by Anitra Pavlico

For millennia, humans have had a tradition of introspection and meditation. The Buddhist Dhammapada says that when a monk goes into an “empty place” and calms his mind, he experiences “a delight that transcends that of men.” The ancient Greeks exhorted one to know thyself. Montaigne wrote that the “solitude that I love and advocate is chiefly a matter of drawing my feelings and thoughts back into myself.” This was not so easy even in quieter times, but in the wired era, it has become almost impossible. When Bertrand Russell wrote his essay “In Praise of Idleness” in 1932, the threat to downtime and self-fulfillment was work: “I want to say, in all seriousness, that a great deal of harm is being done in the modern world by belief in the virtuousness of work, and that the road to happiness and prosperity lies in an organized diminution of work.” This is still valid, as we work more than ever despite skyrocketing productivity thanks to technological advances. The trouble today, however, is that even our supposed leisure hours are spent on the grid, essentially ensuring that we never get a moment’s rest.

Over the past few years, numerous books and articles have sounded the alarm on how our online habits are affecting our mental health. Even individuals in the tech industry–including Tim Cook, the Apple CEO who prefers that his nephew not use social media, and Tristan Harris, former Google employee and founder of Time Well Spent, a group advocating for more sensible use of online tools—are joining the chorus. Against this backdrop, physicist, novelist, and essayist Alan Lightman has added his own manifesto, In Praise of Wasting Time. Of course, the title is ironic, because Lightman argues that by putting down our devices and spending time on quiet reflection, we regain some of our lost humanity, peace of mind, and capacity for creativity—not a waste of time, after all, despite the prevailing mentality that we should spend every moment actually doing something. The problem is not only our devices, the internet, and social media. Lightman argues that the world has become much more noisy, fast-paced, and distracting. Partly, he writes, this is because the advances that have enabled the much greater transfer of data, and therefore productivity, have created an environment in which seemingly inexorable market forces push for more time working and less leisure time. Read more »

On the morning of August 20, 1968, the Czech playwright Vaclav Havel had a serious hangover. He was at his country home in Liberec after a night of boozing it up with his actor friend

On the morning of August 20, 1968, the Czech playwright Vaclav Havel had a serious hangover. He was at his country home in Liberec after a night of boozing it up with his actor friend  My wife and I took a peek into the interior of Papua New Guinea twenty years ago.

My wife and I took a peek into the interior of Papua New Guinea twenty years ago.

When contemporary atheists criticise religious beliefs, they usually criticise beliefs that only crude religious thinkers embrace. Or so some people claim. The beliefs of the sophisticated religious believer, it’s suggested, are immune to such assaults.

When contemporary atheists criticise religious beliefs, they usually criticise beliefs that only crude religious thinkers embrace. Or so some people claim. The beliefs of the sophisticated religious believer, it’s suggested, are immune to such assaults. Recently I’ve been experimenting with mood-modification through temperature extremes (like

Recently I’ve been experimenting with mood-modification through temperature extremes (like  The state in polities broadly described as ‘liberal democracies’ with political economies broadly described as ‘capitalist’ are characterised by a feature that Gramsci called ‘hegemony’. This is a technical term, not to be confused with the loose use of that term to connote ‘power and domination over another’. In Gramsci’s special sense, hegemony means that a class gets to be the ruling class by convincing all other classes that its interests are the interests of all other classes. It is because of this feature that such states avoid being authoritarian. Authoritarian states need to be authoritarian precisely because they lack Gramscian hegemony. It would follow from this that if a state that does possess hegemony in this sense is authoritarian, there is something compulsive about its authoritarianism. Now, what is interesting is that the present government in India keeps boastfully proclaiming that it possesses hegemony in this sense, that it has all the classes convinced that its policies are to their benefit. If so, one can only conclude that its widely recorded authoritarianism, therefore, is pathological.

The state in polities broadly described as ‘liberal democracies’ with political economies broadly described as ‘capitalist’ are characterised by a feature that Gramsci called ‘hegemony’. This is a technical term, not to be confused with the loose use of that term to connote ‘power and domination over another’. In Gramsci’s special sense, hegemony means that a class gets to be the ruling class by convincing all other classes that its interests are the interests of all other classes. It is because of this feature that such states avoid being authoritarian. Authoritarian states need to be authoritarian precisely because they lack Gramscian hegemony. It would follow from this that if a state that does possess hegemony in this sense is authoritarian, there is something compulsive about its authoritarianism. Now, what is interesting is that the present government in India keeps boastfully proclaiming that it possesses hegemony in this sense, that it has all the classes convinced that its policies are to their benefit. If so, one can only conclude that its widely recorded authoritarianism, therefore, is pathological. So it’s 2018, and we’re at a pivotal point in the world of cancer. A breakthrough has been made, is this the revolution we’ve all been waiting for. Is the cut and burn era over?

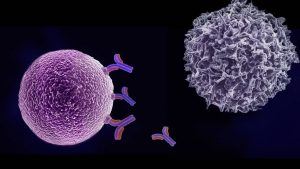

So it’s 2018, and we’re at a pivotal point in the world of cancer. A breakthrough has been made, is this the revolution we’ve all been waiting for. Is the cut and burn era over?

IN MARCH

IN MARCH According to the UK’s

According to the UK’s  American stories trace the sweep of history, but their details are definingly particular. In the summer of 1979, Elizabeth Anderson, then a rising junior at Swarthmore College, got a job as a bookkeeper at a bank in Harvard Square. Every morning, she and the other bookkeepers would process a large stack of bounced checks. Businesses usually had two accounts, one for payroll and the other for costs and supplies. When companies were short of funds, Anderson noticed, they would always bounce their payroll checks. It made a cynical kind of sense: a worker who was owed money wouldn’t go anywhere, or could be replaced, while an unpaid supplier would stop supplying. Still, Anderson found it disturbing that businesses would write employees phony checks, burdening them with bounce fees. It appeared to happen all the time.

American stories trace the sweep of history, but their details are definingly particular. In the summer of 1979, Elizabeth Anderson, then a rising junior at Swarthmore College, got a job as a bookkeeper at a bank in Harvard Square. Every morning, she and the other bookkeepers would process a large stack of bounced checks. Businesses usually had two accounts, one for payroll and the other for costs and supplies. When companies were short of funds, Anderson noticed, they would always bounce their payroll checks. It made a cynical kind of sense: a worker who was owed money wouldn’t go anywhere, or could be replaced, while an unpaid supplier would stop supplying. Still, Anderson found it disturbing that businesses would write employees phony checks, burdening them with bounce fees. It appeared to happen all the time. This past week, Dr. Mark Green, M.D., who was recently elected to the U.S. House of Representatives from the state of Tennessee declared: “Let me say this about

This past week, Dr. Mark Green, M.D., who was recently elected to the U.S. House of Representatives from the state of Tennessee declared: “Let me say this about  The demand that we

The demand that we  Look around on your next plane trip. The iPad is the new pacifier for babies and toddlers. Younger school-aged children read stories on smartphones; older boys don’t read at all, but hunch over video games. Parents and other passengers read on Kindles or skim a flotilla of email and news feeds. Unbeknownst to most of us, an invisible, game-changing transformation links everyone in this picture: the neuronal circuit that underlies the brain’s ability to read is subtly, rapidly changing – a change with implications for everyone from the pre-reading toddler to the expert adult.

Look around on your next plane trip. The iPad is the new pacifier for babies and toddlers. Younger school-aged children read stories on smartphones; older boys don’t read at all, but hunch over video games. Parents and other passengers read on Kindles or skim a flotilla of email and news feeds. Unbeknownst to most of us, an invisible, game-changing transformation links everyone in this picture: the neuronal circuit that underlies the brain’s ability to read is subtly, rapidly changing – a change with implications for everyone from the pre-reading toddler to the expert adult.