by Thomas Wells

Middle age brings sometimes uncomfortable self-reflection. One thing I have realized is that I am not a particularly good person. Not evil, just mediocre. Lots of people are much better at morality than me, including many of my students. On the other hand, I am quite good at the academic subject of ethics. Good enough to teach it at a university and write papers that occasionally appear in nice journals.

Middle age brings sometimes uncomfortable self-reflection. One thing I have realized is that I am not a particularly good person. Not evil, just mediocre. Lots of people are much better at morality than me, including many of my students. On the other hand, I am quite good at the academic subject of ethics. Good enough to teach it at a university and write papers that occasionally appear in nice journals.

Is there a contradiction between these two observations? Is there a causal relationship?

When I started studying ethics I assumed it would somehow make me a morally better person. But I never really thought through that ‘somehow’ and after 15 years I can see that my complacency was not justified. My moral achievements still derive mostly from the good habits my parents trained me in. If I am at all a better person than I was 15 years ago, that has had more to do with the good people I have been lucky enough to know than with what I have been reading, thinking, and teaching.

Some years ago, for instance, I worked through the arguments around animal rights and decided to my intellectual satisfaction that the case against eating them was completely compelling. But I still eat meat nearly every day. I did try vegetarianism a couple of times but gave up because it was too hard. Vegetarian food in every situation was always worse than the meat alternative. And I got very tired of eating cheese.

Aristotle would diagnose my failing as akrasia, or weakness of will. I characterize it in more familiar terms as moral laziness. I claim moral principles, but I am not prepared to put much effort into living up to them. In the same way, I think I want to be thin, but – practice has revealed – I am not prepared to exchange my comforts for ascetic bowls of muesli and pre-dawn running regimes. Either I don’t care about being good as much as I think I do (a motivation problem), or I am not really convinced by my own moral reasoning (a rationality problem). I think it may be a bit of both. Read more »

How conceivable is this? Trump loses the 2020 US presidential election. But he refuses to concede, claiming that results in the swing states of Ohio and Florida were invalid due to voter fraud and crooked election officials. Fox News, other right-wing media and the Republican controlled congress go along with this. So Trump remains president until, in the words of Senate leader Mitch McConnell, “we are able to clear up this mess.” Clearing up the mess, it turns out, could take some time–even longer than it takes for Trump to fulfill his promise to release his tax returns. Law suits are brought, but guess what? By a 5 to 4 majority, the supreme court refuses to hear them.

How conceivable is this? Trump loses the 2020 US presidential election. But he refuses to concede, claiming that results in the swing states of Ohio and Florida were invalid due to voter fraud and crooked election officials. Fox News, other right-wing media and the Republican controlled congress go along with this. So Trump remains president until, in the words of Senate leader Mitch McConnell, “we are able to clear up this mess.” Clearing up the mess, it turns out, could take some time–even longer than it takes for Trump to fulfill his promise to release his tax returns. Law suits are brought, but guess what? By a 5 to 4 majority, the supreme court refuses to hear them.

What unites Mark Zuckerberg and the Koch Brothers? For many, their politics appear to set them apart. At least before the Cambridge Analytica revelations of last spring, Zuckerberg seemed the darling of a certain kind of liberal, announcing on Oprah Winfrey’s television show that he planned to spend $100 million to fix the Newark school system, declaring (in a talk at the University of California, San Francisco) that he plans to use his limited-liability philanthropic corporation to “cure, prevent or manage all diseases,” promising to use his vast riches to help create “a future for everyone,” as the promotional materials for the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative put it—all of which led his name to be batted about as a possible Democratic presidential candidate in 2020. The oil magnate Kochs, on the other hand—leading supporters of libertarian political organizations like Americans for Prosperity—have become synonymous with “dark money” efforts by elusive billionaires to push right-wing politics.

What unites Mark Zuckerberg and the Koch Brothers? For many, their politics appear to set them apart. At least before the Cambridge Analytica revelations of last spring, Zuckerberg seemed the darling of a certain kind of liberal, announcing on Oprah Winfrey’s television show that he planned to spend $100 million to fix the Newark school system, declaring (in a talk at the University of California, San Francisco) that he plans to use his limited-liability philanthropic corporation to “cure, prevent or manage all diseases,” promising to use his vast riches to help create “a future for everyone,” as the promotional materials for the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative put it—all of which led his name to be batted about as a possible Democratic presidential candidate in 2020. The oil magnate Kochs, on the other hand—leading supporters of libertarian political organizations like Americans for Prosperity—have become synonymous with “dark money” efforts by elusive billionaires to push right-wing politics. J.M. Coetzee: Balzac famously wrote that behind every great fortune lies a crime. One might similarly claim that behind every successful colonial venture lies a crime, a crime of dispossession. Just as in the dynastic novels of the nineteenth century the heirs of great fortunes are haunted by the crimes on which their fortunes were founded, a successful colony like Australia seems to be haunted by a history that will not go away. The question of what to say or do about dispossession of Indigenous Australians is as alive in the Australian imagination as it has ever been.

J.M. Coetzee: Balzac famously wrote that behind every great fortune lies a crime. One might similarly claim that behind every successful colonial venture lies a crime, a crime of dispossession. Just as in the dynastic novels of the nineteenth century the heirs of great fortunes are haunted by the crimes on which their fortunes were founded, a successful colony like Australia seems to be haunted by a history that will not go away. The question of what to say or do about dispossession of Indigenous Australians is as alive in the Australian imagination as it has ever been. The modern separation among scholars between intellectual history and the history of mathematics is untenable as mathematics might be the ultimate intellectual endeavour. In the words of the 19th-century German mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss: ‘mathematics is the queen of the sciences’; like literacy, widespread numeracy is one of the defining features of modernity. In fact, one of the great shifts of modernity has been how mathematicians changed their view of mathematics, transforming the focus of their work from the study of the natural world to the study of ideas and concepts. Perhaps more than any other subject, mathematics is about the study of ideas. Yet, when people invoke the history of ideas, you are unlikely to hear about Dedekind’s cut (that is, the technique by which the real numbers are rigorously defined from the rational numbers), or L E J Brouwer’s rejection of Aristotle’s ‘law of excluded middle’, which states that any proposition is either true or that its negation is (put technically: for all propositions p, either p or not p). Nor are you likely to hear about the contested history of these ideas. Generally, when they talk about ideas, intellectual historians today mean political thought, cultural analysis, and maybe a sprinkling of economic and religious concepts, too.

The modern separation among scholars between intellectual history and the history of mathematics is untenable as mathematics might be the ultimate intellectual endeavour. In the words of the 19th-century German mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss: ‘mathematics is the queen of the sciences’; like literacy, widespread numeracy is one of the defining features of modernity. In fact, one of the great shifts of modernity has been how mathematicians changed their view of mathematics, transforming the focus of their work from the study of the natural world to the study of ideas and concepts. Perhaps more than any other subject, mathematics is about the study of ideas. Yet, when people invoke the history of ideas, you are unlikely to hear about Dedekind’s cut (that is, the technique by which the real numbers are rigorously defined from the rational numbers), or L E J Brouwer’s rejection of Aristotle’s ‘law of excluded middle’, which states that any proposition is either true or that its negation is (put technically: for all propositions p, either p or not p). Nor are you likely to hear about the contested history of these ideas. Generally, when they talk about ideas, intellectual historians today mean political thought, cultural analysis, and maybe a sprinkling of economic and religious concepts, too.

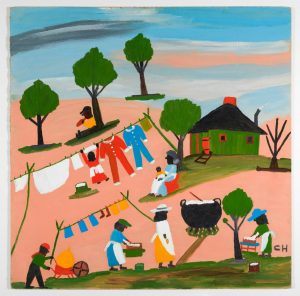

She was born just 20 years after the Civil War. Her grandparents were enslaved. And after decades of working in a storied Louisiana plantation, Clementine Hunter picked up a brush and began depicting African-American life in the South, turning out thousands of paintings first sold for less than a dollar that are now fetching thousands. Often called the black Grandma Moses, for the simplicity of her work and her late life enthusiasm for it, the artist, who died in 1988 at age 101, is being celebrated in an exhibition held in the Rhimes Family Foundation Visual Art Gallery at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.

She was born just 20 years after the Civil War. Her grandparents were enslaved. And after decades of working in a storied Louisiana plantation, Clementine Hunter picked up a brush and began depicting African-American life in the South, turning out thousands of paintings first sold for less than a dollar that are now fetching thousands. Often called the black Grandma Moses, for the simplicity of her work and her late life enthusiasm for it, the artist, who died in 1988 at age 101, is being celebrated in an exhibition held in the Rhimes Family Foundation Visual Art Gallery at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. Nine pints, give or take. That’s how much blood you have, surging in time to “the old brag”, as Sylvia Plath put it, of your heart. Although for

Nine pints, give or take. That’s how much blood you have, surging in time to “the old brag”, as Sylvia Plath put it, of your heart. Although for  Paul Allen, one of my oldest friends and the first business partner I ever had, died yesterday. I want to extend my condolences to his sister, Jody, his extended family, and his many friends and colleagues around the world.

Paul Allen, one of my oldest friends and the first business partner I ever had, died yesterday. I want to extend my condolences to his sister, Jody, his extended family, and his many friends and colleagues around the world. Imprisoned in the fortress of Taureau, a tiny thumb of rock off the windswept coast of Brittany, the French revolutionary Louis-Auguste Blanqui gazed toward the stars. He had been locked up for his role in the socialist movement that would lead to the Paris Commune of 1871. As Blanqui looked up at the night sky, he found comfort in the possibility of other worlds. While life on Earth is fleeting, he wrote in Eternity by the Stars(1872), we might take solace in the notion that myriad replicas of our planet are brimming with similar creatures – that all events, he said, ‘that have taken place or that are yet to take place on our globe, before it dies, take place in exactly the same way on its billions of duplicates’. Might certain souls be imprisoned on these faraway worlds, too? Perhaps. But Blanqui held out hope that, through chance mutations, those who are unjustly jailed down here on Earth might there walk free.

Imprisoned in the fortress of Taureau, a tiny thumb of rock off the windswept coast of Brittany, the French revolutionary Louis-Auguste Blanqui gazed toward the stars. He had been locked up for his role in the socialist movement that would lead to the Paris Commune of 1871. As Blanqui looked up at the night sky, he found comfort in the possibility of other worlds. While life on Earth is fleeting, he wrote in Eternity by the Stars(1872), we might take solace in the notion that myriad replicas of our planet are brimming with similar creatures – that all events, he said, ‘that have taken place or that are yet to take place on our globe, before it dies, take place in exactly the same way on its billions of duplicates’. Might certain souls be imprisoned on these faraway worlds, too? Perhaps. But Blanqui held out hope that, through chance mutations, those who are unjustly jailed down here on Earth might there walk free. I READ DENNIS COOPER for the first time when I was a 23-year-old student in an MFA program. No professor assigned him to me. Cooper’s language is blunt, often sounding as though spoken through a veil of intoxicants, and his tales of insecure gay teenagers and the men who castrate, murder, disembowel, and cannibalize them would have been a hard pitch to those who had come to grad school to learn how to sell their manuscripts. The only other openly gay student in my writing cohort, K., recommended the George Miles Cycle (1989–2000) and God Jr. (2005), his voice catching as we talked. He was afraid to read The Sluts (2004), because he had recently been through a breakup and he was concerned that a narrative about a group of middle-aged men who become obsessed with a prostitute named Brad, using internet chat rooms to describe his torture and death, might mar his sense of the possibilities of single life as a sexually active gay person.

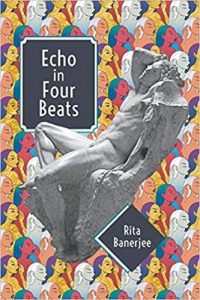

I READ DENNIS COOPER for the first time when I was a 23-year-old student in an MFA program. No professor assigned him to me. Cooper’s language is blunt, often sounding as though spoken through a veil of intoxicants, and his tales of insecure gay teenagers and the men who castrate, murder, disembowel, and cannibalize them would have been a hard pitch to those who had come to grad school to learn how to sell their manuscripts. The only other openly gay student in my writing cohort, K., recommended the George Miles Cycle (1989–2000) and God Jr. (2005), his voice catching as we talked. He was afraid to read The Sluts (2004), because he had recently been through a breakup and he was concerned that a narrative about a group of middle-aged men who become obsessed with a prostitute named Brad, using internet chat rooms to describe his torture and death, might mar his sense of the possibilities of single life as a sexually active gay person. Whilst Banerjee recognises the beauty and utility of traditional forms, she plays with a multitude of poetic and thematic forms, pirouetting from the profane to the sacred, the mundane to the sublime, the broadly public to the deeply profound and personal with the ease of a virtuoso. Haiku is placed alongside sonnets and ghazals, interspersed with erasure, hymns, mistranslations and vers-libre to give birth to different metronomic languages and rhythms that create a new voice. Banerjee´s linguistic artfulness resides in her ability to translate all these foreign words, cultures, and geographies into a coherent language of aesthetic, philosophical, and political portent. As seen in the haiku “A Waters Sound” where the entrenchment of social conventions and power structures is metaphorically conveyed by the image of a deep, leaf-grown well from which potential young feminists are blocked from jumping out by the wire-meshed sky. The Japanese ideograms of the original poem drip silently down the face of the page, creating and holding a meditative space for the reader to ruminate upon the depth of the well.

Whilst Banerjee recognises the beauty and utility of traditional forms, she plays with a multitude of poetic and thematic forms, pirouetting from the profane to the sacred, the mundane to the sublime, the broadly public to the deeply profound and personal with the ease of a virtuoso. Haiku is placed alongside sonnets and ghazals, interspersed with erasure, hymns, mistranslations and vers-libre to give birth to different metronomic languages and rhythms that create a new voice. Banerjee´s linguistic artfulness resides in her ability to translate all these foreign words, cultures, and geographies into a coherent language of aesthetic, philosophical, and political portent. As seen in the haiku “A Waters Sound” where the entrenchment of social conventions and power structures is metaphorically conveyed by the image of a deep, leaf-grown well from which potential young feminists are blocked from jumping out by the wire-meshed sky. The Japanese ideograms of the original poem drip silently down the face of the page, creating and holding a meditative space for the reader to ruminate upon the depth of the well. The street between Nora’s hotel and Oscar Wilde’s house is called Clare Street. Beckett’s father ran his quantity surveying business from No 6 but there is no plaque here. When their father died in 1933, Beckett’s brother took over the business while Beckett, who was idling at the time, took the attic room. Like all idlers, he made many promises; in this case, both to himself and to his mother. He promised himself that he would write and he promised his mother that he would give language lessons. But he did nothing much. It would look good on a plaque: “This is where Samuel Beckett did nothing much.”

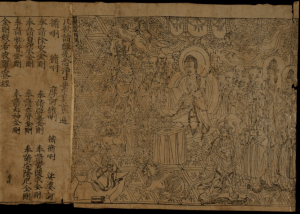

The street between Nora’s hotel and Oscar Wilde’s house is called Clare Street. Beckett’s father ran his quantity surveying business from No 6 but there is no plaque here. When their father died in 1933, Beckett’s brother took over the business while Beckett, who was idling at the time, took the attic room. Like all idlers, he made many promises; in this case, both to himself and to his mother. He promised himself that he would write and he promised his mother that he would give language lessons. But he did nothing much. It would look good on a plaque: “This is where Samuel Beckett did nothing much.” The Library Cave was bricked up some time in the 11th century, for unknown reasons: perhaps to keep the books safe from invaders; or perhaps, given the large number of worn and partial texts, the chamber was less a library than a tomb for books. Locals continued to worship at the shrines, but several of the the exterior walkways connecting the ancient cave entrances collapsed, and the sand that slowly filled many of the caves severely abraded their delicate murals.

The Library Cave was bricked up some time in the 11th century, for unknown reasons: perhaps to keep the books safe from invaders; or perhaps, given the large number of worn and partial texts, the chamber was less a library than a tomb for books. Locals continued to worship at the shrines, but several of the the exterior walkways connecting the ancient cave entrances collapsed, and the sand that slowly filled many of the caves severely abraded their delicate murals.