Peter Reuell in the Harvard Gazette:

By several measures, including rates of poverty and violence, progress is an international reality. Why, then, do so many of us believe otherwise?

By several measures, including rates of poverty and violence, progress is an international reality. Why, then, do so many of us believe otherwise?

The answer, Harvard researcher Daniel Gilbert says, may lie in “prevalence-induced concept change.”

In a series of studies, Gilbert, the Edgar Pierce Professor of Psychology, his postdoctoral student David Levari, and several other researchers show that as the prevalence of a problem is reduced, humans are inclined to redefine the problem. As a problem becomes smaller, conceptualizations of the problem expand, which can lead to progress being discounted. The research is described in a paper in the June 29 issue of Science.

“Our studies show that people judge each new instance of a concept in the context of the previous instances,” Gilbert said. “So as we reduce the prevalence of a problem, such as discrimination, for example, we judge each new behavior in the improved context that we have created.”

“Another way to say this is that solving problems causes us to expand our definitions of them,” he said. “When problems become rare, we count more things as problems. Our studies suggest that when the world gets better, we become harsher critics of it, and this can cause us to mistakenly conclude that it hasn’t actually gotten better at all. Progress, it seems, tends to mask itself.”

More here.

Here is the predicament that most of us seem to be in. We are not virtuous people. We simply do not have characters that are good enough to qualify as honest, compassionate, wise, courageous, and the like. We are not vicious people either—dishonest, callous, foolish, cowardly, and so forth. Rather we have a mixed character with some good sides and some bad sides. This is the most plausible interpretation of what psychology tells us. It is also true to our lived experience in the world. Those are the facts as I see them. Now comes the value judgment—this is a real shame. It is very unfortunate that our characters are this way. It is a good thing—indeed, a very good thing—to be a good person. Excellence of character, or being virtuous, is what we should all strive for. Admittedly, the news is not all bad. It would be a lot worse if most of us were vicious people. Imagine what it would be like to live in a world full of mostly cruel, self-centered, dishonest, and hateful people. It would be hell on earth.

Here is the predicament that most of us seem to be in. We are not virtuous people. We simply do not have characters that are good enough to qualify as honest, compassionate, wise, courageous, and the like. We are not vicious people either—dishonest, callous, foolish, cowardly, and so forth. Rather we have a mixed character with some good sides and some bad sides. This is the most plausible interpretation of what psychology tells us. It is also true to our lived experience in the world. Those are the facts as I see them. Now comes the value judgment—this is a real shame. It is very unfortunate that our characters are this way. It is a good thing—indeed, a very good thing—to be a good person. Excellence of character, or being virtuous, is what we should all strive for. Admittedly, the news is not all bad. It would be a lot worse if most of us were vicious people. Imagine what it would be like to live in a world full of mostly cruel, self-centered, dishonest, and hateful people. It would be hell on earth. What strategies are there to try to develop a better character, and which of these strategies show substantial promise? In my book The Character Gap: How Good Are We?, I consider a number of different strategies. One I find quite interesting is what we might call “virtue labeling.” Suppose you come to believe, as I do, that most of the people we know do not have any of the virtues. So your friend, your boss, your neighbor … you need to change your opinion of all of them. Now here is the interesting idea—even with this new outlook firmly in mind, you should still go ahead and call them honest people next time you see them. You should still praise them for being compassionate. You should go out of your way to comment on their courage.

What strategies are there to try to develop a better character, and which of these strategies show substantial promise? In my book The Character Gap: How Good Are We?, I consider a number of different strategies. One I find quite interesting is what we might call “virtue labeling.” Suppose you come to believe, as I do, that most of the people we know do not have any of the virtues. So your friend, your boss, your neighbor … you need to change your opinion of all of them. Now here is the interesting idea—even with this new outlook firmly in mind, you should still go ahead and call them honest people next time you see them. You should still praise them for being compassionate. You should go out of your way to comment on their courage. You might feel that you have the ability to make choices, decisions and plans – and the freedom to change your mind at any point if you so desire – but many psychologists and scientists would tell you that this is an illusion. The denial of

You might feel that you have the ability to make choices, decisions and plans – and the freedom to change your mind at any point if you so desire – but many psychologists and scientists would tell you that this is an illusion. The denial of  Billions of years ago, life crossed a threshold. Single cells started to band together, and a world of formless, unicellular life was on course to evolve into the riot of shapes and functions of multicellular life today, from ants to pear trees to people. It’s a transition as momentous as any in the history of life, and until recently we had no idea how it happened.

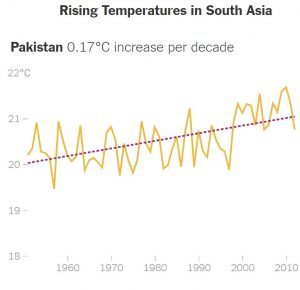

Billions of years ago, life crossed a threshold. Single cells started to band together, and a world of formless, unicellular life was on course to evolve into the riot of shapes and functions of multicellular life today, from ants to pear trees to people. It’s a transition as momentous as any in the history of life, and until recently we had no idea how it happened. Climate change could sharply diminish living conditions for up to 800 million people in South Asia, a region that is already home to some of the world’s poorest and hungriest people, if nothing is done to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions,

Climate change could sharply diminish living conditions for up to 800 million people in South Asia, a region that is already home to some of the world’s poorest and hungriest people, if nothing is done to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions, What did I do to deserve a yelling at from the famously curmudgeonly and irascible Harlan Ellison? Well, from 2010 to 2013, I was the president of SFWA, the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America, an organization to which Harlan belonged and which made him one of its Grand Masters in 2006. Harlan believed that as a Grand Master I was obliged to take his call whenever he felt like calling, which was usually late in the evening, as I was Eastern time and he was on Pacific time. So some time between 11 p.m. and 1 a.m., the phone would ring, and “It’s Harlan” would rumble across the wires, and then for the next 30 or so minutes, Harlan Ellison would expound on whatever it was he had a wart on his fanny about, which was sometimes about SFWA-related business, and sometimes just life in general.

What did I do to deserve a yelling at from the famously curmudgeonly and irascible Harlan Ellison? Well, from 2010 to 2013, I was the president of SFWA, the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America, an organization to which Harlan belonged and which made him one of its Grand Masters in 2006. Harlan believed that as a Grand Master I was obliged to take his call whenever he felt like calling, which was usually late in the evening, as I was Eastern time and he was on Pacific time. So some time between 11 p.m. and 1 a.m., the phone would ring, and “It’s Harlan” would rumble across the wires, and then for the next 30 or so minutes, Harlan Ellison would expound on whatever it was he had a wart on his fanny about, which was sometimes about SFWA-related business, and sometimes just life in general. F

F Moon Brow is a story of lust, love, and loss set during three periods of time: Iran’s revolution, the post-revolution and Eight Years War with Iraq, and the post-war era. An Eight Years War veteran, Amir Yamini, who formerly drowned himself in sex and alcohol, is discovered in a hospital for shell-shock victims by his mother and his sister Reyhaneh, having languished there for five years. Suffering from mental injuries caused by the war, Amir is haunted by a woman in his dreams that he calls “Moon Brow” because he can’t see her face. Amir’s attempt to seek the truth of his past brings him to his old friend, Kaveh, who might know what happened in Amir’s past life. The search for a woman he truly loved before going to war takes him to where he lost his left arm—and his wedding ring—during the war. Amir’s relationship with his sister Reyhaneh is one of the best parts of the novel—a true companion, Reyhaneh helps Amir discover the truth of his life before the war. Moon Brow combines Amir’s journey into his past life with the history of Iran, and also it shares the trauma of war as it reveals the victims of Saddam Hussein’s genocidal ideology.

Moon Brow is a story of lust, love, and loss set during three periods of time: Iran’s revolution, the post-revolution and Eight Years War with Iraq, and the post-war era. An Eight Years War veteran, Amir Yamini, who formerly drowned himself in sex and alcohol, is discovered in a hospital for shell-shock victims by his mother and his sister Reyhaneh, having languished there for five years. Suffering from mental injuries caused by the war, Amir is haunted by a woman in his dreams that he calls “Moon Brow” because he can’t see her face. Amir’s attempt to seek the truth of his past brings him to his old friend, Kaveh, who might know what happened in Amir’s past life. The search for a woman he truly loved before going to war takes him to where he lost his left arm—and his wedding ring—during the war. Amir’s relationship with his sister Reyhaneh is one of the best parts of the novel—a true companion, Reyhaneh helps Amir discover the truth of his life before the war. Moon Brow combines Amir’s journey into his past life with the history of Iran, and also it shares the trauma of war as it reveals the victims of Saddam Hussein’s genocidal ideology. I’m asking myself about double standards a lot lately, in public life and also in science. I’m particularly concerned about double standards in science whereby women’s issues are viewed differently than men’s. We’ve lagged behind in important ways because there is a concern that if we have a biological explanation for women’s behavior, it will smash women up against the glass ceiling, whereas a biological explanation for men’s behavior doesn’t do such a thing. So, we’ve been freer in biomedical science to explore questions about the biological foundations of men’s behavior and less free to explore those questions about women’s behavior. That’s a problem that manifests itself in the lag behind what we understand about men and what we understand about women.

I’m asking myself about double standards a lot lately, in public life and also in science. I’m particularly concerned about double standards in science whereby women’s issues are viewed differently than men’s. We’ve lagged behind in important ways because there is a concern that if we have a biological explanation for women’s behavior, it will smash women up against the glass ceiling, whereas a biological explanation for men’s behavior doesn’t do such a thing. So, we’ve been freer in biomedical science to explore questions about the biological foundations of men’s behavior and less free to explore those questions about women’s behavior. That’s a problem that manifests itself in the lag behind what we understand about men and what we understand about women. In the 1970s, Shulamith Firestone

In the 1970s, Shulamith Firestone  In his 1946 classic essay ‘Politics and the English language’, George Orwell argued that “if thought corrupts language, language can also corrupt thought”. Can the same be said for science — that the misuse and misapplication of language could corrupt research? Two neuroscientists believe that it can. In an intriguing paper published in the Journal of Neurogenetics, the duo claims that muddled phrasing in biology leads to muddled thought and, worse, flawed conclusions.

In his 1946 classic essay ‘Politics and the English language’, George Orwell argued that “if thought corrupts language, language can also corrupt thought”. Can the same be said for science — that the misuse and misapplication of language could corrupt research? Two neuroscientists believe that it can. In an intriguing paper published in the Journal of Neurogenetics, the duo claims that muddled phrasing in biology leads to muddled thought and, worse, flawed conclusions. THIRTY YEARS AGO, while the Midwest withered in massive drought and East Coast temperatures exceeded 100 degrees Fahrenheit, I testified to the Senate as a senior NASA scientist about climate change. I said that ongoing global warming was outside the range of natural variability and it could be attributed, with high confidence, to human activity — mainly from the spewing of carbon dioxide and other heat-trapping gases into the atmosphere. “It’s time to stop waffling so much and say that the evidence is pretty strong that the greenhouse effect is here,” I said.

THIRTY YEARS AGO, while the Midwest withered in massive drought and East Coast temperatures exceeded 100 degrees Fahrenheit, I testified to the Senate as a senior NASA scientist about climate change. I said that ongoing global warming was outside the range of natural variability and it could be attributed, with high confidence, to human activity — mainly from the spewing of carbon dioxide and other heat-trapping gases into the atmosphere. “It’s time to stop waffling so much and say that the evidence is pretty strong that the greenhouse effect is here,” I said. By several measures, including rates of poverty and violence, progress is an international reality. Why, then, do so many of us believe otherwise?

By several measures, including rates of poverty and violence, progress is an international reality. Why, then, do so many of us believe otherwise? If the names of these Black Oberlinites are unfamiliar, I suspect it is with good reason: we do not know how to talk about them. Over the course of my life I have learned that to be black and a classical musician is to be considered a contradiction. After hearing that I was a music major, a TSA agent asked me if I was studying jazz. One summer in Bayreuth, a white German businessman asked me what I was doing in his town. Upon hearing that I was researching the history of Wagner’s opera house, he remarked, “But you look like you’re from Africa.” After I gushed about Mahler’s Fifth Symphony, someone once told me that I wasn’t “really black.” All too often, black artistic activities can only be recognized in “black” arts.

If the names of these Black Oberlinites are unfamiliar, I suspect it is with good reason: we do not know how to talk about them. Over the course of my life I have learned that to be black and a classical musician is to be considered a contradiction. After hearing that I was a music major, a TSA agent asked me if I was studying jazz. One summer in Bayreuth, a white German businessman asked me what I was doing in his town. Upon hearing that I was researching the history of Wagner’s opera house, he remarked, “But you look like you’re from Africa.” After I gushed about Mahler’s Fifth Symphony, someone once told me that I wasn’t “really black.” All too often, black artistic activities can only be recognized in “black” arts. Last week, the philosopher Stanley Cavell died. His contributions to human thought are vast and rich; his subjects range from the intricacies of human language to the nature of skill. But one of Cavell’s best-known books is also, at least at first glance, his most frivolous: Pursuits of Happiness. In this book, originally published in 1981, Cavell claims that what he calls “comedies of remarriage”—Hollywood comedies from the 1930s and 40s that share a set of genre conventions (borderline farcical cons, absent mothers, weaponized erotic dialogue), actors (Cary Grant, Clark Gable, Katharine Hepburn, Barbara Stanwyck), and settings (Connecticut)—are the inheritors of the tradition of Shakespearean comedy and romance, and that they constitute a philosophically significant body of work.

Last week, the philosopher Stanley Cavell died. His contributions to human thought are vast and rich; his subjects range from the intricacies of human language to the nature of skill. But one of Cavell’s best-known books is also, at least at first glance, his most frivolous: Pursuits of Happiness. In this book, originally published in 1981, Cavell claims that what he calls “comedies of remarriage”—Hollywood comedies from the 1930s and 40s that share a set of genre conventions (borderline farcical cons, absent mothers, weaponized erotic dialogue), actors (Cary Grant, Clark Gable, Katharine Hepburn, Barbara Stanwyck), and settings (Connecticut)—are the inheritors of the tradition of Shakespearean comedy and romance, and that they constitute a philosophically significant body of work.