by Paul Braterman

This book will be of interest to anyone who is interested in the way in which evolution actually proceeds, and the insights that we are now gaining into the genome, which controls the process. The author, Neil Shubin, has made major contributions to our understanding, using in turn the traditional methods of palaeontology and comparative anatomy, and the newer methods of molecular biology that have emerged in the last few decades. He is writing about subject matter that he knows intimately, often describing the contributions of scientists that he knows personally. Like Shubin’s earlier writings, the book is a pleasure to read, and I was not surprised to learn here that Shubin was a teaching assistant in Stephen Jay Gould’s lectures on the history of life.

Shubin is among other things Professor of Organismal Biology and Anatomy at the University of Chicago. He first came to the attention of a wider public for the discovery of Tiktaalik, completing the bridge between lungfish and terrestrial tetrapods, and that work is described and placed in context in his earlier book, Your Inner Fish. The present volume is an overview, from his unique perspective, of our understanding of evolutionary change, from Darwin, through detailed palaeontological studies, and into the current era of molecular biology, a transition that, as he reminds us, parallels his own intellectual evolution.

In addition to the underlying science narrative, we have a wealth of biographical detail regarding those involved in the discoveries being discussed, and the milieu in which they worked. These details are not mere embroidery, but an integral part of his exposition. For example, I was aware that Linus Pauling, with Emil Zuckerkandl, was a pioneer in the use of sequence differences as a molecular clock, but did not know how this related to Pauling’s interest in radiation damage to proteins, a topic that brought together his scientific and political concerns. Read more »

Over the past week, Pakistan has been consumed by the Aurat (Women’s) March, which was held today, March 8, International Women’s Day, in all the major cities of the country. The march’s aim is to highlight the continued discrimination, inequality, and harassment suffered by women. There are some people against it who argue that the march should not be allowed, but the Islamabad High Court has rejected the petition that asked for its cancellation. So the march happened.

Over the past week, Pakistan has been consumed by the Aurat (Women’s) March, which was held today, March 8, International Women’s Day, in all the major cities of the country. The march’s aim is to highlight the continued discrimination, inequality, and harassment suffered by women. There are some people against it who argue that the march should not be allowed, but the Islamabad High Court has rejected the petition that asked for its cancellation. So the march happened. During a recent visit to Paris, I squeezed through the crowded bookshelves of the famous Shakespeare and Company bookstore, a stone’s throw from Notre Dame, whose charred heights sat masked in scaffolding just across the Seine. It has become something of a Parisian tourist hotspot, mostly because of its association with our favorite Modernist expat writers, immortalized and gilded in a cosmopolitan, angsty, and glamorous mystique through the canonization of their works and, some might argue, the award-winning Woody Allen film Midnight in Paris.

During a recent visit to Paris, I squeezed through the crowded bookshelves of the famous Shakespeare and Company bookstore, a stone’s throw from Notre Dame, whose charred heights sat masked in scaffolding just across the Seine. It has become something of a Parisian tourist hotspot, mostly because of its association with our favorite Modernist expat writers, immortalized and gilded in a cosmopolitan, angsty, and glamorous mystique through the canonization of their works and, some might argue, the award-winning Woody Allen film Midnight in Paris.

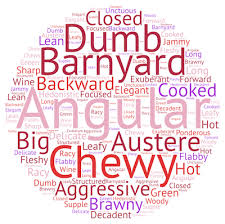

Research by linguists

Research by linguists

There was this one moment. A sunny June day in Nebraska. No one was around. I dribbled the basketball over the warm blacktop, moving towards a modest hoop erected at the end of a Lutheran church parking lot. I picked up my dribble, took two steps, sprung lightly from my left foot, up and forward, my right arm extending as my hand gracefully served the ball to the white backboard. Its upward angle peaked, bounced softly, and descended back through the netless hoop.

There was this one moment. A sunny June day in Nebraska. No one was around. I dribbled the basketball over the warm blacktop, moving towards a modest hoop erected at the end of a Lutheran church parking lot. I picked up my dribble, took two steps, sprung lightly from my left foot, up and forward, my right arm extending as my hand gracefully served the ball to the white backboard. Its upward angle peaked, bounced softly, and descended back through the netless hoop.

What is commonsense to most people who received a K-12 public education in the United States is that every formal system of state schooling throughout the modern world is designed to educate its students to develop, what Charles Lemert calls “sociologically competencies” within whatever ideological system is dominating at the time of their schooling. People correctly assume that children going to school during the Weimar Republic, for example, were educated to function competently within that ideological system. Children who were in school during the reign of Chairman Mao in the People’s Republic of China were educated to function competently within that system. Children in China today are educated to be sociologically competent in China’s current government and economic system. Children in France, Spain, Portugal, Israel, Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, and Iran likewise are educated to function competently in those systems. In the Soviet Union, children were educated to function within its version of communism. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, children were required to learn different civic knowledge and skills in order to be competent within the newly emerging political ideologies of reformed nation states.

What is commonsense to most people who received a K-12 public education in the United States is that every formal system of state schooling throughout the modern world is designed to educate its students to develop, what Charles Lemert calls “sociologically competencies” within whatever ideological system is dominating at the time of their schooling. People correctly assume that children going to school during the Weimar Republic, for example, were educated to function competently within that ideological system. Children who were in school during the reign of Chairman Mao in the People’s Republic of China were educated to function competently within that system. Children in China today are educated to be sociologically competent in China’s current government and economic system. Children in France, Spain, Portugal, Israel, Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, and Iran likewise are educated to function competently in those systems. In the Soviet Union, children were educated to function within its version of communism. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, children were required to learn different civic knowledge and skills in order to be competent within the newly emerging political ideologies of reformed nation states.

Notwithstanding the spread of English as a global lingua franca, translation continues to be a vital component of international relations, whether political, commercial, or cultural. In certain cases, translation is also necessary nationally, for instance in countries comprising more than one significant linguistic group. This is so in Switzerland, which voted by an overwhelming majority in 1938 to add a fourth national tongue to thwart the irredentist aspirations of its Italian neighbor, and which in certain contexts is obliged to use a Latin version of its own name (Confoederatio Helvetica) to avoid favoring one language group over another.

Notwithstanding the spread of English as a global lingua franca, translation continues to be a vital component of international relations, whether political, commercial, or cultural. In certain cases, translation is also necessary nationally, for instance in countries comprising more than one significant linguistic group. This is so in Switzerland, which voted by an overwhelming majority in 1938 to add a fourth national tongue to thwart the irredentist aspirations of its Italian neighbor, and which in certain contexts is obliged to use a Latin version of its own name (Confoederatio Helvetica) to avoid favoring one language group over another. If you listen to that track as featured in the mix, my judgment may seem a little harsh. The track is on the static side, but that’s hardly a fault in the context: the textures are lovely, and there’s plenty of movement; and at under four minutes it can’t really be said to overstay its welcome. A minor work, perhaps, but as a brief linking interlude it works perfectly well. So what’s the problem?

If you listen to that track as featured in the mix, my judgment may seem a little harsh. The track is on the static side, but that’s hardly a fault in the context: the textures are lovely, and there’s plenty of movement; and at under four minutes it can’t really be said to overstay its welcome. A minor work, perhaps, but as a brief linking interlude it works perfectly well. So what’s the problem?

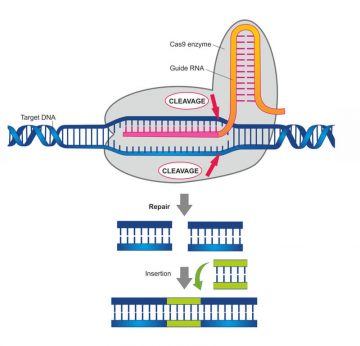

front of some her UC Berkeley colleagues, Doudna shared, “a story … about some research … that led in an unexpected direction … ” producing “ … some science that has profound implications going forward…but also makes us really think about what it means to be human and what it means to have the power to manipulate the very code of life …”

front of some her UC Berkeley colleagues, Doudna shared, “a story … about some research … that led in an unexpected direction … ” producing “ … some science that has profound implications going forward…but also makes us really think about what it means to be human and what it means to have the power to manipulate the very code of life …” He is an enigma. He sits up there in his marble chair, set in a Greek temple, literally larger than life, and he defies us to understand him.

He is an enigma. He sits up there in his marble chair, set in a Greek temple, literally larger than life, and he defies us to understand him.