Rachel Fraser in Boston Review:

In 1980 Frances Gabe applied for a patent for a self-cleaning house. The design was based on her own home, which she had worked on for more than a decade. Each room had a sprinkler system installed; at the push of a button, Gabe could send sudsy water pouring over her specially treated furniture. Clean water would then wash the soap away, before draining from the gently sloped floors. Blasts of warm air would dry the room in less than an hour, and the used water flowed into the kennel, to give the Great Dane a bath.

The problem with most houses, Gabe thought, was that they were designed by men, who would never be tasked with cleaning them. The self-cleaning house, she hoped, would free women from the “nerve-twangling bore” of housework. Such hopes are widely shared: a 2019 survey found that self-cleaning homes were the most eagerly anticipated of all speculative technologies.

Cleaning, like cooking, childbearing, and breastfeeding, is a paradigm case of reproductive labor. Reproductive labor is a special form of work. It doesn’t itself produce commodities (coffee pots, silicon chips); rather, it’s the form of work that creates and maintains labor power itself, and hence makes the production of commodities possible in the first place. Reproductive labor is low-prestige and (typically) either poorly paid or entirely unwaged. It’s also obstinately feminized: both within the social imaginary and in actual fact, most reproductive labor is done by women. It is perhaps unsurprising, then, that political discussions of work often treat reproductive labor as an afterthought.

One place this elision shows up is in the “post-work” tradition.

More here.

Is it appropriate to call the three members of the sketch comedy group Please Don’t Destroy “boys”? They are grown men, in a sense, with jobs (Saturday Night Live writers) and, one assumes, growing 401(k)s. They’re in their mid-to-late 20s, six years into a career that started at New York University. Yet in other ways they are very obviously still tweens, gangly and silly, still figuring it all out. They’ve been known to sign emails to reporters “The Boys.” (This was revealed in

Is it appropriate to call the three members of the sketch comedy group Please Don’t Destroy “boys”? They are grown men, in a sense, with jobs (Saturday Night Live writers) and, one assumes, growing 401(k)s. They’re in their mid-to-late 20s, six years into a career that started at New York University. Yet in other ways they are very obviously still tweens, gangly and silly, still figuring it all out. They’ve been known to sign emails to reporters “The Boys.” (This was revealed in  “T

“T This format ensures an extraordinary — and bewildering — range of striking details. We learn that the bloated bodies of those who died in German U-boat attacks wash up along the coastline of Savannah, Ga.; that at the Treblinka death camp “there is almost always a jam when the door of one of the gas chambers is opened,” as the limbs of the corpses are so densely entangled; that when British soldiers in North Africa take five Italian prisoners, one of them happens to be a tenor from the Milan opera, and all five sing as they help with breakfast; that a Chinese civil servant tasked by the Nationalist government with collecting taxes from the starving population of Henan reports that people are eating bark and grass and selling their children for steamed rolls; that U.S. troops at Guadalcanal, desperate for alcohol of any kind, drink after-shave lotion “filtered through bread”; and that when a private with the Red Army northwest of Stalingrad peers out from his trench one night, he discovers a scene of terrible and staggering beauty — a freezing rain, reflecting the full moon’s light, has formed a shimmering veil over the landscape and the corpses of his dead companions.

This format ensures an extraordinary — and bewildering — range of striking details. We learn that the bloated bodies of those who died in German U-boat attacks wash up along the coastline of Savannah, Ga.; that at the Treblinka death camp “there is almost always a jam when the door of one of the gas chambers is opened,” as the limbs of the corpses are so densely entangled; that when British soldiers in North Africa take five Italian prisoners, one of them happens to be a tenor from the Milan opera, and all five sing as they help with breakfast; that a Chinese civil servant tasked by the Nationalist government with collecting taxes from the starving population of Henan reports that people are eating bark and grass and selling their children for steamed rolls; that U.S. troops at Guadalcanal, desperate for alcohol of any kind, drink after-shave lotion “filtered through bread”; and that when a private with the Red Army northwest of Stalingrad peers out from his trench one night, he discovers a scene of terrible and staggering beauty — a freezing rain, reflecting the full moon’s light, has formed a shimmering veil over the landscape and the corpses of his dead companions.

Charlotte Kent (Rail): Photography often gets discussed in terms of its stillness, of capturing or freezing a moment. But, in Where I Find Myself (2018) you wrote about watching Robert Frank and discovering photography’s motion: “that was at the heart of what I had seen: movements, the physicality of it, the timing, the positioning. I played third base, I knew about that kind of movement, it was energy in the service of the moment.” Can you describe how photography was about movement and this physicality? And then maybe also, how baseball comes into that?

Charlotte Kent (Rail): Photography often gets discussed in terms of its stillness, of capturing or freezing a moment. But, in Where I Find Myself (2018) you wrote about watching Robert Frank and discovering photography’s motion: “that was at the heart of what I had seen: movements, the physicality of it, the timing, the positioning. I played third base, I knew about that kind of movement, it was energy in the service of the moment.” Can you describe how photography was about movement and this physicality? And then maybe also, how baseball comes into that?

Many industries are betting that they will benefit from the anticipated quantum-computing revolution. Pharmaceutical companies and electric-vehicle manufacturers have begun to explore the use of quantum computers in chemistry simulations for drug discovery or battery development. Compared with state-of-the-art supercomputers, quantum computers are thought to more efficiently and accurately simulate molecules, which are inherently quantum mechanical in nature.

Many industries are betting that they will benefit from the anticipated quantum-computing revolution. Pharmaceutical companies and electric-vehicle manufacturers have begun to explore the use of quantum computers in chemistry simulations for drug discovery or battery development. Compared with state-of-the-art supercomputers, quantum computers are thought to more efficiently and accurately simulate molecules, which are inherently quantum mechanical in nature. As news of Hamas’s murderous October 7 surprise attack on Israel started to circulate in the global information space, so too did the propaganda. According to one estimate, the Israel-Hamas war sparked the highest volume of global propaganda—emanating not just from Israel, Palestine and other Middle Eastern countries but also from Russia, China, and Iran—that experts had ever seen. Even more so than after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in late February 2022, the outbreak of war between Israel and Hamas was springtime for propaganda.

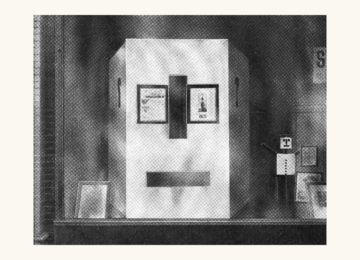

As news of Hamas’s murderous October 7 surprise attack on Israel started to circulate in the global information space, so too did the propaganda. According to one estimate, the Israel-Hamas war sparked the highest volume of global propaganda—emanating not just from Israel, Palestine and other Middle Eastern countries but also from Russia, China, and Iran—that experts had ever seen. Even more so than after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in late February 2022, the outbreak of war between Israel and Hamas was springtime for propaganda. More shadows than men, really; just silhouettes, might as well be smudges on the lens. Hard to notice at first, the two undifferentiated figures in the lower left-hand of the picture, at the corner of the Boulevard du Temple. A bootblack squats down and shines the shoes of a man contrapasso above him; impossible to tell what they’re wearing or what they look like. Obviously no way to ascertain their names or professions. At first they’re hard to recognize as people, these whispers of a figure joined together, eternally preserved by silver-plated copper and mercury vapor; they’re insignificant next to the buildings, elegant Beaux-Arts shops and theaters, wrought iron railings along the streets and chimneys on their mansard roofs. Based on an analysis of the light, Louis Daguerre set up his camera around eight in the morning; leaves are still on trees, so it’s not winter, but otherwise it’s hard to tell what season it is that Paris day in 1838. Whatever their names, it was by accident that they became the first two humans to be photographed.

More shadows than men, really; just silhouettes, might as well be smudges on the lens. Hard to notice at first, the two undifferentiated figures in the lower left-hand of the picture, at the corner of the Boulevard du Temple. A bootblack squats down and shines the shoes of a man contrapasso above him; impossible to tell what they’re wearing or what they look like. Obviously no way to ascertain their names or professions. At first they’re hard to recognize as people, these whispers of a figure joined together, eternally preserved by silver-plated copper and mercury vapor; they’re insignificant next to the buildings, elegant Beaux-Arts shops and theaters, wrought iron railings along the streets and chimneys on their mansard roofs. Based on an analysis of the light, Louis Daguerre set up his camera around eight in the morning; leaves are still on trees, so it’s not winter, but otherwise it’s hard to tell what season it is that Paris day in 1838. Whatever their names, it was by accident that they became the first two humans to be photographed. The rhythm of life is hardwired into our DNA. More than forty percent of the human genes that code for proteins

The rhythm of life is hardwired into our DNA. More than forty percent of the human genes that code for proteins  Branagh’s Poirot films occupy an increasingly strange place in the increasingly weird ecosystem: the twenty-first century metroplex. Murder on the Orient Express (2017) entered an economy still starry on the possibilities of IP-mining, as top-grossing films of that year exclusively feature Disney properties and pop culture products as heroes. Death on the Nile (2022) appeared to an industry in the throes of its latest crisis, ravaged both by pandemic-induced closures and delays as well as the burgeoning sense that the terrain of our memories handled at the hands of slick corporate storytelling might not be a sustainable model of cultural dispensation. Indeed, several of the top-grossing films of 2022 feature the same trademarks from five years prior (Batman, Thor, the Minions) while folding in “new” revisitations (Avatar, Top Gun, Puss in Boots). Nile’s release, like so many films shot in the wilderness of late 2019 and early 2020, was pushed and pulled like taffy, a cultural object in search of distribution in an industry increasingly at the mercy of corporate conglomeration, content optimization, and a boring spring towards the moral and artistic middle.

Branagh’s Poirot films occupy an increasingly strange place in the increasingly weird ecosystem: the twenty-first century metroplex. Murder on the Orient Express (2017) entered an economy still starry on the possibilities of IP-mining, as top-grossing films of that year exclusively feature Disney properties and pop culture products as heroes. Death on the Nile (2022) appeared to an industry in the throes of its latest crisis, ravaged both by pandemic-induced closures and delays as well as the burgeoning sense that the terrain of our memories handled at the hands of slick corporate storytelling might not be a sustainable model of cultural dispensation. Indeed, several of the top-grossing films of 2022 feature the same trademarks from five years prior (Batman, Thor, the Minions) while folding in “new” revisitations (Avatar, Top Gun, Puss in Boots). Nile’s release, like so many films shot in the wilderness of late 2019 and early 2020, was pushed and pulled like taffy, a cultural object in search of distribution in an industry increasingly at the mercy of corporate conglomeration, content optimization, and a boring spring towards the moral and artistic middle. Modern biomedicine has, of course, delivered breakthrough treatments over the past century, treatments which have transformed the care of diseases which were once considered incurable. Aspirin for heart attacks. Insulin for diabetes. Potent antibiotics to treat infections caused by highly virulent organisms. These interventions are true marvels of the modern age: they’re safe and effective for conditions that affect millions. We should rightfully celebrate such treatments and work to make them widely and freely available.

Modern biomedicine has, of course, delivered breakthrough treatments over the past century, treatments which have transformed the care of diseases which were once considered incurable. Aspirin for heart attacks. Insulin for diabetes. Potent antibiotics to treat infections caused by highly virulent organisms. These interventions are true marvels of the modern age: they’re safe and effective for conditions that affect millions. We should rightfully celebrate such treatments and work to make them widely and freely available.