Daniel McCarthy in The National Interest:

Today, liberalism appears to be dying in much the same way that Soviet Communism did a generation ago. It is collapsing on its periphery, shedding its colonies and facing a crisis of faith at home. History has gone into reverse in the realm of the old Warsaw Pact, first with Russia, now Hungary, Poland and the former East Germany rejecting liberalism—just as they did Marxism three decades ago. The exotic American orchid of liberal democracy, having taken root in such unlikely climes as postwar Germany and Japan, has failed to flower where the Iron Curtain once cast its shadow.

Today, liberalism appears to be dying in much the same way that Soviet Communism did a generation ago. It is collapsing on its periphery, shedding its colonies and facing a crisis of faith at home. History has gone into reverse in the realm of the old Warsaw Pact, first with Russia, now Hungary, Poland and the former East Germany rejecting liberalism—just as they did Marxism three decades ago. The exotic American orchid of liberal democracy, having taken root in such unlikely climes as postwar Germany and Japan, has failed to flower where the Iron Curtain once cast its shadow.

The story is the same elsewhere: a new sort of decolonization is taking place from the Eastern Mediterranean to South Asia. States that until recently aspired to Western-style modernity on their own terms now find little need for the secular models of liberalism or socialism. They have taken up instead the old cause of faith and nation.

Bitter rivals though they may have been, liberalism and Communism sprang from a common nineteenth-century vision of human destiny: of a future that was secularizing, scientific, materially prosperous, progressive, universal and inevitable. This, for all its variations, was the vision of Vladimir Lenin and Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, David Ben-Gurion and Jawaharlal Nehru, Woodrow Wilson and the architects of the European Union. The decline of liberalism is not a surprise twist to history, seen in this light. It is only a continuation of what destroyed the Soviet order—a long awakening from the utopian reverie of scientific truth wedded to power.

More here. [Thanks to Omar Ali.]

Wealth inequality is one of the great moral issues of our time. In an era when the world has more money than ever before, billions still live on less than $3 a day. The disparity becomes more striking in the light of studies that show

Wealth inequality is one of the great moral issues of our time. In an era when the world has more money than ever before, billions still live on less than $3 a day. The disparity becomes more striking in the light of studies that show  He must have been a nightmarish visitor for museum staff to deal with because he had a constant urge to touch sculpture, to internalise the shape of an object by feeling it. At Meudon, an observer noted ‘how his fingers tremble when he touches these old stones.’ London was a haven for Rodin: ‘Your beautiful museums, with their marvellous collections, Greek, Assyrian, and Egyptian, awaked in me a flood of sensations, which, if not new, had at any rate a rejuvenating influence; and those sensations caused me to follow Nature all the more closely in my studies.’

He must have been a nightmarish visitor for museum staff to deal with because he had a constant urge to touch sculpture, to internalise the shape of an object by feeling it. At Meudon, an observer noted ‘how his fingers tremble when he touches these old stones.’ London was a haven for Rodin: ‘Your beautiful museums, with their marvellous collections, Greek, Assyrian, and Egyptian, awaked in me a flood of sensations, which, if not new, had at any rate a rejuvenating influence; and those sensations caused me to follow Nature all the more closely in my studies.’ LOOK, THERE’S NO HARD-AND-FAST RULE

LOOK, THERE’S NO HARD-AND-FAST RULE TM: All three of these plays spring from very specific moments in Detroit’s history. Detroit ’67, of course, was the bloody summer of 1967. Skeleton Crew was in 2008, when General Motors and the city were about to go bankrupt. And now Paradise Blue is set in 1949. When we talked before, you told me you’re not writing history, even though the city’s history is very much a part of your plays. What exactly are you writing?

TM: All three of these plays spring from very specific moments in Detroit’s history. Detroit ’67, of course, was the bloody summer of 1967. Skeleton Crew was in 2008, when General Motors and the city were about to go bankrupt. And now Paradise Blue is set in 1949. When we talked before, you told me you’re not writing history, even though the city’s history is very much a part of your plays. What exactly are you writing? When an adult striped dolphin emerged from the Mediterranean Sea in 2016 pushing, nudging, and circling the carcass of its dead female companion for more than an hour, a nearby boat of scientists fell silent. Afterward, the students aboard said they were certain the dolphin was grieving. But was this grief or some other response? In a new study, researchers are attempting to get to the bottom of a mystery that has plagued behavioral biologists for 50 years.

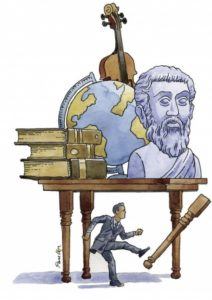

When an adult striped dolphin emerged from the Mediterranean Sea in 2016 pushing, nudging, and circling the carcass of its dead female companion for more than an hour, a nearby boat of scientists fell silent. Afterward, the students aboard said they were certain the dolphin was grieving. But was this grief or some other response? In a new study, researchers are attempting to get to the bottom of a mystery that has plagued behavioral biologists for 50 years. The humanities are taking it on the chin. If there were any doubts about this proposition, they have been dispelled by the University of Wisconsin at Stevens Point’s

The humanities are taking it on the chin. If there were any doubts about this proposition, they have been dispelled by the University of Wisconsin at Stevens Point’s  In 2011, the wildlife biologist Justin Brashares and his students set up a series of camera traps in and around Ruaha National Park in southern Tanzania. They were studying the effects of human activities on antelope reproduction, but their cameras soon revealed an odd and far more obvious pattern. While the antelope inside the park were active during the day, those outside the park, closer to human settlements, were active primarily at night—even though lions, which prey on antelope both inside and outside the park, typically hunt at night. The contrast in behavior was so stark that when Brashares and one of his students looked at a plot of the data, they laughed in disbelief. When faced with a choice between humans and lions, it appeared, antelope preferred to tangle with lions, and they were going nocturnal to do so.

In 2011, the wildlife biologist Justin Brashares and his students set up a series of camera traps in and around Ruaha National Park in southern Tanzania. They were studying the effects of human activities on antelope reproduction, but their cameras soon revealed an odd and far more obvious pattern. While the antelope inside the park were active during the day, those outside the park, closer to human settlements, were active primarily at night—even though lions, which prey on antelope both inside and outside the park, typically hunt at night. The contrast in behavior was so stark that when Brashares and one of his students looked at a plot of the data, they laughed in disbelief. When faced with a choice between humans and lions, it appeared, antelope preferred to tangle with lions, and they were going nocturnal to do so. The Austrian émigré writer Stefan Zweig composed the first draft of his memoir, “

The Austrian émigré writer Stefan Zweig composed the first draft of his memoir, “ The US Environmental Protection Agency has, of late, been operating on the principle that you can prevent environmental disasters by simply getting rid of the environment. As part of this mission, the EPA has considered a plan to put climate science up for public debate. This “Red Team, Blue Team” exercise would have pitted scientists against people who do not like them in order to cast doubt on the consensus that human activities are warming the planet. I am completely on board with this, as long as the Blue Team also gets private jets and enormous security details. We will, however, take a pass on the used Trump Hotel mattresses.

The US Environmental Protection Agency has, of late, been operating on the principle that you can prevent environmental disasters by simply getting rid of the environment. As part of this mission, the EPA has considered a plan to put climate science up for public debate. This “Red Team, Blue Team” exercise would have pitted scientists against people who do not like them in order to cast doubt on the consensus that human activities are warming the planet. I am completely on board with this, as long as the Blue Team also gets private jets and enormous security details. We will, however, take a pass on the used Trump Hotel mattresses. In 1998, Watts and Strogatz

In 1998, Watts and Strogatz Political debates in Europe these days seem to have only one subject. At one point or another they all turn to the issue of migration, Islam, and a danger to “the West”, which are presented as essentially synonymous. Germany’s political future seems currently to

Political debates in Europe these days seem to have only one subject. At one point or another they all turn to the issue of migration, Islam, and a danger to “the West”, which are presented as essentially synonymous. Germany’s political future seems currently to

Like has undergone radical developments in modern English. It can function as a hedge (‘I’ll be there in like an hour’), a discourse particle (‘This like serves a pragmatic function’), and a sentence adverb (‘It’s common in Ireland, like’). These and other non-standard usages are frequently criticised, but they’re probably

Like has undergone radical developments in modern English. It can function as a hedge (‘I’ll be there in like an hour’), a discourse particle (‘This like serves a pragmatic function’), and a sentence adverb (‘It’s common in Ireland, like’). These and other non-standard usages are frequently criticised, but they’re probably