Emily Temple in Literary Hub:

In 1921, 24-year-old William Faulkner had dropped out of the University of Mississippi (for the second time) and was living in Greenwich Village, working in a bookstore—but he was getting restless. Eventually, his mentor, Phil Stone, an Oxford attorney, arranged for him to be appointed postmaster at the school he had only recently left. He was paid a salary of $1,700 in 1922 and $1,800 in the following years, but it’s unclear how he came by that raise, because by all accounts he was uniquely terrible at his job. “I forced Bill to take the job over his own declination and refusal,” Stone said later, according to David Minter’s biography. “He made the damndest postmaster the world has ever seen.”

In 1921, 24-year-old William Faulkner had dropped out of the University of Mississippi (for the second time) and was living in Greenwich Village, working in a bookstore—but he was getting restless. Eventually, his mentor, Phil Stone, an Oxford attorney, arranged for him to be appointed postmaster at the school he had only recently left. He was paid a salary of $1,700 in 1922 and $1,800 in the following years, but it’s unclear how he came by that raise, because by all accounts he was uniquely terrible at his job. “I forced Bill to take the job over his own declination and refusal,” Stone said later, according to David Minter’s biography. “He made the damndest postmaster the world has ever seen.”

Faulkner would open and close the office whenever he felt like it, he would read other people’s magazines, he would throw out any mail he thought unimportant, he would play cards with his friends or write in the back while patrons waited out front. A comic in the student publication Ole Miss in 1922 showed a picture of Faulkner and the post office, calling it the “Postgraduate Club. Hours: 11:30 to 12:30 every Wednesday. Motto: Never put the mail up on time. Aim: Develop postmasters out of fifty students every year.”

More here.

When René Descartes was 31 years old, in 1627, he began to write a manifesto on the proper methods of philosophising. He chose the title Regulae ad Directionem Ingenii, or Rules for the Direction of the Mind. It is a curious work. Descartes originally intended to present 36 rules divided evenly into three parts, but the manuscript trails off in the middle of the second part. Each rule was to be set forth in one or two sentences followed by a lengthy elaboration. The first rule tells us that ‘The end of study should be to direct the mind to an enunciation of sound and correct judgments on all matters that come before it,’ and the third rule tells us that ‘Our enquiries should be directed, not to what others have thought … but to what we can clearly and perspicuously behold and with certainty deduce.’ Rule four tells us that ‘There is a need of a method for finding out the truth.’

When René Descartes was 31 years old, in 1627, he began to write a manifesto on the proper methods of philosophising. He chose the title Regulae ad Directionem Ingenii, or Rules for the Direction of the Mind. It is a curious work. Descartes originally intended to present 36 rules divided evenly into three parts, but the manuscript trails off in the middle of the second part. Each rule was to be set forth in one or two sentences followed by a lengthy elaboration. The first rule tells us that ‘The end of study should be to direct the mind to an enunciation of sound and correct judgments on all matters that come before it,’ and the third rule tells us that ‘Our enquiries should be directed, not to what others have thought … but to what we can clearly and perspicuously behold and with certainty deduce.’ Rule four tells us that ‘There is a need of a method for finding out the truth.’

Emmy Noether was a force in mathematics — and knew it. She was fully confident in her capabilities and ideas. Yet a century on, those ideas, and their contribution to science, often go unnoticed. Most physicists are aware of her fundamental theorem, which puts symmetry at the heart of physical law. But how many know anything of her and her life?

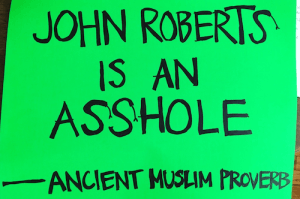

Emmy Noether was a force in mathematics — and knew it. She was fully confident in her capabilities and ideas. Yet a century on, those ideas, and their contribution to science, often go unnoticed. Most physicists are aware of her fundamental theorem, which puts symmetry at the heart of physical law. But how many know anything of her and her life? When last June we heard about the kids arriving in New York from the Southern border—the first moment the child separation policy flared into the public eye, the first I knew of its systematic existence—we raced to LaGuardia to witness, to support, to stage something visible, at least. We made posters on the M60 bus. I passed around fat sharpies, brought extra neon poster-board. No one knew what to write, or who to address. The children? Their captors? The news cameras? It maybe wasn’t a great decision. The couple of kids I saw filing out of side doors were so little and tired and quiet. I’m not sure a phalanx of screaming adults helped, though it gave the TV cameras something to show other than their tiny bodies. Some stubborn questioners managed to get information about where the children were being taken in the unmarked vans.

When last June we heard about the kids arriving in New York from the Southern border—the first moment the child separation policy flared into the public eye, the first I knew of its systematic existence—we raced to LaGuardia to witness, to support, to stage something visible, at least. We made posters on the M60 bus. I passed around fat sharpies, brought extra neon poster-board. No one knew what to write, or who to address. The children? Their captors? The news cameras? It maybe wasn’t a great decision. The couple of kids I saw filing out of side doors were so little and tired and quiet. I’m not sure a phalanx of screaming adults helped, though it gave the TV cameras something to show other than their tiny bodies. Some stubborn questioners managed to get information about where the children were being taken in the unmarked vans. Cicadas might be a pest, but they’re special in a few respects. For one, these droning insects have a habit of emerging after a prime number of years (7, 13, or 17). They also feed exclusively on plant sap, which is strikingly low in nutrients. To make up for this deficiency, cicadas depend on two different strains of bacteria that they keep cloistered within special cells, and that provide them with additional amino acids. All three partners – the cicadas and the two types of microbes – have evolved in concert, and none could survive on its own. These organisms together make up what’s

Cicadas might be a pest, but they’re special in a few respects. For one, these droning insects have a habit of emerging after a prime number of years (7, 13, or 17). They also feed exclusively on plant sap, which is strikingly low in nutrients. To make up for this deficiency, cicadas depend on two different strains of bacteria that they keep cloistered within special cells, and that provide them with additional amino acids. All three partners – the cicadas and the two types of microbes – have evolved in concert, and none could survive on its own. These organisms together make up what’s  “Look at me when I’m talking to you! You’re telling me that my assault doesn’t matter. That what happened to me doesn’t matter!” Those anguished words came from Maria Gallagher, who, along with Ana Maria Archila,

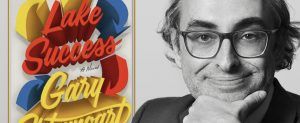

“Look at me when I’m talking to you! You’re telling me that my assault doesn’t matter. That what happened to me doesn’t matter!” Those anguished words came from Maria Gallagher, who, along with Ana Maria Archila,  In 2016, Russian born novelist Gary Shteyngart took a bus ride. It was an uncertain time in American culture and politics, and Shteyngart, who’s won a devoted following for his bestsellers “Absurdistan, “Super Sad True Love Story” and the memoir “Little Failure,” didn’t know what would come of the journey. Two years later, he’s emerged with not just the first big novel of the post-Obama era, but the first truly great novel of it.

In 2016, Russian born novelist Gary Shteyngart took a bus ride. It was an uncertain time in American culture and politics, and Shteyngart, who’s won a devoted following for his bestsellers “Absurdistan, “Super Sad True Love Story” and the memoir “Little Failure,” didn’t know what would come of the journey. Two years later, he’s emerged with not just the first big novel of the post-Obama era, but the first truly great novel of it. Transhumanism (also abbreviated as H+) is a philosophical movement which advocates for technology not only enhancing human life, but to take over human life by merging human and machine. The idea is that in one future day, humans will be vastly more intelligent, healthy, and physically powerful. In fact, much of this movement is based upon the notion that death is not an option with a focus to improve the somatic body and make humans immortal.

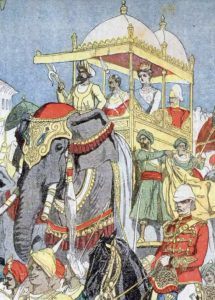

Transhumanism (also abbreviated as H+) is a philosophical movement which advocates for technology not only enhancing human life, but to take over human life by merging human and machine. The idea is that in one future day, humans will be vastly more intelligent, healthy, and physically powerful. In fact, much of this movement is based upon the notion that death is not an option with a focus to improve the somatic body and make humans immortal. On 24 September 1599, while William Shakespeare was mulling over a draft of Hamlet in his house downriver from the Globe in Southwark, a mile to the north a motley group of Londoners were gathering in a half-timbered Tudor hall. The men had come together to petition the ageing Elizabeth I, then a bewigged and painted sexagenarian, to start up a company “to venter in a voiage to ye Est Indies”.

On 24 September 1599, while William Shakespeare was mulling over a draft of Hamlet in his house downriver from the Globe in Southwark, a mile to the north a motley group of Londoners were gathering in a half-timbered Tudor hall. The men had come together to petition the ageing Elizabeth I, then a bewigged and painted sexagenarian, to start up a company “to venter in a voiage to ye Est Indies”. In “Duende” and in her third book, the Pulitzer Prize-winning “

In “Duende” and in her third book, the Pulitzer Prize-winning “ Some of the biggest names in English letters, including

Some of the biggest names in English letters, including  Watching Blasey Ford’s opening statement and questioning this morning before an almost entirely male panel, I am more sure than ever that she is telling the truth. Either that, or she is a better character actor than Meryl Streep. There are no serious grounds to believe that this is a case of mistaken identity either. Nothing in Blasey Ford’s demeanour, her statements or her responses suggested that she is doing anything other than telling the truth. Everything about her traumatised manner, her detailed statements and responses has the ring of credibility. As Democratic senator Sheldon Whitehouse of Rhode Island said, her account matches prosecutorial standards of ’preliminary credibility’, and its details are ‘consistent with the known facts’. Everything in Blasey Ford’s account also accords with what everyone who moves in circles associated with ‘elite prep schools’ — and ‘elite’ universities too — knows is a serious problem in male behaviour. The problem has two faces, the entitlement of spoilt princelings, and its supercharging by heavy drinking into forms of dangerous and criminal idiocy. This kind of perverted male camaraderie is not high spirits, unless high spirits is the ‘uproarious laughter’ of two boys as one of them assaults a 15-year old girl.

Watching Blasey Ford’s opening statement and questioning this morning before an almost entirely male panel, I am more sure than ever that she is telling the truth. Either that, or she is a better character actor than Meryl Streep. There are no serious grounds to believe that this is a case of mistaken identity either. Nothing in Blasey Ford’s demeanour, her statements or her responses suggested that she is doing anything other than telling the truth. Everything about her traumatised manner, her detailed statements and responses has the ring of credibility. As Democratic senator Sheldon Whitehouse of Rhode Island said, her account matches prosecutorial standards of ’preliminary credibility’, and its details are ‘consistent with the known facts’. Everything in Blasey Ford’s account also accords with what everyone who moves in circles associated with ‘elite prep schools’ — and ‘elite’ universities too — knows is a serious problem in male behaviour. The problem has two faces, the entitlement of spoilt princelings, and its supercharging by heavy drinking into forms of dangerous and criminal idiocy. This kind of perverted male camaraderie is not high spirits, unless high spirits is the ‘uproarious laughter’ of two boys as one of them assaults a 15-year old girl. Even in comparison to other types of cancer, brain cancer is particularly deadly. People with glioblastoma multiforme, one of the most common forms of brain cancer, have a median survival of less than 15 months after diagnosis. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has so far approved only five drugs for treating brain cancer. Given this limited range, researchers could search for potential treatments among the wider pool of all FDA-approved drugs; however, any found to be effective would probably work in just a slim percentage of people with brain cancer.

Even in comparison to other types of cancer, brain cancer is particularly deadly. People with glioblastoma multiforme, one of the most common forms of brain cancer, have a median survival of less than 15 months after diagnosis. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has so far approved only five drugs for treating brain cancer. Given this limited range, researchers could search for potential treatments among the wider pool of all FDA-approved drugs; however, any found to be effective would probably work in just a slim percentage of people with brain cancer. Ever since completing his Ph.D. at the University of Pittsburgh in 1993, the Israeli philosopher Irad Kimhi has been building the résumé of an academic failure. After a six-year stint at Yale in the ’90s that did not lead to a permanent job, he has bounced around from school to school, stringing together a series of short-term lectureships and temporary teaching positions in the United States, Europe and Israel. As of June, his curriculum vitae listed no publications to date — not even a journal article. At 60, he remains unknown to most scholars in his field.

Ever since completing his Ph.D. at the University of Pittsburgh in 1993, the Israeli philosopher Irad Kimhi has been building the résumé of an academic failure. After a six-year stint at Yale in the ’90s that did not lead to a permanent job, he has bounced around from school to school, stringing together a series of short-term lectureships and temporary teaching positions in the United States, Europe and Israel. As of June, his curriculum vitae listed no publications to date — not even a journal article. At 60, he remains unknown to most scholars in his field. Sigmund Freud, who referred to himself as a ‘godless Jew’, saw religion as delusional, but helpfully so. He argued that we humans are naturally awful creatures – aggressive, narcissistic wolves. Left to our own devices, we would rape, pillage and burn our way through life. Thankfully, we have the civilising influence of religion to steer us toward charity, compassion and cooperation by a system of carrots and sticks, otherwise known as heaven and hell.

Sigmund Freud, who referred to himself as a ‘godless Jew’, saw religion as delusional, but helpfully so. He argued that we humans are naturally awful creatures – aggressive, narcissistic wolves. Left to our own devices, we would rape, pillage and burn our way through life. Thankfully, we have the civilising influence of religion to steer us toward charity, compassion and cooperation by a system of carrots and sticks, otherwise known as heaven and hell.