Ashley Gardini at JSTOR:

Recognizing the work of Denise Scott Brown is necessary for understanding American architecture in the second half of the twentieth century. Scott Brown is an architect and urban planner who wrote, spoke, taught, and designed over the course of her career, creating a lasting influence on both the built environment and future generations of architects. Yet, when we think of her, the history highlighted is often the injustices she experienced as a woman working in the architectural field. Why? Because Scott Brown actually spoke about it. She’s used her position to highlight the professional difficulties she faced because of her gender and because of her role as “the wife.”

Scott Brown was born in Nikana, Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia) in 1931. She studied architecture on three continents—Africa, Europe, and North America—before settling in Philadelphia.

more here.

“By the way, how are you managing with the 100-copy collection?”

“By the way, how are you managing with the 100-copy collection?” 2023 will be the year with the highest emissions ever recorded, according to new projections from the

2023 will be the year with the highest emissions ever recorded, according to new projections from the  Donald Trump is an astoundingly dangerous candidate for president. He is a pathological liar, with clear authoritarian instincts. Were he elected to a second term, the damage he would do to the institutions of our republic is profound. His reelection would be worse than any political event in the history of America — save the decision of South Carolina to launch the Civil War.

Donald Trump is an astoundingly dangerous candidate for president. He is a pathological liar, with clear authoritarian instincts. Were he elected to a second term, the damage he would do to the institutions of our republic is profound. His reelection would be worse than any political event in the history of America — save the decision of South Carolina to launch the Civil War. I remember where I was when Edward Said died.

I remember where I was when Edward Said died.

Exactly. I love to point out philosophical mistakes made by those scientists who think philosophy is a throwaway. In the areas of science that I am interested in—the nature of consciousness, the nature of reality, the nature of explanation—they often fall into the old traps that philosophers have learned about by falling into those traps themselves. There is no learning without making mistakes, but then you have to learn from your mistakes.

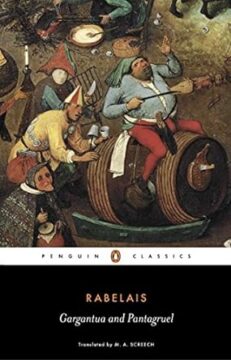

Exactly. I love to point out philosophical mistakes made by those scientists who think philosophy is a throwaway. In the areas of science that I am interested in—the nature of consciousness, the nature of reality, the nature of explanation—they often fall into the old traps that philosophers have learned about by falling into those traps themselves. There is no learning without making mistakes, but then you have to learn from your mistakes. To try to understand the whole of Rabelais or his writing is the work of a lifetime—I am not sure if Rabelais himself would think such a lifetime well spent—but even a passing acquaintance with this odd fellow is certainly worthwhile. There is a mystery here, of the finest vintage; every time I pick up the blue brick called Gargantua and Pantagruel, I find myself asking, in the midst of chuckles, how can something so stupid have turned literature upside down? Why does this book matter at all?

To try to understand the whole of Rabelais or his writing is the work of a lifetime—I am not sure if Rabelais himself would think such a lifetime well spent—but even a passing acquaintance with this odd fellow is certainly worthwhile. There is a mystery here, of the finest vintage; every time I pick up the blue brick called Gargantua and Pantagruel, I find myself asking, in the midst of chuckles, how can something so stupid have turned literature upside down? Why does this book matter at all?  When Luana Marques was growing up in Brazil, life was not easy. Her parents had her when they were very young, and they didn’t know how to take care of themselves, much less their children. Drugs and alcohol were also a problem. “Between the many instances of domestic violence, I often felt scared, wondering when something bad would happen next,” she says. She lived

When Luana Marques was growing up in Brazil, life was not easy. Her parents had her when they were very young, and they didn’t know how to take care of themselves, much less their children. Drugs and alcohol were also a problem. “Between the many instances of domestic violence, I often felt scared, wondering when something bad would happen next,” she says. She lived  Obesity plays out as a private struggle and a public health crisis. In the United States, about 70% of adults are affected by excess weight, and in Europe that number is more than half. The stigma against fat can be crushing; its risks, life-threatening. Defined as a body mass index of at least 30, obesity is thought to power type 2 diabetes, heart disease, arthritis, fatty liver disease, and certain cancers. Yet drug treatments for obesity have a sorry past, one often intertwined with social pressure to lose weight and the widespread belief that excess weight reflects weak willpower. From “rainbow diet pills” packed with amphetamines and diuretics that were marketed to women beginning in the 1940s, to the 1990s rise and fall of fen-phen, which triggered catastrophic heart and lung conditions, history is beset by failures to find safe, successful weight loss drugs.

Obesity plays out as a private struggle and a public health crisis. In the United States, about 70% of adults are affected by excess weight, and in Europe that number is more than half. The stigma against fat can be crushing; its risks, life-threatening. Defined as a body mass index of at least 30, obesity is thought to power type 2 diabetes, heart disease, arthritis, fatty liver disease, and certain cancers. Yet drug treatments for obesity have a sorry past, one often intertwined with social pressure to lose weight and the widespread belief that excess weight reflects weak willpower. From “rainbow diet pills” packed with amphetamines and diuretics that were marketed to women beginning in the 1940s, to the 1990s rise and fall of fen-phen, which triggered catastrophic heart and lung conditions, history is beset by failures to find safe, successful weight loss drugs.

Will we ever truly understand the Neanderthals? Archaeologist Ludovic Slimak paints a vivid picture in The Naked Neanderthal. Written like a philosophical travelogue, this intriguing book offers personal vignettes of archaeological excavations and provocative critiques of researchers’ tendencies to interpret Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis) as the intellectual and creative cousins of Homo sapiens. Instead, the author argues, they are stranger to us than people might admit, with a culture that is both sophisticated and alien.

Will we ever truly understand the Neanderthals? Archaeologist Ludovic Slimak paints a vivid picture in The Naked Neanderthal. Written like a philosophical travelogue, this intriguing book offers personal vignettes of archaeological excavations and provocative critiques of researchers’ tendencies to interpret Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis) as the intellectual and creative cousins of Homo sapiens. Instead, the author argues, they are stranger to us than people might admit, with a culture that is both sophisticated and alien. We are living in an age of tech backlash. Especially given the perceived effects of social media on the outcome, the 2016 election undoubtedly catalyzed much of the critical sentiment about the role technology plays in our private lives and in society at large. This backlash can be attributed to a shift in thinking neatly expressed by the title of sociologist Zeynep Tufekci’s 2018 essay for MIT Technology Review, “How Social Media Took Us From Tahrir Square to Donald Trump.” The same technologies that, circa 2010, were expected to herald a golden age of democracy were, by 2018, more likely to be framed as authoritarian tools and threats to democracy. Around the same time, less rapt voices also gained traction in debates about the relative merits not only of social media but of smartphones, the Internet, algorithmic governance, automation, self-driving cars, and, most recently, artificial intelligence. While it is not obvious to me that this critical sentiment has amounted to a reconfiguration of how our society relates to technology, it nevertheless seems clear that our collective technoenthusiasm has been dialed down a few notches.

We are living in an age of tech backlash. Especially given the perceived effects of social media on the outcome, the 2016 election undoubtedly catalyzed much of the critical sentiment about the role technology plays in our private lives and in society at large. This backlash can be attributed to a shift in thinking neatly expressed by the title of sociologist Zeynep Tufekci’s 2018 essay for MIT Technology Review, “How Social Media Took Us From Tahrir Square to Donald Trump.” The same technologies that, circa 2010, were expected to herald a golden age of democracy were, by 2018, more likely to be framed as authoritarian tools and threats to democracy. Around the same time, less rapt voices also gained traction in debates about the relative merits not only of social media but of smartphones, the Internet, algorithmic governance, automation, self-driving cars, and, most recently, artificial intelligence. While it is not obvious to me that this critical sentiment has amounted to a reconfiguration of how our society relates to technology, it nevertheless seems clear that our collective technoenthusiasm has been dialed down a few notches. A monkey in the zoo, defiantly

A monkey in the zoo, defiantly