[Thanks to Yohan John.]

Category: Recommended Reading

For Love or Money? The Merits of Investing in Art

Andrew Bailey at The Easel:

Looking at this market through the eyes of an investor, what can art offer? Like, say, real estate, it boasts strong capital gains over the longer term. Of the 600% growth in turnover since 1990, price escalation has been a major contributor, albeit skewed toward higher priced works. Advocates say that returns on art investments are uncorrelated with the returns from other asset classes, making it attractive for inclusion in a diversified portfolio. Art is both durable and highly mobile. Various airports in Europe and elsewhere host tax free storage zones where valuable artworks can be held. If a painting quietly changes hands and moves from one storage suite to another, who is to know? Individuals unhappy with their tax bills or nervous about their spouse’s divorce lawyers have been known to exploit these characteristics to great effect. And, of course, art emphatically offers aesthetic returns – it looks great on the living room walls while you await the capital gains.

Looking at this market through the eyes of an investor, what can art offer? Like, say, real estate, it boasts strong capital gains over the longer term. Of the 600% growth in turnover since 1990, price escalation has been a major contributor, albeit skewed toward higher priced works. Advocates say that returns on art investments are uncorrelated with the returns from other asset classes, making it attractive for inclusion in a diversified portfolio. Art is both durable and highly mobile. Various airports in Europe and elsewhere host tax free storage zones where valuable artworks can be held. If a painting quietly changes hands and moves from one storage suite to another, who is to know? Individuals unhappy with their tax bills or nervous about their spouse’s divorce lawyers have been known to exploit these characteristics to great effect. And, of course, art emphatically offers aesthetic returns – it looks great on the living room walls while you await the capital gains.

But art has an Achilles heel – it is difficult to buy and sell. Identifying reputable current artists, knowing what a “fair” price is and who might pay it, understanding a work’s provenance, the risk of forgery, the list goes on and on.

more here.

Sally Wen Mao’s Oculus

Larissa Pham at Poetry Magazine:

Mao was born in Wuhan, China, and moved to the United States at age five. She draws upon her experience of Chinese and Asian American visual culture, which saturates the book with allusions so dense the text requires endnotes. Her landscape is the detritus of television and cinema and internet webcams, the jetstream of the image in an era when most everything has become visual matter. In the aforementioned interview with the Creative Independent, Mao describes the themes at the heart of Oculus: “It’s obsessed with spectacle and being looked at, but it also is aware of all the violence that comes with being looked at.”

Mao was born in Wuhan, China, and moved to the United States at age five. She draws upon her experience of Chinese and Asian American visual culture, which saturates the book with allusions so dense the text requires endnotes. Her landscape is the detritus of television and cinema and internet webcams, the jetstream of the image in an era when most everything has become visual matter. In the aforementioned interview with the Creative Independent, Mao describes the themes at the heart of Oculus: “It’s obsessed with spectacle and being looked at, but it also is aware of all the violence that comes with being looked at.”

“Occidentalism,” a poem early in the book, is a useful guide for how to read the collection. Its subject is the world of text: “A man celebrates erstwhile conquests, / his book locked in a silo, still in print. // I scribble, make Sharpie lines, deface / its text like it defaces me.”

more here.

Life After A Cyclone in Mozambique

Mia Couto at the TLS:

I manage to travel two weeks after the cyclone. The pilot of the plane is a friend and he tells me that he is going to fly over the area around my city so that I can see the extent of the flooding. He’s right to show me: for miles around, the land is sea. Villages and small towns that I would normally recognize are still under water. I regret sitting next to the window. I regret not taking Dany’s advice to cancel my trip. I remember the moment my brothers decided to go to visit the body of my father in the morgue. I refused to go with them. I wanted to find again the living expression and warm hands of the man who gave me life. And once more, I’m torn apart by what I must confront. Beneath me is my decapitated city. I have to wipe my eyes to keep on looking. The other passengers are filming and taking photographs. And all this is unreal to me. I’m the last to leave the plane, as if afraid of not knowing how to walk on that ground, my first ground. As children, we don’t say goodbye to places. We always think that we’ll come back. We believe that it’s never the last time. And that trip had the bitter taste of goodbye.

I manage to travel two weeks after the cyclone. The pilot of the plane is a friend and he tells me that he is going to fly over the area around my city so that I can see the extent of the flooding. He’s right to show me: for miles around, the land is sea. Villages and small towns that I would normally recognize are still under water. I regret sitting next to the window. I regret not taking Dany’s advice to cancel my trip. I remember the moment my brothers decided to go to visit the body of my father in the morgue. I refused to go with them. I wanted to find again the living expression and warm hands of the man who gave me life. And once more, I’m torn apart by what I must confront. Beneath me is my decapitated city. I have to wipe my eyes to keep on looking. The other passengers are filming and taking photographs. And all this is unreal to me. I’m the last to leave the plane, as if afraid of not knowing how to walk on that ground, my first ground. As children, we don’t say goodbye to places. We always think that we’ll come back. We believe that it’s never the last time. And that trip had the bitter taste of goodbye.

more here.

From Susan Sontag to the Met Gala: on the evolution of camp

Jon Savage in The Guardian:

First published in 1964, Susan Sontag’s essay Notes on Camp remains a groundbreaking piece of cultural activism. Sontag’s achievement was to give a name to an aesthetic that was everywhere yet until then had gone largely unremarked. It was visible in Dusty Springfield’s mascara and beehive, there in late-night TV reruns of old Humphrey Bogart movies; there in Andy Warhol’s screen prints Flowers andElectric Chair – images from advertising and the news media copied and provocatively represented. Like pop, camp was the future; as Warhol had observed on his cross-country trip in 1963, it was omnipresent, so ubiquitous that it wasn’t simply an aesthetic. It was an environment, a climate, with profound implications for western culture. To notice it, all you needed was the keen eye of an outsider.

First published in 1964, Susan Sontag’s essay Notes on Camp remains a groundbreaking piece of cultural activism. Sontag’s achievement was to give a name to an aesthetic that was everywhere yet until then had gone largely unremarked. It was visible in Dusty Springfield’s mascara and beehive, there in late-night TV reruns of old Humphrey Bogart movies; there in Andy Warhol’s screen prints Flowers andElectric Chair – images from advertising and the news media copied and provocatively represented. Like pop, camp was the future; as Warhol had observed on his cross-country trip in 1963, it was omnipresent, so ubiquitous that it wasn’t simply an aesthetic. It was an environment, a climate, with profound implications for western culture. To notice it, all you needed was the keen eye of an outsider.

In 58 paragraphs, Sontag conducted an intuitive yet rigorous examination of a phenomenon that she defined as “a badge of identity among small urban cliques”. And this “private code” constituted a new mode of perception that collapsed traditional ideas of high and low culture, of elitism and mass appeal. Here was a new hierarchy of taste, no longer defined by the old gatekeepers. Camp was a “way of seeing the world as an aesthetic phenomenon”, she wrote, “in terms of the degree of artifice, of stylisation”. Sontag’s early passages outline the now overfamiliar “so bad it’s good” aesthetic: it could be found in the drawings of Aubrey Beardsley, the 1933 film King Kong and Tiffany lamps. Today, Sontag’s observations remind us of how objects and works that were déclassé in the 1960s have become part of accepted taste. She predicted this would happen, of course: “The canon of Camp can change. Time has a great deal to do with it. Time may enhance what seems simply dogged or lacking in fantasy now because we are too close to it.”

More here.

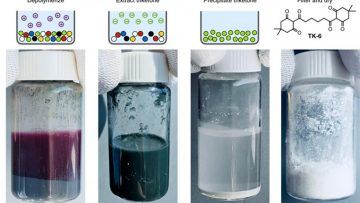

Breakthrough detection can lead to 100 percent recyclable plastic

From vaaju.com:

Plastic pollution in the world’s oceans may have an impact of $ 2.5 billion, adversely affecting “almost all marine ecosystem services”, including areas such as fishing, recreation and heritage. But a breakthrough from researchers at Berkeley Lab may be the solution the planet needs for this eye-opening problem – recyclable plastic. The study, published in Nature Chemistry, describes how the researchers could find a new way to assemble plastic and reuse them “to new materials of any color, shape or shape.” “Most plastic materials were never made to be recycled,” says senior author Peter Christensen, a postdoctoral researcher at Berkeley Lab’s molecular foundry, in the statement. “But we have discovered a new way to assemble plastic that takes into account recycling from a molecular perspective.”

Plastic pollution in the world’s oceans may have an impact of $ 2.5 billion, adversely affecting “almost all marine ecosystem services”, including areas such as fishing, recreation and heritage. But a breakthrough from researchers at Berkeley Lab may be the solution the planet needs for this eye-opening problem – recyclable plastic. The study, published in Nature Chemistry, describes how the researchers could find a new way to assemble plastic and reuse them “to new materials of any color, shape or shape.” “Most plastic materials were never made to be recycled,” says senior author Peter Christensen, a postdoctoral researcher at Berkeley Lab’s molecular foundry, in the statement. “But we have discovered a new way to assemble plastic that takes into account recycling from a molecular perspective.”

Plastic pollution in the world’s oceans may have $ 2.5 TRILLION IMPACT, STUDY SAYS

Known as poly (diketoenamine) or PDK, the new type of plastic material can help stop the tide of plastic as the PDK forms can be reversed via a simple acid bath, the researchers believe. “Poly (diketoenamine) s” clicks “together from a variety of triketones and aromatic or aliphatic amines, giving only water as a by-product,” abstraction of the abstract reads. “Recycled monomers can be transformed into the same polymer formulation without loss of performance, as well as other polymer formulations with differentiated properties. The simplicity with which poly (diketoenamine) s can be made, used, recycled and reused without losing value points to new directions in designing durable polymers with minimal environmental impact. ” Unlike conventional plastic, monomers of PDK plastic could simply be recovered and freed from any added additives simply by dumping the material in a very acidic solution.

More here.

Wednesday, May 8, 2019

A Manifesto for Opting Out of an Internet-Dominated World

Jonah Engel Bromwich in the New York Times:

In 2015, Jenny Odell started an organization she called The Bureau of Suspended Objects. Odell was then an artist-in-residence at a waste operating station in San Francisco. As the sole employee of her bureau, she photographed things that had been thrown out and learned about their histories. (A bird-watcher, Odell is friendly with a pair of crows that sit outside her apartment window; given her talent for scavenging, you wonder whether they’ve shared tips.)

In 2015, Jenny Odell started an organization she called The Bureau of Suspended Objects. Odell was then an artist-in-residence at a waste operating station in San Francisco. As the sole employee of her bureau, she photographed things that had been thrown out and learned about their histories. (A bird-watcher, Odell is friendly with a pair of crows that sit outside her apartment window; given her talent for scavenging, you wonder whether they’ve shared tips.)

Odell’s first book, “How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy,” echoes the approach she took with her bureau, creating a collage (or maybe it’s a compost heap) of ideas about detaching from life online, built out of scraps collected from artists, writers, critics and philosophers. In the book’s first chapter, she remarks that she finds things that already exist “infinitely more interesting than anything I could possibly make.” Then, summoning the ideas of others, she goes on to construct a complex, smart and ambitious book that at first reads like a self-help manual, then blossoms into a wide-ranging political manifesto.

More here.

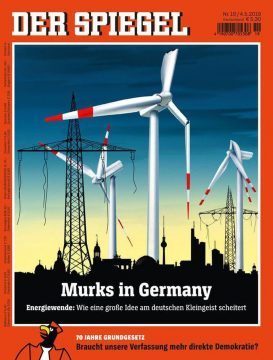

The Reason Renewables Can’t Power Modern Civilization Is Because They Were Never Meant To

Michael Shellenberger in Forbes:

Over the last decade, journalists have held up Germany’s renewables energy transition, the Energiewende, as an environmental model for the world.

Over the last decade, journalists have held up Germany’s renewables energy transition, the Energiewende, as an environmental model for the world.

“Many poor countries, once intent on building coal-fired power plants to bring electricity to their people, are discussing whether they might leapfrog the fossil age and build clean grids from the outset,” thanks to the Energiewende, wrote a New York Times reporter in 2014.

With Germany as inspiration, the United Nations and World Bank poured billions into renewables like wind, solar, and hydro in developing nations like Kenya.

But then, last year, Germany was forced to acknowledge that it had to delay its phase-out of coal, and would not meet its 2020 greenhouse gas reduction commitments. It announced plans to bulldoze an ancient church and forest in order to get at the coal underneath it.

We Need to Talk About Europe

Jason Barker in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

Is anyone free to decide her own destiny? Or is the course of her life determined by prior events? Since so many of our decisions operate under constraints of various kinds — the imperative to do something or be somewhere at a fixed time — is free will an illusion? The question takes on added significance given the overwhelming economic imperative to survive in a vicious world. So much of what we desire nowadays is not so much “unthinkable” — we can always dream — as practically impossible. What hope is there of recovering possibility from a world in which the future has become as predictable as the next rent day?

Is anyone free to decide her own destiny? Or is the course of her life determined by prior events? Since so many of our decisions operate under constraints of various kinds — the imperative to do something or be somewhere at a fixed time — is free will an illusion? The question takes on added significance given the overwhelming economic imperative to survive in a vicious world. So much of what we desire nowadays is not so much “unthinkable” — we can always dream — as practically impossible. What hope is there of recovering possibility from a world in which the future has become as predictable as the next rent day?

Srećko Horvat’s task in his short philosophical work Poetry from the Future is to claw back this lost horizon. Decrying neoliberal capitalism’s “slow cancellation of the future,” Horvat advocates a “hope without optimism” for transcending this bad infinity: a philosophy for the front lines.

More here.

“As I Walked Out One Evening” read by W. H. Auden himself

New Tools Could Help Pin Down the Cause of a Failing Memory

Elizabeth Svoboda and Undark in The Atlantic:

As he neared his 50s, Anthony Andrews realized that living inside his own head felt different than it used to. The signs were subtle at first. “My wife started noticing that I wasn’t getting through things,” Andrews says. Every so often, he’d experience what he calls “cognitive voids,” where he’d get dizzy and blank out for a few seconds. Over time, Andrews’s issues became more pronounced. It wasn’t just that he would lose track of things, as if a thought bubble over his head had popped. A dense calm had descended on him like a weighted blanket. “I felt like I was walking through the swamp,” says Andrews, now 54. He had to play internet chess each morning to penetrate the mental murk.

With his wife, Mona, by his side, Andrews went to doctor after doctor, racking up psychiatric diagnoses. One told him he had ADHD. Another thought he was depressed, and another said he had bipolar disorder. But the drugs and therapies they prescribed didn’t seem to help. “After a month,” Andrews recalls of these treatments, “I knew it’s not for me.” After a few rounds of diagnostic hopscotch, Mona found David Merrill, a psychiatrist and brain researcher at the University of California at Los Angeles. Other doctors had diagnosed Andrews based mostly on his symptoms, but Merrill proposed a new approach: using computer software called Neuroreader to measure the volume of Andrews’s brain. The results were a shock: Based on small volume changes, along with Andrews’s history and cognitive tests, Merrill told Andrews that he likely had chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a neurodegenerative disorder caused by repeated head impacts. Andrews was stunned. CTE? Like Dave Duerson, Junior Seau, and all those other NFL guys? Sure, he’d played football as a kid, but he’d mostly stopped after high school.

What medicine can teach academia about preventing burnout

Kim and Faber in Nature:

Burnout — work-related stress resulting in emotional and physical exhaustion — remains an expected rite of passage for many professions. However, the medical community has begun to place more emphasis on reducing burnout — and science academia would do well to learn from it. Despite the differences between medical and scientific training, stress is a common denominator for students in both fields. For example, in a 2011 survey of graduate students at 26 major US universities, 37% of graduate students in the natural sciences and 41% in engineering or computer science reported experiencing “a bit more” or “a lot more” stress than they felt able to handle. Similarly, a 2010 cross-sectional study found that 52.8% of medical students at 7 US universities had experienced burnout1.

Burnout — work-related stress resulting in emotional and physical exhaustion — remains an expected rite of passage for many professions. However, the medical community has begun to place more emphasis on reducing burnout — and science academia would do well to learn from it. Despite the differences between medical and scientific training, stress is a common denominator for students in both fields. For example, in a 2011 survey of graduate students at 26 major US universities, 37% of graduate students in the natural sciences and 41% in engineering or computer science reported experiencing “a bit more” or “a lot more” stress than they felt able to handle. Similarly, a 2010 cross-sectional study found that 52.8% of medical students at 7 US universities had experienced burnout1.

Graduate students must contend with juggling coursework and research, lack of external validation, perceived devaluation of their work by the public and anxiety over future job prospects. All of these stressors combine to create a toxic environment in which cynicism and pessimism can prevail. Many studies have shown that people who experience stress also experience decreased productivity2 and creativity3, compared with those who feel little or no stress — yet these two traits are key to being a successful scientist.

Graduate programmes can help students to combat burnout. We propose that institutions take the following steps:

1. Enable time away from the lab. In sectors such as the technology industry, flexible work policies have led to more-satisfied, more productive employees4,5. Although working from home or taking time off spontaneously is less feasible in medical and graduate training, some institutions have embraced trainee wellness, allowing students to take absences as needed.

More here.

Podcasting Hell

The Editors at n+1:

Maybe podcasting would be more interesting if it were an instrument of fascism, or terrorism. ISIS knows better: they don’t make podcasts, they make YouTube videos. Talk radio can still control the listener’s emotional response, but no one feels threatened by the infinitely banal podcast. Instead of emotion or camaraderie, what podcasts produce is chumminess — reminiscent of the bourgeois club atmosphere, reconfigured as the desperate friendliness of burned-out knowledge workers. They aren’t pieces of media so much as second jobs or second lives — a way to pursue our hobbies when we have no time to spare, to have smart people talk at us when we have no time to think, to have new books summarized when we have no time to read. Our relationship with podcasts exists in uninterrupted parallel to the rest of our existence, a wealth of knowledge ready to be tapped at any moment. Podcasts intensify our saturation while pretending to relieve it. It’s like a voluntary authoritarian state, except instead of state-funded sitcoms, we have Marc Maron. But what would we do without it? Die, probably. Be murdered. Become a true-crime podcast. Don’t forget us when we’re gone; please rate us on iTunes.

Maybe podcasting would be more interesting if it were an instrument of fascism, or terrorism. ISIS knows better: they don’t make podcasts, they make YouTube videos. Talk radio can still control the listener’s emotional response, but no one feels threatened by the infinitely banal podcast. Instead of emotion or camaraderie, what podcasts produce is chumminess — reminiscent of the bourgeois club atmosphere, reconfigured as the desperate friendliness of burned-out knowledge workers. They aren’t pieces of media so much as second jobs or second lives — a way to pursue our hobbies when we have no time to spare, to have smart people talk at us when we have no time to think, to have new books summarized when we have no time to read. Our relationship with podcasts exists in uninterrupted parallel to the rest of our existence, a wealth of knowledge ready to be tapped at any moment. Podcasts intensify our saturation while pretending to relieve it. It’s like a voluntary authoritarian state, except instead of state-funded sitcoms, we have Marc Maron. But what would we do without it? Die, probably. Be murdered. Become a true-crime podcast. Don’t forget us when we’re gone; please rate us on iTunes.

more here.

Jean Vanier: Founder of L’Arche dies aged 90

Martin Bashir at the BBC:

He studied theology and philosophy, completing his doctoral studies on happiness in the ethics of Aristotle. He became a teaching professor at St Michael’s College in Toronto.

He studied theology and philosophy, completing his doctoral studies on happiness in the ethics of Aristotle. He became a teaching professor at St Michael’s College in Toronto.

During the Christmas holidays of 1964, he visited a friend who was working as a chaplain for men with learning difficulties just outside Paris. Disturbed by conditions in which 80 men did nothing but walk around in circles, he bought a small house nearby and invited two men from the institution to join him.

L’Arche – the Ark – was born.

Vanier said that living with the disabled helped him to appreciate two truths: first, that people with learning difficulties have a great deal to contribute; second, by living in a community with people – with and without learning disabilities – we open ourselves up to be challenged and to grow.

more here.

The Politics of Humor

Terry Eagleton at Commonweal:

The governing elites of ancient and medieval Europe were not greatly hospitable to humor. From the earliest times, laughter seems to have been a class affair, with a firm distinction enforced between civilized amusement and vulgar cackling. Aristotle insists on the difference between the humor of well-bred and low-bred types in the Nicomachean Ethics. He assigns an exalted place to wit, ranking it alongside friendship and truthfulness as one of the three social virtues, but the style of wit in question demands refinement and education, as does the deployment of irony. Plato’s Republic sets its face sternly against holding citizens up to ridicule and is content to abandon comedy largely to slaves and aliens. Mockery can be socially disruptive, and abuse dangerously divisive. The cultivation of laughter among the Guardian class is sternly discouraged, along with images of laughing gods or heroes. St. Paul forbids jesting, or what he terms eutrapelia, in his Epistle to the Ephesians. It is likely, however, that Paul has scurrilous buffoonery in mind, rather than the vein of urbane wit of which Aristotle would have approved.

The governing elites of ancient and medieval Europe were not greatly hospitable to humor. From the earliest times, laughter seems to have been a class affair, with a firm distinction enforced between civilized amusement and vulgar cackling. Aristotle insists on the difference between the humor of well-bred and low-bred types in the Nicomachean Ethics. He assigns an exalted place to wit, ranking it alongside friendship and truthfulness as one of the three social virtues, but the style of wit in question demands refinement and education, as does the deployment of irony. Plato’s Republic sets its face sternly against holding citizens up to ridicule and is content to abandon comedy largely to slaves and aliens. Mockery can be socially disruptive, and abuse dangerously divisive. The cultivation of laughter among the Guardian class is sternly discouraged, along with images of laughing gods or heroes. St. Paul forbids jesting, or what he terms eutrapelia, in his Epistle to the Ephesians. It is likely, however, that Paul has scurrilous buffoonery in mind, rather than the vein of urbane wit of which Aristotle would have approved.

more here.

Wednesday Poem

Eviction

the whites cry in their houses

because they’ve had to evict the guests.

the last names and the properties cry

because they’ve burned

the worms’ deeds.

how sad the disillusionment!

how sad the death of love and hope!

the writings cry for the forgotten oralities.

the coldness of the rebel incites the handkerchiefs to come out

and cry through the streets like mary magdalene.

the world ends and those who end it never end up crying,

but when they reach the water ay ay what laments

what bodies of water that flood the planet.

the buried mountains of my island

sit like lost treasures at the bottom of a sea

that is more spume than water.

this poem is personal.

as personal as colonialism and private property.

this poem doesn’t cry because it is worse than an evicted tenant.

this poem doesn’t have friends or time to move,

but still moves.

(a curse on the house that still smells like my mouth)

either way, what is a poem without the rent,

a couple without equality or love

between landlord and tenant?

wouldn’t pain be inevitable

if you don’t pay the first of the month?

they say that what i am saying is unfair

that really we should be careful.

we all have bills.

the world makes us cruel.

but i am not of the world,

not even of this planet.

i happened to land here

and my ship ran out of gas.

i stayed because i had no choice.

i fell in love because soy una pendeja

and because the people here are beautiful

when they don’t kick us out.

since my arrival,

i’ve had various lovely houses.

one had green walls

and a white and open kitchen.

another smelled like sage and rusty books.

my favorite had two cats and two people in love.

all evicted me to drain the roofs.

the houses with their whites cry

over the end of the neighborhoods

and with their white nostalgia

for the end of childhood and backyards.

by Raquel Salas Rivera

from Split This Rock

Read more »

Tuesday, May 7, 2019

The Case for Nabokov

Cathy Young in Quillette:

Vladimir Nabokov, whose 120th anniversary we mark this Spring, remains one of the 20th Century’s most acclaimed and enduring writers. He keeps turning up on various Greatest–Books lists, often more than once—for the novels Lolita and Pale Fire, as well as his autobiography, Speak, Memory. And yet in this day and age, Nabokov is clearly a “problematic” fave. Not only is he a dead white male of privileged pedigree, but the novel that made him a literary star is, in the scolding words of feminist essayist Rebecca Solnit, “a book about a white man serially raping a child.” What’s more, Nabokov, a Russian-born refugee from both Communism and Nazism who died in 1977, made no secret of his contempt for both progressive political causes and literature as a means to advance them. He was politically incorrect avant la lettre.

Vladimir Nabokov, whose 120th anniversary we mark this Spring, remains one of the 20th Century’s most acclaimed and enduring writers. He keeps turning up on various Greatest–Books lists, often more than once—for the novels Lolita and Pale Fire, as well as his autobiography, Speak, Memory. And yet in this day and age, Nabokov is clearly a “problematic” fave. Not only is he a dead white male of privileged pedigree, but the novel that made him a literary star is, in the scolding words of feminist essayist Rebecca Solnit, “a book about a white man serially raping a child.” What’s more, Nabokov, a Russian-born refugee from both Communism and Nazism who died in 1977, made no secret of his contempt for both progressive political causes and literature as a means to advance them. He was politically incorrect avant la lettre.

And so it is not surprising that anti-Nabokov rumblings have been bubbling up in recent years. They include Solnit’s widely praised 2015 essay “Men Explain Lolita to Me,” in which she wrote about being lectured by males online after daring to question the misogynistic literary canon. (That piece, as I pointed out in a review of Solnit’s essay collection, is based on a fraud: Solnit’s chief mansplainer turned out to be a woman with a gender-ambiguous name who was not lecturing Solnit, but was talking to someone else in a Facebook group. When caught out by commenters, Solnit made surreptitious face-saving edits such as changing “this man” to “this reader.”)

While Solnit offered the disclaimer that “I had never said that we shouldn’t read Lolita,” she clearly seemed to include it among books that treat women as “dirt.” Some got the message. Author, editor and literary publicist Kait Heacock wrotethat, partly due to Solnit’s essay, she has decided to “break up” with her once-beloved Lolita because she will no longer support literature “built on the backs of young girls.”

More here.

Sean Carroll’s Mindscape Podcast: Leonard Susskind on Quantum Information, Quantum Gravity, and Holography

Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

For decades now physicists have been struggling to reconcile two great ideas from a century ago: general relativity and quantum mechanics. We don’t yet know the final answer, but the journey has taken us to some amazing places. A leader in this quest has been Leonard Susskind, who has helped illuminate some of the most mind-blowing ideas in quantum gravity: the holographic principle, the string theory landscape, black-hole complementarity, and others. He has also become celebrated as a writer, speaker, and expositor of mind-blowing ideas. We talk about black holes, quantum mechanics, and the most exciting new directions in quantum gravity.

For decades now physicists have been struggling to reconcile two great ideas from a century ago: general relativity and quantum mechanics. We don’t yet know the final answer, but the journey has taken us to some amazing places. A leader in this quest has been Leonard Susskind, who has helped illuminate some of the most mind-blowing ideas in quantum gravity: the holographic principle, the string theory landscape, black-hole complementarity, and others. He has also become celebrated as a writer, speaker, and expositor of mind-blowing ideas. We talk about black holes, quantum mechanics, and the most exciting new directions in quantum gravity.

More here.

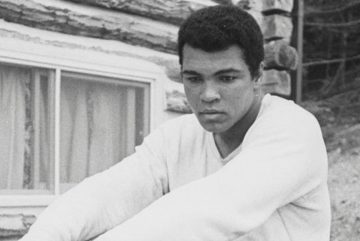

Telling Muhammad Ali’s story in full: “What really struck me the most was how much humility he had”

Rachel Leah in Salon:

The opening frame of “What’s My Name” shows Ali explaining that should his story ever be told, he wants it done in full. So, there are no talking heads or narration, because who better to tell such a remarkable, revolutionary story than Muhammad Ali himself? His interviews and words guide us through his life, from early childhood until his final days, as he endures the bodily constraints of Parkinson’s disease. Ali’s famous, rhythmic one-liners, like “float like a butterfly, sting like a bee,” are accompanied by his critical analysis about race, white supremacy and his politics, which are global.

The opening frame of “What’s My Name” shows Ali explaining that should his story ever be told, he wants it done in full. So, there are no talking heads or narration, because who better to tell such a remarkable, revolutionary story than Muhammad Ali himself? His interviews and words guide us through his life, from early childhood until his final days, as he endures the bodily constraints of Parkinson’s disease. Ali’s famous, rhythmic one-liners, like “float like a butterfly, sting like a bee,” are accompanied by his critical analysis about race, white supremacy and his politics, which are global.

“What’s My Name” doesn’t just show the extreme bravery of Ali’s activism, as he spoke expertly and passionately about the plight of black people in America and the perils of U.S. empire, but it also focuses on the immense sacrifices he made — how Ali put his life, safety and career on the line for his convictions and was punished immensely for it — marginalized and dehumanized by his own country. Ali is universally celebrated today, but like many black radical activists, he was undercut during the zenith of his life.

More here.