by Bill Murray

Two minutes after the explosion the fire station alarm rang. The firefighters who scrambled from sleep to the scene, along with the regular overnight shift at reactor four, were among the first fatally irradiated. Unquestioned heroes, they battled the blazes until dawn with no special training for a nuclear accident, in shirtsleeves, using only conventional firefighting methods. They walked amid flaming, radioactive graphite.

Two minutes after the explosion the fire station alarm rang. The firefighters who scrambled from sleep to the scene, along with the regular overnight shift at reactor four, were among the first fatally irradiated. Unquestioned heroes, they battled the blazes until dawn with no special training for a nuclear accident, in shirtsleeves, using only conventional firefighting methods. They walked amid flaming, radioactive graphite.

The power station fire brigade arrived first. Lieutenant Volodymyr Pravik, their commander, saw right away he needed help and called in fire brigades from the little towns of Pripyat and Chernobyl. When Pravik died thirteen days later he was a month shy of age twenty-four.

“We arrived there at 10 or 15 minutes to two in the morning,” said fire engine driver Grigorii Khmal.

“We saw graphite scattered about. Misha asked: Is that graphite? I kicked it away. But one of the fighters on the other truck picked it up. It’s hot, he said. The pieces of graphite were of different sizes, some big, some small enough to pick them up….

“We didn’t know much about radiation. Even those who worked there had no idea. There was no water left in the trucks. Misha filled a cistern and we aimed the water at the top. Then those boys who died went up to the roof – Vashchik, Kolya and others, and Volodya Pravik…. They went up the ladder … and I never saw them again.”

Another fireman told the BBC, “It was dark because it was night. On the other hand, you could see and even recognize a person from 10 to 15 meters. It was if (sic) the sun was rising, but with a strange light.”

They climbed to the roof of what was left of reactor four, preventing fire from spreading to the other three reactors and so preventing what could have been a truly ghastly night. By 5:00 a.m. all the fires were out save for the one in the reactor. That fire burned for ten days. It took 5000 tons of sand, boron, dolomite and clay dropped from helicopters to put it out. Read more »

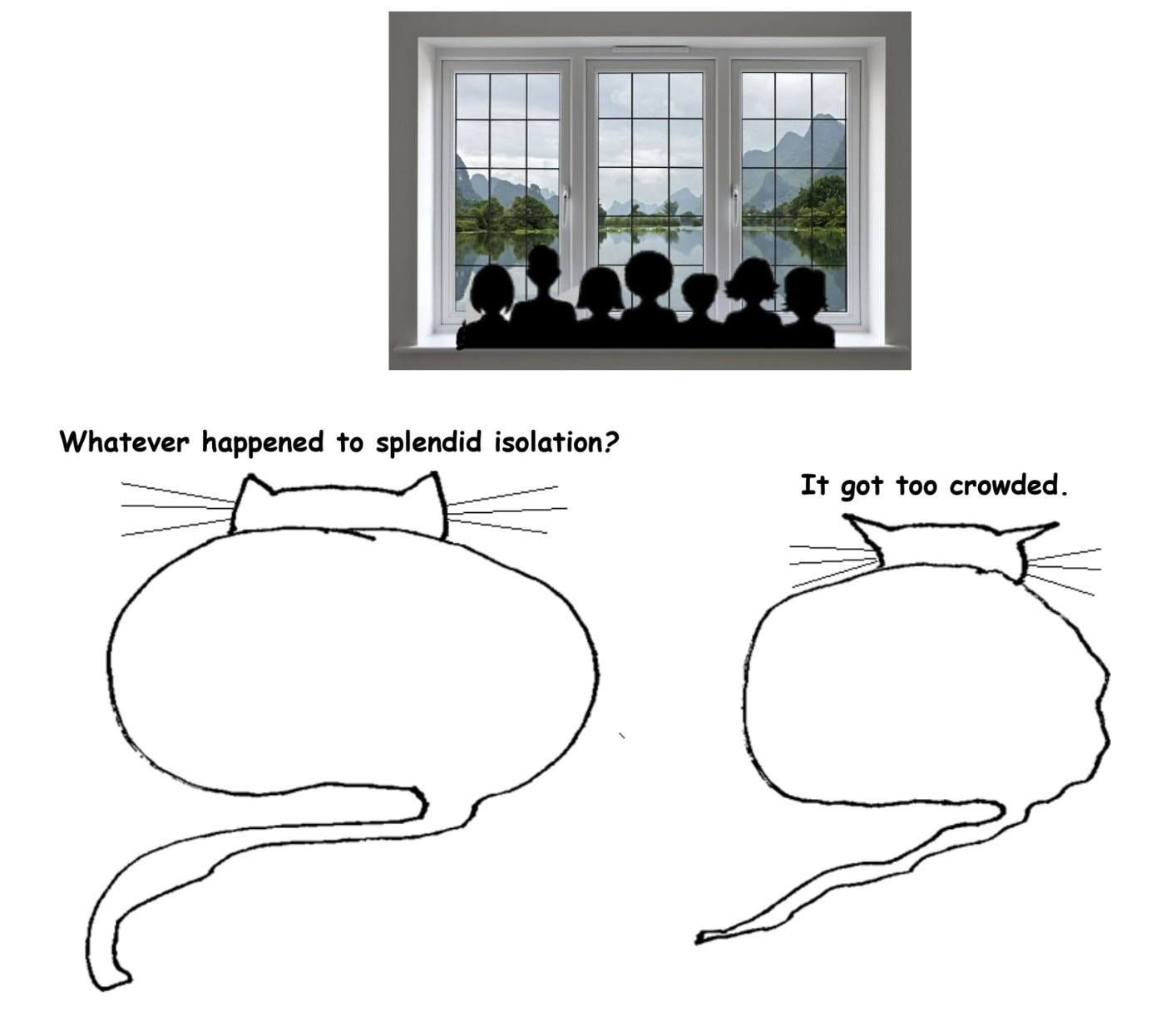

by Holly A. Case (Interviewer) and Tom J. W. Case (Hermit)

by Holly A. Case (Interviewer) and Tom J. W. Case (Hermit)

I’ve been telecommuting on and off for over 17 years. I first started working from home because I’d moved 150 miles away from the company I’d been contracting for over the previous 4 years. Back then, I worked in a small team that was part of a larger team in a huge corporation. My immediate boss was very supportive of my new working arrangement, but he had a peer, who even though she had no responsibility for my work, felt the need to have her say to their mutual boss. Her thoughts went along lines of, “how do we know she’s really working when she never comes into the office?”, to which my boss said, “well someone is getting all the work done, so if it isn’t Sarah, who is it?”. This conversation seems almost quaint nowadays, when even before the current pandemic, a decent amount of the white-collar professional workforce worked at least occasionally from home. And now of course, we’ve all been thrust into a great social experiment to see just how productive, perhaps more rather than less even, the entire workforce will be working remotely. Everyone else is now catching up to what I’ve known for a long time: it’s pretty nice to not have to deal with the daily commute and that time can really be used more productively than fighting for space on mass transit; you have to be at least somewhat disciplined to make sure you only go so many days working in the same pjs you’ve been in all week; working from home can give you a lot of time to multitask life stuff like unloading the dishwasher while you’re listening to a conference call, but it can also be harder to draw boundaries between home and work life, and this takes some practice.

I’ve been telecommuting on and off for over 17 years. I first started working from home because I’d moved 150 miles away from the company I’d been contracting for over the previous 4 years. Back then, I worked in a small team that was part of a larger team in a huge corporation. My immediate boss was very supportive of my new working arrangement, but he had a peer, who even though she had no responsibility for my work, felt the need to have her say to their mutual boss. Her thoughts went along lines of, “how do we know she’s really working when she never comes into the office?”, to which my boss said, “well someone is getting all the work done, so if it isn’t Sarah, who is it?”. This conversation seems almost quaint nowadays, when even before the current pandemic, a decent amount of the white-collar professional workforce worked at least occasionally from home. And now of course, we’ve all been thrust into a great social experiment to see just how productive, perhaps more rather than less even, the entire workforce will be working remotely. Everyone else is now catching up to what I’ve known for a long time: it’s pretty nice to not have to deal with the daily commute and that time can really be used more productively than fighting for space on mass transit; you have to be at least somewhat disciplined to make sure you only go so many days working in the same pjs you’ve been in all week; working from home can give you a lot of time to multitask life stuff like unloading the dishwasher while you’re listening to a conference call, but it can also be harder to draw boundaries between home and work life, and this takes some practice.

I had planned to do another philosophy post this month, but I can hardly concentrate on such things about now and I bet you can’t either. Instead I’ve been hanging out on Bandcamp and

I had planned to do another philosophy post this month, but I can hardly concentrate on such things about now and I bet you can’t either. Instead I’ve been hanging out on Bandcamp and

Manhattan always has been and always will be New York City’s geographic and economic center. But if you’re actually from New York, then you’re very likely not from Manhattan. Like me, you’re from one of the outer boroughs: The Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens, or Staten Island. And as far as we’re concerned, we’re the real New Yorkers. The natives with roots and connections, and the immigrants who are life-and-death dedicated to making them, not the tourists who come for a weekend or a dozen years before trundling back to America.

Manhattan always has been and always will be New York City’s geographic and economic center. But if you’re actually from New York, then you’re very likely not from Manhattan. Like me, you’re from one of the outer boroughs: The Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens, or Staten Island. And as far as we’re concerned, we’re the real New Yorkers. The natives with roots and connections, and the immigrants who are life-and-death dedicated to making them, not the tourists who come for a weekend or a dozen years before trundling back to America.

Kazuo Shiraga. Untitled 1964.

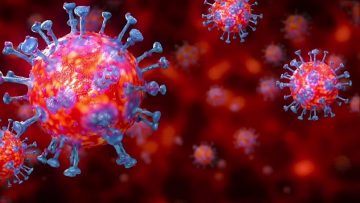

Kazuo Shiraga. Untitled 1964. There has been much discussion lately of whether the COVID-19 pandemic will spell the end of globalization. It’s hard to get economists to agree on the meaning of the numbers, or foreign policy analysts to commit to a vision of the future in a world that changes from one moment to the next. Globalization means different things to different people and entities. Its many facets, and many narratives about those facets, complicate discussion about either a contraction or a resurgence of globalization. For corporations, it means access to inexpensive labor markets; for money managers, it means access to capital markets. For the typical business traveler, it may mean something as basic as greater choice of airlines and flight times for an international trip. For an optimistic humanist, it might symbolize enhanced international cooperation and a suppression of nationalism and xenophobia. For an environmentalist, it is marred by the dangerous policies that accelerate climate change. For a technocrat, it seems the obvious economic approach to accompany the paradigm of social-media-fueled connectedness, data collection, surveillance, and targeted marketing.

There has been much discussion lately of whether the COVID-19 pandemic will spell the end of globalization. It’s hard to get economists to agree on the meaning of the numbers, or foreign policy analysts to commit to a vision of the future in a world that changes from one moment to the next. Globalization means different things to different people and entities. Its many facets, and many narratives about those facets, complicate discussion about either a contraction or a resurgence of globalization. For corporations, it means access to inexpensive labor markets; for money managers, it means access to capital markets. For the typical business traveler, it may mean something as basic as greater choice of airlines and flight times for an international trip. For an optimistic humanist, it might symbolize enhanced international cooperation and a suppression of nationalism and xenophobia. For an environmentalist, it is marred by the dangerous policies that accelerate climate change. For a technocrat, it seems the obvious economic approach to accompany the paradigm of social-media-fueled connectedness, data collection, surveillance, and targeted marketing.

1. As the coronavirus continues to disrupt human life in many corners of the globe, a phrase from George Frideric Handel’s Messiah has wormed its way through the background noise of my attention span. It occurs in a Part III

1. As the coronavirus continues to disrupt human life in many corners of the globe, a phrase from George Frideric Handel’s Messiah has wormed its way through the background noise of my attention span. It occurs in a Part III  We get half a sunny day every other day since Corona has coaxed us to quit public spaces. In the past fortnight or so, sunlight has been in short supply just as masks, disinfectant spray and toilet paper. When the sun is out, it’s no ordinary gift; it brings a rush of joy that wipes out not only the free-floating, dystopic COVID -19 anxiety, but also the other recent traumas we’ve faced as a family. Indoors, socially-distant by three feet, hunched over our phones for news of loved ones, we forget it is spring, but mornings the sunlight hits the windows feel as if God has turned on the power-wash setting: one is shocked into vigor, tricked into optimism. On such a day, I step down the patio threshold as if pulled by a magnet; just out of the shower and still combing my wet hair, I’m suddenly aware of another gift— soap.

We get half a sunny day every other day since Corona has coaxed us to quit public spaces. In the past fortnight or so, sunlight has been in short supply just as masks, disinfectant spray and toilet paper. When the sun is out, it’s no ordinary gift; it brings a rush of joy that wipes out not only the free-floating, dystopic COVID -19 anxiety, but also the other recent traumas we’ve faced as a family. Indoors, socially-distant by three feet, hunched over our phones for news of loved ones, we forget it is spring, but mornings the sunlight hits the windows feel as if God has turned on the power-wash setting: one is shocked into vigor, tricked into optimism. On such a day, I step down the patio threshold as if pulled by a magnet; just out of the shower and still combing my wet hair, I’m suddenly aware of another gift— soap.