Aunties love it when seafood is on sale

In summertime, the women

in my family spin sagoo

like planets, make

even saturn blush.

They split the leaves

of kang kong with

riverbed softness.

They are precise;

measure rice by palm lines

with laughter and season

broth made of creature’s last gasps.

You’d swear they were

teenagers again, talking gossip

stretching limbs

elastic, durable, like seaweed.

Come dinner time,

skilled mouths slurp

through the domes of

shrimp and crab.

They

prize the fat,

the angles of their teeth

splinter claw, snap sinew,

dip tart into sweet

then back again;

bitterness balanced,

succulence on succulence,

is to find flesh from even the

smallest of spaces.

Women who swallow whole,

who make a pile of bones,

who suck teeth,

taste every morsel,

so that all that is left

is a quiet room

and shells of what once was.

To the daughters of dried fish nets

whose dreams dragged on sand,

dragged to this country,

they bring home recipe years later,

flick joints to garlic,

salabat to the sick,

culinary remix, teach cousins,

this is how we stay alive,

mourning in the Midwest

by taste bud.

Afterwards, they keep the ocean

husks for another meal

because to get a good deal

is to double.

And anybody from the island

will tell you,

that is where true flavor is

and what is hunger

anyway, but the carving

out of emptiness,

the learning you gotta always

always save something

for later?

by Kay Ulanday Barrett

from Split This Rock

As the bus nears downtown Katowice, the site of the 24th annual UN Climate Conference, or COP24, two huge funnels loom into view: a coal mine. There are fourteen in Katowice, although only two remain active. The rest lie strewn across the city like dormant volcanoes. The UN insists that Katowice is in transition—“from black to green,” says a welcome video at the opening ceremony—and claims that 40 percent of the city’s surface area is devoted to green spaces. Judging by the looks on their faces as they ogle the coal mine, the delegates on this bus do not see it that way. When they disembark, one of them scrunches up his nose at the unmistakable smell—rich and smoky—that wafts from an alleyway. Many Katowicians still burn coal for heat.

As the bus nears downtown Katowice, the site of the 24th annual UN Climate Conference, or COP24, two huge funnels loom into view: a coal mine. There are fourteen in Katowice, although only two remain active. The rest lie strewn across the city like dormant volcanoes. The UN insists that Katowice is in transition—“from black to green,” says a welcome video at the opening ceremony—and claims that 40 percent of the city’s surface area is devoted to green spaces. Judging by the looks on their faces as they ogle the coal mine, the delegates on this bus do not see it that way. When they disembark, one of them scrunches up his nose at the unmistakable smell—rich and smoky—that wafts from an alleyway. Many Katowicians still burn coal for heat. We made each other’s acquaintance among things and by way of them. Once again, I don’t remember anything about the subject of conversation: what I do remember is the perfect harmony the bread and wine afforded us. For instance, I could immediately see that you, Stravinsky, like me, love bread when it’s good and wine when it’s good, bread and wine together, each for the other, each through the other. This is where your personality and, by the same token, your art—in other words, all of you—begin; I took the outermost path to this inner knowledge, the most terrestrial road. There was no “artistic” or “aesthetic” discussion, if memory serves; but I can still see you smiling at your full glass, the bread you were brought, the carafe. I can see you picking up your knife and the quick, decisive gesture with which you separated the rind from the lovely semi-firm cheese. I came to know you amid and through the kind of pleasure I saw you derive from things, the so-called “humblest” ones; a certain brand and quality of delectation that gets the whole being interested. I love the body, as you know, because I can scarcely separate it from the soul; mostly I love the great unity of their total participation in such a maneuver, where the abstract and concrete find themselves reconciled, where they explain and elucidate one another. For many young ladies, a musician is a big forehead with “ideas” inside (God only knows which ones!): you showed me right away that the musician who invents a sound might be the furthest thing from a specialist, and that he distills it from a living substance, a substance common to all of us but with which one must first make direct and human contact.

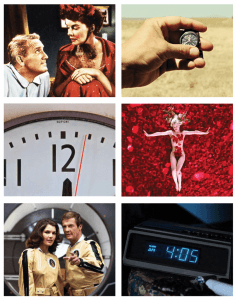

We made each other’s acquaintance among things and by way of them. Once again, I don’t remember anything about the subject of conversation: what I do remember is the perfect harmony the bread and wine afforded us. For instance, I could immediately see that you, Stravinsky, like me, love bread when it’s good and wine when it’s good, bread and wine together, each for the other, each through the other. This is where your personality and, by the same token, your art—in other words, all of you—begin; I took the outermost path to this inner knowledge, the most terrestrial road. There was no “artistic” or “aesthetic” discussion, if memory serves; but I can still see you smiling at your full glass, the bread you were brought, the carafe. I can see you picking up your knife and the quick, decisive gesture with which you separated the rind from the lovely semi-firm cheese. I came to know you amid and through the kind of pleasure I saw you derive from things, the so-called “humblest” ones; a certain brand and quality of delectation that gets the whole being interested. I love the body, as you know, because I can scarcely separate it from the soul; mostly I love the great unity of their total participation in such a maneuver, where the abstract and concrete find themselves reconciled, where they explain and elucidate one another. For many young ladies, a musician is a big forehead with “ideas” inside (God only knows which ones!): you showed me right away that the musician who invents a sound might be the furthest thing from a specialist, and that he distills it from a living substance, a substance common to all of us but with which one must first make direct and human contact. Between 2007 and 2010, the artist Christian Marclay and a team of researchers scoured tens of thousands of films for scenes and shots in which time was in some way incorporated. It could be a close-up of a watch or a sand timer, the $10m four-faced opal clock at New York Grand Central Station or a novelty timepiece showing two pigs humping merrily (from Mighty Aphrodite). Better yet, it might be an instance in which time plays a pivotal role: the clock tower struck by lightning in Back to the Future, or Harold Lloyd clinging to the minute hand high above Los Angeles in Safety Last!

Between 2007 and 2010, the artist Christian Marclay and a team of researchers scoured tens of thousands of films for scenes and shots in which time was in some way incorporated. It could be a close-up of a watch or a sand timer, the $10m four-faced opal clock at New York Grand Central Station or a novelty timepiece showing two pigs humping merrily (from Mighty Aphrodite). Better yet, it might be an instance in which time plays a pivotal role: the clock tower struck by lightning in Back to the Future, or Harold Lloyd clinging to the minute hand high above Los Angeles in Safety Last!

Author Hannah Lillith Assadi revels in the contradictions of her identity: She was born in the United States to a Jewish mother and a Palestinian father. Her debut novel, “Sonora,” is a paean to the vexing process of how a second-generation immigrant struggles to come to terms with herself and history. Israeli-American novelist and poet Moriel Rothman-Zecher explores similar themes in “Sadness Is a White Bird,” revealing the agonizing internal struggle of an American-Israeli man who cannot balance his friendship with two Palestinians and his enrollment in the Israeli army. Both are examples of Millennial writers with Israeli and Palestinian heritage living in the US who are forging novel perspectives on the conflict.

Author Hannah Lillith Assadi revels in the contradictions of her identity: She was born in the United States to a Jewish mother and a Palestinian father. Her debut novel, “Sonora,” is a paean to the vexing process of how a second-generation immigrant struggles to come to terms with herself and history. Israeli-American novelist and poet Moriel Rothman-Zecher explores similar themes in “Sadness Is a White Bird,” revealing the agonizing internal struggle of an American-Israeli man who cannot balance his friendship with two Palestinians and his enrollment in the Israeli army. Both are examples of Millennial writers with Israeli and Palestinian heritage living in the US who are forging novel perspectives on the conflict. Implanted electronics can steady hearts, calm tremors, and heal wounds—but at a cost. These machines are often large, obtrusive contraptions with batteries and wires, which require surgery to implant and sometimes need replacement. That’s changing.

Implanted electronics can steady hearts, calm tremors, and heal wounds—but at a cost. These machines are often large, obtrusive contraptions with batteries and wires, which require surgery to implant and sometimes need replacement. That’s changing. A century ago in late October, a mutiny broke out in the Imperial German Navy. In Wilhelmshaven on the North Sea, hungry, demoralized sailors refused to follow orders in preparation for one last skirmish with the British for the sake of their officers’ vainglory. Unsure of the crew’s loyalty, the officers ordered the fleet to port in Kiel, but by November 4 the rebels had taken over the city and established a workers’ and soldiers’ council. Their cries for “peace and bread” reverberated throughout the empire, and over the following week revolutionaries captured a string of towns and provinces. On November 9 the red tide had

A century ago in late October, a mutiny broke out in the Imperial German Navy. In Wilhelmshaven on the North Sea, hungry, demoralized sailors refused to follow orders in preparation for one last skirmish with the British for the sake of their officers’ vainglory. Unsure of the crew’s loyalty, the officers ordered the fleet to port in Kiel, but by November 4 the rebels had taken over the city and established a workers’ and soldiers’ council. Their cries for “peace and bread” reverberated throughout the empire, and over the following week revolutionaries captured a string of towns and provinces. On November 9 the red tide had  One is dean of Yale’s medical school. Another is the director of a cancer center in Texas. A third is the next president of the most prominent society of cancer doctors.

One is dean of Yale’s medical school. Another is the director of a cancer center in Texas. A third is the next president of the most prominent society of cancer doctors. Immigration and diversity politics dominate our political and public debates. Disagreements about these issues lie behind the rise of populist politics on the left and the right, as well as the growing polarization of our societies more widely. Unless we find a way of side-stepping the extremes and debating these issues in an evidence-led, analytical way then the moderate, pluralistic middle will buckle and give way.

Immigration and diversity politics dominate our political and public debates. Disagreements about these issues lie behind the rise of populist politics on the left and the right, as well as the growing polarization of our societies more widely. Unless we find a way of side-stepping the extremes and debating these issues in an evidence-led, analytical way then the moderate, pluralistic middle will buckle and give way. By the time Eisenberg started as an apprentice, several events suggested that the gender barrier in construction, and in other industries, could finally be cracked. It had been 15 years since the passage of the Equal Pay Act, which prohibited wage differentials based on sex, and 14 years since the Civil Rights Act, which outlawed discrimination based on race, color, religion, national origin, and—at the eleventh hour—sex. (Labor unions strongly opposed the latter.) Almost a decade earlier, Gloria Steinem’s article “After Black Power, Women’s Liberation,” published in New York magazine, created small seismic shifts in homes and workplaces across America. The Equal Rights Amendment had finally passed, nearly a half-century after it was introduced, and was awaiting state ratification. (The ERA remains in constitutional limbo to this day. A faction of conservative women thwarted its passage, arguing that it would lead to the draft and eventually to unisex bathrooms.)

By the time Eisenberg started as an apprentice, several events suggested that the gender barrier in construction, and in other industries, could finally be cracked. It had been 15 years since the passage of the Equal Pay Act, which prohibited wage differentials based on sex, and 14 years since the Civil Rights Act, which outlawed discrimination based on race, color, religion, national origin, and—at the eleventh hour—sex. (Labor unions strongly opposed the latter.) Almost a decade earlier, Gloria Steinem’s article “After Black Power, Women’s Liberation,” published in New York magazine, created small seismic shifts in homes and workplaces across America. The Equal Rights Amendment had finally passed, nearly a half-century after it was introduced, and was awaiting state ratification. (The ERA remains in constitutional limbo to this day. A faction of conservative women thwarted its passage, arguing that it would lead to the draft and eventually to unisex bathrooms.) Palestine’s colonization doesn’t just take the form of checkpoints, walls, eradicated villages, testimonies from families with concrete barriers through their homes; it takes the form of an opulent city whose residents are convinced they live in the greatest city in the world. It was here, at this moment, when I began to realize the weight of what we lost, when I realized my memory of Palestine was a misappropriation of my displaced family’s lived experience, and no matter how much learning and unlearning I did, nothing would restore that original memory. Nothing would reconcile my experience of Palestine with my family’s collective memory. Nothing would resurrect the country this once was.

Palestine’s colonization doesn’t just take the form of checkpoints, walls, eradicated villages, testimonies from families with concrete barriers through their homes; it takes the form of an opulent city whose residents are convinced they live in the greatest city in the world. It was here, at this moment, when I began to realize the weight of what we lost, when I realized my memory of Palestine was a misappropriation of my displaced family’s lived experience, and no matter how much learning and unlearning I did, nothing would restore that original memory. Nothing would reconcile my experience of Palestine with my family’s collective memory. Nothing would resurrect the country this once was. In 1905, defeated by Japan and facing insurrection in the major cities and financial catastrophe, Russia’s tsar and his government were forced to retreat from autocracy and create a parliament (the Duma). Censorship, already weak and inconsistent, virtually collapsed. By then, there were plenty of printing presses, legal and illegal, along with cheap paper and card and, most surprisingly, an efficient postal system of a kind that modern Russians can only dream of. Moscow and St Petersburg had six collections a day; a letter sent from the Crimea to France took just four days to arrive. By 1913 Moscow alone handled thirteen million letters a year. Postcards, first introduced in 1872, were the cheapest form of communication – a mere three-kopeck stamp took a card anywhere in the empire. It was some time before cards could be illustrated, and it was later still that it became no longer obligatory to confine the message to a line or two scrawled over the illustration. Regulations eventually relaxed so much that giant postcards much larger than the standard 9 x 14 cm were accepted.

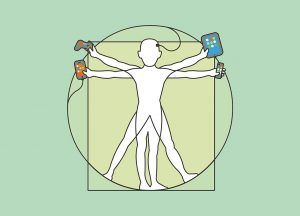

In 1905, defeated by Japan and facing insurrection in the major cities and financial catastrophe, Russia’s tsar and his government were forced to retreat from autocracy and create a parliament (the Duma). Censorship, already weak and inconsistent, virtually collapsed. By then, there were plenty of printing presses, legal and illegal, along with cheap paper and card and, most surprisingly, an efficient postal system of a kind that modern Russians can only dream of. Moscow and St Petersburg had six collections a day; a letter sent from the Crimea to France took just four days to arrive. By 1913 Moscow alone handled thirteen million letters a year. Postcards, first introduced in 1872, were the cheapest form of communication – a mere three-kopeck stamp took a card anywhere in the empire. It was some time before cards could be illustrated, and it was later still that it became no longer obligatory to confine the message to a line or two scrawled over the illustration. Regulations eventually relaxed so much that giant postcards much larger than the standard 9 x 14 cm were accepted. In his 1909 short story The Machine Stops, E. M. Forster imagined a future in which people live in isolation underground, their needs serviced by an all-powerful ‘machine’. Human activity consists mainly of remote communication — face-to-face interaction is frowned upon. Ultimately, the title of the story plays out: the machine stops, civilization collapses, and the future of humanity is left to the surface-dwellers who avoided dependency. The story has been lauded not only for its prescient imagining of something like our hyperconnected Internet age, but also for its insights into the human impact of an all-powerful technology. We are now starting to grapple with similar questions. What do we lose when we cede autonomy to technology? Are we becoming dependent on it? And what is digital technology doing to our minds?

In his 1909 short story The Machine Stops, E. M. Forster imagined a future in which people live in isolation underground, their needs serviced by an all-powerful ‘machine’. Human activity consists mainly of remote communication — face-to-face interaction is frowned upon. Ultimately, the title of the story plays out: the machine stops, civilization collapses, and the future of humanity is left to the surface-dwellers who avoided dependency. The story has been lauded not only for its prescient imagining of something like our hyperconnected Internet age, but also for its insights into the human impact of an all-powerful technology. We are now starting to grapple with similar questions. What do we lose when we cede autonomy to technology? Are we becoming dependent on it? And what is digital technology doing to our minds?