Molly Young in the New York Times:

A thought experiment: If hangovers didn’t exist, what percentage of your life would you spend drunk? It’s unexpectedly hard to predict. Part of the thrill of getting wasted, after all, is knowing that you’re sacrificing your future self for your present self’s fun. That’s the point of bad behavior.

A thought experiment: If hangovers didn’t exist, what percentage of your life would you spend drunk? It’s unexpectedly hard to predict. Part of the thrill of getting wasted, after all, is knowing that you’re sacrificing your future self for your present self’s fun. That’s the point of bad behavior.

The Canadian writer and actor Shaughnessy Bishop-Stall is a fine person to write a book about hangovers, not only because he’s a tenacious researcher but also because he’s willing to get thoroughly torn up on a consistent basis in colorful circumstances. He gorges on single-malt Scotch in Las Vegas, swallows a dozen pints of ale in a series of English pubs, binges on tequila and collapses beside a cactus near the Mexican border, wears lederhosen to a German beer festival and so forth. Reading his chronicle, “Hungover: The Morning After and One Man’s Quest for the Cure,” has an effect not unlike recovering from food poisoning or slipping into a warm house on a frigid night. You turn the pages thinking, “Thank God I don’t feel like that right now.” Or maybe, “Thank God I’m not this guy.”

According to Bishop-Stall, a hangover is composed of two forces combining to form a third force of great evil, like warm water and a storm cluster smashing together into a hurricane. One of the forces is dehydration. Alcohol is a diuretic, which is the reason the bathroom lines in bars are so long and why you wake up from a binge gasping for water. The second force is fatigue. Although alcohol sedates you, it won’t permit access to the deepest levels of sleep, which is why you can pass out for hours and still wake up feeling (and physiologically being) exhausted.

More here.

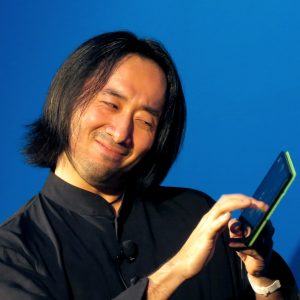

Everywhere around us are things that serve functions. We live in houses, sit on chairs, drive in cars. But these things don’t only serve functions, they also come in particular forms, which may be emotionally or aesthetically pleasing as well as functional. The study of how form and function come together in things is what we call “Design.” Today’s guest, Ge Wang, is a computer scientist and electronic musician with a new book called Artful Design: Technology in Search of the Sublime. It’s incredibly creative in both substance and style, featuring a unique photo-comic layout and many thoughtful ideas about the nature of design, both practical and idealistic. We talk about what design is, how it can be artful, and in what sense it points us toward the sublime.

Everywhere around us are things that serve functions. We live in houses, sit on chairs, drive in cars. But these things don’t only serve functions, they also come in particular forms, which may be emotionally or aesthetically pleasing as well as functional. The study of how form and function come together in things is what we call “Design.” Today’s guest, Ge Wang, is a computer scientist and electronic musician with a new book called Artful Design: Technology in Search of the Sublime. It’s incredibly creative in both substance and style, featuring a unique photo-comic layout and many thoughtful ideas about the nature of design, both practical and idealistic. We talk about what design is, how it can be artful, and in what sense it points us toward the sublime. If there were a tagline for today’s populist moment, it would probably be something like “It’s not the economy, stupid.” Economic factors matter, but they are far from decisive in understanding why populists, especially right-wing populists, have solidified their position as the second largest or even largest parties in many Western democracies.

If there were a tagline for today’s populist moment, it would probably be something like “It’s not the economy, stupid.” Economic factors matter, but they are far from decisive in understanding why populists, especially right-wing populists, have solidified their position as the second largest or even largest parties in many Western democracies. W

W Cézanne’s kind of painting—the digital kind, composed of discrete marks—is so far removed from the analog illusions of photography that its engagement with cultural issues is of a divergent sort. By rendering its technique explicit, it revealed its liaison with living sensation, eye-to-hand. Artist-theorist André Lhote wrote in 1920: “A large part of the emotive power of Cézanne’s canvases derives from the fact that the painter, rather than hide them, shows his means.”

Cézanne’s kind of painting—the digital kind, composed of discrete marks—is so far removed from the analog illusions of photography that its engagement with cultural issues is of a divergent sort. By rendering its technique explicit, it revealed its liaison with living sensation, eye-to-hand. Artist-theorist André Lhote wrote in 1920: “A large part of the emotive power of Cézanne’s canvases derives from the fact that the painter, rather than hide them, shows his means.” On a recent afternoon, Ivan Novak, a member of the Slovenian rock group Laibach, went for a walk in the hills overlooking the country’s capital, Ljubljana. In between stops to pet passing dogs, he explained what it was like when Laibach became the first Western band to perform in North Korea.

On a recent afternoon, Ivan Novak, a member of the Slovenian rock group Laibach, went for a walk in the hills overlooking the country’s capital, Ljubljana. In between stops to pet passing dogs, he explained what it was like when Laibach became the first Western band to perform in North Korea. It says something about Lin-Manuel Miranda’s genius that he even managed to make fiscal integration catchy. In his musical Hamilton, the eponymous treasury secretary raps:

It says something about Lin-Manuel Miranda’s genius that he even managed to make fiscal integration catchy. In his musical Hamilton, the eponymous treasury secretary raps: You’d think that scientists at an international conference on obesity would know by now which diet is best, and why. As it turns out, even the experts still have widely divergent opinions. At a recent meeting of the Obesity Society, organizers held a

You’d think that scientists at an international conference on obesity would know by now which diet is best, and why. As it turns out, even the experts still have widely divergent opinions. At a recent meeting of the Obesity Society, organizers held a  The day before Thanksgiving I got this wonderfully understated text from a close friend:

The day before Thanksgiving I got this wonderfully understated text from a close friend:

Our uniform was a shirt tucked into jeans. Sandi stretched the smallest size over well-proportioned breasts, her black bra peeking through a run of buttons. Mine hung long in the sleeves and fell over my waist.

Our uniform was a shirt tucked into jeans. Sandi stretched the smallest size over well-proportioned breasts, her black bra peeking through a run of buttons. Mine hung long in the sleeves and fell over my waist.

In the middle of the night of March 24, 1992, a pressure seal failed in the number three unit of the Leningradskaya Nuclear Power Plant at Sosnoviy Bor, Russia, releasing radioactive gases. With a friend, I had train tickets from Tallinn, in newly independent Estonia, to St. Petersburg the next day. That would take us within twenty kilometers of the plant. The legacy of Soviet management at Chernobyl a few years before set up a fraught decision whether or not to take the train.

In the middle of the night of March 24, 1992, a pressure seal failed in the number three unit of the Leningradskaya Nuclear Power Plant at Sosnoviy Bor, Russia, releasing radioactive gases. With a friend, I had train tickets from Tallinn, in newly independent Estonia, to St. Petersburg the next day. That would take us within twenty kilometers of the plant. The legacy of Soviet management at Chernobyl a few years before set up a fraught decision whether or not to take the train. Noam Chomsky was aptly described in a New York Times book review published almost four decades ago as “arguably the most important intellectual alive today.” He was 50 then. Now he is 90, and on the occasion of his December 7 birthday, the German international broadcasting service Deutsche Welle

Noam Chomsky was aptly described in a New York Times book review published almost four decades ago as “arguably the most important intellectual alive today.” He was 50 then. Now he is 90, and on the occasion of his December 7 birthday, the German international broadcasting service Deutsche Welle  In the spring of 2015, with my colleagues at the Breakthrough Institute, I helped to organize and publish

In the spring of 2015, with my colleagues at the Breakthrough Institute, I helped to organize and publish  Ivan Krastev’s last book landed like a warning shot on the desks of policymakers across the Continent. In his short 2017 volume, “After Europe,” the Bulgarian thinker warned that what had been until then widely regarded as a series of isolated shocks — the migration crisis, Brexit, the election of U.S. President Donald Trump, and the rise of

Ivan Krastev’s last book landed like a warning shot on the desks of policymakers across the Continent. In his short 2017 volume, “After Europe,” the Bulgarian thinker warned that what had been until then widely regarded as a series of isolated shocks — the migration crisis, Brexit, the election of U.S. President Donald Trump, and the rise of