Peter DeScioli in Psychology Today:

Laws may seem unlikely to come from evolution. There are so many laws, and they differ so much across societies. This variation shows that natural selection did not install a single code of laws in the human mind. We do not have 10 commandments, or five or 20, etched into our minds, or else we would see the same code of laws repeated in society after society.

Laws may seem unlikely to come from evolution. There are so many laws, and they differ so much across societies. This variation shows that natural selection did not install a single code of laws in the human mind. We do not have 10 commandments, or five or 20, etched into our minds, or else we would see the same code of laws repeated in society after society.

But does this mean that human evolution has little to tell us about the origin of laws? Not at all. To see why, just compare laws to tools. Humans make countless tools, and tools vary tremendously across societies. Yet, it is well-understood that humans evolved adaptations to make and use tools. The human mind does not have a fixed set of blueprints for 10 or 20 tools.

More here.

Last month, President Joe Biden issued an

Last month, President Joe Biden issued an  In the church of my childhood, we believed God’s angels battled demons in a war for our souls. This was not a metaphor. We were Pentecostals, though not strictly and not always. We weren’t picky about denomination; what mattered was belief in the redeeming blood of Christ, in the Bible literally interpreted and in God’s endless love. And evil. We believed in evil.

In the church of my childhood, we believed God’s angels battled demons in a war for our souls. This was not a metaphor. We were Pentecostals, though not strictly and not always. We weren’t picky about denomination; what mattered was belief in the redeeming blood of Christ, in the Bible literally interpreted and in God’s endless love. And evil. We believed in evil. In many of Albert Bierstadt’s Western paintings, there is a darkness on one side, maybe a mountain or its shadow. Then toward the middle, animals graze or drink from a lake or stream. And then at the far right or in the sky, splashes of light lie like shawls across the shoulders of the mountains. The great darkness says to me what I often say to heartbroken friends — “I don’t know.”

In many of Albert Bierstadt’s Western paintings, there is a darkness on one side, maybe a mountain or its shadow. Then toward the middle, animals graze or drink from a lake or stream. And then at the far right or in the sky, splashes of light lie like shawls across the shoulders of the mountains. The great darkness says to me what I often say to heartbroken friends — “I don’t know.” There’s a video of Gal Gadot having sex with her stepbrother on the internet.” With that sentence, written by the journalist Samantha Cole for the tech site Motherboard in December, 2017, a queasy new chapter in our cultural history opened. A programmer calling himself “deepfakes” told Cole that he’d used artificial intelligence to insert Gadot’s face into a pornographic video. And he’d made others: clips altered to feature Aubrey Plaza, Scarlett Johansson, Maisie Williams, and Taylor Swift.

There’s a video of Gal Gadot having sex with her stepbrother on the internet.” With that sentence, written by the journalist Samantha Cole for the tech site Motherboard in December, 2017, a queasy new chapter in our cultural history opened. A programmer calling himself “deepfakes” told Cole that he’d used artificial intelligence to insert Gadot’s face into a pornographic video. And he’d made others: clips altered to feature Aubrey Plaza, Scarlett Johansson, Maisie Williams, and Taylor Swift. In mathematics, simple rules can unlock universes of complexity and beauty. Take the famous Fibonacci sequence, which is defined as follows: It begins with 1 and 1, and each subsequent number is the sum of the previous two. The first few numbers are:

In mathematics, simple rules can unlock universes of complexity and beauty. Take the famous Fibonacci sequence, which is defined as follows: It begins with 1 and 1, and each subsequent number is the sum of the previous two. The first few numbers are: In

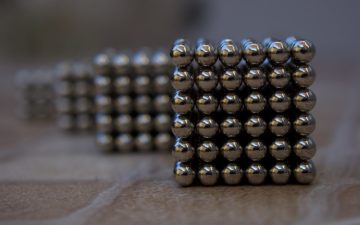

In  We have been through a radical shift in technology across just three generations of my family, and each step of the way has changed our lives dramatically, just as they did for society as a whole: allowing us to communicate with our loved ones, creating the world of instant news, changing the way we work, and altering the way we entertain and are entertained. But while a video call may seem a far cry from the telegram, all these forms of modern communication are based on the science of signals being sent from one distant point to another, almost instantaneously. And our ability to do that centers around magnets.

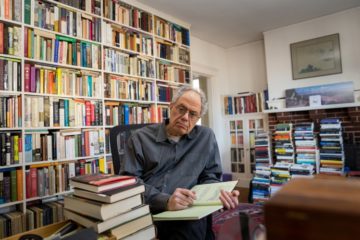

We have been through a radical shift in technology across just three generations of my family, and each step of the way has changed our lives dramatically, just as they did for society as a whole: allowing us to communicate with our loved ones, creating the world of instant news, changing the way we work, and altering the way we entertain and are entertained. But while a video call may seem a far cry from the telegram, all these forms of modern communication are based on the science of signals being sent from one distant point to another, almost instantaneously. And our ability to do that centers around magnets. In an essay on the voluble New York intellectual Dwight Macdonald, George Scialabba cites Lionel Trilling’s assessment of Orwell, who, for Trilling, exemplified “the virtue of not being a genius, of fronting the world with nothing more than one’s simple, direct, undeceived intelligence, and a respect for the powers one does have, and the work one undertakes to do.”

In an essay on the voluble New York intellectual Dwight Macdonald, George Scialabba cites Lionel Trilling’s assessment of Orwell, who, for Trilling, exemplified “the virtue of not being a genius, of fronting the world with nothing more than one’s simple, direct, undeceived intelligence, and a respect for the powers one does have, and the work one undertakes to do.” Like printed books, perspective drawing, and double-entry bookkeeping, pockets were heralds of the modern era. In most times and places, people have either carried their money, combs, papers, and other small items in bags separate from their garments or tucked them into belts or sleeves. Integrated pockets are a product of European tailoring, which dates back only to the 14th century. They emerged when men’s breeches ballooned in the mid-1500s.

Like printed books, perspective drawing, and double-entry bookkeeping, pockets were heralds of the modern era. In most times and places, people have either carried their money, combs, papers, and other small items in bags separate from their garments or tucked them into belts or sleeves. Integrated pockets are a product of European tailoring, which dates back only to the 14th century. They emerged when men’s breeches ballooned in the mid-1500s.

T

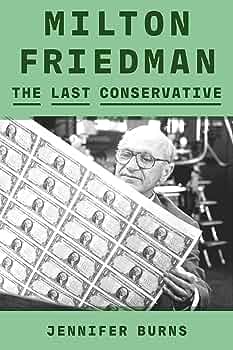

T In writing her new biography of the Nobel Prize-winning economist Milton Friedman, known throughout his long life for his cheerful endorsement of deregulation and free markets, Jennifer Burns certainly had her work cut out for her. Reflecting on how controversial her subject was, she says that one of her goals was “to restore the fullness of Friedman’s thought to his public image.” She depicts Friedman, who

In writing her new biography of the Nobel Prize-winning economist Milton Friedman, known throughout his long life for his cheerful endorsement of deregulation and free markets, Jennifer Burns certainly had her work cut out for her. Reflecting on how controversial her subject was, she says that one of her goals was “to restore the fullness of Friedman’s thought to his public image.” She depicts Friedman, who