Adam Rutherford in New Statesman:

I have spent much of the last few days destroying my own work. It turns out that obliterating it neatly is almost as difficult as making it. It’s publication week of my latest, The Book of Humans, and we’ve been running various competitions to draw people’s eyes in. I have great fondness for hiding secrets in my books. In one, I encoded a message in the letters of the genetic code – an email address that revealed the instructions for a treasure hunt. For The Book of Humans – surely conceived by me as an epic act of procrastination – I have dug out a hole in the middle of one copy, as if to hide a wad of cash, and inside this book-box I’ve stashed a small treasure, something mentioned in the book and of relevance to the story. So far, I’ve destroyed two practice copies with a multi-tool trying to carve and glue a neat rectangular box inside 250 pages of human evolution. I’ll push the button for this hunt to begin on Twitter this week. Let’s see how long it takes people to work out what’s in the box.

I have spent much of the last few days destroying my own work. It turns out that obliterating it neatly is almost as difficult as making it. It’s publication week of my latest, The Book of Humans, and we’ve been running various competitions to draw people’s eyes in. I have great fondness for hiding secrets in my books. In one, I encoded a message in the letters of the genetic code – an email address that revealed the instructions for a treasure hunt. For The Book of Humans – surely conceived by me as an epic act of procrastination – I have dug out a hole in the middle of one copy, as if to hide a wad of cash, and inside this book-box I’ve stashed a small treasure, something mentioned in the book and of relevance to the story. So far, I’ve destroyed two practice copies with a multi-tool trying to carve and glue a neat rectangular box inside 250 pages of human evolution. I’ll push the button for this hunt to begin on Twitter this week. Let’s see how long it takes people to work out what’s in the box.

Schrödinger’s chat

I’m writing these words on a plane to London from Dublin, where a bunch of scientists were celebrating the 75th anniversary of one of the most influential series of lectures of the 20th century. You may have heard of the Nobel-winning physicist Erwin Schrödinger from his thought experiment – no real animals were harmed – in which a cat in a sealed box was simultaneously dead and alive until observed, whereon it chose one of those quantum states. I forget why this is important, because as a mere biologist, I am primarily concerned with organisms that are either alive or dead, but never both.

More here.

“You’re dead,” said the meditation guide. “You’ve been dead a long time.” I start crying. “What do you see?” she asked. I whimpered, “My dad somewhere, cremated, maybe a river, gone for decades. My son is older. He has a family. He thinks of me sometimes. I can’t stand it.”

“You’re dead,” said the meditation guide. “You’ve been dead a long time.” I start crying. “What do you see?” she asked. I whimpered, “My dad somewhere, cremated, maybe a river, gone for decades. My son is older. He has a family. He thinks of me sometimes. I can’t stand it.” In the beginning was the map.

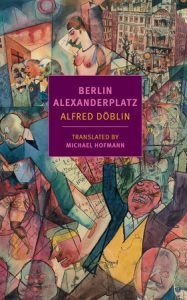

In the beginning was the map.  In the tempest-plagued teapot of English translation, Michael Hofmann’s dust-ups are notorious: he compared Stefan Zweig’s suicide note to an Oscar acceptance speech, eviscerated James Reidel’s translations of Thomas Bernhard’s poems, brushed off George Konrad’s A Feast in the Garden as “dire… export-quality horseshit.” Critics seem generally pleased with his translations, but then, critics like Toril Moi, Tim Parks, or Hofmann himself—that is to say, those willing and able to scrutinize the changes a text in translation undergoes, and the details of what is gained and lost alone the way—are rare, and the newspaper reviewer’s “cleverly translated,” “serviceably translated,” and suchlike don’t count for too much. Readers I know are not of one mind about his work: some are unqualified fans, particularly of Angina Days, his selected poetry of Günter Eich. What seems to grate on the less enthusiastic are his translations’ motley surfaces, the “occasional rhinestones or bits of jet,” as he has it in one interview, which mark them, not as the pellucid transmigration of the author’s inspiration from source language into target, but as a patent contrivance in the latter.

In the tempest-plagued teapot of English translation, Michael Hofmann’s dust-ups are notorious: he compared Stefan Zweig’s suicide note to an Oscar acceptance speech, eviscerated James Reidel’s translations of Thomas Bernhard’s poems, brushed off George Konrad’s A Feast in the Garden as “dire… export-quality horseshit.” Critics seem generally pleased with his translations, but then, critics like Toril Moi, Tim Parks, or Hofmann himself—that is to say, those willing and able to scrutinize the changes a text in translation undergoes, and the details of what is gained and lost alone the way—are rare, and the newspaper reviewer’s “cleverly translated,” “serviceably translated,” and suchlike don’t count for too much. Readers I know are not of one mind about his work: some are unqualified fans, particularly of Angina Days, his selected poetry of Günter Eich. What seems to grate on the less enthusiastic are his translations’ motley surfaces, the “occasional rhinestones or bits of jet,” as he has it in one interview, which mark them, not as the pellucid transmigration of the author’s inspiration from source language into target, but as a patent contrivance in the latter. “The trouble with life (the novelist will feel) is its amorphousness, its ridiculous fluidity,” writes Martin Amis in his memoir Experience. “Look at it: thinly plotted, largely themeless, sentimental and ineluctably trite. The dialogue is poor, or at least violently uneven. The twists are predictable or sensationalist. And it’s always the same beginning; and the same ending…”

“The trouble with life (the novelist will feel) is its amorphousness, its ridiculous fluidity,” writes Martin Amis in his memoir Experience. “Look at it: thinly plotted, largely themeless, sentimental and ineluctably trite. The dialogue is poor, or at least violently uneven. The twists are predictable or sensationalist. And it’s always the same beginning; and the same ending…”

I can make a

I can make a  I met

I met  Homi Bhabha:

Homi Bhabha:

When the novel “Washington Black” opens, it is 1830 and the young George Washington Black, who narrates his own story, is a slave on a Barbados sugar plantation called Faith, protected, or at least watched over, by an older woman, Big Kit. As a new master takes charge, the fear is palpable. The accounts of murders and punishments and random cruelties are chilling and unsparing. Big Kit can see no way out except death: “Death was a door. I think that is what she wished me to understand. She did not fear it. She was of an ancient faith rooted in the high river lands of Africa, and in that faith the dead were reborn, whole, back in their homelands, to walk again free.” The reader can almost see what is coming. Since Barbados was under British rule, slavery was abolished there in 1834. This, then, could be a novel about the last days of the cruelty, about what happens to a slave-owning family and to the slaves during the waning of the old dispensation.

When the novel “Washington Black” opens, it is 1830 and the young George Washington Black, who narrates his own story, is a slave on a Barbados sugar plantation called Faith, protected, or at least watched over, by an older woman, Big Kit. As a new master takes charge, the fear is palpable. The accounts of murders and punishments and random cruelties are chilling and unsparing. Big Kit can see no way out except death: “Death was a door. I think that is what she wished me to understand. She did not fear it. She was of an ancient faith rooted in the high river lands of Africa, and in that faith the dead were reborn, whole, back in their homelands, to walk again free.” The reader can almost see what is coming. Since Barbados was under British rule, slavery was abolished there in 1834. This, then, could be a novel about the last days of the cruelty, about what happens to a slave-owning family and to the slaves during the waning of the old dispensation. Sally Horner was a widow’s daughter, a brown-haired honor student, from Camden, New Jersey. In 1948, hoping to impress some popular girls, she nicked a notebook from a dime store and was accosted by a man, Frank La Salle, posing as an F.B.I. agent. La Salle, who told Horner his name was Frank Warren, informed the eleven-year-old that he was placing her under surveillance. Then he commanded her to take a bus with him to Atlantic City, and from there they embarked on a cross-country road trip. Like Humbert Humbert, the protagonist of the novel “

Sally Horner was a widow’s daughter, a brown-haired honor student, from Camden, New Jersey. In 1948, hoping to impress some popular girls, she nicked a notebook from a dime store and was accosted by a man, Frank La Salle, posing as an F.B.I. agent. La Salle, who told Horner his name was Frank Warren, informed the eleven-year-old that he was placing her under surveillance. Then he commanded her to take a bus with him to Atlantic City, and from there they embarked on a cross-country road trip. Like Humbert Humbert, the protagonist of the novel “ In a report

In a report  It has been a year since Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico, leaving a trail of destruction: ruined infrastructure, destroyed homes, and thousands of fatalities. Since that particular hurricane has largely faded from the news, the slow rebuild continues and defining questions loom over the process: Who is Puerto Rico for? Outside investors and tourists or Puerto Ricans? After a collective trauma like Hurricane Maria, who has the right to decide for Puerto Rico? The fight for its future is underway.

It has been a year since Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico, leaving a trail of destruction: ruined infrastructure, destroyed homes, and thousands of fatalities. Since that particular hurricane has largely faded from the news, the slow rebuild continues and defining questions loom over the process: Who is Puerto Rico for? Outside investors and tourists or Puerto Ricans? After a collective trauma like Hurricane Maria, who has the right to decide for Puerto Rico? The fight for its future is underway.