Category: Archives

Can We Imagine a World Without Work?

Rachel Fraser in the Boston Review:

Cleaning, like cooking, childbearing, and breastfeeding, is a paradigm case of reproductive labor. Reproductive labor is a special form of work. It doesn’t itself produce commodities (coffee pots, silicon chips); rather, it’s the form of work that creates and maintains labor power itself, and hence makes the production of commodities possible in the first place. Reproductive labor is low-prestige and (typically) either poorly paid or entirely unwaged. It’s also obstinately feminized: both within the social imaginary and in actual fact, most reproductive labor is done by women. It is perhaps unsurprising, then, that political discussions of work often treat reproductive labor as an afterthought.

Cleaning, like cooking, childbearing, and breastfeeding, is a paradigm case of reproductive labor. Reproductive labor is a special form of work. It doesn’t itself produce commodities (coffee pots, silicon chips); rather, it’s the form of work that creates and maintains labor power itself, and hence makes the production of commodities possible in the first place. Reproductive labor is low-prestige and (typically) either poorly paid or entirely unwaged. It’s also obstinately feminized: both within the social imaginary and in actual fact, most reproductive labor is done by women. It is perhaps unsurprising, then, that political discussions of work often treat reproductive labor as an afterthought.

More here.

The Life and Lies of Charles Dickens

John Mullan in The Guardian:

Two years after Charles Dickens’s death in 1870, his closest friend, John Forster, published the first volume of his Life of Charles Dickens. Based on letters Dickens had written to him and stories he had told him, it was, in effect, an authorised biography. For Dickens buffs, it has always been both a matchless source and an untrustworthy narrative. By Helena Kelly’s account, it is more misleading than the most sceptical biographer has supposed. Far from Forster being Dickens’s hagiographer, he was his dupe. We have always known that Dickens aimed to manage his reputation; as Kelly sees it, this led him to deeper deceit than anyone has previously imagined.

Two years after Charles Dickens’s death in 1870, his closest friend, John Forster, published the first volume of his Life of Charles Dickens. Based on letters Dickens had written to him and stories he had told him, it was, in effect, an authorised biography. For Dickens buffs, it has always been both a matchless source and an untrustworthy narrative. By Helena Kelly’s account, it is more misleading than the most sceptical biographer has supposed. Far from Forster being Dickens’s hagiographer, he was his dupe. We have always known that Dickens aimed to manage his reputation; as Kelly sees it, this led him to deeper deceit than anyone has previously imagined.

So, for instance, Forster was the first to make public what Dickens said was the most crushing experience of his life: being sent, aged 12, to work in a blacking warehouse. It was an experience that he handed on to the young protagonist of David Copperfield. “It is wonderful to me how I could have been so easily cast away at such an age,” Dickens wrote, in the account Forster quoted. Yet Kelly picks at some inconsistencies about dates to suppose that it was all fiction. Dickens wanted us to believe he had been neglected and mistreated: it made for a great story of triumph over adversity.

More here.

This Thanksgiving, remember gratitude is key to making democracy work

Editorial Board of The Washington Post:

And yet people are not in a blessing-counting mood, if the polls are to be believed. Only 25 percent of the public believes the country is “on the right track,” according to a RealClearPolitics polling average, whereas 66 percent say the opposite. Voters seem to be giving President Biden little or no credit for the modicum of economic and geopolitical stability over which he has presided. Worse, the latest indications are that about half of voters are so unhappy with the way things are that they might vote next November for former president Donald Trump, a man so obsessed with his own grievances, and so skilled at manipulating the grievances of others, that he pushed this democracy into a violent crisis on Jan. 6, 2021.

More here.

Thursday Poem

Give Me This

I thought it was the neighbor’s cat back

to clean the clock of the fledgling robins low

in their nest stuck in the dense hedge by the house

but what came was much stranger, a liquidity

moving all muscle and bristle. A groundhog

slippery and waddle thieving my tomatoes still

green in the morning’s shade. I watched her

munch and stand on her haunches taking such

pleasure in the watery bites. Why am I not allowed

delight? A stranger writes to request my thoughts

on suffering. Barbed wire pulled out of the mouth,

as if demanding that I kneel to the trap of coiled

spikes used in warfare and fencing. Instead,

I watch the groundhog closer and a sound escapes

me, a small spasm of joy I did not imagine

when I woke. She is a funny creature and earnest,

and she is doing what she can to survive.

by Ada Limón

from Poets.org

Wednesday, November 22, 2023

The Diva Speaks—at Length

Claude R. Marx at The Common Reader:

When describing her directing philosophy, Barbra Streisand has said that less is often more. Unfortunately, she did not take that to heart when writing her long-awaited memoir, My Name is Barbra, which clocks in at over 900 pages.

When describing her directing philosophy, Barbra Streisand has said that less is often more. Unfortunately, she did not take that to heart when writing her long-awaited memoir, My Name is Barbra, which clocks in at over 900 pages.

It covers a great deal of professional and personal ground and has plenty of engaging and revelatory material. But you must wade through too much long-winded prose to get there.

Do you really need three chapters on the making of Yentl (1983)?

The film, about a young Orthodox Jewish girl who disguises herself as a man so she can be allowed to study in a yeshiva, was meaningful and engaging. However, nobody will confuse it with Citizen Kane (1941). Yet there is almost a blow-by-blow description of the writing and directing process that will likely be of interest primarily to students of the craft.

More here.

OpenAI and the Biggest Threat in the History of Humanity

Tomas Pueyo in Uncharted Territories:

AGI is Artificial General Intelligence: a machine that can do nearly anything any human can do: anything mental, and through robots, anything physical. This includes deciding what it wants to do and then executing it, with the thoughtfulness of a human, at the speed and precision of a machine.

AGI is Artificial General Intelligence: a machine that can do nearly anything any human can do: anything mental, and through robots, anything physical. This includes deciding what it wants to do and then executing it, with the thoughtfulness of a human, at the speed and precision of a machine.

Here’s the issue: If you can do anything that a human can do, that includes working on computer engineering to improve yourself. And since you’re a machine, you can do it at the speed and precision of a machine, not a human. You don’t need to go to pee, sleep, or eat. You can create 50 versions of yourself, and have them talk to each other not with words, but with data flows that go thousands of times faster. So in a matter of days—maybe hours, or seconds—you will not be as intelligent as a human anymore, but slightly more intelligent. Since you’re more intelligent, you can improve yourself slightly faster, and become even more intelligent. The more you improve yourself, the faster you improve yourself. Within a few cycles, you develop the intelligence of a God.

More here.

Cass R. Sunstein: Why I Am a Liberal

Cass R. Sunstein in the New York Times:

More than at any other time since World War II, liberalism is under siege. On the left, some people insist that liberalism is exhausted and dying and unable to handle the problems posed by entrenched inequalities, corporate power and environmental degradation. On the right, some people think that liberalism is responsible for the collapse of traditional values, rampant criminality, disrespect for authority and widespread immorality.

More than at any other time since World War II, liberalism is under siege. On the left, some people insist that liberalism is exhausted and dying and unable to handle the problems posed by entrenched inequalities, corporate power and environmental degradation. On the right, some people think that liberalism is responsible for the collapse of traditional values, rampant criminality, disrespect for authority and widespread immorality.

Fascists reject liberalism. So do populists who think that freedom is overrated.

In ways large and small, antiliberalism is on the march. So is tyranny.

Many of the marchers misdescribe liberalism; they offer a caricature. Perhaps more than ever, there is an urgent need for a clear understanding of liberalism — of its core commitments, of its breadth, of its internal debates, of its evolving character, of its promise, of what it is and what it can be.

More here.

Sam Altman returns as OpenAI CEO less than a week after he was fired by board

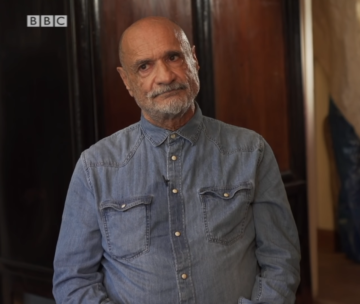

The Art Of Fereydoun Ave

Media Farzin at Artforum:

Ave had started making photocollages of wrestlers in the late ’90s, titling them after characters from the epic tenth-century Iranian poem the Shahnameh (Book of Kings). His main protagonist was Rostam, a warrior of legendary strength and wisdom whom Ave reanimated in images of the young Iranian wrestling champion Abbas Jadidi. In 1996, Jadidi had nearly claimed Olympic gold in Atlanta in an epic match settled by what appeared to be the whims of the American judges—a bit of geopolitical theater, perhaps, at a time when the US was dramatically ramping up sanctions against Iran. Jadidi brought home the silver and went on to win other championships (and enter local politics), but the loss of the gold was deeply felt in a country where wrestling traces its roots to pre-Islamic rites.

Ave had started making photocollages of wrestlers in the late ’90s, titling them after characters from the epic tenth-century Iranian poem the Shahnameh (Book of Kings). His main protagonist was Rostam, a warrior of legendary strength and wisdom whom Ave reanimated in images of the young Iranian wrestling champion Abbas Jadidi. In 1996, Jadidi had nearly claimed Olympic gold in Atlanta in an epic match settled by what appeared to be the whims of the American judges—a bit of geopolitical theater, perhaps, at a time when the US was dramatically ramping up sanctions against Iran. Jadidi brought home the silver and went on to win other championships (and enter local politics), but the loss of the gold was deeply felt in a country where wrestling traces its roots to pre-Islamic rites.

In Jadidi’s sculpted body, Ave saw an emblem of national hope, patriotic hubris, and what he has called the “macho mystique” of Iranian men. (Highlighting the public celebration of scantily dressed young wrestlers was an obliquely polemical critique of the objectification and oppression of women.

more here.

Fereydoun Ave: Tehran in the 1970s

After Melville

Andrew Shenker at The Baffler:

EVERYONE FINDS the Melville they want.

EVERYONE FINDS the Melville they want.

Writing in 2005, Andrew Delbanco observed, in his critical biography Melville: His World and Work, that the author of Moby-Dick “seems to renew himself for each new generation.” Since the mid-twentieth century, Delbanco notes, “there has been a steady stream of new Melvilles, all of whom seem somehow able to keep up with the preoccupations of the moment.” He lists a few:

myth-and-symbol Melville

countercultural Melville

anti-war Melville

environmentalist Melville

gay or bisexual Melville

multicultural Melville

global Melville

And then there’s his deathless creation, Ahab, the man who, per Elizabeth Hardwick, “has no ancestor in literature other than all of literature.” Inspired in part, Delbanco speculates, by former vice president and staunch slavery defender John C. Calhoun, the Pequod’s monomaniacal commander has been likened to everyone from Hitler to the nuclear scientists responsible for the atomic bomb to, inevitably, Donald Trump. (Unless, in a reading popular in right-wing media, Trump is actually the white whale and the Democrats who impeached him are Ahab.)

more here.

Wednesday Poem

When One Has Lived A Long Time Alone

1.

When one has lived a long time alone,

one refrains from swatting the fly

and lets him go, and one hesitates to strike

the mosquito, though more than willing to slap

the flesh under her, and one lifts the toad

from the pit too deep to hop out of

and carries him to the grass, without minding

the poisoned urine he slicks his body with,

and one envelopes, in a towel, the swift

who fell down the chimney and knocks herself

against the window glass and releases her outside

and watches her fly free, a life line flung at reality,

when one has lived a long time alone.

by Galway Kinnell

from When One Has Lived a Long Time Alone

Alfred A, Knoph, New York, 2003

Entire 11 stanza’s: here

‘Breakthrough’ CRISPR Treatment Slashes Cholesterol in First Human Clinical Trial

Shelly Fan in Singularity Hub:

CRISPR-based therapies just hit another milestone. In a small clinical trial with 10 people genetically prone to dangerously high levels of cholesterol, a single infusion of the precision gene editor slashed the artery-clogging fat by up to 55 percent. If all goes well, the one-shot treatment could last a lifetime.

CRISPR-based therapies just hit another milestone. In a small clinical trial with 10 people genetically prone to dangerously high levels of cholesterol, a single infusion of the precision gene editor slashed the artery-clogging fat by up to 55 percent. If all goes well, the one-shot treatment could last a lifetime.

The trial, led by Verve Therapeutics, is the first to explore CRISPR for a chronic disease that’s usually managed with decades of daily pills. It also marks the first use of a newer class of gene editors directly in humans. Called base editing, the technology is more precise—and potentially safer—than the original set of CRISPR tools. The new treatment, VERVE-101, uses a base editor to disable a gene encoding a liver protein that regulates cholesterol.

To be clear, these results are just a sneak peek into the trial, which was designed to test for safety, rather than the treatment’s efficacy. Not all participants responded well. Two people suffered severe heart issues, with one case potentially related to the treatment. Nevertheless, “it is a breakthrough to have shown in humans that in vivo [in the body] base editing works efficiently in the liver,” Dr. Gerald Schwank at the University of Zurich, who wasn’t involved in the trial, told Science.

More here.

Justice for the Palestinians and Security for Israel

Bernie Sanders in The New York Times:

There have been five wars in the last 15 years between Israel and Hamas. How do we end the current one and prevent a sixth from happening, sooner or later? How do we balance our desire to stop the fighting with the need to address the roots of the conflict? For 75 years, diplomats, well-intentioned Israelis and Palestinians and government leaders around the world have struggled to bring peace to this region. In that time an Egyptian president and an Israeli prime minister were assassinated by extremists for their efforts to end the violence.

There have been five wars in the last 15 years between Israel and Hamas. How do we end the current one and prevent a sixth from happening, sooner or later? How do we balance our desire to stop the fighting with the need to address the roots of the conflict? For 75 years, diplomats, well-intentioned Israelis and Palestinians and government leaders around the world have struggled to bring peace to this region. In that time an Egyptian president and an Israeli prime minister were assassinated by extremists for their efforts to end the violence.

And on and on it goes.

For those of us who want not only to bring this war to end, but to avoid a future one, we must first be cleareyed about facts. On Oct. 7, Hamas, a terrorist organization, unleashed a barbaric attack against Israel, killing about 1,200 innocent men, women and children, and taking more than 200 hostages. On a per-capita basis, if Israel had the same population as the United States, that attack would have been the equivalent of nearly 40,000 deaths, more than 10 times the fatalities that we suffered on 9/11.

Israel, in response, under the leadership of its right-wing prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, who is under indictment for corruption and whose cabinet includes outright racists, unleashed what amounts to total war against the Palestinian people. In Gaza, over 1.6 million Palestinians were forced out of their homes. Food, water, medical supplies and fuel were cut off. The United Nations estimates that 45 percent of the housing units in Gaza have been damaged or destroyed. According to the Gaza health ministry, more than 12,000 Palestinians, about half of whom are children, have been killed and many more wounded. And the situation becomes more dire every day.

More here.

Tuesday, November 21, 2023

OpenAI Total Chaos

Anna Cassel’s Prescient Paintings

Johanna Fateman at Bookforum:

IN 1912, THE SWEDISH ARTIST-CLAIRVOYANT Anna Cassel recorded the following message, crystal-clear instructions from a spirit guide, in her diary: “First, allow yourself to have dreams and then visions and colors and numbers, letters and images. Make a careful note of everything. It is of utmost importance to be thorough in your description.” Cassel was a lifelong friend of the spiritualist painter Hilma af Klint (and very likely more than a friend, for a time), as well as a close collaborator. In af Klint’s notebooks, Cassel’s group of 144 enthralling small paintings, her dutifully thorough description of a primordial story, transmitted to her from the astral plane, is referred to as “The Saga of the Rose.” The cycle was meant to serve as both a prayer book for the artists’ devout Christian-occult community (whose all-women initiates totaled just thirteen) and a history of the world. Discovered in the archive of the Swedish Anthroposophical Society in 2021, the sacred illustrations are reproduced in this solemnly beautiful clothbound book, its hushed design aligning with Cassel’s glyphic and celestial compositions. Fastidious and fervent, aware of trends in painting and Modernist decorative arts, Cassel favored botanically inspired lines, distilled geometries, and a crepuscular-or-witching hour palette to capture the strange wind and cold light of a particular metaphysical space.

more here.

Kurt Vonnegut’s House Is Not Haunted

Sophie Kemp at The Paris Review:

In August, I decided to drive to the house for the first time. I did this with my father, because he was the one who gave me Slaughterhouse-Five, and also because he’s now semi-retired and agreed in advance that it would be “funny,” and “cool,” to accompany his twenty-seven-year-old daughter on a “reporting trip” four miles down the road from his house. “Did you know he lived in Schenectady before you moved here?” I asked my father. “No, I don’t think so,” he responded. Out the window: my former elementary school and preschool, the Chinese Fellowship Bible Church, anonymous corporate campuses, new housing developments that when I was a kid were huge, empty fields.

In August, I decided to drive to the house for the first time. I did this with my father, because he was the one who gave me Slaughterhouse-Five, and also because he’s now semi-retired and agreed in advance that it would be “funny,” and “cool,” to accompany his twenty-seven-year-old daughter on a “reporting trip” four miles down the road from his house. “Did you know he lived in Schenectady before you moved here?” I asked my father. “No, I don’t think so,” he responded. Out the window: my former elementary school and preschool, the Chinese Fellowship Bible Church, anonymous corporate campuses, new housing developments that when I was a kid were huge, empty fields.

Vonnegut’s house, which I found by googling “Vonnegut’s house Schenectady NY,” is set directly overlooking Alplaus Creek, on a quiet side street. It is kind of in the woods. Lots of big trees on the street. The houses are old but not old. None of them are big. A few of them have big campers and ATVs out front, and the occasional snow mobile. Old cowboy boots used as planters and wind chimes. Vonnegut’s house is red, slightly set back from the road. It has seen better days, but it is kind of charmingly shabby, overgrown with plants spilling out of the gutters.

more here.

Tuesday Poem

Failing and Flying

Everyone forgets that Icarus also flew.

It’s the same when love comes to an end,

or the marriage fails and people say

they knew it was a mistake, that everybody

said it would never work. That she was

old enough to know better. But anything

worth doing is worth doing badly.

Like being there by that summer ocean

on the other side of the island while

love was fading out of her, the stars

burning so extravagantly those nights that

anyone could tell you they would never last.

Every morning she was asleep in my bed

like a visitation, the gentleness in her

like antelope standing in the dawn mist.

Each afternoon I watched her coming back

through the hot stoney field after swimming,

the sea light behind her and the huge sky

on the other side of that. Listened to her

while we ate lunch. How can they say

the marriage had failed? Like the people who

came back from Provence (when it was Provence)

and said it was pretty but the food was greasy.

I believe Icarus was not failing as he fell,

but just coming to the end of his triumph.

by Jack Gilbert

from Open Field-Poems from Group 18

Open Field Press, Northampton Ma. 2011

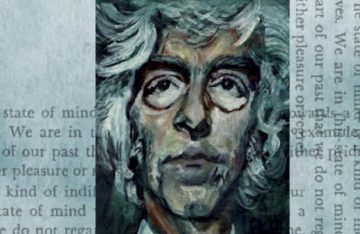

How ideas made Derek Parfit

Paul Nedelisky in The Hedgehog Review:

In 2007, the American philosopher Susan Hurley was dying of cancer. Twenty years earlier, she had been the first female fellow of All Souls College, Oxford. While there, she had been romantically involved with her philosopher colleague Derek Parfit. The romance faded but had turned into a deep friendship. Now, aware of her terminal illness, Hurley journeyed back to Oxford to say goodbye. Hurley and a mutual friend, Bill Ewald, asked Parfit to go to dinner with them. Parfit—by then an esteemed ethicist—refused to join them, protesting that he was too busy with his book manuscript, which concerned “what matters.” Saddened but undeterred, Hurley and Ewald stopped by Parfit’s rooms after dinner so that Hurley could still make her goodbye. Shockingly, Parfit showed them the door, again insisting that he could not spare the time. In truth, he was under no imminent or unalterable deadline. And even if he were, what is a few hours’ tardiness on a deadline compared to a final parting with an old friend? Was this man Parfit some kind of sociopath? Was this perhaps one of those rare but nevertheless possible momentary lapses of moral judgment? Or was he simply a wicked man?

In 2007, the American philosopher Susan Hurley was dying of cancer. Twenty years earlier, she had been the first female fellow of All Souls College, Oxford. While there, she had been romantically involved with her philosopher colleague Derek Parfit. The romance faded but had turned into a deep friendship. Now, aware of her terminal illness, Hurley journeyed back to Oxford to say goodbye. Hurley and a mutual friend, Bill Ewald, asked Parfit to go to dinner with them. Parfit—by then an esteemed ethicist—refused to join them, protesting that he was too busy with his book manuscript, which concerned “what matters.” Saddened but undeterred, Hurley and Ewald stopped by Parfit’s rooms after dinner so that Hurley could still make her goodbye. Shockingly, Parfit showed them the door, again insisting that he could not spare the time. In truth, he was under no imminent or unalterable deadline. And even if he were, what is a few hours’ tardiness on a deadline compared to a final parting with an old friend? Was this man Parfit some kind of sociopath? Was this perhaps one of those rare but nevertheless possible momentary lapses of moral judgment? Or was he simply a wicked man?

More here.

Another Thanksgiving, another case study in the complex relationship between gratitude and discontent in America. In many respects, a typical U.S. family’s cup runneth over, especially relative to the situations facing families in places such as Ukraine, Gaza, Israel, Venezuela, Afghanistan — the list of poor, oppressed or war-torn nations is long. Macroeconomic data indicates that unemployment is hovering near all-time lows, that inflation is coming down, possibly without a recession, and that

Another Thanksgiving, another case study in the complex relationship between gratitude and discontent in America. In many respects, a typical U.S. family’s cup runneth over, especially relative to the situations facing families in places such as Ukraine, Gaza, Israel, Venezuela, Afghanistan — the list of poor, oppressed or war-torn nations is long. Macroeconomic data indicates that unemployment is hovering near all-time lows, that inflation is coming down, possibly without a recession, and that