Category: Recommended Reading

Overlooking Guantánamo

Stephen Benz at The NER:

In such circumstances, the “Guantánamo Blues” that the anonymous writer struggled with in the 1930s became all the more acute. Visiting journalists in the 1960s and 1970s reported on racial tensions, drug and alcohol problems, and occasional violence. According to a 1973 article in Esquire, “Guantánamo is a good place to become an alcoholic. During the last twelve months gin has been the leading seller at the base Mini-Mart, with vodka a close second.”

In such circumstances, the “Guantánamo Blues” that the anonymous writer struggled with in the 1930s became all the more acute. Visiting journalists in the 1960s and 1970s reported on racial tensions, drug and alcohol problems, and occasional violence. According to a 1973 article in Esquire, “Guantánamo is a good place to become an alcoholic. During the last twelve months gin has been the leading seller at the base Mini-Mart, with vodka a close second.”

A strange place to begin with, Gitmo became even stranger during the Cold War period, given that it was a US military facility on the sovereign territory of a country aligned with the Soviet bloc. By the time I stood at the Malones Lookout in 1998, with the Cold War supposedly a thing of the past, Gitmo seemed like a weird anachronism of both neo-colonialism and the Cold War. My opinion at the time was that Guantánamo was outdated and unnecessary; keeping it seemed counterproductive, and returning it to Cuba seemed like the right thing to do. I had said as much in some of my conversations with Cubans. In fact, I had told many of my interlocutors that I had a gut feeling President Clinton was going to normalize relations with Cuba and begin the process of returning Guantánamo before he left office in two years’ time.

more here.

Friday Poem

Lunar Eclipse

A maid comes running into the house

talking about things beyond belief,

about the sky all turned to blue glass,

the moon to a crystal of black quartz.

It rose a full ten parts round tonight,

but now it’s just a bare sliver of light.

My wife hurries off to fry roundcakes,

and my son starts banging on mirrors:

it’s awfully shallow thinking, I know,

but that urge to restore is beautiful.

The night deepens. The moon emerges,

then goes on shepherding stars west.

by Mei Yao-ch’en (1002-1060)

from Mountain Home: The Wilderness Poetry of Ancient China

Counterpoint, 2002

translated from the Chinese by David Hinton

What Do Religious Voters Want?

Adam Willis at The Boston Globe:

HOW HAS A foul-mouthed, womanizing, Biblically illiterate populist earned the broad democratic endorsement of socially conservative, Christian voters? It’s a question that has prompted much liberal hand-wringing in the United States, but it has found an even more extreme manifestation in the overwhelmingly Catholic Philippines.

In May 2016, months before Donald Trump claimed the White House, the Philippines voted Rodrigo Duterte to that country’s presidency. A crass, fire-breathing strongman with a shadowy history of violence in the southern city of Davao, where he earned the nickname “the Death Squad Mayor,” Duterte won a landslide plurality on fantastical campaign promises to clear Metro Manila traffic — some of the worst in the world — in 100 days, to weed out corruption at its roots, and, in his banner program, to scrub the country of crime and poverty through an unforgiving war on drugs.

more here.

The Enduring, Incandescent Power of Kate Bush

Margaret Talbot at The New Yorker:

Female pop geniuses who exercise their gifts in rampant, restless fashion over decades, writing, performing, and producing their own work, are as rare as black opals. Shape-shifting brilliance and an airy indifference to what’s expected of you are not the music industry’s favorite assets in any performer, but they are probably easier to accept in a man than in a woman. And such a musician, even today, is subject to the same pressures that have always hindered women’s artistic expression. Like the thwarted writers whom Virginia Woolf described in “A Room of One’s Own,” the female pop original is “strained and her vitality lowered by the need of opposing this, of disproving that”—by the refusal to please and accommodate that only a deep belief in one’s own gift can counteract. “What genius, what integrity it must have required in the face of all that criticism, in the midst of that purely patriarchal society,” Woolf writes, “to hold fast to the thing as they saw it without shrinking.”

Female pop geniuses who exercise their gifts in rampant, restless fashion over decades, writing, performing, and producing their own work, are as rare as black opals. Shape-shifting brilliance and an airy indifference to what’s expected of you are not the music industry’s favorite assets in any performer, but they are probably easier to accept in a man than in a woman. And such a musician, even today, is subject to the same pressures that have always hindered women’s artistic expression. Like the thwarted writers whom Virginia Woolf described in “A Room of One’s Own,” the female pop original is “strained and her vitality lowered by the need of opposing this, of disproving that”—by the refusal to please and accommodate that only a deep belief in one’s own gift can counteract. “What genius, what integrity it must have required in the face of all that criticism, in the midst of that purely patriarchal society,” Woolf writes, “to hold fast to the thing as they saw it without shrinking.”

more here.

Elaine Pagels is famous for asking hard questions. Her latest: ‘Why Religion?’

Harry Bruinius in The Christian Scence Monitor:

Elaine Pagels, people say, is a heretic. It’s an ancient accusation, of course, and it hardly wields as much power as it used to, especially in the free-wheeling religious landscape of America. And Ms. Pagels is, in fact, one of the globe’s foremost experts in early Christian heresies. But as a woman who has been disrupting established orthodoxies for nearly half a century, her name still has the power to arouse disdain in certain religious circles. “You know, people have sometimes called me ‘Elaine Pagan’,” the Princeton University professor says during an interview with the Monitor, smiling as she reflects on the trajectory of her life’s work, her many orthodox critics, and her new book, “Why Religion? A Personal Story.” Forty years ago, Pagels’ first book, “The Gnostic Gospels,” was an unlikely sensation. A young historian without tenure and a specialist who read 1st century languages like Coptic, she was one of the first to illuminate an ancient trove of long-lost gospels and other writings about Jesus, writings which were simply stumbled upon by a local farmer near the Egyptian town Nag Hammadi in 1945.

Elaine Pagels, people say, is a heretic. It’s an ancient accusation, of course, and it hardly wields as much power as it used to, especially in the free-wheeling religious landscape of America. And Ms. Pagels is, in fact, one of the globe’s foremost experts in early Christian heresies. But as a woman who has been disrupting established orthodoxies for nearly half a century, her name still has the power to arouse disdain in certain religious circles. “You know, people have sometimes called me ‘Elaine Pagan’,” the Princeton University professor says during an interview with the Monitor, smiling as she reflects on the trajectory of her life’s work, her many orthodox critics, and her new book, “Why Religion? A Personal Story.” Forty years ago, Pagels’ first book, “The Gnostic Gospels,” was an unlikely sensation. A young historian without tenure and a specialist who read 1st century languages like Coptic, she was one of the first to illuminate an ancient trove of long-lost gospels and other writings about Jesus, writings which were simply stumbled upon by a local farmer near the Egyptian town Nag Hammadi in 1945.

…Still, at the heart of “Why Religion?” is a quiet meditation on the meaning of human mortality, and the grief and soul-shattering anguish the famous scholar experienced over the course her life. More than 25 years ago, her firstborn son, then 6, collapsed in her arms and died of a rare respiratory illness. Just a year later, with her two younger children under her care, she lost her husband, who fell to his death while hiking in Colorado. “I needed to write this, partly because I needed to bring forth those experiences that I had buried, because they were so difficult to deal with at the time,” Pagels says of the reasons for writing such an intensely personal book. “And I think for anyone, whether it’s people who write poetry or music or any other kind of expressive forms, you can ask, ‘Why do we really need to do that?’ ”

More here.

Here are 6 hints that Baby Jesus stories were late additions to early Christian lore

Valerie Tarico in AlterNet:

Picture a creche with baby Jesus in a manger and shepherds and angels and three kings and a star over the stable roof. We think of this traditional scene as representing the Christmas story, but it actually mixes elements from two different nativity stories in the Bible, one in Matthew and one in Luke, with a few embellishments that got added in later centuries. What was the historical kernel? Most likely we will never know, because it appears that the Bible’s nativity stories are themselves highly-embellished late add-ons to the Gospels.

Picture a creche with baby Jesus in a manger and shepherds and angels and three kings and a star over the stable roof. We think of this traditional scene as representing the Christmas story, but it actually mixes elements from two different nativity stories in the Bible, one in Matthew and one in Luke, with a few embellishments that got added in later centuries. What was the historical kernel? Most likely we will never know, because it appears that the Bible’s nativity stories are themselves highly-embellished late add-ons to the Gospels.

Here are six hints that the story so familiar to us might have been unfamiliar to early Jesus worshipers.

1. Paul’s Silence –The earliest texts in the New Testament are letters written during the first half of the first century by Paul and other people who used his name. These letters, or Epistles as they are called, give no hint that Paul or the forgers who used his name had heard about any signs and wonders surrounding the birth of Jesus, nor that his mother was a virgin impregnated by God in spirit form. Paul simply says that he was a Jew, born to a woman.

2. Mark’s Silence –The Gospel of Mark—thought to be the earliest of the four gospels and, so, closest to actual events—doesn’t contain a nativity or “infancy” story, even though it otherwise looks to be the primary source document for Matthew and Luke. In Mark, the divinity of Jesus gets established by wonders at the beginning of his ministry, and some Christian sects have believed that he was adopted by God at this point. Why is Mark thought to be where the authors of Matthew and Luke got material? For starters, some passages in Mark, Matthew, and Luke would likely get flagged by plagiarism software. But in the original Greek, Mark is the most primitive and least polished of the three. It also is missing powerful passages like the Sermon on the Mount and has endings that vary from copy to copy. These are some of the reasons that scholars believe it predates the other two. Unlike Paul, the author of Mark was writing a life history of Jesus, one that was full of miracles. It would have been odd for him to simply leave out the auspicious miracles surrounding the birth of Jesus—unless those stories didn’t yet exist.

More here.

Thursday, December 20, 2018

The Ultimate Best Books of 2018 List

Emily Temple in Literary Hub:

It’s mid-December, and likely you are sick and tired of best-of lists. I know, because I am too—especially after reading 52 of them and tracking their contents for the very piece you are reading—so trust me when I say that the monstrosity below is the last best-books-of-2018 list you’ll ever have to read.

It’s mid-December, and likely you are sick and tired of best-of lists. I know, because I am too—especially after reading 52 of them and tracking their contents for the very piece you are reading—so trust me when I say that the monstrosity below is the last best-books-of-2018 list you’ll ever have to read.

To put this together, as I did last year, I looked at all of the end-of-year best books lists I could find online, tallied up their picks, and figured out which individual books were the most often recommended. This year, I counted 52 lists from 37 sources, which added up to a grand total of 880 books. I didn’t include any books from the UK lists, since they often have slightly different publication schedules. I tried my best to balance fiction and nonfiction, but some places only offered one or the other at the time of writing, and the final compilation is probably a little heavy on the fiction side.

So while I’m sure I didn’t get every list, and more are no doubt appearing even as I write this, I feel I can reasonably attest that the books below are the ones that the literary world at large has deemed the “best” of 2018. Does that mean they are actually the best? You’ll have to read them and decide for yourself. But if you’re looking for a relatively sure bet for a gift or some holiday reading, this is a good place to start.

More here.

A History of Cyborg Sex, 2018–73

Cathy O’Neil in the Boston Review:

A lot of people don’t know this, but we once thought cyborg sex might be a bad idea. Back in the 2010s, serious concerns were raised by prominent scholars that sex robots were made by men, for men. The general consensus was that cyborg sex would further support the notion that women’s bodies were available for objectification, sexual gratification, and violence.

A lot of people don’t know this, but we once thought cyborg sex might be a bad idea. Back in the 2010s, serious concerns were raised by prominent scholars that sex robots were made by men, for men. The general consensus was that cyborg sex would further support the notion that women’s bodies were available for objectification, sexual gratification, and violence.

Indeed, in the dawn of sex robots and dolls, the evidence was concerning: we saw hordes of male customers, and the robots were typically created to mimic young, passive sex bimbos. Men were even losing the ability to differentiate between “real” and “robot” wives, and people feared that the advent of robot lovers would further create asymmetry in the “marriage market” for women—that women would be confined and pressured into settling for archaic, misogynistic, or even abusive romantic situations.

In short, the advent of cyborg sex was seen as destabilizing, and it was largely expected to tilt the power further toward men.

Now, more than fifty years later, that curious beginning is laughably remote from our current-day relationship with our cyborg lovers, and the evolution of cyborg sex warrants telling.

More here.

The US Poet Laureate examines why and how political poetry is hot again

Tracy K. Smith in the New York Times:

In the mid-1990s, when I was a student of creative writing, there prevailed a quiet but firm admonition to avoid composing political poems. It was too dangerous an undertaking, one likely to result in didacticism and slackened craft. No, in American poetry, politics was the domain of the few and the fearless, poets like Adrienne Rich or Denise Levertov, whose outsize conscience justified such risky behavior. Even so, theirs weren’t the voices being discussed in workshops and craft seminars.

In the mid-1990s, when I was a student of creative writing, there prevailed a quiet but firm admonition to avoid composing political poems. It was too dangerous an undertaking, one likely to result in didacticism and slackened craft. No, in American poetry, politics was the domain of the few and the fearless, poets like Adrienne Rich or Denise Levertov, whose outsize conscience justified such risky behavior. Even so, theirs weren’t the voices being discussed in workshops and craft seminars.

Maybe it was our relative political stability that kept Americans from stepping into the fray. Perhaps America’s individualism predisposed its poets toward the lyric poem, with its insistence on the primacy of a single speaker whose politics were intimate, internal, invisible. Then came the attacks on the World Trade Center in September 2001, and the war in Iraq, and something shifted in the nation’s psyche.

More here.

Sean Carroll’s Mindscape Podcast: Janna Levin on Black Holes, Chaos, and the Narrative of Science

Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

It’s a big universe out there, full of an astonishing variety of questions and puzzles. Today’s guest, Janna Levin, is a physicist who has delved into some of the trippiest aspects of cosmology and gravitation: the topology of the universe, extra dimensions of space, and the appearance of chaos in orbits around black holes. At the same time, she has been a pioneer in talking about science in interesting and innovative ways: a personal memoir, a novelized narrative of famous scientific lives, and a journalistic exploration of one of the most important experiments of our time. We talk about how one shapes an unusual scientific career, and how the practice of science relates to more traditionally humanistic concerns.

It’s a big universe out there, full of an astonishing variety of questions and puzzles. Today’s guest, Janna Levin, is a physicist who has delved into some of the trippiest aspects of cosmology and gravitation: the topology of the universe, extra dimensions of space, and the appearance of chaos in orbits around black holes. At the same time, she has been a pioneer in talking about science in interesting and innovative ways: a personal memoir, a novelized narrative of famous scientific lives, and a journalistic exploration of one of the most important experiments of our time. We talk about how one shapes an unusual scientific career, and how the practice of science relates to more traditionally humanistic concerns.

More here.

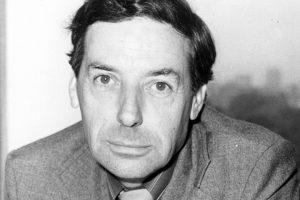

Bernard Williams: Ethics from a Human Point of View

Paul Russell at the TLS:

In an interview that he gave near the end of his life, Williams says that most of his efforts in philosophy are focused on this point: “to make some sense of the ethical as opposed to throwing out the whole thing because you can’t have an idealized version” (Williams’s emphasis). He pursues this fundamental theme by way of his two-sided critique of what he calls “the morality system”. It is two-sided because not only does it aim to discredit the forms of “idealization” that the morality system has encouraged, it also seeks to provide an account of what we are left with when we discard or abandon its assumptions and aspirations. His central text for this programme is Ethics and the Limits of Philosophy (1985). Understood this way, Ethics and the Limits of Philosophy constitutes Williams’s pivotal work, in part because it is his most ambitious and wide-ranging. Beyond that, however, Ethics and the Limits of Philosophy both brings together the diverse threads and strands of his earlier work – much of which is critical in character – and lays the foundation for his later work, particularly his last two books: Shame and Necessity (1993) and Truth and Truthfulness (2002). All these contributions “hang together” (to use Williams’s own expression). In the final analysis, it is not possible to have a complete understanding of the central concerns of Williams’s philosophy without putting Ethics and the Limits of Philosophy at the heart of it.

more here.

Thursday Poem

Writers Are My Nepenthe

—with apologies to Ted Joans

Writers are my nepenthe. They alone saved my soul more akin to

peyote than some mundane substance. The best kind of therapy.

Workshops and journals get holy sometimes. My jones gets going.

They are sanctified stages. But other places are like certain com-

mercial hospitals (where bloods are sold). I don’t dig their evange-

lists. I be on the side of the free but don’t come cheap. Ain’t into no

slave labor. Writing is still my nepenthe. Makes me feel better

’cause I hear the messengers. From: the right reverend amiri/seer

sonia/sister sandra maria/the wizard wonder/uncle etheridge/cler-

ic rakim/minister morrison/saviour sekou/baba john/deacon diva

lisa/empress erykah/rector victor cruz/zoastrian zora hurston/trix-

ter darius/freemason mosley/fundamentalist yusef/priestess pat

landrum/heirophant hattie gossett/holy roller nona hendrix/ecu-

menical ethelbert/monkess jayne cortez/guru babs

gonzalez/preacher quincy/his funkness formerly known as/deacon

steve cannon/ and sunday teacher ted joans/they let me lay my

burden low. they are the runaway from which I go! yeah, so, writers

are my nepenthe. Writers are….

by Tracie Morris

from: Intermission

Soft Skull Press, 1998

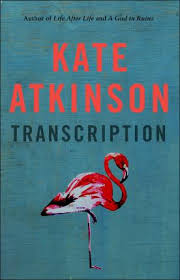

A Girl, Undaunted

Patricia Craig at The Dublin Review of Books:

This is a novel about double-dealing, about honourable and dishonourable forms of duplicity, about multiple impersonations, about lies and secrets and their ultimate consequences. Juliet is soon provided with an alternative identity ‑ Iris Carter-Jenkins is her bogus name ‑ and sent to infiltrate a fascist organisation known as the Right Club. This club holds its meetings in a flat above a cafe in South Kensington called the Russian Tea Rooms, which is run by an Admiral Wolkoff and his daughter Anna. The young transcriber has been upgraded to a full-blown MI5 agent, and adopts a mettlesome personality to go with her new role. “She had already decided that Iris Carter-Jenkins was a gutsy kind of girl.” Gutsy enough to carry a small gun in her handbag, and keep her nerve in the face of imminent unmasking.

This is a novel about double-dealing, about honourable and dishonourable forms of duplicity, about multiple impersonations, about lies and secrets and their ultimate consequences. Juliet is soon provided with an alternative identity ‑ Iris Carter-Jenkins is her bogus name ‑ and sent to infiltrate a fascist organisation known as the Right Club. This club holds its meetings in a flat above a cafe in South Kensington called the Russian Tea Rooms, which is run by an Admiral Wolkoff and his daughter Anna. The young transcriber has been upgraded to a full-blown MI5 agent, and adopts a mettlesome personality to go with her new role. “She had already decided that Iris Carter-Jenkins was a gutsy kind of girl.” Gutsy enough to carry a small gun in her handbag, and keep her nerve in the face of imminent unmasking.

There’s a touch of high jinks about Juliet’s anti-Right-Club activities, and indeed about all her doings at this point, not excluding her romantic interest in her mentor Perry Gibbons, whom she fails to suspect of homosexual leanings, even when these are paraded under her nose. She feels at times as if she’s been caught up in “a Girls’ Own adventure” (actually, a Schoolfriend adventure would be nearer the mark; the Girls’ Own Paper was a rather staid publication); and Buchan and Erskine Childers are never far from her thoughts.

more here.

John Akomfrah, On the Verge

Tiana Reed at The Paris Review:

I first saw an Akomfrah film before I knew it was an Akomfrah film. I remember watching the documentary Seven Songs for Malcolm X (1993) in my single dorm room at the top of a hill on McGill’s campus in Montreal. I was alone in college, surrounded by people, and had settled into a life of solemnity. My first laptop had a disc drive, and I had gotten into the habit of borrowing DVDs from the university library in a forlorn attempt to stay in at least one night on the weekends. I, like my father, had gone through a phase contemplating conversion to Islam. Converting from what, I never knew. I didn’t take it as seriously as he did (I never went to mosque), and mostly I just crushed on the hero, who I referred to in the margins of his autobiography as “Mal.” (Unlike my entrepreneurial Jamaican father, I had confused wanting to be a black Muslim with wanting to be a black Marxist.)

I first saw an Akomfrah film before I knew it was an Akomfrah film. I remember watching the documentary Seven Songs for Malcolm X (1993) in my single dorm room at the top of a hill on McGill’s campus in Montreal. I was alone in college, surrounded by people, and had settled into a life of solemnity. My first laptop had a disc drive, and I had gotten into the habit of borrowing DVDs from the university library in a forlorn attempt to stay in at least one night on the weekends. I, like my father, had gone through a phase contemplating conversion to Islam. Converting from what, I never knew. I didn’t take it as seriously as he did (I never went to mosque), and mostly I just crushed on the hero, who I referred to in the margins of his autobiography as “Mal.” (Unlike my entrepreneurial Jamaican father, I had confused wanting to be a black Muslim with wanting to be a black Marxist.)

Whatever I wanted to be, I could dream up. Whatever I was, I did not know. In Seven Songs for Malcolm X—which features interviews with Betty Shabazz, Spike Lee, Robin D. G. Kelley, and others—the activist Yuri Kochiyama recalls the hours before Malcolm X was assassinated at the Audubon Ballroom in New York City: “There was something in the air, I wouldn’t know how to pinpoint it, but there seemed to be a lot of anxiety.”

more here.

Iron Is the New Cholesterol

Clayton Dalton in Nautilus:

The story of energy metabolism—the basic engine of life at the cellular level—is one of electrons flowing much like water flows from mountains to the sea. Our cells can make use of this flow by regulating how these electrons travel, and by harvesting energy from them as they do so. The whole set-up is really not so unlike a hydroelectric dam. The sea toward which these electrons flow is oxygen, and for most of life on earth, iron is the river. (Octopuses are strange outliers here—they use copper instead of iron, which makes their blood greenish-blue rather than red). Oxygen is hungry for electrons, making it an ideal destination. The proteins that facilitate the delivery contain tiny cores of iron, which manage the handling of the electrons as they are shuttled toward oxygen.

The story of energy metabolism—the basic engine of life at the cellular level—is one of electrons flowing much like water flows from mountains to the sea. Our cells can make use of this flow by regulating how these electrons travel, and by harvesting energy from them as they do so. The whole set-up is really not so unlike a hydroelectric dam. The sea toward which these electrons flow is oxygen, and for most of life on earth, iron is the river. (Octopuses are strange outliers here—they use copper instead of iron, which makes their blood greenish-blue rather than red). Oxygen is hungry for electrons, making it an ideal destination. The proteins that facilitate the delivery contain tiny cores of iron, which manage the handling of the electrons as they are shuttled toward oxygen.

This is why iron and oxygen are both essential for life. There is a dark side to this cellular idyll, though.

Normal energy metabolism in cells produces low levels of toxic byproducts. One of these byproducts is a derivative of oxygen called superoxide. Luckily, cells contain several enzymes that clean up most of this leaked superoxide almost immediately. They do so by converting it into another intermediary called hydrogen peroxide, which you might have in your medicine cabinet for treating nicks and scrapes. The hydrogen peroxide is then detoxified into water and oxygen. Things can go awry if either superoxide or hydrogen peroxide happen to meet some iron on the way to detoxification. What then happens is a set of chemical reactions (described by Haber-Weiss chemistry and Fenton chemistry) that produce a potent and reactive oxygen derivative known as the hydroxyl radical. This radical—also called a free radical—wreaks havoc on biological molecules everywhere. As the chemists Barry Halliwell and John Gutteridge—who wrote the book on iron biochemistry—put it, “the reactivity of the hydroxyl radicals is so great that, if they are formed in living systems, they will react immediately with whatever biological molecule is in their vicinity, producing secondary radicals of variable reactivity.”

Such is the Faustian bargain that has been struck by life on this planet. Oxygen and iron are essential for the production of energy, but may also conspire to destroy the delicate order of our cells. As the neuroscientist J.R. Connor has said, “life was designed to exist at the very interface between iron sufficiency and deficiency.”

More here.

Human Nature is Here to Stay

Larry Arnhart in The New Atlantis:

In the first issue of The New Atlantis, Leon Kass suggests that if biotechnology were to transform human nature, it would do so to satisfy the human dream of physical and mental perfection — “ageless bodies, happy souls.” But how likely is that? As an indication of what he foresees, Kass says that with drugs, “we can eliminate psychic distress, we can produce states of transient euphoria, and we can engineer more permanent conditions of good cheer, optimism, and contentment.” He refers to those “powerful yet seemingly safe anti-depressant and mood brighteners like Prozac, capable in some people of utterly changing their outlook on life from that of Eeyore to that of Mary Poppins.” Similarly, psychiatrist Peter Kramer — in his best-selling book Listening to Prozac — described patients using Prozac who were not just cured of depression but so transformed in their personalities as to be “better than well.” Shy, quiet people were apparently turned into ebullient and socially engaging people. “Like Garrison Keillor’s marvelous Powdermilk biscuits,” Kramer observed, “Prozac gives these patients the courage to do what needs to be done.” This was the beginning, he concluded, of “cosmetic psychopharmacology,” by which people could use chemicals to take on whatever personality they might prefer.

In the first issue of The New Atlantis, Leon Kass suggests that if biotechnology were to transform human nature, it would do so to satisfy the human dream of physical and mental perfection — “ageless bodies, happy souls.” But how likely is that? As an indication of what he foresees, Kass says that with drugs, “we can eliminate psychic distress, we can produce states of transient euphoria, and we can engineer more permanent conditions of good cheer, optimism, and contentment.” He refers to those “powerful yet seemingly safe anti-depressant and mood brighteners like Prozac, capable in some people of utterly changing their outlook on life from that of Eeyore to that of Mary Poppins.” Similarly, psychiatrist Peter Kramer — in his best-selling book Listening to Prozac — described patients using Prozac who were not just cured of depression but so transformed in their personalities as to be “better than well.” Shy, quiet people were apparently turned into ebullient and socially engaging people. “Like Garrison Keillor’s marvelous Powdermilk biscuits,” Kramer observed, “Prozac gives these patients the courage to do what needs to be done.” This was the beginning, he concluded, of “cosmetic psychopharmacology,” by which people could use chemicals to take on whatever personality they might prefer.

But as even Kramer has conceded, this chemical transformation in personality appears to work well in only a minority of the people taking Prozac. And in recent years, there have been increasing reports of many harmful side effects. This is to be expected, because like all psychotropic drugs, Prozac disrupts the normal functioning of the brain, and the brain responds by countering the effect of the drug, which then induces harmful distortions in the neural system. Specifically, Prozac blocks the normal removal of the neurotransmitter serotonin from the space between nerve cells. This creates an overabundance of serotonin, and the brain responds either by reducing receptivity to serotonin or by reducing the production of serotonin. As a result, the brain creates an imbalance in response to the disruption of the drug and cannot function normally. There is also growing evidence that Prozac does not really cure depression. Many studies have shown that the antidepressant effects of taking Prozac are not much greater than what occurs when people take a placebo pill.

But the most fundamental problem with Prozac is one that it shares with all psychotropic drugs (including old-fashioned ones like alcohol). Emotional suffering is a capacity of human nature shaped by evolutionary history for an adaptive purpose. Emotional suffering is almost always a signal that something is wrong in our lives. It alerts us that there is some problem either in our internal lives, in our social relationships, or in our external circumstances. A psychotropic drug does not help us to understand or solve the problem. Rather, the drug deadens the emotional response of our brain without changing the problem that provoked the emotional response in the first place. When we feel bad because of a problem in our lives, taking a psychotropic drug to make us feel better is evasive and self-defeating.

More here. (Note: From the Summer 2003 issue)

Wednesday, December 19, 2018

Who decides what words mean

Lane Greene in Aeon:

Decades before the rise of social media, polarisation plagued discussions about language. By and large, it still does. Everyone who cares about the topic is officially required to take one of two stances. Either you smugly preen about the mistakes you find abhorrent – this makes you a so-called prescriptivist – or you show off your knowledge of language change, and poke holes in the prescriptivists’ facts – this makes you a descriptivist. Group membership is mandatory, and the two are mutually exclusive.

Decades before the rise of social media, polarisation plagued discussions about language. By and large, it still does. Everyone who cares about the topic is officially required to take one of two stances. Either you smugly preen about the mistakes you find abhorrent – this makes you a so-called prescriptivist – or you show off your knowledge of language change, and poke holes in the prescriptivists’ facts – this makes you a descriptivist. Group membership is mandatory, and the two are mutually exclusive.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. I have two roles at my workplace: I am an editor and a language columnist. These two jobs more or less require me to be both a prescriptivist and a descriptivist. When people file me copy that has mistakes of grammar or mechanics, I fix them (as well as applying The Economist’s house style). But when it comes time to write my column, I study the weird mess of real language; rather than being a scold about this or that mistake, I try to teach myself (and so the reader) something new. Is this a split personality, or can the two be reconciled into a coherent philosophy? I believe they can.

More here.

USA ranked 27th in the world in education and healthcare—down from 6th in 1990

Scotty Hendricks in Big Think:

The concept of human capital has only been around since the ’50s but it’s become an increasingly popular way of looking at the economic potential of countries. Typically defined as “the attributes of a population that, along with physical capital such as buildings, equipment, and other tangible assets, contribute to economic productivity” it includes things such as education levels, skill sets, and other intangible items that foster economic growth.

The concept of human capital has only been around since the ’50s but it’s become an increasingly popular way of looking at the economic potential of countries. Typically defined as “the attributes of a population that, along with physical capital such as buildings, equipment, and other tangible assets, contribute to economic productivity” it includes things such as education levels, skill sets, and other intangible items that foster economic growth.

While we already know that a countries’ average education level is associated with its economic growth, a recent study looking into the growth of human capital around the world over the last 26 years has included healthcare outcomes to the mix. While it was created to help motivate lower and middle income countries to increase their human capital investment, it offers a harsh look at the progress the United States has made over the previous 20; if any.

More here.

The Divide Between Silicon Valley and Washington Is a National-Security Threat

Amy Zegart and Kevin Childs in The Atlantic:

A silent divide is weakening America’s national security, and it has nothing to do with President Donald Trump or party polarization. It’s the growing gulf between the tech community in Silicon Valley and the policy-making community in Washington.

Beyond all the acrimonious headlines, Democrats and Republicans share a growing alarm over the return of great-power conflict. China and Russia are challenging American interests, alliances, and values—through territorial aggression; strong-arm tactics and unfair practices in global trade; cyber theft and information warfare; and massive military buildups in new weapons systems such as Russia’s “Satan 2” nuclear long-range missile, China’s autonomous weapons, and satellite-killing capabilities to destroy our communications and imagery systems in space. Since Trump took office, huge bipartisan majorities in Congress have passed tough sanctions against Russia, sweeping reforms to scrutinize and block Chinese investments in sensitive American technology industries, and record defense-budget increases. You know something’s big when senators like the liberal Ron Wyden and the conservative John Cornyn start agreeing.

In Washington, alarm bells are ringing. Here in Silicon Valley, not so much.

More here.