Honor Moore at The Paris Review:

There is a way in which all of Bette Howland’s characters seem like visitors from a parallel universe, where they are free rather than confined. This is the eponymous visitor in the opening story of this collection: “I was catching on at last. The bad roads, the crash, the minor injury. This petty bureaucrat. This place. Sir? I’m dead? Is that it? I’m dead? … That’s what they all want to know! he said. But that’s the whole show! I can’t give that away, can I?” An uncle’s young wife is “a big handsome Southern girl, rawboned, rock jawed, her pale head dropped over her knitting. Peculiarly pale; translucent, like rock candy, and almost as brittle.” It is as if they step into a room accompanied by their own lighting. “ ‘When are you going to get married?’ Uncle Rudy asked, towering over me.” Imagination is what she calls what she does with them, imaginative selection from the panoply of life. “He’s a scofflaw. He’ll go out of his way to park illegally. He’ll drive around the block looking for a No Parking sign or a nice little fire hydrant.” Reading the prose brings a Bette I’d forgotten—a glass of Scotch, how she threw back her head and uproariously laughed. Ah, yes; here’s the one with verve, the woman in the fedora photo.

There is a way in which all of Bette Howland’s characters seem like visitors from a parallel universe, where they are free rather than confined. This is the eponymous visitor in the opening story of this collection: “I was catching on at last. The bad roads, the crash, the minor injury. This petty bureaucrat. This place. Sir? I’m dead? Is that it? I’m dead? … That’s what they all want to know! he said. But that’s the whole show! I can’t give that away, can I?” An uncle’s young wife is “a big handsome Southern girl, rawboned, rock jawed, her pale head dropped over her knitting. Peculiarly pale; translucent, like rock candy, and almost as brittle.” It is as if they step into a room accompanied by their own lighting. “ ‘When are you going to get married?’ Uncle Rudy asked, towering over me.” Imagination is what she calls what she does with them, imaginative selection from the panoply of life. “He’s a scofflaw. He’ll go out of his way to park illegally. He’ll drive around the block looking for a No Parking sign or a nice little fire hydrant.” Reading the prose brings a Bette I’d forgotten—a glass of Scotch, how she threw back her head and uproariously laughed. Ah, yes; here’s the one with verve, the woman in the fedora photo.

more here.

WASHINGTON — Humans are transforming Earth’s natural landscapes so dramatically that as many as one million plant and animal species are now at risk of extinction, posing a dire threat to ecosystems that people all over the world depend on for their survival, a sweeping new United Nations assessment has concluded. The 1,500-page report, compiled by hundreds of international experts and based on thousands of scientific studies, is the most exhaustive look yet at the decline in biodiversity across the globe and the dangers that creates for human civilization. A

WASHINGTON — Humans are transforming Earth’s natural landscapes so dramatically that as many as one million plant and animal species are now at risk of extinction, posing a dire threat to ecosystems that people all over the world depend on for their survival, a sweeping new United Nations assessment has concluded. The 1,500-page report, compiled by hundreds of international experts and based on thousands of scientific studies, is the most exhaustive look yet at the decline in biodiversity across the globe and the dangers that creates for human civilization. A  When I was laid off in 2015, I told people about it the way any good millennial would: By tweeting it. My hope was that someone on the fringes of my social sphere would point me to potential opportunities. To my surprise, the gambit worked. Shortly after my public plea for employment, a friend of a friend sent me a Facebook message alerting me to an opening in her department. Three rounds of interviews later, this acquaintance was my boss. (She’s now one of my closest friends).

When I was laid off in 2015, I told people about it the way any good millennial would: By tweeting it. My hope was that someone on the fringes of my social sphere would point me to potential opportunities. To my surprise, the gambit worked. Shortly after my public plea for employment, a friend of a friend sent me a Facebook message alerting me to an opening in her department. Three rounds of interviews later, this acquaintance was my boss. (She’s now one of my closest friends). In the opening of The Other Americans, Laila Lalami’s fourth novel, a man is killed in a hit-and-run collision. The victim is Driss Guerraoui, an immigrant and small business owner who, after fleeing political unrest in Casablanca, eventually settles in a small town in California’s Mojave Desert to open a business and raise his family. His immigrant story is one his younger daughter Nora, a jazz composer, considers with mixed feelings. “I think he liked that story because it had the easily discernible arc of the American Dream: Immigrant Crosses Ocean, Starts a Business, Becomes a Success.” And it’s this clichéd American-immigrant narrative that Lalami sets out to deconstruct in her book.

In the opening of The Other Americans, Laila Lalami’s fourth novel, a man is killed in a hit-and-run collision. The victim is Driss Guerraoui, an immigrant and small business owner who, after fleeing political unrest in Casablanca, eventually settles in a small town in California’s Mojave Desert to open a business and raise his family. His immigrant story is one his younger daughter Nora, a jazz composer, considers with mixed feelings. “I think he liked that story because it had the easily discernible arc of the American Dream: Immigrant Crosses Ocean, Starts a Business, Becomes a Success.” And it’s this clichéd American-immigrant narrative that Lalami sets out to deconstruct in her book. This week, amid devastating

This week, amid devastating  If someone says, “I guess it’s in my DNA,” you never hear people say, “DN—what?” We all know what DNA is, or at least think we do.

If someone says, “I guess it’s in my DNA,” you never hear people say, “DN—what?” We all know what DNA is, or at least think we do. For a few months in 2008 and 2009 many people feared that the world economy was on the verge of collapse…

For a few months in 2008 and 2009 many people feared that the world economy was on the verge of collapse… Cyril Connolly once wrote: “The more books we read, the clearer it becomes that the true function of a writer is to produce a masterpiece and that no other task is of any consequence.” This is tosh, of course, for if every book were a masterpiece, no book would be a masterpiece and we could not know a masterpiece when we read it. They also serve who only sit and write trash. To know the good, we have to know the bad. The precise quantity and degree of the bad that we have to know in order to appreciate the good is debatable, and certainly there is no great difficulty in finding the bad, whether it be bad food, bad films, bad theatre productions, bad behaviour or bad books. Indeed, the only thing that can be said in favour of the current overwhelming prevalence of the bad is that it adds to the pleasure of finding the good — the piquancy both of discovery and relief.

Cyril Connolly once wrote: “The more books we read, the clearer it becomes that the true function of a writer is to produce a masterpiece and that no other task is of any consequence.” This is tosh, of course, for if every book were a masterpiece, no book would be a masterpiece and we could not know a masterpiece when we read it. They also serve who only sit and write trash. To know the good, we have to know the bad. The precise quantity and degree of the bad that we have to know in order to appreciate the good is debatable, and certainly there is no great difficulty in finding the bad, whether it be bad food, bad films, bad theatre productions, bad behaviour or bad books. Indeed, the only thing that can be said in favour of the current overwhelming prevalence of the bad is that it adds to the pleasure of finding the good — the piquancy both of discovery and relief. OVER THE PAST FEW YEARS—

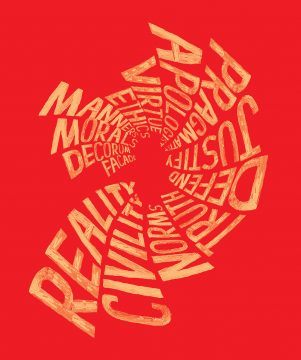

OVER THE PAST FEW YEARS— If you don’t stand for something, you’ll fall for anything,” as an old piece of political folk wisdom holds. The

If you don’t stand for something, you’ll fall for anything,” as an old piece of political folk wisdom holds. The  When

When  Soraya Roberts in Longreads:

Soraya Roberts in Longreads: First published in 1952, Lillian Ross’s Picture, an eyewitness report of director John Huston’s adaptation of The Red Badge of Courage, remains the paradigm of a slim genre, the nonfiction account of a movie’s making (and unmaking): from shooting to editing to studio meddling to publicity planning to preview screening to more studio meddling to, finally, theatrical release. The book is populated by raffish heroes (Huston) and tyrannical philistines (Louis B. Mayer), by the beleaguered (producer Gottfried Reinhardt) and the overweening (MGM head of production Dore Schary), and by various hypocrites, toadies, greenhorns, and wives. Envisioned by Ross as “a fact piece in novel form, or maybe a novel in fact form,” Picture endures as a key work of proto–New Journalism. Though Ross, a writer for more than sixty years at the New Yorker—where Picture, under the title “Production Number 1512,” was first published, in five installments—was renowned for her fly-on-the-wall reporting, she is not always invisible in the book; “I” pops up intermittently.

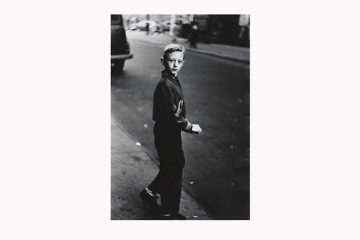

First published in 1952, Lillian Ross’s Picture, an eyewitness report of director John Huston’s adaptation of The Red Badge of Courage, remains the paradigm of a slim genre, the nonfiction account of a movie’s making (and unmaking): from shooting to editing to studio meddling to publicity planning to preview screening to more studio meddling to, finally, theatrical release. The book is populated by raffish heroes (Huston) and tyrannical philistines (Louis B. Mayer), by the beleaguered (producer Gottfried Reinhardt) and the overweening (MGM head of production Dore Schary), and by various hypocrites, toadies, greenhorns, and wives. Envisioned by Ross as “a fact piece in novel form, or maybe a novel in fact form,” Picture endures as a key work of proto–New Journalism. Though Ross, a writer for more than sixty years at the New Yorker—where Picture, under the title “Production Number 1512,” was first published, in five installments—was renowned for her fly-on-the-wall reporting, she is not always invisible in the book; “I” pops up intermittently. In the era of Instagram and YouTube, when photography has mostly become a means of projecting oneself into the world to gauge its reaction, it takes an imaginative leap to recognize how revolutionary Diane Arbus’s murky photographs of some of the more disturbing corners of

In the era of Instagram and YouTube, when photography has mostly become a means of projecting oneself into the world to gauge its reaction, it takes an imaginative leap to recognize how revolutionary Diane Arbus’s murky photographs of some of the more disturbing corners of  I

I