Katy Waldman in The New Yorker:

Sally Horner was a widow’s daughter, a brown-haired honor student, from Camden, New Jersey. In 1948, hoping to impress some popular girls, she nicked a notebook from a dime store and was accosted by a man, Frank La Salle, posing as an F.B.I. agent. La Salle, who told Horner his name was Frank Warren, informed the eleven-year-old that he was placing her under surveillance. Then he commanded her to take a bus with him to Atlantic City, and from there they embarked on a cross-country road trip. Like Humbert Humbert, the protagonist of the novel “Lolita,” by Vladimir Nabokov, La Salle concealed his predations by posing as his victim’s father. (In the book, Humbert actually becomes Dolores Haze’s stepfather.) After enduring twenty-one months of rape and abuse, Sally finally opened up to a neighbor, Ruth Janisch, and found the strength to telephone her family back in Camden; the F.B.I. recovered her from a trailer park in Southern California and arrested La Salle, who confessed and went to prison for the rest of his life. In 1952, two years after her rescue, Sally was killed in a car crash.

Sally Horner was a widow’s daughter, a brown-haired honor student, from Camden, New Jersey. In 1948, hoping to impress some popular girls, she nicked a notebook from a dime store and was accosted by a man, Frank La Salle, posing as an F.B.I. agent. La Salle, who told Horner his name was Frank Warren, informed the eleven-year-old that he was placing her under surveillance. Then he commanded her to take a bus with him to Atlantic City, and from there they embarked on a cross-country road trip. Like Humbert Humbert, the protagonist of the novel “Lolita,” by Vladimir Nabokov, La Salle concealed his predations by posing as his victim’s father. (In the book, Humbert actually becomes Dolores Haze’s stepfather.) After enduring twenty-one months of rape and abuse, Sally finally opened up to a neighbor, Ruth Janisch, and found the strength to telephone her family back in Camden; the F.B.I. recovered her from a trailer park in Southern California and arrested La Salle, who confessed and went to prison for the rest of his life. In 1952, two years after her rescue, Sally was killed in a car crash.

“The Real Lolita” is Sarah Weinman’s attempt to pull back the veil on the kidnapping that may have helped inspire Nabokov’s novel.

More here.

In a report

In a report  It has been a year since Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico, leaving a trail of destruction: ruined infrastructure, destroyed homes, and thousands of fatalities. Since that particular hurricane has largely faded from the news, the slow rebuild continues and defining questions loom over the process: Who is Puerto Rico for? Outside investors and tourists or Puerto Ricans? After a collective trauma like Hurricane Maria, who has the right to decide for Puerto Rico? The fight for its future is underway.

It has been a year since Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico, leaving a trail of destruction: ruined infrastructure, destroyed homes, and thousands of fatalities. Since that particular hurricane has largely faded from the news, the slow rebuild continues and defining questions loom over the process: Who is Puerto Rico for? Outside investors and tourists or Puerto Ricans? After a collective trauma like Hurricane Maria, who has the right to decide for Puerto Rico? The fight for its future is underway. During the warm summer nights three years before Maidan, just as my Kyiv life began, I often stood where my grandma lived when her Kyiv life ended. Of all what drew to a close. Given everything that she told me, it seemed that those days were the happiest of her life: she was young and beautiful, she went on dates. ‘A few Jews were courting me’, she used to tell me proudly as if by way of feminine validation, as if to say, ‘Boy, I was hot!’ I’m not sure about the timeline. Maybe those happy years were directly after her father and brother came back from East Siberia in 1939; both had been arrested, tortured and imprisoned in a labour camp in 1937, but released two years later during the so called ‘Beria Amnesty’. She also witnessed the Great Famine (Holodomor) of 1932 and 1933, as well as the Babyn Yar massacre of 1941. I first learned of both tragedies from her, as they simply hadn’t featured in my Soviet school education. Those were the most terrifying years of Stalinist repression, yet she managed to find some joy in this city.

During the warm summer nights three years before Maidan, just as my Kyiv life began, I often stood where my grandma lived when her Kyiv life ended. Of all what drew to a close. Given everything that she told me, it seemed that those days were the happiest of her life: she was young and beautiful, she went on dates. ‘A few Jews were courting me’, she used to tell me proudly as if by way of feminine validation, as if to say, ‘Boy, I was hot!’ I’m not sure about the timeline. Maybe those happy years were directly after her father and brother came back from East Siberia in 1939; both had been arrested, tortured and imprisoned in a labour camp in 1937, but released two years later during the so called ‘Beria Amnesty’. She also witnessed the Great Famine (Holodomor) of 1932 and 1933, as well as the Babyn Yar massacre of 1941. I first learned of both tragedies from her, as they simply hadn’t featured in my Soviet school education. Those were the most terrifying years of Stalinist repression, yet she managed to find some joy in this city. Downes’s own meticulously descriptive pictures of the woebegone subjects that he favors—industrial zones, Texas deserts, highway structures, the New Jersey Meadowlands—do that, too, with a deadpan restraint that has kept his fan base small but ardent throughout the half century of his career. I’m a member. We cherish Downes’s evidence that painting can be truer than photography to the ways that our eyes process the world: reaping patches of tone and color which our brains combine very rapidly, but not instantly, into seamless wholes. He renders everything in his specialty of long, low panoramas, often encompassing more than a hundred and eighty degrees, which he always paints—on-site, over many sessions—head on, without either perspectival organization or fish-eye distortion. His avoidance of charm in his subjects and suppression of expressiveness in his touch serve the dumbfounded wonderment you can feel when—perhaps rarely enough, in this frantic era—you stop somewhere, look around, forget yourself, and only see. Downes’s is a puritanical passion, burning cold rather than hot but no less fiercely for that.

Downes’s own meticulously descriptive pictures of the woebegone subjects that he favors—industrial zones, Texas deserts, highway structures, the New Jersey Meadowlands—do that, too, with a deadpan restraint that has kept his fan base small but ardent throughout the half century of his career. I’m a member. We cherish Downes’s evidence that painting can be truer than photography to the ways that our eyes process the world: reaping patches of tone and color which our brains combine very rapidly, but not instantly, into seamless wholes. He renders everything in his specialty of long, low panoramas, often encompassing more than a hundred and eighty degrees, which he always paints—on-site, over many sessions—head on, without either perspectival organization or fish-eye distortion. His avoidance of charm in his subjects and suppression of expressiveness in his touch serve the dumbfounded wonderment you can feel when—perhaps rarely enough, in this frantic era—you stop somewhere, look around, forget yourself, and only see. Downes’s is a puritanical passion, burning cold rather than hot but no less fiercely for that. RAINDROP. IF THE MARK

RAINDROP. IF THE MARK Given the billions of dollars the world invests in science each year, it’s surprising how few researchers study science itself. But their number is growing rapidly, driven in part by the realization that science isn’t always the rigorous, objective search for knowledge it is supposed to be. Editors of medical journals, embarrassed by the quality of the papers they were publishing, began to turn the lens of science on their own profession decades ago, creating a new field now called “journalology.” More recently, psychologists have taken the lead, plagued by existential doubts after many results proved irreproducible. Other fields are following suit, and metaresearch, or research on research, is now blossoming as a scientific field of its own.

Given the billions of dollars the world invests in science each year, it’s surprising how few researchers study science itself. But their number is growing rapidly, driven in part by the realization that science isn’t always the rigorous, objective search for knowledge it is supposed to be. Editors of medical journals, embarrassed by the quality of the papers they were publishing, began to turn the lens of science on their own profession decades ago, creating a new field now called “journalology.” More recently, psychologists have taken the lead, plagued by existential doubts after many results proved irreproducible. Other fields are following suit, and metaresearch, or research on research, is now blossoming as a scientific field of its own. There is a longstanding debate among social scientists about what ultimately drives human behavior. Do ideals, symbols and beliefs lead people to act as they do? Or are the wellsprings of action and the drivers of history less ethereal: money, fear, the thirst for power, circumstance and opportunity, with culture as an afterthought?

There is a longstanding debate among social scientists about what ultimately drives human behavior. Do ideals, symbols and beliefs lead people to act as they do? Or are the wellsprings of action and the drivers of history less ethereal: money, fear, the thirst for power, circumstance and opportunity, with culture as an afterthought? About 40 years ago, Americans started getting much larger. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, nearly 80 percent of

About 40 years ago, Americans started getting much larger. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, nearly 80 percent of  As I write these words, I await Israel’s destruction of the only home and community that I have known in my 52 years of life. The 180 residents of my West Bank village,

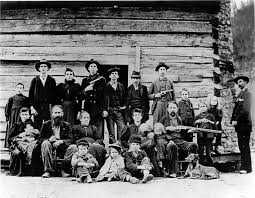

As I write these words, I await Israel’s destruction of the only home and community that I have known in my 52 years of life. The 180 residents of my West Bank village,  The so-called Hog Trial took place against a background of bitterness regarding Cline-McCoy loss of land in West Virginia. It’s hard not to recognize the hardships of the postwar decades in the mountains, particularly for the less affluent McCoys, for whom the butchering of a hog could mean the difference between eating or going hungry for some weeks. Fencing the steep land wasn’t practical, and livestock wandered between homesteads; farmers notched the ears of their animals as a form of branding. McCoy saw his notch on Floyd Hatfield’s hog and filed suit. Floyd, Anse’s cousin, lived on the Kentucky side of the river and was related to both families. Some say Randall McCoy’s actual motivation was anger that Floyd worked for Anse’s profitable timber operation. The local justice of the peace, “Preacher Anse” Hatfield, cousin to Devil Anse, impaneled a jury that was half Hatfield men, half McCoy men. McCoy juror Selkirk McCoy—son of Asa Harmon McCoy, the Union soldier murdered thirteen years before—worked, with two of his sons, among the thirty-five to forty men on the Hatfield timber crew. He apparently valued the present more than the past, and voted against Randall McCoy. No violence ensued, but the “betrayal” fueled resentment among the families. McCoy, a subsistence farmer and sometime ferryboat operator, was unable to provide economic stability or social or political status for his clan, while Hatfield’s success protected his family and employees from the economic decline endemic to the Tug Valley. The McCoy family was understandably frustrated, even furious, at the seemingly undefeated Hatfields.

The so-called Hog Trial took place against a background of bitterness regarding Cline-McCoy loss of land in West Virginia. It’s hard not to recognize the hardships of the postwar decades in the mountains, particularly for the less affluent McCoys, for whom the butchering of a hog could mean the difference between eating or going hungry for some weeks. Fencing the steep land wasn’t practical, and livestock wandered between homesteads; farmers notched the ears of their animals as a form of branding. McCoy saw his notch on Floyd Hatfield’s hog and filed suit. Floyd, Anse’s cousin, lived on the Kentucky side of the river and was related to both families. Some say Randall McCoy’s actual motivation was anger that Floyd worked for Anse’s profitable timber operation. The local justice of the peace, “Preacher Anse” Hatfield, cousin to Devil Anse, impaneled a jury that was half Hatfield men, half McCoy men. McCoy juror Selkirk McCoy—son of Asa Harmon McCoy, the Union soldier murdered thirteen years before—worked, with two of his sons, among the thirty-five to forty men on the Hatfield timber crew. He apparently valued the present more than the past, and voted against Randall McCoy. No violence ensued, but the “betrayal” fueled resentment among the families. McCoy, a subsistence farmer and sometime ferryboat operator, was unable to provide economic stability or social or political status for his clan, while Hatfield’s success protected his family and employees from the economic decline endemic to the Tug Valley. The McCoy family was understandably frustrated, even furious, at the seemingly undefeated Hatfields. In the conduct of public affairs in the 1530s, Cromwell seems ubiquitous and MacCulloch does more than any previous scholar (or even previous scholarship in aggregate) to track the range of his activities. There is a fascinating retelling of a familiar story: his role in dissolving monasteries. Cromwell was not, MacCulloch argues, ideologically wedded to complete appropriation of monastic assets; the Court of Augmentations – set up to handle the windfall, and the centrepiece of Elton’s ‘Tudor revolution’ – turns out not to have been his idea. Cromwell was, however, deeply concerned with the regulation of weirs and waterworks, a subject of possibly greater concern to some of the gentry. We learn of Cromwell’s adeptness in managing the governance of Wales, his much less sure hand (with future consequences) in attempting the same for Ireland and an apparent lack of interest in the affairs of Scotland. Another blind spot was the north of England, where Cromwell lacked connections and clientage: he was the target of vicious antipathy during the 1536–7 Pilgrimage of Grace.

In the conduct of public affairs in the 1530s, Cromwell seems ubiquitous and MacCulloch does more than any previous scholar (or even previous scholarship in aggregate) to track the range of his activities. There is a fascinating retelling of a familiar story: his role in dissolving monasteries. Cromwell was not, MacCulloch argues, ideologically wedded to complete appropriation of monastic assets; the Court of Augmentations – set up to handle the windfall, and the centrepiece of Elton’s ‘Tudor revolution’ – turns out not to have been his idea. Cromwell was, however, deeply concerned with the regulation of weirs and waterworks, a subject of possibly greater concern to some of the gentry. We learn of Cromwell’s adeptness in managing the governance of Wales, his much less sure hand (with future consequences) in attempting the same for Ireland and an apparent lack of interest in the affairs of Scotland. Another blind spot was the north of England, where Cromwell lacked connections and clientage: he was the target of vicious antipathy during the 1536–7 Pilgrimage of Grace. The emphasis on situation is one of the key factors that distinguishes Beauvoir from other existentialists. For Beauvoir, we are free, but we are also thrown into contexts where we don’t always have the freedom to choose. This is very different from Jean-Paul Sartre’s emphasis on radical freedom; by his lights, any attempt to blame our situation for our predicament is a denial of freedom – a form of bad faith. In Being and Nothingness, Sartre imagined an impassable crag – a “brute existent”, to use a Heideggerian term – and suggested that it’s only impassable if one had imagined that it would be possible to climb it. In a not-so-subtle attack on this idea, Beauvoir argues in Ethics of Ambiguity that, “If a door refuses to open, let us accept not opening it and there we are free. But by doing that, one manages only to save an abstract notion of freedom. It is emptied of all content and all truth”. Whereas for Sartre, “success is not important to freedom”, Beauvoir’s point is that without the possibility to act – if we’re limited by our situation – then freedom is rendered impotent. We may be free to scale a crag, but unless we have the power to do it, it means nothing.

The emphasis on situation is one of the key factors that distinguishes Beauvoir from other existentialists. For Beauvoir, we are free, but we are also thrown into contexts where we don’t always have the freedom to choose. This is very different from Jean-Paul Sartre’s emphasis on radical freedom; by his lights, any attempt to blame our situation for our predicament is a denial of freedom – a form of bad faith. In Being and Nothingness, Sartre imagined an impassable crag – a “brute existent”, to use a Heideggerian term – and suggested that it’s only impassable if one had imagined that it would be possible to climb it. In a not-so-subtle attack on this idea, Beauvoir argues in Ethics of Ambiguity that, “If a door refuses to open, let us accept not opening it and there we are free. But by doing that, one manages only to save an abstract notion of freedom. It is emptied of all content and all truth”. Whereas for Sartre, “success is not important to freedom”, Beauvoir’s point is that without the possibility to act – if we’re limited by our situation – then freedom is rendered impotent. We may be free to scale a crag, but unless we have the power to do it, it means nothing. Until recent years, the sound of rain has always filled me with a sense of blessing. Rain drumming on the tin roof of a Tennessee farmhouse, my first home. Rain pattering on the canopy of oak and maple forests in Ohio, on forests of pine in Maine and Vermont, on reeds and rushes in Louisiana bayous, on spongy nurse logs in Oregon, on tundra and stone in Alaska. From earliest childhood, I would tingle with anticipation at the rumble of an oncoming storm. I would shiver with pleasure as rain tapped on windows and gurgled through gutters, and I would dash outside to rejoice in the thrum of rain on my umbrella or on the hood of my slicker. I heard in these sounds a promise of green grass, sweet corn, flowing creeks. It was the music of abundance. When preachers in the rural Methodist churches I attended as a boy spoke of grace, I thought of rain.

Until recent years, the sound of rain has always filled me with a sense of blessing. Rain drumming on the tin roof of a Tennessee farmhouse, my first home. Rain pattering on the canopy of oak and maple forests in Ohio, on forests of pine in Maine and Vermont, on reeds and rushes in Louisiana bayous, on spongy nurse logs in Oregon, on tundra and stone in Alaska. From earliest childhood, I would tingle with anticipation at the rumble of an oncoming storm. I would shiver with pleasure as rain tapped on windows and gurgled through gutters, and I would dash outside to rejoice in the thrum of rain on my umbrella or on the hood of my slicker. I heard in these sounds a promise of green grass, sweet corn, flowing creeks. It was the music of abundance. When preachers in the rural Methodist churches I attended as a boy spoke of grace, I thought of rain. The science-fiction writer Robert Heinlein once wrote, “Each generation thinks it invented sex.” He was presumably referring to the pride each generation takes in defining its own sexual practices and ethics. But his comment hit the mark in another sense: Every generation has to reinvent sex because the previous generation did a lousy job of teaching it. In the United States, the conversations we have with our children about sex are often awkward, limited, and brimming with euphemism. At school, if kids are lucky enough to live in a state that allows it, they’ll get something like 10 total hours of sex education.1 If they’re less lucky, they’ll instead experience the curious phenomenon of abstinence-only education, in which the goal is to avoid transmitting any information at all. In addition to being counterproductive—potentially leading to higher rates of teen pregnancy2 and sexually transmitted illnesses3—this practice is strange. Compare it to the practices of many small-scale societies, where children first learn about sex by observing their parents!

The science-fiction writer Robert Heinlein once wrote, “Each generation thinks it invented sex.” He was presumably referring to the pride each generation takes in defining its own sexual practices and ethics. But his comment hit the mark in another sense: Every generation has to reinvent sex because the previous generation did a lousy job of teaching it. In the United States, the conversations we have with our children about sex are often awkward, limited, and brimming with euphemism. At school, if kids are lucky enough to live in a state that allows it, they’ll get something like 10 total hours of sex education.1 If they’re less lucky, they’ll instead experience the curious phenomenon of abstinence-only education, in which the goal is to avoid transmitting any information at all. In addition to being counterproductive—potentially leading to higher rates of teen pregnancy2 and sexually transmitted illnesses3—this practice is strange. Compare it to the practices of many small-scale societies, where children first learn about sex by observing their parents! The dubious notion

The dubious notion