by Samia Altaf

In the 1960s, in the sleepy little city of Sialkot, almost in no-man’s land between India and Pakistan and of little significance except for its large cantonment and its factories of surgical instruments and sports goods, there were two cinema houses, all within a mile of our house, No. 3 Kutchery Road. Well three to be exact, the third being an improvisation involving two tree trunks with a white sheet slung between them at the Services club and only on Saturday nights.

In the 1960s, in the sleepy little city of Sialkot, almost in no-man’s land between India and Pakistan and of little significance except for its large cantonment and its factories of surgical instruments and sports goods, there were two cinema houses, all within a mile of our house, No. 3 Kutchery Road. Well three to be exact, the third being an improvisation involving two tree trunks with a white sheet slung between them at the Services club and only on Saturday nights.

The one closest to us our house, just this side of the railway crossing, was Nishat, popularly known as Begum’s cinema with a risqué aura because it was owned and managed by the ‘Begum,’ a burqa-clad, not so young, but still beautiful woman. There was hushed talk about the Begum’s morals because she, a single woman, owned and managed a cinema house in a time when so-called ‘decent’ women rarely went to the cinema let alone own one.

The second, past the railway crossing on the other side of the ‘drumma wallah chowk,’ the main city square, was the Lalazar. Lalazar was considered to be in a class above the others partly for its sweeping marble staircase curving upwards to the gallery and partly for its owner Mr. Majeed’s newly acquired daughter-in-law Mussarat Nazir, the rustic Punjabi beauty and a leading lady of film industry. Mr. Majeed, a portly gentleman with a loud laugh, was among the city fathers, the ‘shurafa,’ of the city. Mussarat Nazeer, still in her teens, came to public attention in the movie Yakkey Wali. My father tells how he and his friends, all grown and married men, saw that movie about twenty times and every time M. Nazir appeared on screen, they along with the whole house threw coins at the screen in the age old tradition of showing one’s appreciation. M. Nazir’s untimely departure at the height of her career to lead a life of married bliss in Canada was mourned by all till she returned thirty years later, still the rustic beauty, and became a household name selling millions of audio cassettes of Punjabi wedding and folk songs. My older son, then three years old, heard her signature folk song ‘Laung gwacha,’ saw her face on the grimy cover of a much used audio cassette, fell immediately in love and vowed to marry her. His grandfather understood completely. Read more »

The word “Chinko” means nothing. It is the name given to a river in a place where the river gets lost in thick brush and fields of termite mounds. Chinko Park, established to protect what little is left, is called a national park, but there is nothing national in a place without the rule of law. Chinko’s only defense is a handful of well-trained rangers who spend weeks at a time in the wild, waiting for poachers or armed groups to emerge from the thick bush and attack. This is a dangerous part of the world—everyone knows at least that much.

The word “Chinko” means nothing. It is the name given to a river in a place where the river gets lost in thick brush and fields of termite mounds. Chinko Park, established to protect what little is left, is called a national park, but there is nothing national in a place without the rule of law. Chinko’s only defense is a handful of well-trained rangers who spend weeks at a time in the wild, waiting for poachers or armed groups to emerge from the thick bush and attack. This is a dangerous part of the world—everyone knows at least that much.

On December 31,

On December 31,  The

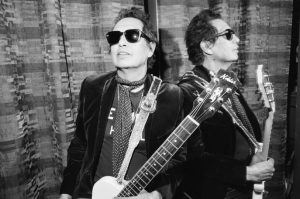

The Alejandro Escovedo, the singer and songwriter, likes to have a proper Mexican breakfast before a long drive. “Let’s go here,” he said. He pulled into the back lot of a restaurant called El Pueblo, across from the Tornado bus terminal on East Jefferson Boulevard, in the Oak Cliff section of Dallas. El Pueblo, he said, is where travellers arriving by bus from Mexico often go to eat and to get their bearings. He ordered in Spanish, then remarked that his Spanish was poor. The plates came quickly. Chorizo con huevos. “This is bad_ass_, man,” he said. An elderly vagrant looked in through the window and then walked in. Escovedo gave him a dollar. “When I was small, I used to be able to see the pain in people,” he said.

Alejandro Escovedo, the singer and songwriter, likes to have a proper Mexican breakfast before a long drive. “Let’s go here,” he said. He pulled into the back lot of a restaurant called El Pueblo, across from the Tornado bus terminal on East Jefferson Boulevard, in the Oak Cliff section of Dallas. El Pueblo, he said, is where travellers arriving by bus from Mexico often go to eat and to get their bearings. He ordered in Spanish, then remarked that his Spanish was poor. The plates came quickly. Chorizo con huevos. “This is bad_ass_, man,” he said. An elderly vagrant looked in through the window and then walked in. Escovedo gave him a dollar. “When I was small, I used to be able to see the pain in people,” he said. When I was 11, I read Little

When I was 11, I read Little

Recently, CNN sent their reporter to cover yet another Trump rally (in Pennsylvania), but this time reporter Gary Tuchman was assigned the more specific task of interviewing Trump supporters who were carrying signs or large cardboard cut-outs of the letter “Q” and wearing T-shirts proclaiming “We are Q”.

Recently, CNN sent their reporter to cover yet another Trump rally (in Pennsylvania), but this time reporter Gary Tuchman was assigned the more specific task of interviewing Trump supporters who were carrying signs or large cardboard cut-outs of the letter “Q” and wearing T-shirts proclaiming “We are Q”. In the 1960s, in the sleepy little city of Sialkot, almost in no-man’s land between India and Pakistan and of little significance except for its large cantonment and its factories of surgical instruments and sports goods, there were two cinema houses, all within a mile of our house, No. 3 Kutchery Road. Well three to be exact, the third being an improvisation involving two tree trunks with a white sheet slung between them at the Services club and only on Saturday nights.

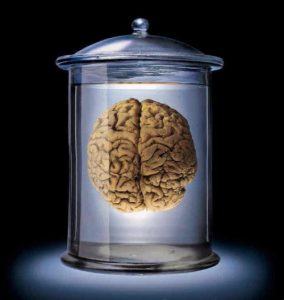

In the 1960s, in the sleepy little city of Sialkot, almost in no-man’s land between India and Pakistan and of little significance except for its large cantonment and its factories of surgical instruments and sports goods, there were two cinema houses, all within a mile of our house, No. 3 Kutchery Road. Well three to be exact, the third being an improvisation involving two tree trunks with a white sheet slung between them at the Services club and only on Saturday nights. Would I rather go deaf or blind? Every once in a while, I come back to this question in some version or another. Say I had to choose which sense I’d lose in my old age, which would it be? I always give myself, unequivocally, the same answer: I’d rather go blind. I’d rather my world go darker than quieter. I imagine it as a choice between seeing the world and communicating with it; in this hypothetical, communication with the world is all-encompassing, its loss more devastating than the loss of sight. It is perhaps clear from the mere fact that I pose this question that I do not live with a disability involving the senses. Individuals who are vision- or hearing-impaired would have an entirely different take on this question and on the issues I raise below, but hopefully what I write here will go beyond stating my own prejudices.

Would I rather go deaf or blind? Every once in a while, I come back to this question in some version or another. Say I had to choose which sense I’d lose in my old age, which would it be? I always give myself, unequivocally, the same answer: I’d rather go blind. I’d rather my world go darker than quieter. I imagine it as a choice between seeing the world and communicating with it; in this hypothetical, communication with the world is all-encompassing, its loss more devastating than the loss of sight. It is perhaps clear from the mere fact that I pose this question that I do not live with a disability involving the senses. Individuals who are vision- or hearing-impaired would have an entirely different take on this question and on the issues I raise below, but hopefully what I write here will go beyond stating my own prejudices. The idea of ‘good corporate citizenship’ has become popular recently among business ethicists and corporate leaders. You may have noticed its appearance on corporate websites and CEO speeches. But what does it mean and does it matter? Is it any more than a new species of public relations flimflam to set beside terms like ‘corporate social responsibility’ and the ‘triple bottom line’? Is it just a metaphor?

The idea of ‘good corporate citizenship’ has become popular recently among business ethicists and corporate leaders. You may have noticed its appearance on corporate websites and CEO speeches. But what does it mean and does it matter? Is it any more than a new species of public relations flimflam to set beside terms like ‘corporate social responsibility’ and the ‘triple bottom line’? Is it just a metaphor? Learning Objectives. Measurable Outcomes. These are among the buzziest of buzz words in current debates about education. And that discordant groaning noise you can hear around many academic departments is the sound of recalcitrant faculty, following orders from on high, unenthusiastically inserting learning objectives (henceforth LOs) and measurable outcomes (hereafter MOs) into already bloated syllabi or program assessment instruments.

Learning Objectives. Measurable Outcomes. These are among the buzziest of buzz words in current debates about education. And that discordant groaning noise you can hear around many academic departments is the sound of recalcitrant faculty, following orders from on high, unenthusiastically inserting learning objectives (henceforth LOs) and measurable outcomes (hereafter MOs) into already bloated syllabi or program assessment instruments.

One of the problems in discussing censorship is that we often don’t recognize censorship for what it is. There is no longer the Lord Chamberlain marking scripts and cutting out the unacceptable. Instead, we, in effect, ourselves mark them. And that, ironically, makes censorship not more, but less, visible.

One of the problems in discussing censorship is that we often don’t recognize censorship for what it is. There is no longer the Lord Chamberlain marking scripts and cutting out the unacceptable. Instead, we, in effect, ourselves mark them. And that, ironically, makes censorship not more, but less, visible. Around 558 million years ago, a strange … something dies on the floor of an ancient ocean. Its body, if you could call it that, is a two-inch-long oval with symmetric ribs running from its midline to its fringes. It is quickly buried in sediment, and gradually turns into a fossil.

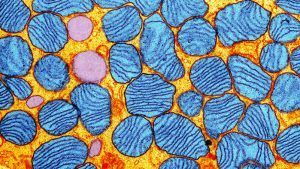

Around 558 million years ago, a strange … something dies on the floor of an ancient ocean. Its body, if you could call it that, is a two-inch-long oval with symmetric ribs running from its midline to its fringes. It is quickly buried in sediment, and gradually turns into a fossil. Warnings about ecological breakdown have become ubiquitous. Over the past few years, major newspapers, including the Guardian and the New York Times, have carried alarming stories on soil depletion, deforestation, and the collapse of fish stocks and insect populations. These crises are being driven by global economic growth, and its accompanying consumption, which is destroying the Earth’s biosphere and blowing past key planetary boundaries that scientists say must be respected to avoid triggering collapse.

Warnings about ecological breakdown have become ubiquitous. Over the past few years, major newspapers, including the Guardian and the New York Times, have carried alarming stories on soil depletion, deforestation, and the collapse of fish stocks and insect populations. These crises are being driven by global economic growth, and its accompanying consumption, which is destroying the Earth’s biosphere and blowing past key planetary boundaries that scientists say must be respected to avoid triggering collapse. It was entirely a coincidence that I found myself reading Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff’s

It was entirely a coincidence that I found myself reading Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff’s