there is accord on this point is noteworthy. Perhaps the consensus on fake news offers a swath of common ground amidst all of the divisiveness? Maybe our shared condemnation of fake news provides a basis for a broader plan for rehabilitating democracy?

It seems everyone these days laments the polarized condition of democratic politics. It is widely agreed that fake news is a central cause of the degradation of our political culture. That there is accord on this point is noteworthy. Perhaps the consensus on fake news offers a swath of common ground amidst all of the divisiveness? Maybe our shared condemnation of fake news provides a basis for a broader plan for rehabilitating democracy?

Such optimism might be premature. The unanimity over fake news possibly owes more to the semantics of the word fake than to a convergence of political values. Note that to call something fake is, at the very least, to mark it as suspect; it is to say that it is posing as something it’s not. So, yes, everyone denounces fake news. We oppose that which professes to be news, but isn’t. But we do not thereby agree about which institutions and reports are authentic. Unless there is a shared view of what fake news is, the consensus about its dangers is likely merely verbal, thus providing no basis for a rehabilitation plan.

There is as yet no canonical definition of fake news. Still, there might be reason to hope. Perhaps we share a conception of fake news that is inchoate, waiting for an explicit definition. Given this possibility, we should attempt to devise a definition.

More here.

Brian Resnick in Vox:

The Stanford Prison Experiment, one of the most famous and compelling psychological studies of all time, told us a tantalizingly simple story about human nature.

The Stanford Prison Experiment, one of the most famous and compelling psychological studies of all time, told us a tantalizingly simple story about human nature.

The study took paid participants and assigned them to be “inmates” or “guards” in a mock prison at Stanford University. Soon after the experiment began, the “guards” began mistreating the “prisoners,” implying evil is brought out by circumstance. The authors, in their conclusions, suggested innocent people, thrown into a situation where they have power over others, will begin to abuse that power. And people who are put into a situation where they are powerless will be driven to submission, even madness.

The Stanford Prison Experiment has been included in many, many introductory psychology textbooks and is often cited uncritically. It’s the subject of movies, documentaries, books, television shows, and congressional testimony.

But its findings were wrong. Very wrong. And not just due to its questionable ethics or lack of concrete data — but because of deceit.

More here.

From Open Culture:

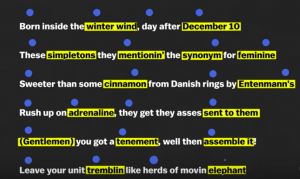

If high school English teachers can challenge skeptical students to cultivate an appreciation for Shakespeare and poetry with rap-based assignments, might the reverse also hold true?

If high school English teachers can challenge skeptical students to cultivate an appreciation for Shakespeare and poetry with rap-based assignments, might the reverse also hold true?

Many aficionados of high culture turn up their noses at rap, believing it to be a simple form, requiring more braggadocio than talent.

Estelle Caswell, rap fan and producer of Vox’s Earworm series, may get them to rethink that position with the above video, showcasing how great rappers assemble rhymes.

Caswell uses visual graphing to explain the progress from the A-A-B-B scheme of early rapper Kurtis Blow’s “The Breaks” (1980) to the complex and surprising holorimes of her personal favorite, MF DOOM.

To appreciate her visual breakdowns, you must understand that raps can be scored like traditional music.

More here. [Thanks to Sean Carroll.]

From BBC:

Eid al-Fitr is “the feast of the breaking of the fast” that begins when the moon rises on the final day of Ramadan. About 1.6 billion Muslims across the world marked the festival this year.

More here.

Robin Varghese in Foreign Affairs [free registration required to read]:

After nearly every economic downturn, voices appear suggesting that Marx was right to predict that the system would eventually destroy itself. Today, however, the problem is not a sudden crisis of capitalism but its normal workings, which in recent decades have revived pathologies that the developed world seemed to have left behind.

After nearly every economic downturn, voices appear suggesting that Marx was right to predict that the system would eventually destroy itself. Today, however, the problem is not a sudden crisis of capitalism but its normal workings, which in recent decades have revived pathologies that the developed world seemed to have left behind.

Since 1967, median household income in the United States, adjusted for inflation, has stagnated for the bottom 60 percent of the population, even as wealth and income for the richest Americans have soared. Changes in Europe, although less stark, point in the same direction. Corporate profits are at their highest levels since the 1960s, yet corporations are increasingly choosing to save those profits rather than invest them, further hurting productivity and wages. And recently, these changes have been accompanied by a hollowing out of democracy and its replacement with technocratic rule by globalized elites.

Mainstream theorists tend to see these developments as a puzzling departure from the promises of capitalism, but they would not have surprised Marx. He predicted that capitalism’s internal logic would over time lead to rising inequality, chronic unemployment and underemployment, stagnant wages, the dominance of large, powerful firms, and the creation of an entrenched elite whose power would act as a barrier to social progress. Eventually, the combined weight of these problems would spark a general crisis, ending in revolution.

Marx believed the revolution would come in the most advanced capitalist economies. Instead, it came in less developed ones, such as Russia and China, where communism ushered in authoritarian government and economic stagnation. During the middle of the twentieth century, meanwhile, the rich countries of Western Europe and the United States learned to manage, for a time, the instability and inequality that had characterized capitalism in Marx’s day. Together, these trends discredited Marx’s ideas in the eyes of many.

More here.

Ed Yong in The Atlantic:

Frank Jacobs, then at the University of California at Santa Cruz, had taken stem cells from humans and monkeys, and coaxed them into forming small balls of neurons. These “organoids” mirror the early stages of brain development. By studying them, Jacobs could look for genes that are switched on more strongly in the growing brains of humans than in those of monkeys. And when he presented his data to his colleagues at a lab meeting, one gene grabbed everyone’s attention.

Frank Jacobs, then at the University of California at Santa Cruz, had taken stem cells from humans and monkeys, and coaxed them into forming small balls of neurons. These “organoids” mirror the early stages of brain development. By studying them, Jacobs could look for genes that are switched on more strongly in the growing brains of humans than in those of monkeys. And when he presented his data to his colleagues at a lab meeting, one gene grabbed everyone’s attention.

“There was a gene called NOTCH2NL that was screaming in humans and off in [the monkeys],” says Sofie Salama, who co-directs the Santa Cruz team with David Haussler. “What the hell is NOTCH2NL? None of us had ever heard of it.”

The team ultimately learned that NOTCH2NL appears to be inactive in monkeys because it doesn’t exist in monkeys. It’s unique to humans, and it likely controls the number of neurons we make as embryos. It’s one of a growing list of human-only genes that could help explain why our brains are so much bigger than those of other apes.

More here.

From The Guardian:

An enigmatic sculpture of a king’s head dating back nearly 3,000 years has left researchers guessing at whose face it depicts.

An enigmatic sculpture of a king’s head dating back nearly 3,000 years has left researchers guessing at whose face it depicts.

The 5cm (two-inch) sculpture is an exceedingly rare example of figurative art from the region during the ninth century BC – a period associated with biblical kings. It is exquisitely preserved but for a bit of missing beard, and nothing quite like it has been found before.

While scholars are certain the stern-bearded figure wearing a golden crown represents royalty, they are less sure which king it symbolises, or which kingdom he may have ruled.

More here.

Matthew Boudway interviews Wim Wenders at Commonweal:

And then again this was, as filmmaking goes, not so different, at least in the impulse behind it, from some of my other films, because my documentaries don’t come out of a critical distance. Other filmmakers make films about something they want to expose or something they want to explore, or something that’s wrong with the world. My documentaries are all about things that I love and they show my affection, my desire to share this with as many people as possible, and that was definitely the case with Pope Francis. I loved this man and what he stood for, so anybody who expects a film that’s critical of the church or its policies is looking for the wrong movie. Already when I was a young film critic (I started as a film critic when I was a student and I earned money for my studies by writing criticism about movies) I refused to write about films I didn’t like. I thought it was not worth my time, or anybody’s time. I really only wrote about films I liked. And in a way that continued in my filmmaking career. I can’t even work with actors I don’t like. I don’t know what to do with them. I don’t know how to film them.

And then again this was, as filmmaking goes, not so different, at least in the impulse behind it, from some of my other films, because my documentaries don’t come out of a critical distance. Other filmmakers make films about something they want to expose or something they want to explore, or something that’s wrong with the world. My documentaries are all about things that I love and they show my affection, my desire to share this with as many people as possible, and that was definitely the case with Pope Francis. I loved this man and what he stood for, so anybody who expects a film that’s critical of the church or its policies is looking for the wrong movie. Already when I was a young film critic (I started as a film critic when I was a student and I earned money for my studies by writing criticism about movies) I refused to write about films I didn’t like. I thought it was not worth my time, or anybody’s time. I really only wrote about films I liked. And in a way that continued in my filmmaking career. I can’t even work with actors I don’t like. I don’t know what to do with them. I don’t know how to film them.

more here.

Matthew Engel at Literary Review:

Hatherley has a remarkable set of skills: he has the architectural, historical and political knowledge and the literary gifts to make him a worthy successor to the late, great and now rediscovered Ian Nairn – and occasionally some of the passion, too. Unfortunately, it all comes together here only in fits and starts. The main reason for that becomes clear at the end, in the acknowledgements, where he admits that the book is ‘essentially an anthology’. The majority of the chapters – portraits of individual cities – started as articles, published elsewhere, mostly in the Architects’ Journal.

Hatherley has a remarkable set of skills: he has the architectural, historical and political knowledge and the literary gifts to make him a worthy successor to the late, great and now rediscovered Ian Nairn – and occasionally some of the passion, too. Unfortunately, it all comes together here only in fits and starts. The main reason for that becomes clear at the end, in the acknowledgements, where he admits that the book is ‘essentially an anthology’. The majority of the chapters – portraits of individual cities – started as articles, published elsewhere, mostly in the Architects’ Journal.

There seems to me to be a helluva difference between writing for architects and appealing to moderately intelligent travellers, anxious to be told what they ought to be thinking but confident enough to disagree.

more here.

Patrick William Kelly at the LARB:

If human rights are to survive our fraught present and endure in the future, it is incumbent upon scholars to adopt a far more critical stance toward the study of human rights than they have so far been willing to do. Of course, academics have responded to the urgency of this crisis in a myriad of ways, and some had warned of the coming catastrophe from the politics of human rights. Despite the assault on human rights, some scholars cling to an uplifting and triumphalist story of the rise of human rights, one that leaves us both unable to understand the present and incapable of navigating the future. In this myth, humanity’s history is rendered as a slow but steady account of progress that will culminate in an Elysium of human rights. Far from helping us make sense of the challenges of our confusing present of human rights, these quixotic quests ransack the past in search of feel-good narratives of moral ascent and stirring stories of “hope” in the future — as if the misrepresentation of the past will magically bring about a brighter future in the name of human rights.

If human rights are to survive our fraught present and endure in the future, it is incumbent upon scholars to adopt a far more critical stance toward the study of human rights than they have so far been willing to do. Of course, academics have responded to the urgency of this crisis in a myriad of ways, and some had warned of the coming catastrophe from the politics of human rights. Despite the assault on human rights, some scholars cling to an uplifting and triumphalist story of the rise of human rights, one that leaves us both unable to understand the present and incapable of navigating the future. In this myth, humanity’s history is rendered as a slow but steady account of progress that will culminate in an Elysium of human rights. Far from helping us make sense of the challenges of our confusing present of human rights, these quixotic quests ransack the past in search of feel-good narratives of moral ascent and stirring stories of “hope” in the future — as if the misrepresentation of the past will magically bring about a brighter future in the name of human rights.

more here.

Kamila Shamsie in The Guardian:

Here is a novel that could so easily have been loud. It is set among large events: the fight for Indian independence and the second world war. It features characters from history who enter the lives of the novel’s fictional characters, often to dramatic effect – the poet Rabindranath Tagore, the singer Begum Akhtar, the dancer and critic Beryl de Zoete and the German painter and curator Walter Spies. It has at its heart a young boy whose mother leaves him to live in another country, and whose father responds to this crisis by also leaving the child for an extended period of time, and who is later imprisoned for his anti-British activism. There are many reasons to turn up the volume dial.

Here is a novel that could so easily have been loud. It is set among large events: the fight for Indian independence and the second world war. It features characters from history who enter the lives of the novel’s fictional characters, often to dramatic effect – the poet Rabindranath Tagore, the singer Begum Akhtar, the dancer and critic Beryl de Zoete and the German painter and curator Walter Spies. It has at its heart a young boy whose mother leaves him to live in another country, and whose father responds to this crisis by also leaving the child for an extended period of time, and who is later imprisoned for his anti-British activism. There are many reasons to turn up the volume dial.

But readers of Anuradha Roy, whose previous novel Sleeping on Jupiter was longlisted for the 2015 Man Booker prize, know that shoutiness or showiness is never her style. She is a writer of great subtlety and intelligence, who understands that emotional power comes from the steady accretion of detail. Amid all the great events and characters of history, she chooses as her narrator a horticulturalist known throughout by his nickname, Myshkin – “a man who chose neither pen nor sword but a trowel”. Myshkin is nine years old when his mother leaves him and his father in the fictitious Indian town of Muntazir, and embarks on a new life with Spies. Muntazir is 20 or so miles from the Himalayan foothills, and its name means, in Urdu, “one who waits impatiently”. After his mother’s departure, Myshkin’s life is spent anxiously waiting – for her letters to arrive, for her to return. In later years, he compares that waiting to “blood being drained away from our bodies until one day there was no more left”. The older Myshkin, a man in his 60s, narrates the story. He is the adult version of the child whose blood drained away, now living quietly, more at home among trees than people. In the course of this deliberately self-contained life, a bulky envelope arrives one day. It has something to do with his mother, he knows, and he cannot bring himself either to open it or to throw it away. Instead, his narration takes us back to his mother’s childhood, and then to his own childhood. He is a man seeking to understand why his mother, Gayatri, made the choice she did – and to this end he delves into the unusual freedom of her adolescence, compared with the rigidity and constraint of her married existence in 1930s India.

More here.

Erin Brodwin in Business Insider:

Earlier this week, reports linking the blockbuster gene-editing tool CRISPR to cancer in two studies sent investors scrambling to pull out of companies working on the technology, which is being studied for use in everything from food to medicine. The tool’s precise cut-and-paste approach to gene editing allows for a range of promising medical applications, from curing sickle cell anemia to preventing some forms of blindness. On Monday afternoon, headlines suggested that cells edited with the tool were more likely to become cancerous. Within hours of the reports being published, shares of Editas Medicine, CRISPR Therapeutics, Intellia Therapeutics, and Sangamo Therapeutics — all of which are trying to bring CRISPR to medicine — took a significant tumble. But scientists who study CRISPR and other methods of gene editing call the reports “overblown.” They say the link to cancer is tenuous at best and an incorrect interpretation of the results at worst. “This is absurd,” John Doench, the associate director of the genetic perturbation platform at MIT’s Broad Institute, told Business Insider. “There was a massive overreaction here.”

Earlier this week, reports linking the blockbuster gene-editing tool CRISPR to cancer in two studies sent investors scrambling to pull out of companies working on the technology, which is being studied for use in everything from food to medicine. The tool’s precise cut-and-paste approach to gene editing allows for a range of promising medical applications, from curing sickle cell anemia to preventing some forms of blindness. On Monday afternoon, headlines suggested that cells edited with the tool were more likely to become cancerous. Within hours of the reports being published, shares of Editas Medicine, CRISPR Therapeutics, Intellia Therapeutics, and Sangamo Therapeutics — all of which are trying to bring CRISPR to medicine — took a significant tumble. But scientists who study CRISPR and other methods of gene editing call the reports “overblown.” They say the link to cancer is tenuous at best and an incorrect interpretation of the results at worst. “This is absurd,” John Doench, the associate director of the genetic perturbation platform at MIT’s Broad Institute, told Business Insider. “There was a massive overreaction here.”

Like many other researchers involved in the space, Doench read the two studieshighlighted in the recent report and published in the journal Nature Medicine. Instead of concluding that the technique causes cancer, Doench read the papers and thought it highlighted facts about how cells behave in response to perceived threats. Most of these are already fairly well-known to people who study gene editing. Tweaking a cell’s DNA is a violent process; when it is done, cells respond by trying to defend or repair themselves. This is one of the biggest hurdles facing most cutting-edge gene editing approaches today. It is not unique to CRISPR. “I’m honestly trying to figure out why this has generated such a response and I really can’t,” Doench said. “Everything I can see is just related to the stocks and finances and not in anyway related to the science.”

More here.

We sit side by side,

brother and sister, and read

the book of what will be, while a breeze

blows the pages over—

desolate odd, cheerful even,

and otherwise. When we come

to our own story, the happy beginning,

the ending we don’t know yet,

the ten thousand acts

encumbering the days between,

we will read every page of it.

If an ancestor has pressed

a love-flower for us, it will lie hidden

between pages of the slow going,

where only those who adore the story

ever read. When the time comes

to shut the book and set out,

we will take childhood’s laughter

as far as we can into the days to come,

until another laughter sounds back

from the place where our next bodies

will have risen and will be telling

tales of what seemed deadly serious once,

offering to us oldening wayfarers

the light heart, now made of time

and sorrow, that we started with.

by Galway Kinnell

from Collected Poems

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt