by Christopher Bacas

Guinea and Redhead were part of a large food chain. Beyond campus’ freshly-baked sidewalks, a Cowboy Mafia ferried contraband from the south. They landed small prop planes on ranch land outside of town, cut powder with dental anesthetics and broke up the bales. Their wares clumped on our cafeteria trays and glinted in tiny screw-top bottles. The capo, a local big-hat business man,who ran a palatial kicker-dance hall and owned the ranch. That legit business and his crew’s discipline kept them out of jail. Maybe a hat full of cash in the bargain.

Guinea and Redhead were part of a large food chain. Beyond campus’ freshly-baked sidewalks, a Cowboy Mafia ferried contraband from the south. They landed small prop planes on ranch land outside of town, cut powder with dental anesthetics and broke up the bales. Their wares clumped on our cafeteria trays and glinted in tiny screw-top bottles. The capo, a local big-hat business man,who ran a palatial kicker-dance hall and owned the ranch. That legit business and his crew’s discipline kept them out of jail. Maybe a hat full of cash in the bargain.

My Trumpet buddy shared an apartment in a low-rise student complex. Trumpet’s Roomie was in with the Cowboys. I found out when I made a visit. From outside, the shitty drywall construction leaked sound and odors like a window screen. Inside, eucalyptus gas wrapped around my head. I knew Roomie a little. He didn’t seem to remember. Wide-eyed, fidgeting, he appraised me.

“You cool?”

I reckoned I was. In his bedroom, he kicked aside some laundry and slid open a door. On the floor, a bulging black Hefty bag yawned. Inside, Tolkein magic: lichen grown thigh-deep, whispering in shadow. Despite mind-expanding potential, there was no joy in babysitting a large ingot of fools’ gold. Read more »

The new year approaches and with it comes our annual habit of self-promises in the form of New Year’s resolutions. Statistically speaking, though, 2019 won’t be your year. While many of us start strong, we tend to flounder come February, and studies cite the failure rate to be anywhere from 80 to 90 percent.

The new year approaches and with it comes our annual habit of self-promises in the form of New Year’s resolutions. Statistically speaking, though, 2019 won’t be your year. While many of us start strong, we tend to flounder come February, and studies cite the failure rate to be anywhere from 80 to 90 percent. The ongoing three-way public-relations car wreck involving Washington, Facebook, and

The ongoing three-way public-relations car wreck involving Washington, Facebook, and

On February 22, 1942, the Austrian writer Stefan Zweig and his second wife went to the bedroom of a rented house in Petrópolis, Brazil. They lay down—she in a kimono, he in a shirt and tie—after taking an enormous dose of barbiturates. When news of their suicides broke, it was reported as a matter of worldwide significance. The New York Times carried the news on its front page, alongside reports of the rout of Japanese forces in Bali and of a broadcast address by President Roosevelt. An editorial the next day, titled “One of the Dispossessed,” saw in Zweig’s final act “the problems of the exile for conscience sake.” Zweig, a Jew, had left Austria in 1934, living in England and New York before the final move to Brazil, and his work had been banned and vilified across the German-speaking world. In his suicide note, he spoke of “my own language having disappeared from me and my spiritual home, Europe, having destroyed itself.” He concluded, “I salute all my friends! May it be granted them yet to see the dawn after the long night! I, all too impatient, go on before.”

On February 22, 1942, the Austrian writer Stefan Zweig and his second wife went to the bedroom of a rented house in Petrópolis, Brazil. They lay down—she in a kimono, he in a shirt and tie—after taking an enormous dose of barbiturates. When news of their suicides broke, it was reported as a matter of worldwide significance. The New York Times carried the news on its front page, alongside reports of the rout of Japanese forces in Bali and of a broadcast address by President Roosevelt. An editorial the next day, titled “One of the Dispossessed,” saw in Zweig’s final act “the problems of the exile for conscience sake.” Zweig, a Jew, had left Austria in 1934, living in England and New York before the final move to Brazil, and his work had been banned and vilified across the German-speaking world. In his suicide note, he spoke of “my own language having disappeared from me and my spiritual home, Europe, having destroyed itself.” He concluded, “I salute all my friends! May it be granted them yet to see the dawn after the long night! I, all too impatient, go on before.” I am glad,’ wrote the acclaimed American philosopher Susan Wolf, ‘that neither I nor those about whom I care most’ are ‘moral saints’. This declaration is one of the opening remarks of a landmark essay in which Wolf imagines what it would be like to be morally perfect. If you engage with Wolf’s thought experiment, and the conclusions she draws from it, then you will find that it offers liberation from the trap of moral perfection. Wolf’s

I am glad,’ wrote the acclaimed American philosopher Susan Wolf, ‘that neither I nor those about whom I care most’ are ‘moral saints’. This declaration is one of the opening remarks of a landmark essay in which Wolf imagines what it would be like to be morally perfect. If you engage with Wolf’s thought experiment, and the conclusions she draws from it, then you will find that it offers liberation from the trap of moral perfection. Wolf’s  Over the weekend, the New York Times Book Review

Over the weekend, the New York Times Book Review  Q: In simple terms, what defines a human right?

Q: In simple terms, what defines a human right? The clock says 3:30 am. Is that early or late? Wrapped in a blanket I go into the living room. I open the door and step onto the patio. It’s too warm for December. An almost full moon blurs into the clouds. In the distance, the highway hums.

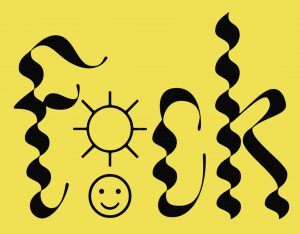

The clock says 3:30 am. Is that early or late? Wrapped in a blanket I go into the living room. I open the door and step onto the patio. It’s too warm for December. An almost full moon blurs into the clouds. In the distance, the highway hums. Ah, fuck! What an indispensable, multitasker of a word it has become! No longer relegated to that marginalized category once known as profanity, fuck now wears many syntactical hats and is a staple of Trump-era vocabulary. In addition to being a fun way to embed a little malediction into words that otherwise might be chalked up as run-of-the-mill resistance jargon (“inter-fucking-sectional,” “patri-fucking-archy”), fuck is enjoying a long tenure as a synonym for shit. Not giving a shit (which sounds downright 1980s) has now evolved into “not giving a fuck.” By extension, you can now describe something as “[adjective] as fuck” (abbreviated for tweeting purposes to “AF”) You can be tired as fuck, sick as fuck, angry as fuck, and so on. I guess if you find yourself in an especially tragic situation (for instance, banned from Twitter), you can be fucked as fuck.

Ah, fuck! What an indispensable, multitasker of a word it has become! No longer relegated to that marginalized category once known as profanity, fuck now wears many syntactical hats and is a staple of Trump-era vocabulary. In addition to being a fun way to embed a little malediction into words that otherwise might be chalked up as run-of-the-mill resistance jargon (“inter-fucking-sectional,” “patri-fucking-archy”), fuck is enjoying a long tenure as a synonym for shit. Not giving a shit (which sounds downright 1980s) has now evolved into “not giving a fuck.” By extension, you can now describe something as “[adjective] as fuck” (abbreviated for tweeting purposes to “AF”) You can be tired as fuck, sick as fuck, angry as fuck, and so on. I guess if you find yourself in an especially tragic situation (for instance, banned from Twitter), you can be fucked as fuck. The English word ‘boredom’, the French ‘ennui’, and the German ‘Langeweile’ are hardly synonyms – the first possibly deriving from the activity of boring wood, the next having to do with a feeling of annoyance, the last, which means ‘long while’, referring to the slow passing of time. Then again, if we think someone is boring they will probably be annoying, and time spent with them will feel unpleasantly long, so the terms make related sense. The relationship to the world involved in each term is evidently negative. ‘Langeweile’ implies, for example, that the meaningfulness of time, which is structured by desires, intentions, hope, anticipation, etc., has been reduced to a sense of time as empty because it lacks these projective qualities. However, boredom may not be thought of as simply negative. Nietzsche, for example, contends that boredom has a dialectical counterpart: ‘For the thinker and for all inventive spirits boredom is that unpleasant “doldrums” of the soul which precedes the happy journey and merry winds; he has to bear it, has to wait for its effect on him’. Boredom can, therefore, be seen as necessary to the generation of new meaning.

The English word ‘boredom’, the French ‘ennui’, and the German ‘Langeweile’ are hardly synonyms – the first possibly deriving from the activity of boring wood, the next having to do with a feeling of annoyance, the last, which means ‘long while’, referring to the slow passing of time. Then again, if we think someone is boring they will probably be annoying, and time spent with them will feel unpleasantly long, so the terms make related sense. The relationship to the world involved in each term is evidently negative. ‘Langeweile’ implies, for example, that the meaningfulness of time, which is structured by desires, intentions, hope, anticipation, etc., has been reduced to a sense of time as empty because it lacks these projective qualities. However, boredom may not be thought of as simply negative. Nietzsche, for example, contends that boredom has a dialectical counterpart: ‘For the thinker and for all inventive spirits boredom is that unpleasant “doldrums” of the soul which precedes the happy journey and merry winds; he has to bear it, has to wait for its effect on him’. Boredom can, therefore, be seen as necessary to the generation of new meaning. For the sociologist

For the sociologist  Frank kameny, the

Frank kameny, the  ON OCTOBER 2, 2018

ON OCTOBER 2, 2018 The first time Trump paid attention to any of this was when he read about it in the newspaper. The story revealed that Trump’s very own transition team had raised several million dollars to pay the staff. The moment he saw it, Trump called Steve Bannon, the chief executive of his campaign, from his office on the 26th floor of Trump Tower, and told him to come immediately to his residence, many floors above. Bannon stepped off the elevator to find Christie seated on a sofa, being hollered at. Trump was apoplectic, yelling: You’re stealing my money! You’re stealing my fucking money! What the fuck is this?

The first time Trump paid attention to any of this was when he read about it in the newspaper. The story revealed that Trump’s very own transition team had raised several million dollars to pay the staff. The moment he saw it, Trump called Steve Bannon, the chief executive of his campaign, from his office on the 26th floor of Trump Tower, and told him to come immediately to his residence, many floors above. Bannon stepped off the elevator to find Christie seated on a sofa, being hollered at. Trump was apoplectic, yelling: You’re stealing my money! You’re stealing my fucking money! What the fuck is this?