Category: Archives

Tuesday Poem

The Creation Story

I’m not afraid of love

or its consequence of light.

It’s not easy to say this

or anything when my entrails

dangle between paradise

and fear.

I am ashamed

I never had the words

to carry a friend from her death

to the stars

correctly.

Or the words to keep

my people safe

from drought

or gunshot.

The stars who were created by words

are circling over this house

formed of calcium, of blood

this house

in danger of being torn apart

by stones of fear.

If these words can do anything

if these songs can do anything

I say bless this house

with stars.

Transfix us with love.

by Joy Harjo

from How we Became Human

W.W. Norton & Company, 2002

David Byrne Isn’t Himself. Or Any Self, Really

David Marchese in The New York Times:

Every year is probably an interesting one for an artist as restless and inquisitive as David Byrne, but I’m willing to bet that 2023 was especially so. In September, a newly restored edition of “Stop Making Sense,” the landmark 1984 concert film by Byrne’s former band, Talking Heads, returned to theaters to much (richly deserved) ballyhoo. Before that, “Here Lies Love,” a musical based on the life of the former Philippine first lady Imelda Marcos, began a five-month run on Broadway. That show featured lyrics by Byrne and music written by him and Fatboy Slim, and was staged in such a way that a regular old theater was transformed into a shape-shifting disco. The film is a rock concert as joyous celebration of community; the musical a seductive portrait of power’s distorting effects. “Rather than be told this is what the world can be like,’’ says Byrne, 71, about his work, “it’s kind of like, ‘We’re going to show to you how things could be.’ ”

Every year is probably an interesting one for an artist as restless and inquisitive as David Byrne, but I’m willing to bet that 2023 was especially so. In September, a newly restored edition of “Stop Making Sense,” the landmark 1984 concert film by Byrne’s former band, Talking Heads, returned to theaters to much (richly deserved) ballyhoo. Before that, “Here Lies Love,” a musical based on the life of the former Philippine first lady Imelda Marcos, began a five-month run on Broadway. That show featured lyrics by Byrne and music written by him and Fatboy Slim, and was staged in such a way that a regular old theater was transformed into a shape-shifting disco. The film is a rock concert as joyous celebration of community; the musical a seductive portrait of power’s distorting effects. “Rather than be told this is what the world can be like,’’ says Byrne, 71, about his work, “it’s kind of like, ‘We’re going to show to you how things could be.’ ”

It was a little surprising to me to see how strong the enthusiasm still is for “Stop Making Sense.” People really have an emotional connection to that film. But do you? What do you feel when you watch it?

It’s almost as if I’m watching a character. I’m a little removed. I retain elements of that person but not all of him. It’s like, Oh, what is the connection between me and that being that I’m looking at?

More here.

What are farm animals thinking?

David Grimm in Science:

DUMMERSTORF, GERMANY—You’d never mistake a goat for a dog, but on an unseasonably warm afternoon in early September, I almost do. I’m in a red-brick barn in northern Germany, trying to keep my sanity amid some of the most unholy noises I’ve ever heard. Sixty Nigerian dwarf goats are taking turns crashing their horns against wooden stalls while unleashing a cacophony of bleats, groans, and retching wails that make it nearly impossible to hold a conversation. Then, amid the chaos, something remarkable happens. One of the animals raises her head over her enclosure and gazes pensively at me, her widely spaced eyes and odd, rectangular pupils seeking to make contact—and perhaps even connection.

DUMMERSTORF, GERMANY—You’d never mistake a goat for a dog, but on an unseasonably warm afternoon in early September, I almost do. I’m in a red-brick barn in northern Germany, trying to keep my sanity amid some of the most unholy noises I’ve ever heard. Sixty Nigerian dwarf goats are taking turns crashing their horns against wooden stalls while unleashing a cacophony of bleats, groans, and retching wails that make it nearly impossible to hold a conversation. Then, amid the chaos, something remarkable happens. One of the animals raises her head over her enclosure and gazes pensively at me, her widely spaced eyes and odd, rectangular pupils seeking to make contact—and perhaps even connection.

It’s a look we see in other humans, in our pets, and in our primate relatives. But not in animals raised for food. Or maybe we just haven’t been looking hard enough.

That’s the core idea here at the Research Institute for Farm Animal Biology (FBN), one of the world’s leading centers for investigating the minds of goats, pigs, and other livestock. On a campus that looks like a cross between a farm and a small research institute—with low-rise buildings nestled among pastures, stables, and the occasional dung pile—scientists are probing the mental and emotional lives of animals we’ve lived with for thousands of years, yet, from a cognitive perspective, know almost nothing about.

More here.

Sunday, December 10, 2023

After Melville

Andrew Schenker in The Baffler:

Writing in 2005, Andrew Delbanco observed, in his critical biography Melville: His World and Work, that the author of Moby-Dick “seems to renew himself for each new generation.” Since the mid-twentieth century, Delbanco notes, “there has been a steady stream of new Melvilles, all of whom seem somehow able to keep up with the preoccupations of the moment.” He lists a few:

Writing in 2005, Andrew Delbanco observed, in his critical biography Melville: His World and Work, that the author of Moby-Dick “seems to renew himself for each new generation.” Since the mid-twentieth century, Delbanco notes, “there has been a steady stream of new Melvilles, all of whom seem somehow able to keep up with the preoccupations of the moment.” He lists a few:

myth-and-symbol Melville

countercultural Melville

anti-war Melville

environmentalist Melville

gay or bisexual Melville

multicultural Melville

global Melville

And then there’s his deathless creation, Ahab, the man who, per Elizabeth Hardwick, “has no ancestor in literature other than all of literature.” Inspired in part, Delbanco speculates, by former vice president and staunch slavery defender John C. Calhoun, the Pequod’s monomaniacal commander has been likened to everyone from Hitler to the nuclear scientists responsible for the atomic bomb to, inevitably, Donald Trump. (Unless, in a reading popular in right-wing media, Trump is actually the white whale and the Democrats who impeached him are Ahab.)

More here.

A Philosophy For The Science Of Animal Consciousness

Leon Vlieger at The Inquisitive Biologist:

The nature of consciousness is one of the hardest problems in biology. What exactly is it? Where did it come from? And are non-human animals conscious? Philosophers and scientists range from ascribing consciousness to all life (biopsychism), or even all matter (panpsychism), to attributing it exclusively to humans. Seemingly beyond the purview of empirical science due to its subjective nature, there is a lack of “intuitively attractive solutions” (p. xiii). In the opinion of Walter Veit, an assistant professor in philosophy, that just will not do. In this slim but advanced-level book, he outlines a mightily interesting thesis of how consciousness could have gradually evolved, which aspect of it likely appeared first, and why we urgently need to step away from taking human consciousness as our yardstick.

The nature of consciousness is one of the hardest problems in biology. What exactly is it? Where did it come from? And are non-human animals conscious? Philosophers and scientists range from ascribing consciousness to all life (biopsychism), or even all matter (panpsychism), to attributing it exclusively to humans. Seemingly beyond the purview of empirical science due to its subjective nature, there is a lack of “intuitively attractive solutions” (p. xiii). In the opinion of Walter Veit, an assistant professor in philosophy, that just will not do. In this slim but advanced-level book, he outlines a mightily interesting thesis of how consciousness could have gradually evolved, which aspect of it likely appeared first, and why we urgently need to step away from taking human consciousness as our yardstick.

More here.

Democracy in the Real World

Thad Williamson in the Boston Review:

Danielle Allen’s Justice by Means of Democracy represents a major, and much-needed, shift in perspective. In the book, she locates the work of establishing justice not in the philosophy seminar room but in real-world discussions with diverse, everyday people: “talking with strangers” with intention to co-create a more democratic and more just society together. Fifty years on from Rawls’s foundational A Theory of Justice, Allen has set out to articulate not simply a new theory of justice but a new way of thinking about justice: one that trades Rawls’s abstract thought experiments for real-life ones. And equally importantly, it offers us the concrete tools for getting from thinking about to practicing democracy, however imperfectly, in messy situations in which the needs and future prospects of real people are concretely implicated.

Danielle Allen’s Justice by Means of Democracy represents a major, and much-needed, shift in perspective. In the book, she locates the work of establishing justice not in the philosophy seminar room but in real-world discussions with diverse, everyday people: “talking with strangers” with intention to co-create a more democratic and more just society together. Fifty years on from Rawls’s foundational A Theory of Justice, Allen has set out to articulate not simply a new theory of justice but a new way of thinking about justice: one that trades Rawls’s abstract thought experiments for real-life ones. And equally importantly, it offers us the concrete tools for getting from thinking about to practicing democracy, however imperfectly, in messy situations in which the needs and future prospects of real people are concretely implicated.

More here.

The Mystery of Beethoven’s “Immortal Beloved”

Emily Zarevich at JSTOR Daily:

It’s one of the great mysteries of music history, as high in the ranks as “Who wrote the Renaissance lover’s tribute ‘Greensleeves’” and “How did Amadeus Mozart really die?” In eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Europe, correspondence was a private means of communication, and some clandestine love affairs conducted in secret succeeded in evading confirmation from even the most determined detectives. Which is why the world is still wondering, centuries after the question was first asked, “Who was Beethoven’s ‘Immortal Beloved?’”

It’s one of the great mysteries of music history, as high in the ranks as “Who wrote the Renaissance lover’s tribute ‘Greensleeves’” and “How did Amadeus Mozart really die?” In eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Europe, correspondence was a private means of communication, and some clandestine love affairs conducted in secret succeeded in evading confirmation from even the most determined detectives. Which is why the world is still wondering, centuries after the question was first asked, “Who was Beethoven’s ‘Immortal Beloved?’”

More here.

Denny Laine (1944 – 2023) Musician, Founder of Moody Blues and Wings

Jane Wodening (1936 – 2023) Artist

Ryan O’Neal (1941 – 2023) Actor

Sunday Poem

The Bostonian Reading Amichai

In our house, no one was taught

to argue with God. So how could I

disbelieve my nightlight, resist

my pink-and-blue picture books,

or the dove on top of the Christmas tree?

All the glistening meats and cakes

might vaporize, and bedtime stories

unwrite themselves, give over

to bad dreams. I never knew

there was a tradition of despair

in other households, or any need

for salvation. Nothing exact

ever called to me. Even now,

bewildered by the state of the world,

of my life, I don’t rage

as other women do. Neither

do I have their faith. I don’t argue

with God how none of it makes sense.

That’s simply how it is—

like the original blur at the edge of light

the nightlight casts.

by Pamela Stewart

from Infrequent Mysteries

Alice James Books 1991

Hipster coffee enthusiasts have taken the joy out of coffee

Joy Saha in Salon:

Coffee is multifunctional: For some, like me, it’s a morning necessity. For others, it’s a once in a while indulgence. And for a select few, it’s a sugary treat — something that’s more akin to dessert than mandatory fuel.

Coffee is multifunctional: For some, like me, it’s a morning necessity. For others, it’s a once in a while indulgence. And for a select few, it’s a sugary treat — something that’s more akin to dessert than mandatory fuel.

Regardless of what purpose coffee serves for you, the beverage is at its crux pleasurable. There’s nothing like stopping by at your local coffee shop, grabbing a beverage and reveling in that first sip. In a world where global atrocities continue to make headlines and the onset of another debilitating pandemic doesn’t seem like a far-fetched concept, coffee provides a bit of a reprieve.

That, however, has been tainted by hipster cafes: swanky spots with fancy barista gadgets, beans sourced from an array of exclusive locations (like coffee excreted from civet cats found on the islands of Bali!), and a menu that’s shorter than my weekly grocery list. If the unconventional coffee isn’t enough to grab your attention, the eye-catching aesthetic certainly will. Such cafes are either riddled with minimalistic decor or filled with a superfluous amount of plants and wacky artwork.

More here.

“There’s Nothing Mystical About the Idea that Ideas Change History”

Matt Johnson in Quillette:

Quillette: In Enlightenment Now, you discuss the importance of “norms and institutions that channel parochial interests into universal benefits.” Jonathan Haidt says the nation is the largest unit that activates the tribal mind, whereas Peter Singer says we are on an “escalator of reason” that allows our circle of moral concern to keep expanding. What would you say are the limits of human solidarity?

Quillette: In Enlightenment Now, you discuss the importance of “norms and institutions that channel parochial interests into universal benefits.” Jonathan Haidt says the nation is the largest unit that activates the tribal mind, whereas Peter Singer says we are on an “escalator of reason” that allows our circle of moral concern to keep expanding. What would you say are the limits of human solidarity?

Steven Pinker: I agree that the moral imperative to treat all lives as equally valuable has to pull outward against our natural tendency to favor kin, clan, and tribe. So we may never see the day when people’s primary loyalty will be to all of Homo sapiens, let alone all sentient beings. But it’s not clear that the nation-state, which is a historical construction, is the most natural resting place for Singer’s expanding circle. The United States, in particular, was consecrated by a social contract rather than as an ethnostate, and it seems to command a lot of patriotism.

And while there surely is a centripetal force of tribalism, there are two forces pushing outward against it. One is the moral fact that it’s awkward, to say the least, to insist that some lives are more valuable than others, particularly when you’re face-to-face with those others. The other is the pragmatic fact that our fate is increasingly aligned with that of the rest of the planet. Some of our parochial priorities can only be solved at a global scale, like climate, trade, piracy, terrorism, and cybercrime. As the world becomes more interconnected, which is inexorable, our interests become more tied up with those in the rest of the world. That will push in the same direction as the moral concern for universal human welfare.

More here.

Saturday, December 9, 2023

Becoming Ella Fitzgerald

Chris Vognar at the LA Times:

The title of “Becoming Ella Fitzgerald,” Judith Tick’s incisive, doggedly researched new biography of the 20th century’s preeminent songstress, suggests action and movement. This is no accident. As Tick writes, “across her entire career, the artist was always ‘becoming Ella Fitzgerald.’”

The title of “Becoming Ella Fitzgerald,” Judith Tick’s incisive, doggedly researched new biography of the 20th century’s preeminent songstress, suggests action and movement. This is no accident. As Tick writes, “across her entire career, the artist was always ‘becoming Ella Fitzgerald.’”

Her reign began as a swing singer with the great bandleader and drummer Chick Webb; took on a bop tenor as she fell under the influence of Dizzy Gillespie; and blossomed into refined pop elegance with her remarkable run of songbook albums produced by Norman Granz. She could irk the jazz purists and confound the supper club set. But for more than 60 years, to paraphrase a male peer who weaves in and out of this narrative, she did it her way. Tick, a professor emerita of music history at Northwestern University, proves an ideal guide to Fitzgerald’s perpetual progress. She translates what she hears with lyrical clarity, describing the “honey-mustard blend” of Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong’s voices on their classic duets.

more here.

“Zero at the Bone,” by Christian Wiman

Alexandra Jacobs at the New York Times:

Much of “Zero at the Bone” is set a long way from Yale: in the hot, flat, scrubby towns of Texas where Wiman grew up, the apparent golden child of a deeply tarnished family, “my father vanishing, my mother wracked with rage and faith, my siblings sinking into drugs and alcohol, my own mind burning at night like an oil fire on water.” (He mentions only briefly an opiate addiction of his own, and spends maybe a little too much time recapping an abandoned bildungsroman in service of the theory that God is a failed novelist “who seems conflicted about how — or whether — to finish us.”)

Much of “Zero at the Bone” is set a long way from Yale: in the hot, flat, scrubby towns of Texas where Wiman grew up, the apparent golden child of a deeply tarnished family, “my father vanishing, my mother wracked with rage and faith, my siblings sinking into drugs and alcohol, my own mind burning at night like an oil fire on water.” (He mentions only briefly an opiate addiction of his own, and spends maybe a little too much time recapping an abandoned bildungsroman in service of the theory that God is a failed novelist “who seems conflicted about how — or whether — to finish us.”)

Along with humanity’s end in the main, Wiman has been forced to confront his own end in the particular. His refusal to submit to America’s “cancer camaraderie,” instead trying to explain the “otherworldly intimacy” of its pain, reminded me of Barbara Ehrenreich. “Through the rooms/the white minders come and go/with their upbeat and their bags of blood,” he writes Prufrockishly of hospital treatment.

more here.

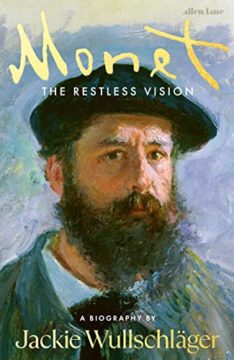

Monet: Painting Is Terribly Difficult

Julian Barnes at the LRB:

In seventeen years it will be the 200th anniversary of Monet’s birth, yet he might still be the best way to introduce someone young to art – and not just modern art. This is partly because of what he didn’t paint. He didn’t do historical or religious subjects: no need to know what is happening at the Annunciation (let alone the Assumption of the Virgin) or what Oedipus said to the Sphinx or why so many naked women are attending the death of Sardanapalus. He never painted a literary scene for which you need to know the story. None of his paintings refers to an earlier painting. He was the first great artist since the Renaissance never to paint a nude. He painted portraits but it didn’t matter (except to him) whom they were of. You don’t need to know the history of art to appreciate a Monet picture because he wasn’t much interested in the history of art himself (though he revered Watteau and Delacroix and Velázquez). He had even less interest in the science of visual perception. His art was secular and apolitical.

In seventeen years it will be the 200th anniversary of Monet’s birth, yet he might still be the best way to introduce someone young to art – and not just modern art. This is partly because of what he didn’t paint. He didn’t do historical or religious subjects: no need to know what is happening at the Annunciation (let alone the Assumption of the Virgin) or what Oedipus said to the Sphinx or why so many naked women are attending the death of Sardanapalus. He never painted a literary scene for which you need to know the story. None of his paintings refers to an earlier painting. He was the first great artist since the Renaissance never to paint a nude. He painted portraits but it didn’t matter (except to him) whom they were of. You don’t need to know the history of art to appreciate a Monet picture because he wasn’t much interested in the history of art himself (though he revered Watteau and Delacroix and Velázquez). He had even less interest in the science of visual perception. His art was secular and apolitical.

more here.

Saturday Poem

Garter Snake

The stately ripple of a garter snake

in sinuous procession through the grass

compelled my eye. It stopped and held its head

high above the lawn, and the delicate curve

of its slender body formed the letter S—

for “serpent,” I presume, as though

diminutive majesty obliged embodiment.

The garter snake reminded me of those

cartouches where the figure of a snake

seems to suggest the presence of a god,

until more flickering than any god

the small snake gathered glidingly and slid,

but with such cadence to its rapt advance

that when it stopped once more to raise its head

it was stiller than the stillest mineral,

and when it moved again it moved the way

a curl of water slips along a stone

or like the ardent progress of a tear

till deeper still it gave the rubbled grass

and the dull hollows where its ripples ran

lithe scintillas of exuberance,

moving the way a chance felicity

silvers the whole attention of the mind.

by Eric Ormsby

from For a Modest God

Grove Press, 1997

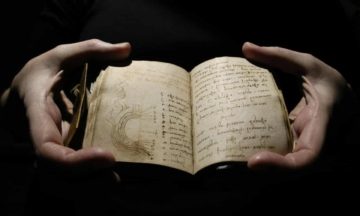

The Notebook by Roland Allen – notes on living

Sukhdev Sandhu in The Guardian:

Roland Allen loves notebooks. Why wouldn’t he? He is, after all, a writer. In his new study, delightfully subtitled A History of Thinking on Paper, he declares: “If your business is words, a notebook can be at once your medium – and your mirror.” Paul Valéry was at least as devoted to his notebooks as the symbolist poetry for which he is best known. He awoke early each morning for half a century to write in them, amassing 261 books in total. “Having dedicated those hours to the life of the mind, I earn the right to be stupid for the rest of the day.”

Roland Allen loves notebooks. Why wouldn’t he? He is, after all, a writer. In his new study, delightfully subtitled A History of Thinking on Paper, he declares: “If your business is words, a notebook can be at once your medium – and your mirror.” Paul Valéry was at least as devoted to his notebooks as the symbolist poetry for which he is best known. He awoke early each morning for half a century to write in them, amassing 261 books in total. “Having dedicated those hours to the life of the mind, I earn the right to be stupid for the rest of the day.”

Notebooks in different guises have been around since at least the late 13th century. In Florence they were used as ledgers, spurred the development of double-entry book-keeping, and, not least because they were made of paper rather than more expensive and less stable parchment, were integral to the rise of mercantilism. In the form of sketch books they allowed artists to depict their surroundings repeatedly and develop more realistic techniques.

More here.

The Year A.I. Ate the Internet

Sue Halpern in The New Yorker:

A little more than a year ago, the world seemed to wake up to the promise and dangers of artificial intelligence when OpenAI released ChatGPT, an application that enables users to converse with a computer in a singularly human way. Within five days, the chatbot had a million users. Within two months, it was logging a hundred million monthly users—a number that has now nearly doubled. Call this the year many of us learned to communicate, create, cheat, and collaborate with robots.

A little more than a year ago, the world seemed to wake up to the promise and dangers of artificial intelligence when OpenAI released ChatGPT, an application that enables users to converse with a computer in a singularly human way. Within five days, the chatbot had a million users. Within two months, it was logging a hundred million monthly users—a number that has now nearly doubled. Call this the year many of us learned to communicate, create, cheat, and collaborate with robots.

Shortly after ChatGPT came out, Google released its own chatbot, Bard; Microsoft incorporated OpenAI’s model into its Bing search engine; Meta débuted LLaMA; and Anthropic came out with Claude, a “next generation AI assistant for your tasks, no matter the scale.” Suddenly, the Internet seemed nearly animate. It wasn’t that A.I. itself was new: indeed, artificial intelligence has become such a routine part of our lives that we hardly recognize it when a Netflix algorithm recommends a film, a credit-card company automatically detects fraudulent activity, or Amazon’s Alexa delivers a summary of the morning’s news.

But, while those A.I.s work in the background, often in a scripted and brittle way, chatbots are responsive and improvisational. They are also unpredictable. When we ask for their assistance, prompting them with queries about things we don’t know, or asking them for creative help, they often generate things that did not exist before, seemingly out of thin air. Poems, literature reviews, essays, research papers, and three-act plays are delivered in plain, unmistakably human language. It’s as if the god in the machine had been made in our image.

More here.