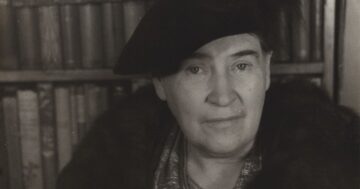

Anne Matthews in The American Scholar:

Willa Cather loathed biographers, professors, and autograph fiends. After her war novel, One of Ours, won the Pulitzer in 1923, she decided to cull the herd. “This is not a case for the Federal Bureau of Investigation,” she told one researcher. Burn my letters and manuscripts, she begged her friends. Hollywood filmed a loose adaptation of A Lost Lady, starring Barbara Stanwyck, in 1934, and Cather soon forbade any further screen, radio, and television versions of her work. No direct quotations from surviving correspondence, she ordered libraries, and for decades a family trust enforced her commands.

Willa Cather loathed biographers, professors, and autograph fiends. After her war novel, One of Ours, won the Pulitzer in 1923, she decided to cull the herd. “This is not a case for the Federal Bureau of Investigation,” she told one researcher. Burn my letters and manuscripts, she begged her friends. Hollywood filmed a loose adaptation of A Lost Lady, starring Barbara Stanwyck, in 1934, and Cather soon forbade any further screen, radio, and television versions of her work. No direct quotations from surviving correspondence, she ordered libraries, and for decades a family trust enforced her commands.

Archival scholars managed to undermine what her major biographer James Woodress called “the traps, pitfalls and barricades she placed in the biographer’s path,” even as literary critics reveled in trench warfare over Cather’s sexuality. In 2018, her letters finally entered the public domain, allowing Benjamin Taylor to create the first post-ban life of Cather for general readers.

Chasing Bright Medusas is timed for the 150th anniversary of Cather’s birth in Virginia. The title alludes to her 1920 story collection on art’s perils, Youth and the Bright Medusa. (“It is strange to come at last to write with calm enjoyment,” she told a college friend. “But Lord—what a lot of life one uses up chasing ‘bright Medusas,’ doesn’t one?”) Soon she urged modern writers to toss the furniture of naturalism out the window, making room for atmosphere and emotion. What she wanted was the unfurnished novel, or “novel démeublé,” as she called it in a 1922 essay. Paraphrasing Dumas, she posited that “to make a drama, all you need is one passion, and four walls.”

More here.