Daniel Friedman in Quillette:

In an expert analysis commissioned to defend Harvard’s admissions practices against a lawsuit, claiming the elite university discriminates against Asian-American applicants, economist David Card explains that the school uses a complicated multivariate analysis that balances applicants’ academic records with a host of other factors.

In an expert analysis commissioned to defend Harvard’s admissions practices against a lawsuit, claiming the elite university discriminates against Asian-American applicants, economist David Card explains that the school uses a complicated multivariate analysis that balances applicants’ academic records with a host of other factors.

Asian Americans are significantly overrepresented among the highest-scoring college applicants in the United States. And an internal Harvard study from 2013 determined that, if admissions committees only considered academic qualifications, the proportion of Asians among Harvard students would rise from about 19 percent to about 43 percent. However, Harvard admissions officials contend that Asians have lower scores on measures of personality, including items for courage, likability, kindness and being “widely respected.”

Card’s analysis shows that while Asians are disproportionately represented among the highest academic achievers, white applicants are more likely to score higher on the personality factors, and more likely to be considered multifaceted applicants. But is Harvard really choosing multifaceted white people with sparkling personalities over one-dimensional Asian academic grinds? Or are scores for “likability” and “kindness” really proxies for other qualities that Harvard doesn’t want to admit are admissions factors?

Who has the best personalities?

More here.

HALF A CENTURY AGO, when Yukio Mishima’s Sun and Steel was published, reasonable people the world over were entertaining the possibility that a global Marxist revolution really was at hand. Naturally, not everyone was enthused about the prospect. In Japan, where the upheaval was massive, campus demonstrators were regularly attacked by gangs of right-wing phys-ed majors wielding sports equipment. Administrators at Tokyo’s Nihon University at one point publicly requested the help of these reactionary jocks in quelling student unrest. Mishima (1925–70), a reactionary jock himself, was appalled by the demonstrations and by the New Left in general, but bashing people on the head with golf clubs was not his style. Sun and Steel—billed by the author as a “personal history,” but really more of a philosophical tract—has the unhurried cadences of the long game. Mishima was dreaming of imperial restoration, a rewinding not only of the 1960s but also of Bretton Woods, the whole postwar geopolitical order, and, possibly, political modernity tout court. Many contemporary readers of Sun and Steel harbor analogous ambitions. A minor work in the context of world literature, it is a major one in the bizarro universe of white-supremacist arts and letters.

HALF A CENTURY AGO, when Yukio Mishima’s Sun and Steel was published, reasonable people the world over were entertaining the possibility that a global Marxist revolution really was at hand. Naturally, not everyone was enthused about the prospect. In Japan, where the upheaval was massive, campus demonstrators were regularly attacked by gangs of right-wing phys-ed majors wielding sports equipment. Administrators at Tokyo’s Nihon University at one point publicly requested the help of these reactionary jocks in quelling student unrest. Mishima (1925–70), a reactionary jock himself, was appalled by the demonstrations and by the New Left in general, but bashing people on the head with golf clubs was not his style. Sun and Steel—billed by the author as a “personal history,” but really more of a philosophical tract—has the unhurried cadences of the long game. Mishima was dreaming of imperial restoration, a rewinding not only of the 1960s but also of Bretton Woods, the whole postwar geopolitical order, and, possibly, political modernity tout court. Many contemporary readers of Sun and Steel harbor analogous ambitions. A minor work in the context of world literature, it is a major one in the bizarro universe of white-supremacist arts and letters. But here is the real reason I hate asterisks.

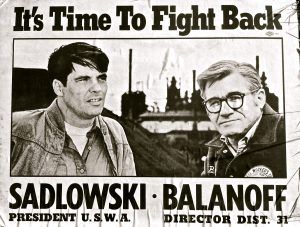

But here is the real reason I hate asterisks. Sadlowski embodied the wish for organized labor to wake from its postwar slumber and again throw its weight behind a great movement for a different country, as it had done in the 1930s and before. The AFL-CIO had shamefully backed the Vietnam War; Sadlowski opposed it and denounced the growth of “the weapons economy”—of which steel was very much a part. Many of the unions in the federation, including the USWA, had dragged their heels at best on racial integration of their workplaces; Sadlowski called for strengthening the union’s civil rights apparatus, attracting the support of Jesse Jackson and members of the Coalition of Black Trade Unionists. Much of organized labor met environmentalism with hostility; Sadlowski dissented. “It’s one hell of a thing for me to say—we just don’t need any more steel mills. We don’t need that kind of industrial growth, at the expense of what the environment should be.” He followed the thought where it led: “Enough with the car!” What more radical claim could a blue-collar worker make about postwar society than to doubt the automobile?

Sadlowski embodied the wish for organized labor to wake from its postwar slumber and again throw its weight behind a great movement for a different country, as it had done in the 1930s and before. The AFL-CIO had shamefully backed the Vietnam War; Sadlowski opposed it and denounced the growth of “the weapons economy”—of which steel was very much a part. Many of the unions in the federation, including the USWA, had dragged their heels at best on racial integration of their workplaces; Sadlowski called for strengthening the union’s civil rights apparatus, attracting the support of Jesse Jackson and members of the Coalition of Black Trade Unionists. Much of organized labor met environmentalism with hostility; Sadlowski dissented. “It’s one hell of a thing for me to say—we just don’t need any more steel mills. We don’t need that kind of industrial growth, at the expense of what the environment should be.” He followed the thought where it led: “Enough with the car!” What more radical claim could a blue-collar worker make about postwar society than to doubt the automobile? Contrary to the proverbial tree-falling-in-the forest quandary, a musical note that fails to materialize is at least as present in our brain as it would be had it actually sounded. That’s because neural substrates of imagined sound correlate with those of perceived external sounds. The more vivid the image of what must happen, the more jarring it is when that certainty is subverted.

Contrary to the proverbial tree-falling-in-the forest quandary, a musical note that fails to materialize is at least as present in our brain as it would be had it actually sounded. That’s because neural substrates of imagined sound correlate with those of perceived external sounds. The more vivid the image of what must happen, the more jarring it is when that certainty is subverted. Arundhati Roy does not believe in rushing things.

Arundhati Roy does not believe in rushing things.

On her Goop website, Gwyneth Paltrow claimed that charcoal lemonade was one of the

On her Goop website, Gwyneth Paltrow claimed that charcoal lemonade was one of the  In the months leading up to Monday’s

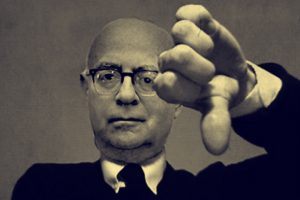

In the months leading up to Monday’s It’s no insult to the late Stanley Cavell, whose death at age 91 was announced on Tuesday, that he was the rare philosopher who was read as much for his prose as for his ideas. Although Cavell had all the right academic credentials — he taught at Harvard for many years and was a distinguished advocate for the “ordinary language philosophy” of J.L. Austin — his books were written with an eccentric, sometimes maddening, elan. Cavell’s sentences were alive with allusions in hectic smart-alecky self-mocking prose that seem closer in spirit to a Marx Brothers movie than a philosophic tome.

It’s no insult to the late Stanley Cavell, whose death at age 91 was announced on Tuesday, that he was the rare philosopher who was read as much for his prose as for his ideas. Although Cavell had all the right academic credentials — he taught at Harvard for many years and was a distinguished advocate for the “ordinary language philosophy” of J.L. Austin — his books were written with an eccentric, sometimes maddening, elan. Cavell’s sentences were alive with allusions in hectic smart-alecky self-mocking prose that seem closer in spirit to a Marx Brothers movie than a philosophic tome. Back in the 1970s, Raymond Geuss was a young colleague of Richard Rorty in the mighty philosophy department at Princeton. In some ways they were very different: Rorty was a middle-class New Yorker with a talent for reckless generalization, whereas Geuss was a fastidious scholar-poet from working-class Pennsylvania. But they shared a commitment to left-wing politics, and both of them dissented from the mainstream view of philosophy as a unified discipline advancing majestically towards absolute knowledge. For a while, Rorty and Geuss could bond as the bad boys of Princeton.

Back in the 1970s, Raymond Geuss was a young colleague of Richard Rorty in the mighty philosophy department at Princeton. In some ways they were very different: Rorty was a middle-class New Yorker with a talent for reckless generalization, whereas Geuss was a fastidious scholar-poet from working-class Pennsylvania. But they shared a commitment to left-wing politics, and both of them dissented from the mainstream view of philosophy as a unified discipline advancing majestically towards absolute knowledge. For a while, Rorty and Geuss could bond as the bad boys of Princeton. Faced with the oncoming Iranian player, Vahid Amiri, Iniesta opened his hips, as if he were preparing to pass the ball to his teammate on the touchline. The pop star Shakira,

Faced with the oncoming Iranian player, Vahid Amiri, Iniesta opened his hips, as if he were preparing to pass the ball to his teammate on the touchline. The pop star Shakira,  The presidents of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine issued a

The presidents of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine issued a  After 18 months of Trump in the White House, American politics finds itself at a crossroads. The United States has moved unmistakably toward a novel form of fascism that serves exclusively corporate interests and the military, while promoting at the same time a highly reactionary social agenda infused with religious and crude nationalistic overtones, all with an uncanny touch of political showmanship. In this exclusive Truthout interview, world-renowned linguist and public intellectual Noam Chomsky analyzes some of the latest developments in Trumpistan and their consequences for democracy and world order.

After 18 months of Trump in the White House, American politics finds itself at a crossroads. The United States has moved unmistakably toward a novel form of fascism that serves exclusively corporate interests and the military, while promoting at the same time a highly reactionary social agenda infused with religious and crude nationalistic overtones, all with an uncanny touch of political showmanship. In this exclusive Truthout interview, world-renowned linguist and public intellectual Noam Chomsky analyzes some of the latest developments in Trumpistan and their consequences for democracy and world order. Big banks are skirting the rules on the sale of the complex financial instruments that helped bring about the 2008 financial crisis, by exploiting a loophole in federal banking regulations,

Big banks are skirting the rules on the sale of the complex financial instruments that helped bring about the 2008 financial crisis, by exploiting a loophole in federal banking regulations,  In hindsight, our son was gearing up to wear a dress to school for quite some time. For months, he wore dresses—or his purple-and-green mermaid costume—on weekends and after school. Then he began wearing them to sleep in lieu of pajamas, changing out of them after breakfast. Finally, one morning, I brought him his clean pants and shirt, and he looked at me and said, “I’m already dressed.”

In hindsight, our son was gearing up to wear a dress to school for quite some time. For months, he wore dresses—or his purple-and-green mermaid costume—on weekends and after school. Then he began wearing them to sleep in lieu of pajamas, changing out of them after breakfast. Finally, one morning, I brought him his clean pants and shirt, and he looked at me and said, “I’m already dressed.”