Joelle M. Abi-Rached in Boston Review:

The face of the ongoing onslaught on Gaza has no doubt been Dr. Hammam Alloh, the thirty-six-year-old Palestinian nephrologist at northern Gaza’s Al-Shifa Hospital who refused to evacuate it when it was invaded by Israeli troops. “And if I go, who treats my patients?” he said in an October 31 interview. “We are not animals. We have the right to receive proper healthcare,” he added. Two weeks later, Alloh was killed by an Israeli airstrike, along with his father, brother-in-law, and father-in-law.

Alloh’s use of the word “animals” was certainly not lost on viewers. Israeli Defense Minister Yoav Gallant had used that same language on October 9 when he announced a “complete siege” on Gaza, labeling its residents as “human animals.” Hamas’s attacks on October 7 would predictably generate a violent military reaction from Israel. But this Israeli campaign in Gaza, a strip of land where more than 80 percent of its population lived in poverty even before October 7, has been of a different character entirely than any previous ones. This onslaught has featured direct attacks on hospitals and the intentional undermining of the entire health care system: shelling, the killing and arresting of health care personnel, the direct and indirect killing of hundreds of patients, underprovision or complete lack of proper medical care, and unwarranted suffering for thousands of patients due to shortages in basic medications, water, food, and fuel. The attacks have made clear that the repression of Palestinian rights now has a new feature: the systematic destruction of the very institutions that sustain life.

More here.

Maria Haro Sly in Phenomenal World:

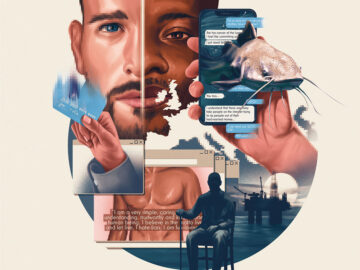

Maria Haro Sly in Phenomenal World: Around five years ago, David—a pseudonym—realized that he was fighting with his girlfriend all the time. On their first date, he had told her that he hoped to have sex with a thousand women before he died. They’d eventually agreed to have an exclusive relationship, but monogamy remained a source of tension. “I always used to tell her how much it bothered me,” he recalled. “I was an asshole.” An Israeli man now in his mid-thirties, David felt conflicted about other life issues. Did he want kids? How much should he prioritize making money? In his twenties, he’d tried psychotherapy several times; he would see a therapist for a few months, grow frustrated, stop, then repeat the cycle. He developed a theory. The therapists he saw wanted to help him become better adjusted given his current world view—but perhaps his world view was wrong. He wanted to examine how defensible his values were in the first place.

Around five years ago, David—a pseudonym—realized that he was fighting with his girlfriend all the time. On their first date, he had told her that he hoped to have sex with a thousand women before he died. They’d eventually agreed to have an exclusive relationship, but monogamy remained a source of tension. “I always used to tell her how much it bothered me,” he recalled. “I was an asshole.” An Israeli man now in his mid-thirties, David felt conflicted about other life issues. Did he want kids? How much should he prioritize making money? In his twenties, he’d tried psychotherapy several times; he would see a therapist for a few months, grow frustrated, stop, then repeat the cycle. He developed a theory. The therapists he saw wanted to help him become better adjusted given his current world view—but perhaps his world view was wrong. He wanted to examine how defensible his values were in the first place. The cosmetics entrepreneur Helena Rubinstein once observed, “There are no ugly women, only lazy ones.” The kind of beauty she had in mind is an ambivalent gift. On the one hand, it is not confined to the biologically blessed but available to everyone; on the other, it is a hard-earned prize, a product of ritualistic and often painstaking devotions at the mirror. Is this sort of beauty worth pursuing? Some feminist thinkers have bashed it as a superficial distraction. “Taught from infancy that beauty is woman’s sceptre, the mind shapes itself to the body, and roaming round its gilt cage, only seeks to adorn its prison,” Mary Wollstonecraft wrote disdainfully in 1792. Yet there is a tinge of misogyny to the familiar accusation that cosmetic projects are fluffy trivialities. Perhaps there is more truth (and more respect) to be found in the view of the novelist Henry James, who once described a female character’s flair for fashion as a form of “genius.”

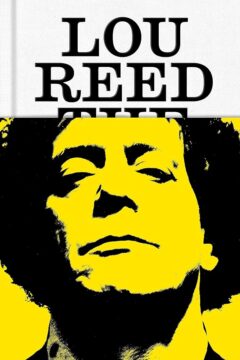

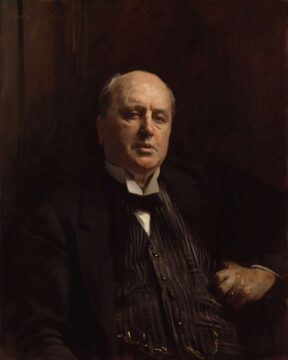

The cosmetics entrepreneur Helena Rubinstein once observed, “There are no ugly women, only lazy ones.” The kind of beauty she had in mind is an ambivalent gift. On the one hand, it is not confined to the biologically blessed but available to everyone; on the other, it is a hard-earned prize, a product of ritualistic and often painstaking devotions at the mirror. Is this sort of beauty worth pursuing? Some feminist thinkers have bashed it as a superficial distraction. “Taught from infancy that beauty is woman’s sceptre, the mind shapes itself to the body, and roaming round its gilt cage, only seeks to adorn its prison,” Mary Wollstonecraft wrote disdainfully in 1792. Yet there is a tinge of misogyny to the familiar accusation that cosmetic projects are fluffy trivialities. Perhaps there is more truth (and more respect) to be found in the view of the novelist Henry James, who once described a female character’s flair for fashion as a form of “genius.” “King of New York” was the epithet given to him by David Bowie, an obsessive Velvets fan who rescued Reed’s lacklustre solo career by producing Transformer, which spawned his biggest hit, Walk on the Wild Side. It’s also the title of Will Hermes’s meticulous yet vivid new biography, the first to draw on the archive donated to the New York Public Library by Reed’s widow Laurie Anderson. As in his 2011 book Love Goes to Buildings on Fire, about the city’s mid-70s musical landscape, Hermes expertly conjures the different scenes Reed inhabited, placing him amid a rich cast of collaborators, friends and lovers.

“King of New York” was the epithet given to him by David Bowie, an obsessive Velvets fan who rescued Reed’s lacklustre solo career by producing Transformer, which spawned his biggest hit, Walk on the Wild Side. It’s also the title of Will Hermes’s meticulous yet vivid new biography, the first to draw on the archive donated to the New York Public Library by Reed’s widow Laurie Anderson. As in his 2011 book Love Goes to Buildings on Fire, about the city’s mid-70s musical landscape, Hermes expertly conjures the different scenes Reed inhabited, placing him amid a rich cast of collaborators, friends and lovers. Forget everything you’ve ever heard about less being more, about economy of syntax, about the read-between-the-lines profundity of wide-margined, double-spaced “spare prose.” To read a paragraph by Henry James — a single one can sprawl across pages — is to luxuriate in linguistic excess.

Forget everything you’ve ever heard about less being more, about economy of syntax, about the read-between-the-lines profundity of wide-margined, double-spaced “spare prose.” To read a paragraph by Henry James — a single one can sprawl across pages — is to luxuriate in linguistic excess. Police officers are often the last to know when someone is being conned. A worried son might spot unusual payments on his elderly father’s bank statement. A concerned friend will do a reverse-image search on a suspiciously good-looking dating-app match. A fraudster will run out of excuses as to why they can’t meet. A horrible realisation will dawn and a report will be filed.

Police officers are often the last to know when someone is being conned. A worried son might spot unusual payments on his elderly father’s bank statement. A concerned friend will do a reverse-image search on a suspiciously good-looking dating-app match. A fraudster will run out of excuses as to why they can’t meet. A horrible realisation will dawn and a report will be filed. Goo. Gunk. Gloop. Gak. By its own definition, slime is hard to grasp. As an object of disgust, it represents our fears and stigmas, the unknown Other. As a toy or sight gag, it’s a silly plaything. It’s easy to forget that slime permeates every living being on Earth, that, like the cosmos or fungi, slime’s existence is vital to our own, a biological imperative as much as oxygen or sunlight. Nebulous and omnipresent, deathless and primordial, slime is an essential link between nonliving matter and the first life that developed in the ocean 3.6 billion years ago. Slime molds are at least millions of years old and can thrive in outer space. The granddaddy of all mankind, slime is everywhere. It’s also easy to miss, which helps explain why we’re often so afraid of it.

Goo. Gunk. Gloop. Gak. By its own definition, slime is hard to grasp. As an object of disgust, it represents our fears and stigmas, the unknown Other. As a toy or sight gag, it’s a silly plaything. It’s easy to forget that slime permeates every living being on Earth, that, like the cosmos or fungi, slime’s existence is vital to our own, a biological imperative as much as oxygen or sunlight. Nebulous and omnipresent, deathless and primordial, slime is an essential link between nonliving matter and the first life that developed in the ocean 3.6 billion years ago. Slime molds are at least millions of years old and can thrive in outer space. The granddaddy of all mankind, slime is everywhere. It’s also easy to miss, which helps explain why we’re often so afraid of it. The past year has given many of us reason to pause.

The past year has given many of us reason to pause.  In the surreal aftermath of my suicide attempt and amid the haze of my own processing, my best friend visited me in the hospital with a (soft-bound and thus mental-patient-safe) copy of David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest under his arm. It was the spring of 2021. A couple months earlier, I had slipped in a tub, suffered a concussion, and triggered my first episode of major depression, and those had been the most difficult months of my life.

In the surreal aftermath of my suicide attempt and amid the haze of my own processing, my best friend visited me in the hospital with a (soft-bound and thus mental-patient-safe) copy of David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest under his arm. It was the spring of 2021. A couple months earlier, I had slipped in a tub, suffered a concussion, and triggered my first episode of major depression, and those had been the most difficult months of my life. The Supreme Court is on a collision course with itself, and it’s not clear that the justices even know it. We are now witnessing a five-car pileup of Trump–slash–Jan. 6 cases that will either be heard by the Supreme Court or land on their white marble steps in the coming weeks. The court has already agreed to hear the case of Joseph Fischer, the former Pennsylvania cop accused of taking part in the Jan. 6 storming of the Capitol and assaulting police officers,

The Supreme Court is on a collision course with itself, and it’s not clear that the justices even know it. We are now witnessing a five-car pileup of Trump–slash–Jan. 6 cases that will either be heard by the Supreme Court or land on their white marble steps in the coming weeks. The court has already agreed to hear the case of Joseph Fischer, the former Pennsylvania cop accused of taking part in the Jan. 6 storming of the Capitol and assaulting police officers,  T

T A well-known tourist attraction in Vanuatu is a large private compound near Port Vila on the island of Efate, belonging to local artist Aloï Pilioko. Situated beside Erakor Lagoon, the property — called Esnaar — was the shared studio home of Pilioko, a migrant from the island of Wallis in French Polynesia, and his French-Russian partner, the late Nicolaï Michoutouchkine, who passed away in 2010. After acquiring the property in 1961, the two artists pursued remarkable careers together, traveling, collecting, exhibiting, and making “Oceanic art” all over the world. In the 1990s, the property was converted into a tourist attraction with outdoor pavilions housing displays of travel memorabilia, a shop where they sold a line of hand-painted clothing, and ethnographic works from the collection distributed around the gardens and on display inside their studio homes.

A well-known tourist attraction in Vanuatu is a large private compound near Port Vila on the island of Efate, belonging to local artist Aloï Pilioko. Situated beside Erakor Lagoon, the property — called Esnaar — was the shared studio home of Pilioko, a migrant from the island of Wallis in French Polynesia, and his French-Russian partner, the late Nicolaï Michoutouchkine, who passed away in 2010. After acquiring the property in 1961, the two artists pursued remarkable careers together, traveling, collecting, exhibiting, and making “Oceanic art” all over the world. In the 1990s, the property was converted into a tourist attraction with outdoor pavilions housing displays of travel memorabilia, a shop where they sold a line of hand-painted clothing, and ethnographic works from the collection distributed around the gardens and on display inside their studio homes.