Rafia Zakaria in the Times Literary Supplement:

“What, then, shall that language be? One-half of the committee maintain that it should be the English. The other half strongly recommend the Arabic and Sanscrit. The whole question seems to me to be – which language is the best worth knowing?” So asked Lord Macaulay of the British Parliament on February 2, 1835. He went on, of course, to answer his own question; there was no way that the natives of the subcontinent over which they now ruled could be “educated by means of their mother-tongue”, in which “there are no books on any subject that deserve to be compared to our own”. And even if there had been, it did not matter, for English “was pre-eminent even among languages of the West”. English, it was decided, would be the language that would be taught to the natives. By 1837, English replaced Persian as the language of courtrooms and official business in Muslim India and took with it the cultural ascendancy of the Persian speakers.

“What, then, shall that language be? One-half of the committee maintain that it should be the English. The other half strongly recommend the Arabic and Sanscrit. The whole question seems to me to be – which language is the best worth knowing?” So asked Lord Macaulay of the British Parliament on February 2, 1835. He went on, of course, to answer his own question; there was no way that the natives of the subcontinent over which they now ruled could be “educated by means of their mother-tongue”, in which “there are no books on any subject that deserve to be compared to our own”. And even if there had been, it did not matter, for English “was pre-eminent even among languages of the West”. English, it was decided, would be the language that would be taught to the natives. By 1837, English replaced Persian as the language of courtrooms and official business in Muslim India and took with it the cultural ascendancy of the Persian speakers.

This sordid story of tainted beginnings is aptly recounted in Muneeza Shamsie’s Hybrid Tapestries: The development of Pakistani literature in English, which traces the history of an often vexed but always intriguing literary lineage from the nineteenth century until today. It is a tricky tale to tell, not least because the moment of origin is also the moment of imposition and conquest. The development of Pakistani literature is directly linked to those deposed Muslims and their cherished Persian, which adds further flavours of resentment and betrayal to the mixture.

More here.

Philosophers love to hate Ayn Rand. It’s trendy to scoff at any mention of her. One philosopher told me that: ‘No one needs to be exposed to that monster.’ Many propose that she’s not a philosopher at all and should not be taken seriously. The problem is that people are taking her seriously. In some cases, very seriously.

Philosophers love to hate Ayn Rand. It’s trendy to scoff at any mention of her. One philosopher told me that: ‘No one needs to be exposed to that monster.’ Many propose that she’s not a philosopher at all and should not be taken seriously. The problem is that people are taking her seriously. In some cases, very seriously. A HUNDRED-DOLLAR BILL is lying on the ground. An economist walks past it. A friend asks the economist: “Didn’t you see the money there?” The economist replies: “I thought I saw something, but I must have imagined it. If there had been $100 on the ground, someone would have picked it up.”

A HUNDRED-DOLLAR BILL is lying on the ground. An economist walks past it. A friend asks the economist: “Didn’t you see the money there?” The economist replies: “I thought I saw something, but I must have imagined it. If there had been $100 on the ground, someone would have picked it up.” In 1989, a trainee physician called Edward Bullmore treated a woman in her late fifties. Mrs P had swollen joints in her hands and knees. She had an autoimmune disease. Her own immune system had attacked her, flooding her joints with inflammation. This, in turn, had eaten away at Mrs P’s collagen and bone, noted Bullmore, who was 29, and whose real ambition was to become a psychiatrist.

In 1989, a trainee physician called Edward Bullmore treated a woman in her late fifties. Mrs P had swollen joints in her hands and knees. She had an autoimmune disease. Her own immune system had attacked her, flooding her joints with inflammation. This, in turn, had eaten away at Mrs P’s collagen and bone, noted Bullmore, who was 29, and whose real ambition was to become a psychiatrist. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, East German citizens were offered the chance to read the files kept on them by the Stasi, the much-feared Communist-era secret police service. To date, it is estimated that only 10 percent have taken the opportunity. In 2007, James Watson, the co-discoverer of the structure of DNA, asked that he not be given any information about his APOE gene, one allele of which is a known risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease. Most people tell pollsters that, given the choice, they would prefer not to know the date of their own death—or even the future dates of happy events. Each of these is an example of willful ignorance. Socrates may have made the case that the unexamined life is not worth living, and Hobbes may have argued that curiosity is mankind’s primary passion, but many of our oldest stories actually describe the dangers of knowing too much. From Adam and Eve and the tree of knowledge to Prometheus stealing the secret of fire, they teach us that real-life decisions need to strike a delicate balance between choosing to know, and choosing not to.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, East German citizens were offered the chance to read the files kept on them by the Stasi, the much-feared Communist-era secret police service. To date, it is estimated that only 10 percent have taken the opportunity. In 2007, James Watson, the co-discoverer of the structure of DNA, asked that he not be given any information about his APOE gene, one allele of which is a known risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease. Most people tell pollsters that, given the choice, they would prefer not to know the date of their own death—or even the future dates of happy events. Each of these is an example of willful ignorance. Socrates may have made the case that the unexamined life is not worth living, and Hobbes may have argued that curiosity is mankind’s primary passion, but many of our oldest stories actually describe the dangers of knowing too much. From Adam and Eve and the tree of knowledge to Prometheus stealing the secret of fire, they teach us that real-life decisions need to strike a delicate balance between choosing to know, and choosing not to. Surprisingly, few of the world’s great philosophers have directly addressed this question. Instead, they have focused on a subtly different question: what does it mean to live well? In his

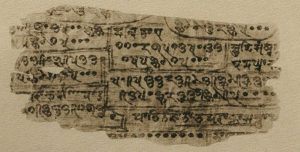

Surprisingly, few of the world’s great philosophers have directly addressed this question. Instead, they have focused on a subtly different question: what does it mean to live well? In his  The Bakhshali manuscript is a mathematical document found in 1881 by a local farmer in the vicinity of the village of Bakhshali, near the city of Peshawar in what was then British India and is now Pakistan. It is written in ink on birch bark, a common medium for manuscripts in northwestern India throughout much of history. In the tough climate of India and neighbouring regions, such things deteriorate rapidly, and it is miraculous that this document has survived.

The Bakhshali manuscript is a mathematical document found in 1881 by a local farmer in the vicinity of the village of Bakhshali, near the city of Peshawar in what was then British India and is now Pakistan. It is written in ink on birch bark, a common medium for manuscripts in northwestern India throughout much of history. In the tough climate of India and neighbouring regions, such things deteriorate rapidly, and it is miraculous that this document has survived. Although he’s older than the Giza pyramids and Stonehenge, the 5,300-year-old mummy of Otzi the Tyrolean Iceman continues to teach us things.

Although he’s older than the Giza pyramids and Stonehenge, the 5,300-year-old mummy of Otzi the Tyrolean Iceman continues to teach us things. On 7 January this year, the alt-right insurgent Steve Bannon turned on his TV in Washington DC to watch the Golden Globes. The mood of the event was sombre. It was the immediate aftermath of multiple accusations of rape and sexual assault against film producer Harvey Weinstein, which he has denied. The women, whose outfits would normally have been elaborate and the subject of frantic scrutiny, wore plain and sober black. In the course of

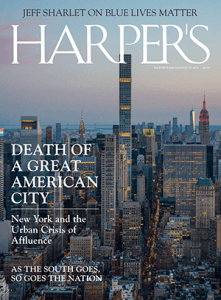

On 7 January this year, the alt-right insurgent Steve Bannon turned on his TV in Washington DC to watch the Golden Globes. The mood of the event was sombre. It was the immediate aftermath of multiple accusations of rape and sexual assault against film producer Harvey Weinstein, which he has denied. The women, whose outfits would normally have been elaborate and the subject of frantic scrutiny, wore plain and sober black. In the course of  As New York enters the third decade of the twenty-first century, it is in imminent danger of becoming something it has never been before: unremarkable. It is approaching a state where it is no longer a significant cultural entity but the world’s largest gated community, with a few cupcake shops here and there. For the first time in its history, New York is, well, boring.

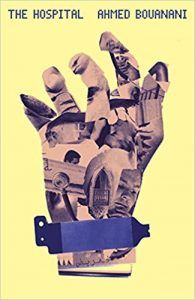

As New York enters the third decade of the twenty-first century, it is in imminent danger of becoming something it has never been before: unremarkable. It is approaching a state where it is no longer a significant cultural entity but the world’s largest gated community, with a few cupcake shops here and there. For the first time in its history, New York is, well, boring. Like Bouanani’s memories of his childhood rue de Monastir, The Hospital is fastened securely to Morocco, even if it floats above it in a haze of time and space. Vergnaud expresses this endemic connection between lexicon and place succinctly: “The taxonomy of flora and fauna, smells and tastes, saints and legends permeates The Hospital,” she writes, meaning of course the one in Bouanani’s novel, and Bouanani’s novel itself. “With amnesia as the disease, and time itself in question, Bouanani delights in naming things—weeping willows and cyclamen flowers, prickly pears and esparto grass, Sidi bel Abbas and the two-horned Alexander—to anchor his character’s memories and dream lives.” Vergnaud’s lexical choices in these instances affect her reader in a slightly different way that do Bouanani’s, as the local implications can’t necessary cross the gap, but in the end, the result is quite similar: these precisely vague choices tie us to a Morocco we can’t reach, much as they connect the in-patients to a Morocco that is fragmentary, inaccessible, and lost in the past.

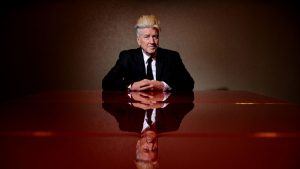

Like Bouanani’s memories of his childhood rue de Monastir, The Hospital is fastened securely to Morocco, even if it floats above it in a haze of time and space. Vergnaud expresses this endemic connection between lexicon and place succinctly: “The taxonomy of flora and fauna, smells and tastes, saints and legends permeates The Hospital,” she writes, meaning of course the one in Bouanani’s novel, and Bouanani’s novel itself. “With amnesia as the disease, and time itself in question, Bouanani delights in naming things—weeping willows and cyclamen flowers, prickly pears and esparto grass, Sidi bel Abbas and the two-horned Alexander—to anchor his character’s memories and dream lives.” Vergnaud’s lexical choices in these instances affect her reader in a slightly different way that do Bouanani’s, as the local implications can’t necessary cross the gap, but in the end, the result is quite similar: these precisely vague choices tie us to a Morocco we can’t reach, much as they connect the in-patients to a Morocco that is fragmentary, inaccessible, and lost in the past. The book gives us a glimpse not only into Lynch, the man and the artist, but also into Lynch’s America — the place the man came from, the space the artist depicts. “In Lynch’s realm,” McKenna writes, “America is like a river that flows ever forward, carrying odds and ends from one decade into the next, where they intermingle and blur dividing lines we’ve invented to mark time.” Lynch’s America is dream-like, uncanny, full of mystery, full of madness, ever-askew.

The book gives us a glimpse not only into Lynch, the man and the artist, but also into Lynch’s America — the place the man came from, the space the artist depicts. “In Lynch’s realm,” McKenna writes, “America is like a river that flows ever forward, carrying odds and ends from one decade into the next, where they intermingle and blur dividing lines we’ve invented to mark time.” Lynch’s America is dream-like, uncanny, full of mystery, full of madness, ever-askew. The internet has for some time hummed with anxious murmuring about the Singularity. The rate of technological progress is accelerating exponentially; the Singularity refers to the moment when computers have become so smart that they escape our control and eventually become super-intelligences capable of stamping out humans like so much vermin. Those tuned into news of the coming catastrophe keep a beady eye on IBM, whose scientists are doing all they can to ensure their own survival as obsequious quislings to our future mechanical overlords. On Tuesday, the company announced that it had brought us one step closer to “real AI” (an intelligence as smart as a human) with its snappily named Project Debater: a supercomputer dedicated to the art of competitive debating. After years of research, this week it finally competed against two real-life human debaters. The result? A thumping one-all draw – according to an audience that I suspect was almost entirely made up of people who thought that HAL, the genial yet murderous computer in “2001: A Space Odyssey”, was the real hero of the film.

The internet has for some time hummed with anxious murmuring about the Singularity. The rate of technological progress is accelerating exponentially; the Singularity refers to the moment when computers have become so smart that they escape our control and eventually become super-intelligences capable of stamping out humans like so much vermin. Those tuned into news of the coming catastrophe keep a beady eye on IBM, whose scientists are doing all they can to ensure their own survival as obsequious quislings to our future mechanical overlords. On Tuesday, the company announced that it had brought us one step closer to “real AI” (an intelligence as smart as a human) with its snappily named Project Debater: a supercomputer dedicated to the art of competitive debating. After years of research, this week it finally competed against two real-life human debaters. The result? A thumping one-all draw – according to an audience that I suspect was almost entirely made up of people who thought that HAL, the genial yet murderous computer in “2001: A Space Odyssey”, was the real hero of the film. When “Go Set a Watchman” was published in 2015, an Alabama lawyer called me with a catch in his voice. Had I heard that his hero Atticus Finch had an evil twin? Unlike the virtuous lawyer who saved an innocent black man from a lynch mob in “To Kill a Mockingbird,” the segregationist Atticus organized the white citizens council, figuratively speaking, in Boo Radley’s peaceful backyard. Three years later, my friend still believes that Harper Lee was tricked, in her dotage, into shredding the image of perhaps the only white Alabamian other than Helen Keller to be admired around the world. Never mind that this better Atticus is fictional; my home state has learned to grab admiration where it can.

When “Go Set a Watchman” was published in 2015, an Alabama lawyer called me with a catch in his voice. Had I heard that his hero Atticus Finch had an evil twin? Unlike the virtuous lawyer who saved an innocent black man from a lynch mob in “To Kill a Mockingbird,” the segregationist Atticus organized the white citizens council, figuratively speaking, in Boo Radley’s peaceful backyard. Three years later, my friend still believes that Harper Lee was tricked, in her dotage, into shredding the image of perhaps the only white Alabamian other than Helen Keller to be admired around the world. Never mind that this better Atticus is fictional; my home state has learned to grab admiration where it can. Barbara Ehrenreich cuts an unusual figure in American culture. A prominent radical who never became a liberal, a celebrity, or a reactionary, who built a successful career around socialist-feminist writing and activism, she embodies an opportunity that was lost when the New Left went down to defeat. Since the mid-1970s she has devoted her work to an unsparing examination of what she viewed as the self-involvement of her professional, middle-class peers: from their narcissism and superiority in

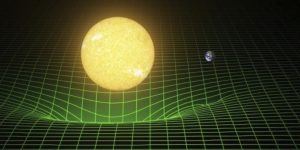

Barbara Ehrenreich cuts an unusual figure in American culture. A prominent radical who never became a liberal, a celebrity, or a reactionary, who built a successful career around socialist-feminist writing and activism, she embodies an opportunity that was lost when the New Left went down to defeat. Since the mid-1970s she has devoted her work to an unsparing examination of what she viewed as the self-involvement of her professional, middle-class peers: from their narcissism and superiority in  In order to test General Relativity as a theory of gravity, you need to find a system where the signal you’ll see differs from other theories of gravity. This must at least include Newton’s theory, but should, ideally, include alternative theories of gravity that make distinct predictions from Einstein’s. Classically, the first such test that did this was right at the edge of the Sun: where gravity is strongest in our Solar System.

In order to test General Relativity as a theory of gravity, you need to find a system where the signal you’ll see differs from other theories of gravity. This must at least include Newton’s theory, but should, ideally, include alternative theories of gravity that make distinct predictions from Einstein’s. Classically, the first such test that did this was right at the edge of the Sun: where gravity is strongest in our Solar System.