Sarah Perry in the London Review of Books:

In the small hours of a spring morning last year I asked for a hot-water bottle to be put on my calf: a ruptured disc was crushing my sciatic nerve, causing leg pain unappeased by opioids and benzodiazepines. I went back to sleep. When I woke up, I felt a damp substance on my leg, and when I wiped it off, I noticed a wet white rag was hanging from my fingertips. I thought little of it: pain was my sole preoccupation at the time, and there wasn’t any. Later that day, awaiting surgery, I was told the hot-water bottle had caused a burn clean through the epidermis, cauterising the nerves.

In the small hours of a spring morning last year I asked for a hot-water bottle to be put on my calf: a ruptured disc was crushing my sciatic nerve, causing leg pain unappeased by opioids and benzodiazepines. I went back to sleep. When I woke up, I felt a damp substance on my leg, and when I wiped it off, I noticed a wet white rag was hanging from my fingertips. I thought little of it: pain was my sole preoccupation at the time, and there wasn’t any. Later that day, awaiting surgery, I was told the hot-water bottle had caused a burn clean through the epidermis, cauterising the nerves.

The burn became a black disc so tough you could rap it like the cover of a leather-bound book; I fretted about scarring, but what concerned the doctors was the possibility of my acquiring one of the antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria that plague hospital wards. Two weeks later – the necrotic flesh had receded to reveal body fat resembling butter softened in the microwave – a GP peeled the dressing off, lifted it to her nose, and recoiled at the unmistakeable smell of infection. Swabs were taken, but it was merely the Staphylococcus aureus bacterium, its name deriving from the Greek for ‘grape-cluster berry’, which it resembles. A course of antibiotics, frequent sluicings with saline, and all would be well.

In the days of Lister, Liston and Pasteur, such infections were thought to be an example of what was known as ‘hospitalism’, for the better prevention of which it was even proposed that all hospitals should be razed by fire and rebuilt every ten years or so.

More here.

As many critics have noted, Hill established himself from the beginning as an elegist. The title For the Unfallen promises a

memorial for the living, and the book itself contains “

As many critics have noted, Hill established himself from the beginning as an elegist. The title For the Unfallen promises a

memorial for the living, and the book itself contains “ Laura Ingalls Wilder

Laura Ingalls Wilder Like many women, Baskin was buying things that male dealers weren’t interested in, such as women printers and artists, which put her under the radar. “In the sixties, I could be a ferret and find things,” she said, citing a late 17th century-early 18th century book by Maria Sibylla Merian, the first person of either gender to observe and draw the metamorphoses of insects in the field. “She made some of the most beautiful books,” Baskin said. “As a child, Merian was fascinated by watching caterpillars turn into moths. She made a book about the insects of Suriname and another about the insects of Europe.” Baskin purchased a copy of Merian’s De Europische Insecten (1730); copies of the book about the insects of Suriname go for hundreds of thousands of dollars now. “The issue is: Are women taken seriously as dealers and as collectors? I don’t think it’s a reflection on the works they sell or collect. I think these works were, and are, valued less,” says Baskin. She mentions J.P. Morgan’s (d. 1913) great Morgan Library, whose collection—of books by both men and women—was largely acquired by its director and librarian Belle da Costa Greene, daughter of the first African American to graduate from Harvard. “It was said that da Costa Greene had the brains and the wit and Morgan had the money,” Baskin says.

Like many women, Baskin was buying things that male dealers weren’t interested in, such as women printers and artists, which put her under the radar. “In the sixties, I could be a ferret and find things,” she said, citing a late 17th century-early 18th century book by Maria Sibylla Merian, the first person of either gender to observe and draw the metamorphoses of insects in the field. “She made some of the most beautiful books,” Baskin said. “As a child, Merian was fascinated by watching caterpillars turn into moths. She made a book about the insects of Suriname and another about the insects of Europe.” Baskin purchased a copy of Merian’s De Europische Insecten (1730); copies of the book about the insects of Suriname go for hundreds of thousands of dollars now. “The issue is: Are women taken seriously as dealers and as collectors? I don’t think it’s a reflection on the works they sell or collect. I think these works were, and are, valued less,” says Baskin. She mentions J.P. Morgan’s (d. 1913) great Morgan Library, whose collection—of books by both men and women—was largely acquired by its director and librarian Belle da Costa Greene, daughter of the first African American to graduate from Harvard. “It was said that da Costa Greene had the brains and the wit and Morgan had the money,” Baskin says. Our planet is in a perilous state. The combined effects of climate change, pollution, and loss of biodiversity are putting our health and well-being at risk. Given that human actions are largely responsible for these global problems, humanity must now nudge Earth onto a trajectory toward a more stable, harmonious state. Many of the challenges are daunting, but solutions can be found. In this issue of Science, we launch a series of monthly articles that call attention to some of the choices we can still make for shaping tomorrow’s Earth—commentaries and analyses that will hopefully provoke us to making thoughtful choices (see

Our planet is in a perilous state. The combined effects of climate change, pollution, and loss of biodiversity are putting our health and well-being at risk. Given that human actions are largely responsible for these global problems, humanity must now nudge Earth onto a trajectory toward a more stable, harmonious state. Many of the challenges are daunting, but solutions can be found. In this issue of Science, we launch a series of monthly articles that call attention to some of the choices we can still make for shaping tomorrow’s Earth—commentaries and analyses that will hopefully provoke us to making thoughtful choices (see  If you grew up in South Asia, the lush 17th-century romance of a captivating young widow and a Moghul emperor is likely as familiar to you as Romeo & Juliet are in the West. They meet, and she wows the ruler of tens of millions of people with her beauty, wit, and fearlessness. Wise and savvy, she becomes his beloved 20th wife and goes on to live an extraordinary life. She writes poetry, designs gardens and buildings, and even saves a village by hunting down and killing four dangerous tigers with six shots. That’s as far as the legend and the history books tend to go. But there’s much more to the story, as historian Ruby Lal reveals in her fascinating new book Empress: The Astonishing Reign of Nur Jahan.

If you grew up in South Asia, the lush 17th-century romance of a captivating young widow and a Moghul emperor is likely as familiar to you as Romeo & Juliet are in the West. They meet, and she wows the ruler of tens of millions of people with her beauty, wit, and fearlessness. Wise and savvy, she becomes his beloved 20th wife and goes on to live an extraordinary life. She writes poetry, designs gardens and buildings, and even saves a village by hunting down and killing four dangerous tigers with six shots. That’s as far as the legend and the history books tend to go. But there’s much more to the story, as historian Ruby Lal reveals in her fascinating new book Empress: The Astonishing Reign of Nur Jahan. Inasmuch as he had a specialization, Cavell’s was our human life in words and he, along with Cora Diamond and James Conant, is credited with giving second life to a hitherto expiring mode of thought known as ordinary language philosophy. Cavell was fascinated by how language proves constitutive of what it means to be human, and was further fascinated by how much we humans want to deny that—probably, he thought, because of what the implications would demand of us. In a characteristically exquisite passage from the legendary fourth part of The Claim of Reason, Cavell wrote, “There is no assignable end to the depth of us to which language reaches; that nevertheless there is no end to our separateness. We are endlessly separate, for no reason. But then we are answerable for everything that comes between us; if not for causing it then for continuing it; if not for denying it then for affirming it; if not for it then to it.”

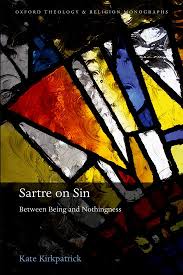

Inasmuch as he had a specialization, Cavell’s was our human life in words and he, along with Cora Diamond and James Conant, is credited with giving second life to a hitherto expiring mode of thought known as ordinary language philosophy. Cavell was fascinated by how language proves constitutive of what it means to be human, and was further fascinated by how much we humans want to deny that—probably, he thought, because of what the implications would demand of us. In a characteristically exquisite passage from the legendary fourth part of The Claim of Reason, Cavell wrote, “There is no assignable end to the depth of us to which language reaches; that nevertheless there is no end to our separateness. We are endlessly separate, for no reason. But then we are answerable for everything that comes between us; if not for causing it then for continuing it; if not for denying it then for affirming it; if not for it then to it.” Kate Kirkpatrick’s provocative interdisciplinary study argues that Sartre’s conception of nothingness in Being and Nothingness (BN) can be fruitfully understood as an iteration of the Christian doctrine of original sin, “nothingness” being synonymous with sin and evil in the Augustinian tradition. Hence, Sartre in BN presents us with “a phenomenology of sin from a graceless position” (10). For readers used to understanding Sartre through the lens of German phenomenology, this will come as a surprise. However, the book should be welcomed by all readers as it breathes life into the field of Sartre studies, offering a fresh perspective from which to judge the magnum opus of French existentialism.

Kate Kirkpatrick’s provocative interdisciplinary study argues that Sartre’s conception of nothingness in Being and Nothingness (BN) can be fruitfully understood as an iteration of the Christian doctrine of original sin, “nothingness” being synonymous with sin and evil in the Augustinian tradition. Hence, Sartre in BN presents us with “a phenomenology of sin from a graceless position” (10). For readers used to understanding Sartre through the lens of German phenomenology, this will come as a surprise. However, the book should be welcomed by all readers as it breathes life into the field of Sartre studies, offering a fresh perspective from which to judge the magnum opus of French existentialism. W

W As we commence celebrating July 4th with the time-honored traditions of beer, block parties and cookouts, it’s fun to imagine a cookout where the Founding Fathers gathered around a grill discussing the details of the Declaration of Independence. Did George Washington prefer dogs or burgers? Was Benjamin Franklin a ketchup or mustard guy? And why did they all avoid drinking water?

As we commence celebrating July 4th with the time-honored traditions of beer, block parties and cookouts, it’s fun to imagine a cookout where the Founding Fathers gathered around a grill discussing the details of the Declaration of Independence. Did George Washington prefer dogs or burgers? Was Benjamin Franklin a ketchup or mustard guy? And why did they all avoid drinking water? A striking show of sculpture from 14th century Europe to the present,

A striking show of sculpture from 14th century Europe to the present,  I WAS TOLD by Stephan Harding that “if there was the slightest chance of a cold, we will have to cancel. He had bronchitis not long ago; we can’t afford to take any risks.” But, despite the Arctic cold that had descended on England in February, I wasn’t coughing or anything, so we decided to embark. Nevertheless, we took the precaution of washing our hands carefully with antiseptic soap a few times. And then we were off for the coast of Dorset, in the south of England, in the direction of Cornwall.

I WAS TOLD by Stephan Harding that “if there was the slightest chance of a cold, we will have to cancel. He had bronchitis not long ago; we can’t afford to take any risks.” But, despite the Arctic cold that had descended on England in February, I wasn’t coughing or anything, so we decided to embark. Nevertheless, we took the precaution of washing our hands carefully with antiseptic soap a few times. And then we were off for the coast of Dorset, in the south of England, in the direction of Cornwall. One summer night, when I was a child, my mother and I were scouring the night sky for stars, meteors, and planets.

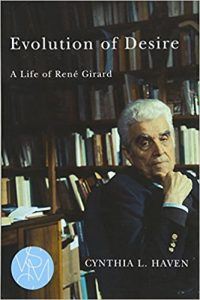

One summer night, when I was a child, my mother and I were scouring the night sky for stars, meteors, and planets. Cynthia L. Haven’s “Evolution of Desire: A Life of René Girard” is the first full-length biography of the acclaimed French thinker. Girard’s “mimetic theory” saw imitation at the heart of individual desire and motivation, accounting for the competition and violence that galvanize cultures and societies. “Girard claimed that mimetic desire is not only the way we love, it’s the reason we fight. Two hands that reach towards the same object will ultimately clench into fists.”

Cynthia L. Haven’s “Evolution of Desire: A Life of René Girard” is the first full-length biography of the acclaimed French thinker. Girard’s “mimetic theory” saw imitation at the heart of individual desire and motivation, accounting for the competition and violence that galvanize cultures and societies. “Girard claimed that mimetic desire is not only the way we love, it’s the reason we fight. Two hands that reach towards the same object will ultimately clench into fists.” At a book reading in Kolkata, about a week after my first novel,

At a book reading in Kolkata, about a week after my first novel,  Born to an Ashkenazi Jewish father and mother of Irish and German descent, science and heredity has long fascinated Carl Zimmer.

Born to an Ashkenazi Jewish father and mother of Irish and German descent, science and heredity has long fascinated Carl Zimmer.