Category: Recommended Reading

These Portraits Were Made by AI: None of These People Exist

Michael Zhang in Peta Pixel:

Check out these rather ordinary looking portraits. They’re all fake. Not in the sense that they were Photoshopped, but rather they were completely generated by artificial intelligence. That’s right: none of these people actually exist.

More here.

Time to Log Off

Ian Marcus Corbin at The New Atlantis:

It goes without saying — everyone knows it now, even if they can’t say why — that things like social media are bad for us, that many of us are clinically addicted to our phones, that life online brings out the worst in many, and probably in most of us. Twitter has damaged our national discourse, infecting it with a hair-triggered, toxic factionalism. The news is familiar enough — someone says something, Twitter erupts with outrage; details to follow. This is news. We treat all this with a knowing grimace, and write wry little tweets about how Twitter is toxic. We admire the founders of websites and apps that make us miserable, and if we are ambitious entrepreneurial types, aspire to be like them.

It goes without saying — everyone knows it now, even if they can’t say why — that things like social media are bad for us, that many of us are clinically addicted to our phones, that life online brings out the worst in many, and probably in most of us. Twitter has damaged our national discourse, infecting it with a hair-triggered, toxic factionalism. The news is familiar enough — someone says something, Twitter erupts with outrage; details to follow. This is news. We treat all this with a knowing grimace, and write wry little tweets about how Twitter is toxic. We admire the founders of websites and apps that make us miserable, and if we are ambitious entrepreneurial types, aspire to be like them.

Fine, the zeitgeist moves at its glacial pace, until it decides it’s time to move quickly. Humans are weak and will sate their thirst with the nearest liquid, at least for a time. There is reason to think, though, that this digital world will die, or at least radically morph, as its ill effects come further into view. Technology, and especially social media use — this gigantic monument of our collective creation — will begin to be treated as a public health issue within a decade, I predict. The studies are piling up, no moral argument today is so dispositive.

more here.

Learn While You Sleep (Hypnopaedia)

B. Alexandra Szerlip at The Believer:

Hypnopaedia aka Sleep Learning had been thrust upon the public in 1921, courtesy of a Science and Invention Magazine cover story. Echoing Poe, Hugo Gernsback informed his readers that sleep “is only another form of death,” but our subconscious “is always on the alert.” If we could “superimpose” learning on our sleeping senses, would it not be “an inestimable boon to humanity?” Would it not “lift the entire human race to a truly unimaginable extent?”

Hypnopaedia aka Sleep Learning had been thrust upon the public in 1921, courtesy of a Science and Invention Magazine cover story. Echoing Poe, Hugo Gernsback informed his readers that sleep “is only another form of death,” but our subconscious “is always on the alert.” If we could “superimpose” learning on our sleeping senses, would it not be “an inestimable boon to humanity?” Would it not “lift the entire human race to a truly unimaginable extent?”

Gernsback proposed that talking machines, operating on the Poulsen Telegraphone Principle (magnetic recordings on steel wires) be installed in people’s bedrooms. The recordings library would be housed in a large central exchange; subscribers could place their orders by radiophone. Then, between midnight and 6 a.m., requests would be “flashed out,” over those same radiophones, onto reels, each with enough wire to last for an hour of continuous service. Eight reels would give the sleeper enough material for a whole nights’ work!

In other words, in 1921 he anticipated the first spoken word LPs (Caedmon Records, est. 1952), Books of Tape (est. 1975) and the first digitally downloaded audio books (mid-1990s).

more here.

Walton Ford: Twenty-First-Century Naturalist

Lucy Jakub at the NYRB:

Looking at the paintings of Walton Ford in a book, you might mistake them for the watercolors of a nineteenth-century naturalist: they are annotated in longhand script, and yellowed at the edges as if stained by time and voyage. Something’s always outrageously off, though: the gorilla is holding a human skull; a couple of parrots are mating on the shaft of an elephant’s penis. In his early riffs on Audubon prints, Ford painted birds mid-slaughter: his American Flamingo (1992) flails head over heels after being shot with a rifle, and an eagle with its foot in a trap billows smoke from its beak (Audubon, in search of a painless method of execution, tried unsuccessfully to asphyxiate an eagle with sulfurous gas).

Looking at the paintings of Walton Ford in a book, you might mistake them for the watercolors of a nineteenth-century naturalist: they are annotated in longhand script, and yellowed at the edges as if stained by time and voyage. Something’s always outrageously off, though: the gorilla is holding a human skull; a couple of parrots are mating on the shaft of an elephant’s penis. In his early riffs on Audubon prints, Ford painted birds mid-slaughter: his American Flamingo (1992) flails head over heels after being shot with a rifle, and an eagle with its foot in a trap billows smoke from its beak (Audubon, in search of a painless method of execution, tried unsuccessfully to asphyxiate an eagle with sulfurous gas).

Ford is never interested merely in the natural world, but in the way humans have documented, exploited, and repurposed it, and how these species have been mythologized, even as most of them have disappeared from the wild. Walton Ford makes paintings of paintings of animals.

more here.

Wednesday Poem

Adulthood

……….. —for claudia

i usta wonder who I’d be

when i was a little girl in Indianapolis

sitting on doctors porches with post-dawn pre-debs

(wondering would my aunt drag me to church Sunday)

i was meaningless

and I wondered if life

would give me a chance to mean

i found a new life in the withdrawal from all things

not like my image

when I was a teenager I usta sit

on front steps conversing

the gym teachers son with embryonic eyes

about the essential essence of the universe

(and other bullshit stuff)

recognizing the basic powerlessness of me

but then i went to college where I learned

that just because everything I was was unreal

that i could be real and not just real through withdrawal

into emotional crosshairs or colored bourgeoisie intellectual pretentions

but from involvement with things approaching reality

i could possible have a life

so catatonic emotions and time wasting sex games

were replaced with functioning commitments to logic and

necessity and the gray area was slowly darkened into

a black thing

for a while progress was being made along with a certain degree

of happiness cause I wrote a book and found a love

and organized a theater and even gave some lectures on

Black history

and began to believe all good people could get

together and win without bloodshed

then

Read more »

On a bat’s wing and a prayer

Lena H. Sun in The Washington Post:

By day, some of the most dangerous animals in the world lurk deep inside this cave. Come night, the tiny fruit bats whoosh out, tens of thousands of them at a time, filling the air with their high-pitched chirping before disappearing into the black sky. The bats carry the deadly Marburg virus, as fearsome and mysterious as its cousin Ebola. Scientists know that the virus starts in these animals, and they know that when it spreads to humans it is lethal — Marburg kills up to 9 in 10 of its victims, sometimes within a week. But they don’t know much about what happens in between. That’s where the bats come Prevention traveled here to track their movements in the hopes that spying on their nightly escapades could help prevent the spread of one of the world’s most dreaded diseases. Because there is a close relationship between Marburg and Ebola, the scientists are also hopeful that progress on one virus could help solve the puzzle of the other.

By day, some of the most dangerous animals in the world lurk deep inside this cave. Come night, the tiny fruit bats whoosh out, tens of thousands of them at a time, filling the air with their high-pitched chirping before disappearing into the black sky. The bats carry the deadly Marburg virus, as fearsome and mysterious as its cousin Ebola. Scientists know that the virus starts in these animals, and they know that when it spreads to humans it is lethal — Marburg kills up to 9 in 10 of its victims, sometimes within a week. But they don’t know much about what happens in between. That’s where the bats come Prevention traveled here to track their movements in the hopes that spying on their nightly escapades could help prevent the spread of one of the world’s most dreaded diseases. Because there is a close relationship between Marburg and Ebola, the scientists are also hopeful that progress on one virus could help solve the puzzle of the other.

Their task is to glue tiny GPS trackers on the backs of 20 bats so they can follow their movements.

…Well before you see the bats — about 50,000 live in the cave — you hear their squeaks and chatter and smell the ammonia from their guano, which also covers the cave’s rocky floor. One false step can lead to a fall into a stream underneath. Another could land the scientists on one of the African rock pythons or forest cobras that slither along the ground.

More here.

Tuesday, December 18, 2018

Aristophanes’ Orphans: A Disabled Trans Woman Surveys the Grey Zone Between Love and Fetish

Emma McAllister in Quillette:

Since I first read Plato’s Symposium, I have been fond of Aristophanes’ account of the origin of love. The tale goes something like this. Human beings used to be spherical creatures with four legs, four arms, and two faces divided evenly between each side. We also used to come in three distinct varieties. Men were those composed of two male halves, women were those composed of two female halves, and the androgynous were those composed of both a male and a female half.

Since I first read Plato’s Symposium, I have been fond of Aristophanes’ account of the origin of love. The tale goes something like this. Human beings used to be spherical creatures with four legs, four arms, and two faces divided evenly between each side. We also used to come in three distinct varieties. Men were those composed of two male halves, women were those composed of two female halves, and the androgynous were those composed of both a male and a female half.

Everything was going swell for us, you might say, until the gods meddled, as they were wont to do. Fearing the power of humanity, Zeus sliced every human into two and had Apollo sew up the opening, with our belly buttons serving as a reminder not to test the power of the gods. Everyone found themselves feeling empty and longing for their other half, be it the woman you were attached to or the man you were attached to. Love was born out of the search to be whole.

I’m fond of this narrative for its simple beauty. But it is sadly incomplete. As progressives are quick to note, sexual attraction is more complicated than the pairings of men and women. People come in all sorts of shapes and sizes. And some categories of human are so peculiar that they can confound the very notion of healthy sexual attraction. In such cases, we sometimes use the term “fetish” to suggest that there is something odd, or even unwholesome, at play.

More here.

Radical differences in the humanities and sciences haven’t gone away — they’ve intensified

Steven Klein in the Chronicle of Higher Education:

The relationship between the humanities and the sciences, including some quarters of the social sciences, has become strained, to put it mildly. Developments in cognitive neuroscience and other fields — from sophisticated brain-imaging techniques to increasingly detailed knowledge of human genetics — promise to revolutionize our knowledge of human behavior. And these changes have propelled a new, more hard-edged round in the science wars. In 2002, Steven Pinker, in his best-selling The Blank Slate, chastised the humanities for presenting culture as a malleable product of human will. While the first science wars, fought in the 1990s, focused on broad questions regarding the basis of scientific knowledge, today science warriors accuse the humanities of ignoring human nature, and especially natural human differences.

The relationship between the humanities and the sciences, including some quarters of the social sciences, has become strained, to put it mildly. Developments in cognitive neuroscience and other fields — from sophisticated brain-imaging techniques to increasingly detailed knowledge of human genetics — promise to revolutionize our knowledge of human behavior. And these changes have propelled a new, more hard-edged round in the science wars. In 2002, Steven Pinker, in his best-selling The Blank Slate, chastised the humanities for presenting culture as a malleable product of human will. While the first science wars, fought in the 1990s, focused on broad questions regarding the basis of scientific knowledge, today science warriors accuse the humanities of ignoring human nature, and especially natural human differences.

These controversies could potentially illuminate core moral and political questions about the nature of scholarship, humanistic and otherwise. Yet, as with so many dysfunctional relationships, partisans of each side think they are having a conversation without really talking to each other at all. Take the dust-up that began when Slate’s chief political correspondent, Jamelle Bouie, wrote about the historical connection between race and the philosophy of the Enlightenment. Bouie was responding to recent critics of the humanities, most notably Pinker, whose Enlightenment Now provides a rousing call for us to use science to improve the human condition. Against Pinker’s idea of the Enlightenment as a model for rational problem-solving today, Bouie pointed out that many Enlightenment thinkers, such as Immanuel Kant, helped forge modern notions of racial classification and hierarchy. It’s not so simple a task, then, to just draw on the Enlightenment ideal of rational progress. We must also, Bouie argued, confront Enlightenment ideals’ continued entanglement with racism and European imperial ideology.

More here.

Can the Working Class Speak?

Maximillian Alvarez in Current Affairs:

I regret never really getting to know my dad until after the world broke him. And it’s not like I didn’t know him well before—I did. But not in the way I know him now. I wish I had known him better before everything went to hell, before the Recession hit, before we lost just about everything, so that he didn’t have to go through it all feeling like I didn’t, and couldn’t, know what he was going through. To be perfectly honest, though, I don’t think he really knew either.

I regret never really getting to know my dad until after the world broke him. And it’s not like I didn’t know him well before—I did. But not in the way I know him now. I wish I had known him better before everything went to hell, before the Recession hit, before we lost just about everything, so that he didn’t have to go through it all feeling like I didn’t, and couldn’t, know what he was going through. To be perfectly honest, though, I don’t think he really knew either.

Pops was never that much of a chatterbox. So, we all had to learn how to mine his brief words for hidden meaning. My siblings and I could decipher in a quick, throwaway suggestion that we watch a certain movie with him sometime a clear message that he really wanted to watch it with us now. We could discern many fine layers of disappointment in the way he said “Mmm …” We could read his laughs like practiced fortune-tellers reading tea-leaves. And then there were his silences: The angry silence was obvious and terrifying; the smirking silence usually meant that he was still laughing inside at his own joke; the pensive silences when certain songs were playing usually corresponded to memories we had heard about enough times that we could practically see them playing out in his head.

But then, around Christmas, something changes. I see my dad sitting like a shadow. The familiar emotional cues I had once known how to read now seem lost in static, shershing and flashing on a channel we don’t get, faint, ghostly shapes swimming somewhere under the surface. Suddenly, my dad has become illegible.

It’s clear that Christmas that my parents are hiding something from us.

More here.

Hans and Ola Rosling: How not to be ignorant about the world

Sylvia Plath at 86

Joanna Biggs at the LRB:

Plath grows up in Cold War America, deceived by a God who let her father die, wanting more than anything to be a writer and to marry a man who would make her feel like she had a vodka sword in her stomach, always. And she gets it when she arrives in Cambridge in 1956, meets her black marauder and marries him ‘in mother’s gift of a pink knit dress’ three and a half months later. (When I got married at 28 to the man I met at Oxford at 19, I married in pink partly under the influence of Ted and Sylvia, partly because my mother had also married, though not knowing or caring about Plath, in a pink knitted dress in 1977. I liked the resonances, then.) But the world, even when it gives her what she wants, also doesn’t. Literary success is baseless, fleeting; the marriage dissolves in betrayal, arguments, abandonment. The hard work has come to ash. Awake at 4 a.m. when the sleeping pills wear off, she finds a voice and writes the poems of her life, ones that will make her a myth like Lazarus, like Lorelei. But now she knows that her conception of her life, psychological and otherwise, is no longer tenable, and never was. Now what? ‘I love you for listening,’ Plath, abandoned and alone, tells her analyst Ruth Beuscher in a letter late in 1962. The rest of us are listening at last.

Plath grows up in Cold War America, deceived by a God who let her father die, wanting more than anything to be a writer and to marry a man who would make her feel like she had a vodka sword in her stomach, always. And she gets it when she arrives in Cambridge in 1956, meets her black marauder and marries him ‘in mother’s gift of a pink knit dress’ three and a half months later. (When I got married at 28 to the man I met at Oxford at 19, I married in pink partly under the influence of Ted and Sylvia, partly because my mother had also married, though not knowing or caring about Plath, in a pink knitted dress in 1977. I liked the resonances, then.) But the world, even when it gives her what she wants, also doesn’t. Literary success is baseless, fleeting; the marriage dissolves in betrayal, arguments, abandonment. The hard work has come to ash. Awake at 4 a.m. when the sleeping pills wear off, she finds a voice and writes the poems of her life, ones that will make her a myth like Lazarus, like Lorelei. But now she knows that her conception of her life, psychological and otherwise, is no longer tenable, and never was. Now what? ‘I love you for listening,’ Plath, abandoned and alone, tells her analyst Ruth Beuscher in a letter late in 1962. The rest of us are listening at last.

more here.

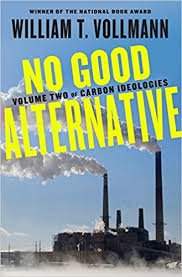

William T. Vollmann Confronts Climate Change

Katy Lederer at n+1:

Like all honest ethnographies, Carbon Ideologies also functions as an intellectual autobiography. We learn that, during his six years of research, Vollmann depleted his original advance and then spent his own money and unnamed others’ to “hike up strip-mined mountains, sniff crude oil, and occasionally tan my face with gamma rays.” (He relegates renewables to just a few pages, largely dismissing them, as he explicitly does solar, as “an ideology of hope—not my department.”) He loves gadgets and toys. In the first volume, this love expresses itself mainly in the form of an unmistakably phallic pancake frisker he carries around Fukushima, which he uses to measure the radioactivity of everything from roadside vegetation to the ubiquitous black bags of nuclear waste that line the empty streets. Dozens of pictures serve to document his travels. In one we see Vollmann’s hand grasping the frisker at the neck, pointing it at a bald statue of a praying man at a temple called Hen Jo.

Like all honest ethnographies, Carbon Ideologies also functions as an intellectual autobiography. We learn that, during his six years of research, Vollmann depleted his original advance and then spent his own money and unnamed others’ to “hike up strip-mined mountains, sniff crude oil, and occasionally tan my face with gamma rays.” (He relegates renewables to just a few pages, largely dismissing them, as he explicitly does solar, as “an ideology of hope—not my department.”) He loves gadgets and toys. In the first volume, this love expresses itself mainly in the form of an unmistakably phallic pancake frisker he carries around Fukushima, which he uses to measure the radioactivity of everything from roadside vegetation to the ubiquitous black bags of nuclear waste that line the empty streets. Dozens of pictures serve to document his travels. In one we see Vollmann’s hand grasping the frisker at the neck, pointing it at a bald statue of a praying man at a temple called Hen Jo.

more here.

Kafka’s Last Trial

Kevin Jackson at Literary Review:

The question of who owns Kafka is at the heart of Benjamin Balint’s thought-provoking and assiduously researched Kafka’s Last Trial, which (to simplify) is about the attempt by the state of Israel to prevent the sale of Kafka’s manuscripts from a private collection there to anywhere overseas, particularly to the German Literature Archive in Marbach. Spoiler alert for those who were not reading the newspapers in 2016: the state won. But Balint’s book is not so much about the outcome as it is about the arguments that were brought forward.

The question of who owns Kafka is at the heart of Benjamin Balint’s thought-provoking and assiduously researched Kafka’s Last Trial, which (to simplify) is about the attempt by the state of Israel to prevent the sale of Kafka’s manuscripts from a private collection there to anywhere overseas, particularly to the German Literature Archive in Marbach. Spoiler alert for those who were not reading the newspapers in 2016: the state won. But Balint’s book is not so much about the outcome as it is about the arguments that were brought forward.

The reason Kafka’s papers ended up in Israel is simple: Brod, a Zionist, brought them there. After Brod’s death, in 1968, the archive passed to his secretary and confidante Esther Hoffe. She died in 2007 at the age of 101, leaving the papers to her daughters Eva and Ruth; Ruth died not long afterwards, leaving Eva Hoffe as the owner of the cache, which was of considerable size.

more here.

Tuesday Poem

The Belly Dancer

Across the road the decorators have finished;

your flat has net curtains again

after all these weeks, and a ‘To Let’ sign.

I can only think of it as a tomb,

excavated, in the end, by

explorers in facemasks and protective spacesuits.

No papers, no bank account, no next of kin;

only a barricade against the landlord,

and the police at our doors, early, with questions.

What did we know? Not much: a Lebanese name,

a soft English voice; chats in the street

in your confiding phase; the dancing.

You sat behind me once at midnight Mass.

You were Orthodox, really; church

made you think of your mother, and cry.

From belly dancer to recluse, the years

and the stealthy ballooning of your outline,

kilo by kilo, abducted you.

Poor girl, I keep saying; poor girl –

no girl, but young enough to be my daughter.

I called at your building once, canvassing;

your face loomed in the hallway and, forgetting

whether or not we were social kissers,

I bounced my lips on it. It seemed we were not.

They’ve even replaced your window frames. I still

imagine a midden of flesh, and that smell

you read about in reports of earthquakes.

They say there was a heart beside your doorbell

upstairs. They say all sorts. They would –

who’s to argue? I don’t regret the kiss.

by Fleur Adcock

from Glass Wings

publisher: Bloodaxe, Newcastle, 2013

The amateur scientists tackling the global energy crisis

Will Dunn in New Statesman:

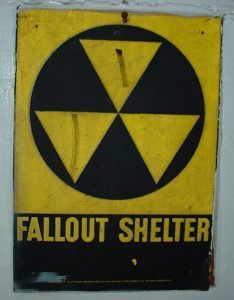

For his eighth birthday, Richard Hull’s mother bought him a Geiger counter. It was 1955 and the United States was testing nuclear weapons on its own soil. “They would always announce a test in the newspaper,” Hull remembers. “The material that went into the stratosphere drifted with the prevailing winds. The radioactive fallout particles came down with rain, as far north as New York and as far south as Georgia.” Hull lived then, as now, in Virginia, squarely in the path of the fallout that blew east from the bombs in the Nevada desert. “We would have days when we couldn’t have milk,” he remembers, “because of the strontium-90.” Hull wanted a Geiger counter not because he was afraid of radioactivity, but because he was enthralled by it. He pointed his new toy at anything that might make it tick, from wristwatches to rocks, and he collected fallout from the bombs. “I would take bird-bath water, or water that I gathered in pails from the downspouts of the house, and I would slowly evaporate that water on my mother’s stove, and that would leave the solids behind. And they were highly radioactive,” he says, with evident satisfaction.

For his eighth birthday, Richard Hull’s mother bought him a Geiger counter. It was 1955 and the United States was testing nuclear weapons on its own soil. “They would always announce a test in the newspaper,” Hull remembers. “The material that went into the stratosphere drifted with the prevailing winds. The radioactive fallout particles came down with rain, as far north as New York and as far south as Georgia.” Hull lived then, as now, in Virginia, squarely in the path of the fallout that blew east from the bombs in the Nevada desert. “We would have days when we couldn’t have milk,” he remembers, “because of the strontium-90.” Hull wanted a Geiger counter not because he was afraid of radioactivity, but because he was enthralled by it. He pointed his new toy at anything that might make it tick, from wristwatches to rocks, and he collected fallout from the bombs. “I would take bird-bath water, or water that I gathered in pails from the downspouts of the house, and I would slowly evaporate that water on my mother’s stove, and that would leave the solids behind. And they were highly radioactive,” he says, with evident satisfaction.

For Hull and others like him, radioactivity is not a poison but a thrill, a kind of life within materials. The uranium we find on Earth, he explains, has been ticking away since before the planet itself was formed. “It has been decaying since the supernova that blew the material off and [it] slowly accreted into the Earth, billions of years ago. And it’s still going today. That fascinated me,” he says. “It still does.” This fascination has led Hull to experiment with radioactivity for more than 60 years. Under Eisenhower’s educational “Atoms for Peace” programme, a schoolchild in the 1950s could order small quantities of radio isotopes to their home, so Hull wrote to the US nuclear facilities for free samples of caesium-137, sulphur-42 and cobalt-60. Following a guide in Scientific American, he contaminated clover plants with radio-phosphorus and laid them on photographic paper, creating radiographic pictures of the veins within the leaves.

More here.

A Very Personal Problem

Dina Fine Maron in Scientific American:

Doctors are not accustomed to making medication choices using genetics. What they have done, for decades, is to look at easily observed factors such as a patient’s age and weight and kidney or liver functions. They also considered what other medications a patient is taking and any personal preferences. If clinicians would consider genetics, here is what they could learn about prescribing the common painkiller codeine. Typically the body produces an enzyme called CYP2D6 that breaks down the drug into its active ingredient, morphine, which provides pain relief. Yet as many as 10 percent of patients have genetic variants that produce too little of the enzyme, so almost no codeine gets turned into morphine. These people get little or no help for their pain. About 2 percent of the population has the reverse problem. They have too many copies of the gene that produces the enzyme, leading to overproduction. For them, a little codeine can quickly turn into too much morphine, which can lead to a fatal overdose.

Doctors are not accustomed to making medication choices using genetics. What they have done, for decades, is to look at easily observed factors such as a patient’s age and weight and kidney or liver functions. They also considered what other medications a patient is taking and any personal preferences. If clinicians would consider genetics, here is what they could learn about prescribing the common painkiller codeine. Typically the body produces an enzyme called CYP2D6 that breaks down the drug into its active ingredient, morphine, which provides pain relief. Yet as many as 10 percent of patients have genetic variants that produce too little of the enzyme, so almost no codeine gets turned into morphine. These people get little or no help for their pain. About 2 percent of the population has the reverse problem. They have too many copies of the gene that produces the enzyme, leading to overproduction. For them, a little codeine can quickly turn into too much morphine, which can lead to a fatal overdose.

…Still, fewer than 10 hospitals around the country—including Maryland, Vanderbilt and St. Jude—are offering pharmacogenomic tests to certain patients. The other main obstacle to wider use, besides reimbursement, is the lack of a prescribing road map. Many doctors were educated in an era before such testing was available so they do not even think to order them. And a lot of physicians would likely find they are not equipped to understand the results.

More here.

Monday, December 17, 2018

Are Big Questions a Good Idea?

by Emrys Westacott

Philosophers are supposed to ask Big Questions. The Big Questions is the title of a popular introduction to philosophy and of a long-running BBC programme in which people discuss their ethical and religious perspectives. But since we philosophers, following in the footsteps of Socrates, claim to practice critical thinking, it behooves us to ask whether Big Questions are a good idea.

Philosophers are supposed to ask Big Questions. The Big Questions is the title of a popular introduction to philosophy and of a long-running BBC programme in which people discuss their ethical and religious perspectives. But since we philosophers, following in the footsteps of Socrates, claim to practice critical thinking, it behooves us to ask whether Big Questions are a good idea.

It’s not easy to say precisely what makes a question big; but we can at least give a few examples form the history of philosophy so that we have some idea what we’re talking about:

- What is the meaning of life?

- What is the nature of ultimate reality?

- What is Being?

- Is there a god?

- Is there some sort of cosmic justice?

- What is the self ?

- Does a person’s self (mind, soul) persist after death?

- Do we have free will?

- Why be moral?

- What is the good life for a human being?

- What are the foundations of our knowledge?

- What are the limits to what we can know?

- What is truth?

- What is the good?

- What is justice?

- What is virtue?

- What is beauty?

- What is life?

- Why is there something rather than nothing?

In modern times such questions have met with various fates. The cultural ascendancy of natural science was accompanied by skepticism toward what Kant calls “speculative metaphysics.” Simply put, we can’t have knowledge of matters that lie beyond what we can possibly experience. So we can’t know if there is a god, or if we have immortal souls, or if there is cosmic justice. In his Critique of Pure Reason (1781) Kant claimed that in denying knowledge he was “making room for faith.” Inevitably, though, faith in God, the soul and the afterlife has declined dramatically since Kant’s time, especially among intellectuals. There are virtually no articles published in philosophy journals today that treat the existence of God or the immortality of the soul as live issues. Science does not explicitly teach us that there is no God and no heaven, any more than it teaches us that there are no fairies or vampires. But the default attitude of most professional philosophers today is that in such matters the absence of evidence amounts to evidence of absence. Read more »

In his Critique of Pure Reason (1781) Kant claimed that in denying knowledge he was “making room for faith.” Inevitably, though, faith in God, the soul and the afterlife has declined dramatically since Kant’s time, especially among intellectuals. There are virtually no articles published in philosophy journals today that treat the existence of God or the immortality of the soul as live issues. Science does not explicitly teach us that there is no God and no heaven, any more than it teaches us that there are no fairies or vampires. But the default attitude of most professional philosophers today is that in such matters the absence of evidence amounts to evidence of absence. Read more »

Women on Strike

by Abigail Akavia

Tuesday, December 4th, was a day of widespread women’s protests against gender-based violence in Israel. A general women’s strike was declared, which garnered the support of governmental departments, municipalities, unions and major corporations. Demonstrations were held across the country: roads were blocked; water in public fountains was dyed red; at Habima Square in Tel Aviv, an installation of red shoes inspired by the work of Mexican artist Elina Chauvet commemorated victims of domestic violence. The principal event was a mass rally in Tel Aviv Rabin’s Square. The vigils, protests, and marches, organized by dozens of feminist groups led by the Red Flag Coalition, gained an all-encompassing female empowerment vibe à la worldwide women’s marches, pussy riots, and the MeToo movement. The demonstrations were aimed specifically against the government’s with regard to the prevention of domestic violence, and its neglect to finance a multi-departmental program to address the issue—a program it had already principally approved a year ago.

A mere week afterwards, an honorary prize for “contribution to Israeli song” was given at the Knesset, the seat of Israeli parliament, to Eyal Golan. Golan, an immensely popular singer and performer, was investigated four years ago for (allegedly) repeatedly prostituting minor girls, with the help of his father. The criminal case against both of them was closed for “lack of evidence.” Golan was not the sole recipient of the prize, but his presence at the Knesset was controversial and sparked a protest of its own. (Some of the other prize recipients chose to absent themselves.) Though the prize and the ceremony were the initiative of one Knesset member and not an official event of the parliament, the Knesset Chairman is authorized to prevent such a ceremony from taking place. The fact that he didn’t, and that the Knesset as an institution—if not officially then at least by proxy—celebrated a man who casually abused girls, sends a perverted, corrupt message to Israeli women and the public at large. It proves the necessity of women’s disruptive activism in Israel today and, at once, its limited pragmatic effect so far. Read more »

The Third Threat

by Joan Harvey

When the air becomes uraneous

We will all go simultaneous

Yes, we all will go together

When we all go together

Yes we all will go together when we go

—Tom Lehrer, “We Will All Go Together When We Go”

You know what uranium is, right? It’s this thing called nuclear weapons. And other things. Like lots of things are done with uranium. Including some bad things.

—Donald J. Trump

The tide has turned, the Democrats have the House, Mueller showers us with gifts each day, hope lurches upward, though past trauma urges us to perpetually rein it in. We’re glued to the news, good or bad, to a level of destruction, corruption, drama, and scandal so great, it’s impossible to keep up with even a small part of it. We can’t process it all; we can barely find effective ways to act besides logging in with the Resistance, enjoying clever tweets, and imbibing good quantities of gin.

It’s hard to argue with Yuval Harari that the three main threats to our existence are climate change, artificial intelligence (and with it biotechnology), and nuclear war. And yet for most of us, saving some shreds of democracy (and decency) come first. Climate change certainly is on our minds, in the news every day, present to us as we watch so many people and animals suffer and homes and habitats destroyed. Then there’s AI, newest of the threats, still kind of sci-fi and sexy, and because we all work with computers and also have watched Facebook turn into a monster, the dangers of AI also do not feel so distant. But, left behind, neglected, is the oldest of these three manmade megathreats to the world, the peril of nuclear war. It’s a danger that has not diminished over time and is in actuality increasing. But even though it has the potential to be the most immediately destructive, it can feel the most remote.

I’m one of the few people who grew up on a homesite with a bomb shelter, a dark cold cave dug into a hill on my parents’ property. There may still be canned goods in there from the ‘60s, for all I know. Read more »