“It is the unforeseen end

and the nothing before.

I am in everything, and nothing is still

just the port of my dreams.”

………………….. —Juan Ramón Jiménez

Gilgamesh – Tablet IX

……………………….. iii

“Who is it comes here? Why have you journeyed

through fearful wilderness making your way though dangers

To come to the mountain no mortal has ever come to?”

Gilgamesh answered, his body seized in terror:

“I come to seek the answer to the question

that I must ask concerning life and death.

This is the way Gilgamesh must go,

weeping and fearful, struggling to keep breathing,

whether in heat or cold, companionless.

Open the gate to the center of the mountain.”

Then the Male Twin Monster said to Gilgamesh:

“The gate to the entrance of the mountain is open…”

After the Scorpion Dragon Being spoke,

Gilgamesh went to the entrance of the mountain

and entered the darkness alone, without a companion.

By the time he reached the end of the first league

the darkness was total, nothing behind or before.

He made his way, companionless, to the end

of the second league. Utterly lightless, black.

There was nothing behind or before, nothing at all.

Only, the blackness pressed upon his body.

He felt his blind way through the mountain tunnel,

struggling for breath, through the third league, alone,

and companionless through the fourth, making his way,

and struggling for every breath, to the end of the fifth,

in the absolute dark, nothing behind or before,

the weight of the blackness pressing in upon him.

Weeping and fearful he journeyed a sixth league,

Read more »

Many Palestinians would disagree on political grounds with my decision to watch Fauda. In fact, some have called for a boycott of the show. “It is an anti-Arab, racist, Israeli propaganda tool that glorifies the Israeli military’s war crimes against the Palestinian people,” the Palestinian-led Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions movement

Many Palestinians would disagree on political grounds with my decision to watch Fauda. In fact, some have called for a boycott of the show. “It is an anti-Arab, racist, Israeli propaganda tool that glorifies the Israeli military’s war crimes against the Palestinian people,” the Palestinian-led Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions movement  This is the

This is the

I’d been suffering under the misguided illusion that the purpose of mainstream publishers like Penguin Random House was to sell and promote fine writing. A colleague’s forwarded email has set me straight. Sent to a literary agent, presumably this letter was also fired off to the agents of the entire Penguin Random House stable. The email cites the publisher’s ‘new company-wide goal’: for ‘both our new hires and the authors we acquire to reflect UK society by 2025.’ (Gotta love that shouty boldface.) ‘This means we want our authors and new colleagues to reflect the UK population taking into account ethnicity, gender, sexuality, social mobility and disability.’ The email proudly proclaims that the company has removed ‘the need for a university degree from nearly all our jobs’ — which, if my manuscript were being copy-edited and proof-read by folks whose university-educated predecessors already exhibited horrifyingly weak grammar and punctuation, I would find alarming.

I’d been suffering under the misguided illusion that the purpose of mainstream publishers like Penguin Random House was to sell and promote fine writing. A colleague’s forwarded email has set me straight. Sent to a literary agent, presumably this letter was also fired off to the agents of the entire Penguin Random House stable. The email cites the publisher’s ‘new company-wide goal’: for ‘both our new hires and the authors we acquire to reflect UK society by 2025.’ (Gotta love that shouty boldface.) ‘This means we want our authors and new colleagues to reflect the UK population taking into account ethnicity, gender, sexuality, social mobility and disability.’ The email proudly proclaims that the company has removed ‘the need for a university degree from nearly all our jobs’ — which, if my manuscript were being copy-edited and proof-read by folks whose university-educated predecessors already exhibited horrifyingly weak grammar and punctuation, I would find alarming. The young men and women blowing clouds of grape and mint-flavoured smoke at a Middle Eastern shisha cafe in Sydney could pass for any group of friends.

The young men and women blowing clouds of grape and mint-flavoured smoke at a Middle Eastern shisha cafe in Sydney could pass for any group of friends. The chef, television host and author

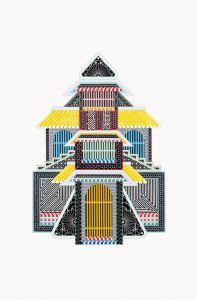

The chef, television host and author  It was in the third of the essays I was writing on how we’d come to see the cities of the future as cities of the future (something to refocus our attention on, now that the cities of the future of the past, the structures in which we were all living, had been thoroughly codified and photographed and renovated, resold as more shimmering or more minimalist versions of themselves then rephotographed, and we were liking the reiterations on our Instagrams, enjoying this incredible proximity to architecture: I was an architect, writing about architecture in my poems), but it was hard to deny that we’d reached that time in our respective chronologies when cities of the future was something that had to be reenvisioned and discussed as you sat under studio lights in a narrow room of books in an office building and your talk was broadcast over the Internet (you were not of the technological elite, so you didn’t know that sitting hunched over would make you appear hunched over to anybody watching), but the idea of cities of the future came to everyone one night in our sleep and it was time to begin to think and talk about it, to try to envision what these would look like and who would occupy them and if they would have different names or exist on different planets (you had to be speculative but also had to weigh in on what was actually happening on your streets, in your bodies, and between bodies): it was in number three of the essays that I began to see color as that which would make our cities of the future cities of the future and this was thanks to Edie Fake, whose renditions of the architectures of our new cities performed like an architecture finally taking into account our clothes. I began writing the essays about the cities of the future, starting with weather and invisibility—cities of the future, their weather; then cities of the future, invisibility—and I began each never considering that the cities of the future had color, and not only color but very bright color that was not only very bright but patterned as well.

It was in the third of the essays I was writing on how we’d come to see the cities of the future as cities of the future (something to refocus our attention on, now that the cities of the future of the past, the structures in which we were all living, had been thoroughly codified and photographed and renovated, resold as more shimmering or more minimalist versions of themselves then rephotographed, and we were liking the reiterations on our Instagrams, enjoying this incredible proximity to architecture: I was an architect, writing about architecture in my poems), but it was hard to deny that we’d reached that time in our respective chronologies when cities of the future was something that had to be reenvisioned and discussed as you sat under studio lights in a narrow room of books in an office building and your talk was broadcast over the Internet (you were not of the technological elite, so you didn’t know that sitting hunched over would make you appear hunched over to anybody watching), but the idea of cities of the future came to everyone one night in our sleep and it was time to begin to think and talk about it, to try to envision what these would look like and who would occupy them and if they would have different names or exist on different planets (you had to be speculative but also had to weigh in on what was actually happening on your streets, in your bodies, and between bodies): it was in number three of the essays that I began to see color as that which would make our cities of the future cities of the future and this was thanks to Edie Fake, whose renditions of the architectures of our new cities performed like an architecture finally taking into account our clothes. I began writing the essays about the cities of the future, starting with weather and invisibility—cities of the future, their weather; then cities of the future, invisibility—and I began each never considering that the cities of the future had color, and not only color but very bright color that was not only very bright but patterned as well. For all the talk of something disturbingly novel and unknown about a post-Trump world, with its crumbling trust in mainstream media and lack of faith in the institutions of democracy, there’s also something curiously retro about the whole thing. It’s not simply the US president himself, whose brash, greed-is-good confidence and private-jet-and-golden-tower personality were obnoxious enough the first time round, in the 1980s, nor his adoption of an outdated rhetoric of an America reawakened. It’s also in the rhetoric of his rivals, who have reached back to Cold War imagery of Soviet spy threats and reds under the bed when invoking the probable Russian interference in the 2016 US election. It’s not just collusion in Trump’s campaign they’re warning of. It’s also a return to that seemingly most Soviet of influences – Russian propaganda – finding its way into the innocent homes of the American people. Twitter bots, online trolls and “fake news” have all been described as modern propaganda, updated versions of the bold posters and misleading pamphlets of official Stalinist culture. Their role, it’s claimed, is nothing less than undermining truth and knowledge itself, the values on which democratic culture is built. How did propaganda get such a bad name?

For all the talk of something disturbingly novel and unknown about a post-Trump world, with its crumbling trust in mainstream media and lack of faith in the institutions of democracy, there’s also something curiously retro about the whole thing. It’s not simply the US president himself, whose brash, greed-is-good confidence and private-jet-and-golden-tower personality were obnoxious enough the first time round, in the 1980s, nor his adoption of an outdated rhetoric of an America reawakened. It’s also in the rhetoric of his rivals, who have reached back to Cold War imagery of Soviet spy threats and reds under the bed when invoking the probable Russian interference in the 2016 US election. It’s not just collusion in Trump’s campaign they’re warning of. It’s also a return to that seemingly most Soviet of influences – Russian propaganda – finding its way into the innocent homes of the American people. Twitter bots, online trolls and “fake news” have all been described as modern propaganda, updated versions of the bold posters and misleading pamphlets of official Stalinist culture. Their role, it’s claimed, is nothing less than undermining truth and knowledge itself, the values on which democratic culture is built. How did propaganda get such a bad name? It is easy to make anyone look moronic or sinister when you control the means of their representation. It is trivially easy to hang someone by their own words when you control where the sentences

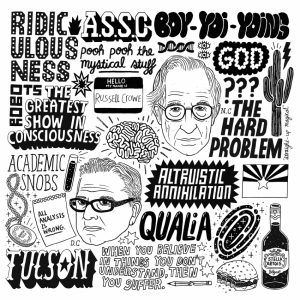

It is easy to make anyone look moronic or sinister when you control the means of their representation. It is trivially easy to hang someone by their own words when you control where the sentences  Start with Noam Chomsky, Deepak Chopra, and a robot that loves you no matter what. Add a knighted British physicist, a renowned French neuroscientist, and a prominent Australian philosopher/occasional blues singer. Toss in a bunch of psychologists, mathematicians, anesthesiologists, artists, meditators, a computer programmer or two, and several busloads of amateur theorists waving self-published manuscripts and touting grand unified solutions. Send them all to a swanky resort in the desert for a week, supply them with lots of free coffee and beer, and ask them to unpack a riddle so confounding that it’s unclear how to make progress or where you’d even begin.

Start with Noam Chomsky, Deepak Chopra, and a robot that loves you no matter what. Add a knighted British physicist, a renowned French neuroscientist, and a prominent Australian philosopher/occasional blues singer. Toss in a bunch of psychologists, mathematicians, anesthesiologists, artists, meditators, a computer programmer or two, and several busloads of amateur theorists waving self-published manuscripts and touting grand unified solutions. Send them all to a swanky resort in the desert for a week, supply them with lots of free coffee and beer, and ask them to unpack a riddle so confounding that it’s unclear how to make progress or where you’d even begin. Peter Woit is

Peter Woit is As the World Cup begins next week in Russia,

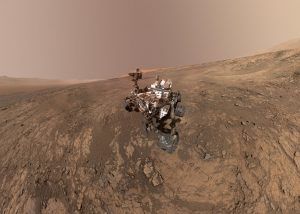

As the World Cup begins next week in Russia,  In a much-hyped press conference held on Thursday, NASA announced its Curiosity rover had uncovered new evidence of methane — a potential sign of life — as well as signs of organic compounds buried in ancient mudstone. The space agency did not say it had found evidence of alien life. However, these new results are still tantalizing. Curiosity landed on Mars back in 2012 and it’s been slowly climbing up Mount Sharp, a large hill formed when an asteroid impact created Gale Crater, simultaneously exposing multi-billion year old sedimentary rocks laid down in an ancient lakebed. The rover came equipped with a suite of instruments known as Sample Analysis at Mars, or SAM. And its main goal was to find organic molecules. These commonly form in non-biological processes, but they’re also the building blocks of life. And mysteriously, the VW Beetle-sized rover succeeded in finding organics even though past Mars missions, like 1976’s Viking landers, did not. This latest announcement was tied to two scientific papers published simultaneously in the prestigious journal Science. One study focused on the methane and the other looked at the organics.

In a much-hyped press conference held on Thursday, NASA announced its Curiosity rover had uncovered new evidence of methane — a potential sign of life — as well as signs of organic compounds buried in ancient mudstone. The space agency did not say it had found evidence of alien life. However, these new results are still tantalizing. Curiosity landed on Mars back in 2012 and it’s been slowly climbing up Mount Sharp, a large hill formed when an asteroid impact created Gale Crater, simultaneously exposing multi-billion year old sedimentary rocks laid down in an ancient lakebed. The rover came equipped with a suite of instruments known as Sample Analysis at Mars, or SAM. And its main goal was to find organic molecules. These commonly form in non-biological processes, but they’re also the building blocks of life. And mysteriously, the VW Beetle-sized rover succeeded in finding organics even though past Mars missions, like 1976’s Viking landers, did not. This latest announcement was tied to two scientific papers published simultaneously in the prestigious journal Science. One study focused on the methane and the other looked at the organics. Well, why does anyone take drugs? The simplest answer is that drugs are generally fun to take, until they aren’t. But psychedelics are different. They don’t drape you in marijuana’s gauzy haze or imbue you with cocaine’s wintry, italicized focus. They’re nothing like opioids, which balance the human body on a knife’s edge between pleasure and death. Psychedelics are to drugs what the Pyramids are to architecture — majestic, ancient and a little frightening. Pollan persuasively argues that our anxieties are misplaced when it comes to psychedelics, most of which are nonaddictive. They also fail to produce what Pollan calls the “physiological noise” of other psychoactive drugs. All things considered, LSD is probably less harmful to the human body than Diet Dr Pepper.

Well, why does anyone take drugs? The simplest answer is that drugs are generally fun to take, until they aren’t. But psychedelics are different. They don’t drape you in marijuana’s gauzy haze or imbue you with cocaine’s wintry, italicized focus. They’re nothing like opioids, which balance the human body on a knife’s edge between pleasure and death. Psychedelics are to drugs what the Pyramids are to architecture — majestic, ancient and a little frightening. Pollan persuasively argues that our anxieties are misplaced when it comes to psychedelics, most of which are nonaddictive. They also fail to produce what Pollan calls the “physiological noise” of other psychoactive drugs. All things considered, LSD is probably less harmful to the human body than Diet Dr Pepper. Anthony Bourdain, whose madcap memoir about the dark corners of New York’s restaurants made him into a celebrity chef and touched off a nearly two-decade career as a globe-trotting television host, was found dead in his hotel room in France on Friday. He was 61.

Anthony Bourdain, whose madcap memoir about the dark corners of New York’s restaurants made him into a celebrity chef and touched off a nearly two-decade career as a globe-trotting television host, was found dead in his hotel room in France on Friday. He was 61.