Rowan Williams at Literary Review:

In a late poem about a friend’s death, Czesław Miłosz writes of the long passage between youth and age as one of learning ‘how to bear what is borne by others’. It could be a summary of his own poetic witness. Eva Hoffman’s moving and eloquent essay traces the ways in which that simultaneously guilty, compassionate and fastidious response characterises Miłosz’s work from its earliest days. Bearing what is borne by others is, for Miłosz, close to the heart of the poetic task, but it is also fraught with risk. Hoffman pinpoints how Miłosz’s hypersensitivity to the risks of sentimentality and grandstanding led to what many readers saw as an evasion of necessary commitment. He stood aside during the Warsaw Rising of 1944, wary of the overheated and unrealistic rhetoric surrounding it; he saw his first duty as being to the integrity of his poetry, not to the mythology of a sacrificially heroic Poland. Yet, as Hoffman stresses, the poetry itself reveals his full awareness of ambivalent motives and the dangers of willed detachment. Was he nervous of ‘being overwhelmed by emotions from which no detachment was possible’? The lines (from 1945), ‘You swore never to touch/The deep wounds of your nation’ – indeed, the whole poem in which they occur – reveal both a concern not to cheapen such wounds by sacralising the agonies of others and a recognition of the unbearable character of the pain involved: ‘My pen is lighter/Than a hummingbird’s feather. This burden/Is too much for it to bear.’

In a late poem about a friend’s death, Czesław Miłosz writes of the long passage between youth and age as one of learning ‘how to bear what is borne by others’. It could be a summary of his own poetic witness. Eva Hoffman’s moving and eloquent essay traces the ways in which that simultaneously guilty, compassionate and fastidious response characterises Miłosz’s work from its earliest days. Bearing what is borne by others is, for Miłosz, close to the heart of the poetic task, but it is also fraught with risk. Hoffman pinpoints how Miłosz’s hypersensitivity to the risks of sentimentality and grandstanding led to what many readers saw as an evasion of necessary commitment. He stood aside during the Warsaw Rising of 1944, wary of the overheated and unrealistic rhetoric surrounding it; he saw his first duty as being to the integrity of his poetry, not to the mythology of a sacrificially heroic Poland. Yet, as Hoffman stresses, the poetry itself reveals his full awareness of ambivalent motives and the dangers of willed detachment. Was he nervous of ‘being overwhelmed by emotions from which no detachment was possible’? The lines (from 1945), ‘You swore never to touch/The deep wounds of your nation’ – indeed, the whole poem in which they occur – reveal both a concern not to cheapen such wounds by sacralising the agonies of others and a recognition of the unbearable character of the pain involved: ‘My pen is lighter/Than a hummingbird’s feather. This burden/Is too much for it to bear.’

more here.

Willa Cather loathed biographers, professors, and autograph fiends. After her war novel, One of Ours, won the Pulitzer in 1923, she decided to cull the herd. “This is not a case for the Federal Bureau of Investigation,” she told one researcher. Burn my letters and manuscripts, she begged her friends. Hollywood filmed a loose adaptation of A Lost Lady, starring Barbara Stanwyck, in 1934, and Cather soon forbade any further screen, radio, and television versions of her work. No direct quotations from surviving correspondence, she ordered libraries, and for decades a family trust enforced her commands.

Willa Cather loathed biographers, professors, and autograph fiends. After her war novel, One of Ours, won the Pulitzer in 1923, she decided to cull the herd. “This is not a case for the Federal Bureau of Investigation,” she told one researcher. Burn my letters and manuscripts, she begged her friends. Hollywood filmed a loose adaptation of A Lost Lady, starring Barbara Stanwyck, in 1934, and Cather soon forbade any further screen, radio, and television versions of her work. No direct quotations from surviving correspondence, she ordered libraries, and for decades a family trust enforced her commands. In 2015, while working as an undergraduate researcher at the North Carolina Zoo, Laura Lewis became friends with a male chimpanzee named Kendall. Whenever she visited the chimps, Kendall would gently take her hands and inspect her fingernails.

In 2015, while working as an undergraduate researcher at the North Carolina Zoo, Laura Lewis became friends with a male chimpanzee named Kendall. Whenever she visited the chimps, Kendall would gently take her hands and inspect her fingernails. Let’s imagine, for the purpose of this essay, that the following statement is true: An AI writes a novel.

Let’s imagine, for the purpose of this essay, that the following statement is true: An AI writes a novel. The road to hell might be paved with good intentions, but the roads to pretty much everywhere else are paved with the corpses of animals. In Crossings, environmental journalist Ben Goldfarb explores the outsized yet underappreciated impacts of the, by one estimate, 65 million kilometres of roads that hold the planet in a paved stranglehold. These extend beyond roadkill to numerous other insidious biological effects. The relatively young discipline of road ecology tries to gauge and mitigate them and sees biologists join forces with engineers and roadbuilders. This is a wide-ranging and eye-opening survey of the situation in the USA and various other countries.

The road to hell might be paved with good intentions, but the roads to pretty much everywhere else are paved with the corpses of animals. In Crossings, environmental journalist Ben Goldfarb explores the outsized yet underappreciated impacts of the, by one estimate, 65 million kilometres of roads that hold the planet in a paved stranglehold. These extend beyond roadkill to numerous other insidious biological effects. The relatively young discipline of road ecology tries to gauge and mitigate them and sees biologists join forces with engineers and roadbuilders. This is a wide-ranging and eye-opening survey of the situation in the USA and various other countries. F

F

University administrators faced with the challenge of responding to the various (and opposed) constituencies invested in the Hamas-Israel war have come up with a number of strategies.

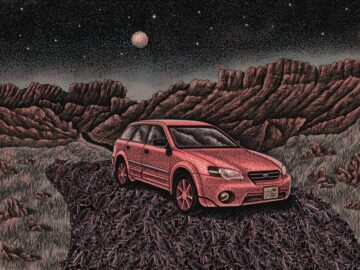

University administrators faced with the challenge of responding to the various (and opposed) constituencies invested in the Hamas-Israel war have come up with a number of strategies. At twenty-six, in 2006, the year before the iPhone launched, I found myself driving a red Subaru Outback—the color was technically “claret metallic,” the friend who’d lent me the car had told me, in case I ever wanted to touch up the paint—on Highway 12 in Utah. I was heading to the East Bay after a painful breakup in New York. I remember, wrongly, that I was listening to a book on tape, a work by a prominent linguist, as I moved through the alien landscape, jagged formations of red rock towering against a cloudless sky.

At twenty-six, in 2006, the year before the iPhone launched, I found myself driving a red Subaru Outback—the color was technically “claret metallic,” the friend who’d lent me the car had told me, in case I ever wanted to touch up the paint—on Highway 12 in Utah. I was heading to the East Bay after a painful breakup in New York. I remember, wrongly, that I was listening to a book on tape, a work by a prominent linguist, as I moved through the alien landscape, jagged formations of red rock towering against a cloudless sky.

Ignacio Silva Neira in Phenomenal World:

Ignacio Silva Neira in Phenomenal World: T

T