Marshall Cohen in The LA Review of Books:

Marshall Cohen in The LA Review of Books:

THE BOUNTIFULLY GIFTED Stanley Cavell was unique among American philosophers of his generation in the range of his philosophical, cultural, and artistic interests. He resisted the split between Anglophone and Continental traditions that has characterized post-Kantian philosophy, writing with distinction about epistemology and aesthetics, Emerson and Thoreau, Shakespearean tragedy and Hollywood comedy, as well as about modernism in film and music. Modernist works, he believed, divide audiences into insiders and outsiders, create unpleasant cults, and demand for their reception the shock of conversion. Such works are not easily received, as Cavell, who regarded himself as a modernist writer, painfully discovered. Many features of his writing have been found troublesome and even offensive by a significant number of readers. I believe these features are not an expression of modernist impulses but rather manifestations of personal idiosyncrasies that Cavell’s autobiographical reflections, in his 2010 book, Little Did I Know: Excerpts from Memory, can help us to understand, if not accept.

Little Did I Know obeys a double time scheme. It comprises a series of entries presented in their order of composition from July 2, 2003, to September 1, 2004. The depicted events reporting Cavell’s Emersonian journey occur in loose chronological order, interrupted by philosophical meditations, portraits of friends, and editorial comments about the original drafted entries. The formal arrangement honors the fundamental importance granted to the time and context of utterance in the work of J. L. Austin and the late Wittgenstein. The depictions allow Cavell to exploit techniques reminiscent of psychoanalysis (free association) and film (flashbacks and flash forwards, jump cuts, close-ups, and montage). And modernism’s experimental departures from traditional narrative facilitate his representation of philosophy as an abstraction of biography.

More here.

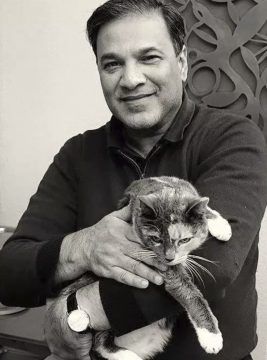

In this episode Fred Weibull interviewed Abbas to learn about the origins and intentions of 3QD, the reasons behind its extraordinary commitment to public service and the emphasis on the art of curation over content production. Abbas expands on 3QD’s process of locating and discerning content, about the organisation of the editorial team, scattered across the world and the particular work discipline and practices of a skilled curator…

In this episode Fred Weibull interviewed Abbas to learn about the origins and intentions of 3QD, the reasons behind its extraordinary commitment to public service and the emphasis on the art of curation over content production. Abbas expands on 3QD’s process of locating and discerning content, about the organisation of the editorial team, scattered across the world and the particular work discipline and practices of a skilled curator…

Marshall Cohen in The LA Review of Books:

Marshall Cohen in The LA Review of Books: The Wake has been called “the most colossal leg pull in literature” and even Joyce’s patron fell out with him over it. But Wake scholarship is thriving more than ever. In the words of Joyce Scholar Sam Slote almost “any analysis will be incomplete.” After Ulysses, Joyce was interested in the subconscious interior monologue, our dreaming lives. He also wanted to shatter the conventions of language to form an almost eternal every-language. It sounds somewhat like the dial of a radio in Joyce’s time, static turning into myriad languages. Joyce intentionally made passages more obscure to evoke radio. PHD candidate Yuta Imazeki has calculated “numbers of portmanteaux and foreign words in the radio passage” that are higher in frequency than any others; intentionally obscure. So is it an indecipherable ruse or a harbinger of hypertext? Could it even be… therapeutic? As a self-taught enthusiast, how did I even get into this?

The Wake has been called “the most colossal leg pull in literature” and even Joyce’s patron fell out with him over it. But Wake scholarship is thriving more than ever. In the words of Joyce Scholar Sam Slote almost “any analysis will be incomplete.” After Ulysses, Joyce was interested in the subconscious interior monologue, our dreaming lives. He also wanted to shatter the conventions of language to form an almost eternal every-language. It sounds somewhat like the dial of a radio in Joyce’s time, static turning into myriad languages. Joyce intentionally made passages more obscure to evoke radio. PHD candidate Yuta Imazeki has calculated “numbers of portmanteaux and foreign words in the radio passage” that are higher in frequency than any others; intentionally obscure. So is it an indecipherable ruse or a harbinger of hypertext? Could it even be… therapeutic? As a self-taught enthusiast, how did I even get into this? IN 1997

IN 1997 He was, to be sure, one of those candles that burn twice as bright but half as long, an all-American violinist in an age dominated by the European virtuoso. He was born on this date in 1936, into a highly musical Manhattan family, his father a violinist in the New York Philharmonic, his mother a piano teacher who had studied at Juilliard. At the age of three, Rabin demonstrated perfect pitch, and soon he was taking piano lessons with his mother, a larger-than-life figure whose Olympian standards were exceeded only by her work ethic and drive. Anthony Feinstein writes in his biography of the violinist that the “force of her character demanded obedience and gratitude. She was unable to brook dissent, and displayed a ruthlessness when it came to enforcing her will.” She had lost her first son, who had shown great promise as a pianist, to scarlet fever, and perhaps because of this, she was all the more determined to make something of her younger son’s talent. Her demands, Feinstein writes, were clear: “the relentless pursuit of excellence, the drive for perfection, the expectation of long, exhausting hours dedicated to practicing music.”

He was, to be sure, one of those candles that burn twice as bright but half as long, an all-American violinist in an age dominated by the European virtuoso. He was born on this date in 1936, into a highly musical Manhattan family, his father a violinist in the New York Philharmonic, his mother a piano teacher who had studied at Juilliard. At the age of three, Rabin demonstrated perfect pitch, and soon he was taking piano lessons with his mother, a larger-than-life figure whose Olympian standards were exceeded only by her work ethic and drive. Anthony Feinstein writes in his biography of the violinist that the “force of her character demanded obedience and gratitude. She was unable to brook dissent, and displayed a ruthlessness when it came to enforcing her will.” She had lost her first son, who had shown great promise as a pianist, to scarlet fever, and perhaps because of this, she was all the more determined to make something of her younger son’s talent. Her demands, Feinstein writes, were clear: “the relentless pursuit of excellence, the drive for perfection, the expectation of long, exhausting hours dedicated to practicing music.” Director-documentarian-deity

Director-documentarian-deity

Nils Lonberg, a scientist at the center of a revolution in cancer therapy, has had a career full of fateful decisions. One of the most crucial: buying an entire bottle of whiskey at a hotel bar.

Nils Lonberg, a scientist at the center of a revolution in cancer therapy, has had a career full of fateful decisions. One of the most crucial: buying an entire bottle of whiskey at a hotel bar. Last November Chinese scientist He Jiankui announced the birth of twin babies whose germline he claimed to have altered to reduce their susceptibility to contracting HIV. The news of embryo editing and gene-edited babies prompted immediate condemnation both within and beyond the scientific community. An ABC News headline asked: “Genetically edited babies—scientific advancement or playing God?”

Last November Chinese scientist He Jiankui announced the birth of twin babies whose germline he claimed to have altered to reduce their susceptibility to contracting HIV. The news of embryo editing and gene-edited babies prompted immediate condemnation both within and beyond the scientific community. An ABC News headline asked: “Genetically edited babies—scientific advancement or playing God?”

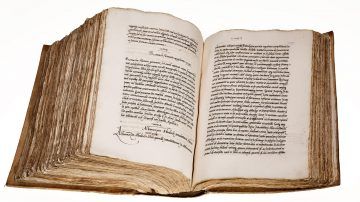

It’s the stuff of a Hollywood blockbuster: Five hundred years ago, a son of Christopher Columbus assembled one of the greatest libraries the world has ever known. The volumes inside were mostly lost to history. Now, a precious book summarizing the contents of the library has turned up in a manuscript collection in Denmark.

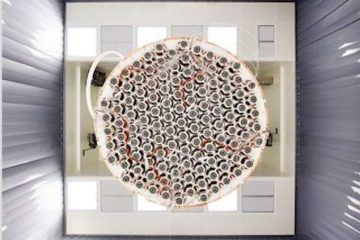

It’s the stuff of a Hollywood blockbuster: Five hundred years ago, a son of Christopher Columbus assembled one of the greatest libraries the world has ever known. The volumes inside were mostly lost to history. Now, a precious book summarizing the contents of the library has turned up in a manuscript collection in Denmark. How do you observe a process that takes more than one trillion times longer than the age of the universe? The XENON Collaboration research team did it with an instrument built to find the most elusive particle in the universe—dark matter. In a paper to be published tomorrow in the journal Nature, researchers announce that they have observed the radioactive decay of xenon-124, which has a half-life of 1.8 X 1022 years.

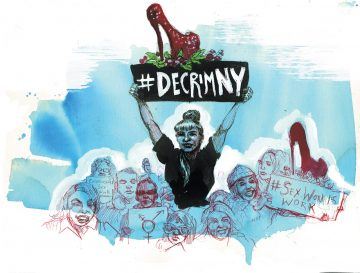

How do you observe a process that takes more than one trillion times longer than the age of the universe? The XENON Collaboration research team did it with an instrument built to find the most elusive particle in the universe—dark matter. In a paper to be published tomorrow in the journal Nature, researchers announce that they have observed the radioactive decay of xenon-124, which has a half-life of 1.8 X 1022 years. For more than 30 years, the critic Camille Paglia has taught at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia. Now a faction of art-school censors wants her fired for sharing wrong opinions on matters of sex, gender identity, and sexual assault.

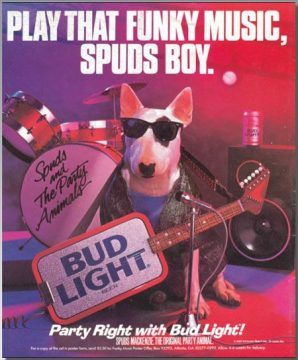

For more than 30 years, the critic Camille Paglia has taught at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia. Now a faction of art-school censors wants her fired for sharing wrong opinions on matters of sex, gender identity, and sexual assault. For a concrete demonstration, consider comedian Yakov Smirnoff, careening at Spuds Factor 10. Today, Smirnoff’s cultural activities have largely been quarantined to the town of

For a concrete demonstration, consider comedian Yakov Smirnoff, careening at Spuds Factor 10. Today, Smirnoff’s cultural activities have largely been quarantined to the town of